The document provides an overview of linguistic terminology and concepts, including:

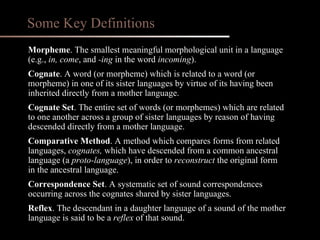

1) It defines basic linguistic terms like nouns, verbs, cases, and discusses language features like grammar.

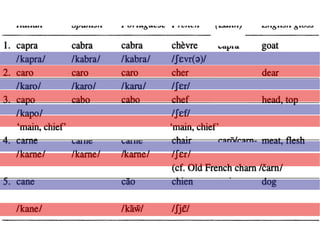

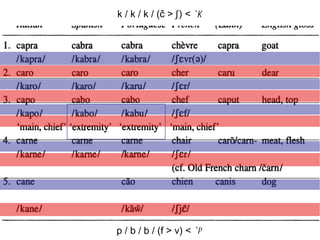

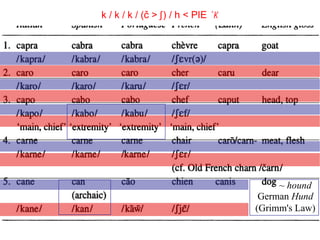

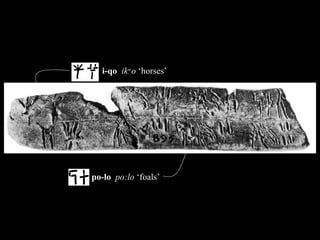

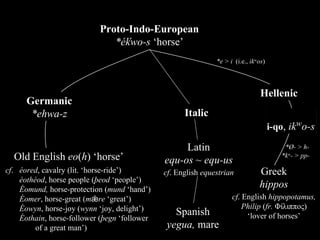

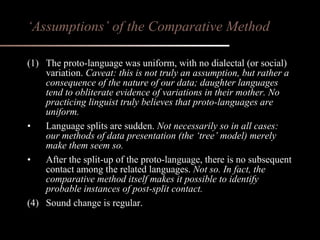

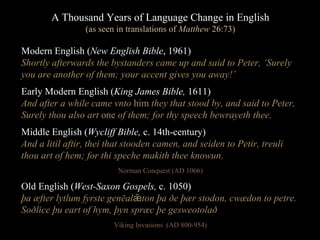

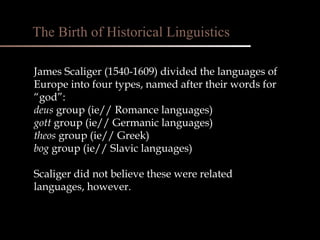

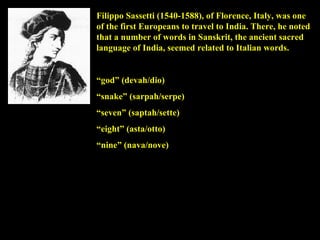

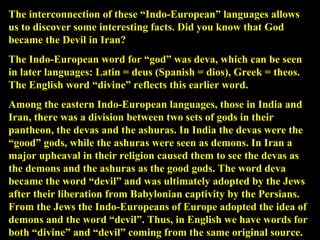

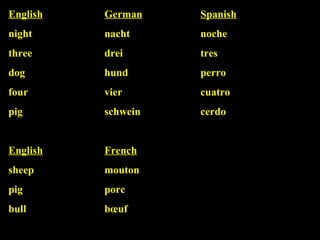

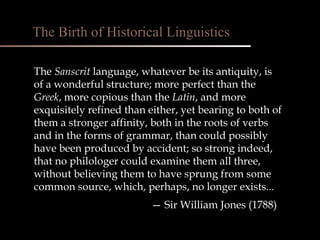

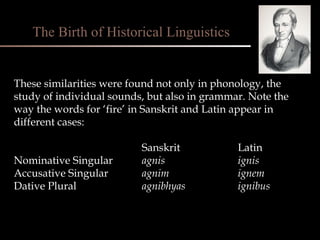

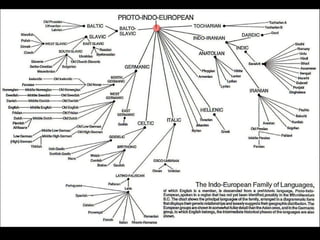

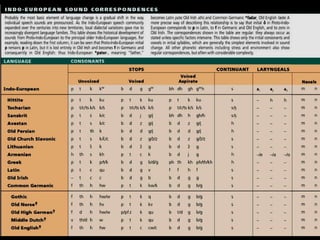

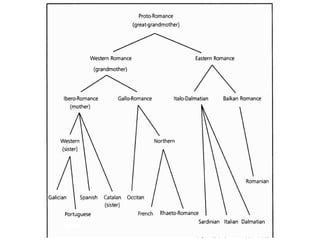

2) It examines the origins and development of languages, noting similarities between languages like Sanskrit, Latin, and others that suggest a common ancestral language.

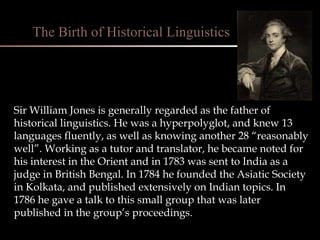

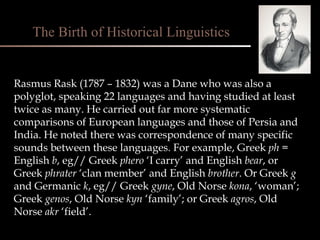

3) It outlines the work of early historical linguists who began systematically comparing languages and reconstructing proto-languages.

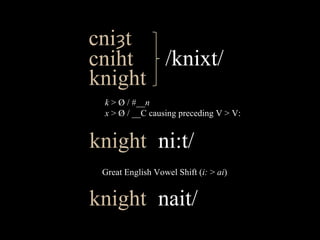

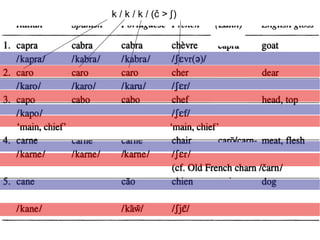

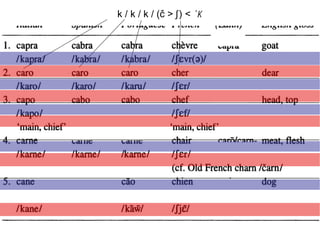

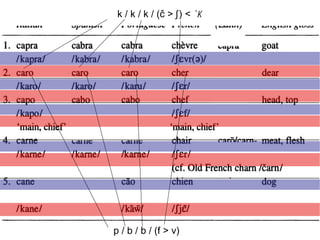

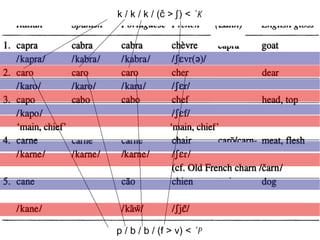

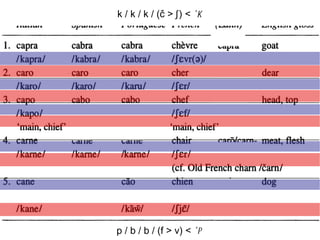

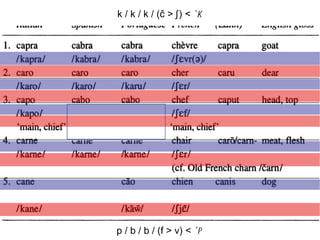

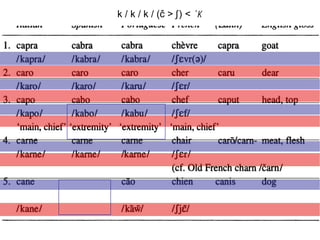

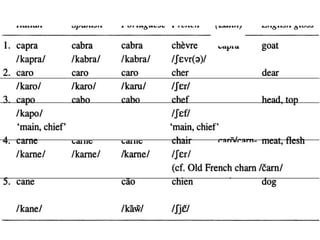

![- If a language has a long written tradition, conventional spellings (traditional, received orthography) can provide important evidence of earlier pronunciations. e.g., English knight German Knecht ‘groom’ Swedish knekt ‘soldier’ - In the many English borrowings from French (at different time periods), we witness frozen remnants of a series of sound changes which took place in that language, where initial k first became č and then š . Latin caput ‘head’ French chef ‘main, chief’ English borrowings: c aptain, ch ieftain, ch ief, and ch ef [ š ef] Conventional Spellings](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/class04histling-110124110354-phpapp02/85/Class-04-hist-ling-40-320.jpg)

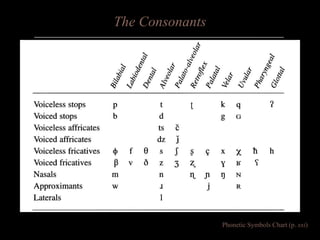

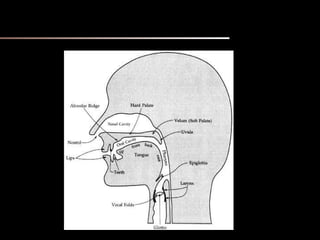

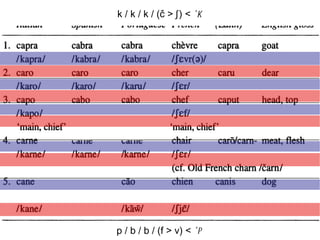

![Speech sounds can be classified on two distinct levels: Phonetic . This refers to the surface level of speech. Uttered sounds ( phones ) are conventionally transcribed in square brackets ( e.g., [p]). Phonemic . This refers to the way sounds are organized in the mind of a speaker. The phoneme is a minimally-contrastive ( i.e., significant) unit of sound conventionally enclosed in back-slashes ( e.g., /p/). Phonemes can have different surface pronunciations ( allophones ) in different environments , and are defined by distribution and contrast . In the English words pin and bin , /p/ and /b/ are distinct phonemes because they appear in identical environments ( e.g., at the beginning of words before i ) and yet contrast meanings (this is called a minimal pair ). In the words pin [p h in] and spin [spin], /p/ is still a single phoneme despite its different pronunciations (with and without aspiration). This is because English does not meaningfully distinguish [p] and [p h ]. Phonetic vs. Phonemic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/class04histling-110124110354-phpapp02/85/Class-04-hist-ling-41-320.jpg)