This document provides an overview of sequencing, cost-efficiency and fiscal sustainability of social protection systems in developing countries. It discusses how countries can transition from informal to more formal social protection arrangements over time. The document also examines how countries can continually assess vulnerabilities and identify cost-efficient social protection options through cost-benefit analysis. It explores options for creating fiscal space for social protection through embedding it in national development planning.

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

Social assistance programmes are non-contributory transfer programmes targeted at the poor and

those vulnerable to poverty and shocks. There is no universal consensus on the types of

interventions covered by the social assistance label. Common examples include cash transfers

(conditional cash transfers (CCTs) which are transfers to poor households conditional on specific

behavior) and unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) like non-contributory pensions, etc.); in-kind

transfers (e.g. food transfers); fee waivers (health fees, school fees, scholarships); utility

subsidies (e.g. electricity, housing and water) and so on.

Labour market interventions are aimed at protecting people who are in the labour market or at

poor people who are able to work.16

For the purpose of this paper, we differentiate between three types of social protection

arrangements17: (i) informal; (ii) semi-formal; and (iii) formal (public and private) arrangements.

Informal arrangements are based on friends and family (―kinship‖).18 Semi-formal arrangements

are based on voluntary or membership associations, civil society organizations (CSOs) (e.g. non-

governmental organizations (NGOs), trade unions). Formal arrangements are based on public

actors (i.e. the central or local government) and private actors (i.e. insurance companies (and

banks)).

Social protection can be arranged informally, semi-formally or formally. Various actors are

involved in these different types of arrangements. In the absence of formal social protection

mechanisms and—oftentimes—market mechanisms (for instance for credit and insurance

products), people in many developing countries have historically reverted to friends and family

for help in the face of adverse conditions.19 This is what we define as traditional and informal

social protection arrangements. The exact mechanisms of social protection provided in this

informal way very much depend on the particular traditions of the society in question. Likewise,

16

It should be noted that our definition of labour market interventions is broader than the definition by the

Governance and Social Development Resource Center that only counts ―[l]abour market interventions [that] provide

protection for poor people who are able to work‖ (GSDRC 2012). Labour market interventions include (vocational)

training and skills development and changes to labour legislation. They also include labour market measures that

likely fall under one of the other two areas of social protection (social insurance or social assistance) but are focused

on the labour market, like unemployment insurance, and part-time unemployment benefits. Public works

programmes (the poor working for food or cash), can be considered labour market interventions, but they are also

sometimes referred to as social assistance, since they basically function like conditional transfers (i.e. cash or food is

handed out in return for work on public infrastructure projects).

17

It should be noted that this is the authors‘ own elaboration. We settled on this tentative typology to ease

understanding of the landscape of possible arrangements of social protection. There is no generally accepted

definition of ―formal‖ and ―informal‖ social protection arrangements in the literature. While Holzmann and

Jø rgensen (2001) identify three main arrangements of social protection (public, market based and informal) as do

Hoogeveen at al. (2004) (formal, market based and informal), Mohanty (2011) refers to CSOs as actors in semi-

formal arrangements of social protection. Gentilini and Omamo (2009) consider both public and private actors to be

―formal‖ actors in social protection arrangements. Our categorization includes three categories of social protection

arrangements: social protection through public and private actors (formal), social protection through community,

groups, or member-based organizations (semi-formal) and social protection through households (informal).

18

UN (2000).

19

Mendola (2010). For a literature review on how people cope in the absence of publicly provided social protection

and often not accessible credit and insurance markets in low-income settings, please refer to Mendola (2010). For an

overview of how people cope with risk in an environment of non-inclusive markets, please refer to Mendoza and

Thelen (2008).

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-5-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

burial

societies,

Rotating

Credit and

Savings

Associations

(ROSCAs))

Informal****

family/kinship remittances /

(blood- direct money

related), transfer

friends gift exchange / in-

kind exchange

Sources: Own elaboration based on Dekker (2008), Dhemba, Gumbo and Nvamusara (2002), GSDRC (2012),

Holzmann and Jø rgensen (2001), Mohanty (2011).

* Churchill and Matul (2012) differentiate between formal providers of microinsurance (e.g. insurance companies),

and what we call ―semi-formal‖ providers (e.g. cooperatives, community-based organizations, mutuals, friendly

societies).

** Devereux (2010, p.13) broadly defines civil society to include ―[…] trade unions, rights-based NGOs,

representatives of special interest groups (women, children, pensioners, people with disabilities, people affected by

HIV and AIDS, homeless people, youth) community-based organisations (CBOs) and faith-based organisations

(FBOs), as well as activist academics and the independent media.‖

*** While we do recognize that NGO‘s can also be international actors (e.g. Save the Children), we mostly

considered nationally based NGOs.

**** We consider informal social protection to be solely based on individuals and households. However, we do

recognize the argument that communities are sometimes extended families.

2.2. Limitations of Informal and Semi-formal Social Protection

A major part of the world‘s population still relies on informal arrangements as the main source of

social protection. 40 Informal and semi-formal social protection, however, is present in most

developing countries: it has developed to fill gaps at the community and family/household level

that government policies have not been able (or willing) to address 41 or that markets have not

managed to (or have not been willing to) reach.42

40

Holzmann and Jø rgensen (2001); Hoogeveen et al. (2004). Comprehensive social protection systems exist in only

one-third of countries, where 28 percent of the global population lives; however, most of these systems cover only

workers in formal employment ILO (2010a, p.33). According to the ILO (2010a, p.33), only around 20 percent of

the global working-age population and their families have access to comprehensive social protection. It is roughly

estimated that somewhere between 20 percent and 60 percent of the global population has access to basic social

protection only ILO (2010a, p.33). According to the ILO, those enjoying only a basic level of income security

(guaranteeing income at the level of the poverty line) at all stages of the life cycle as well as access to essential

health services are considered to benefit from basic social protection, or i.e., the social protection floor (ILO 2010a,

p.22).

41

Dercon (2002).

42

For an analysis of how to make credit markets more inclusive for the poor, please refer to Mendoza and Thelen

(2008).

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-9-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

when embedding existing non-formal social protection arrangements into their development

strategies.

Public support has been found to be a strong driving force behind the successful social protection

country cases Brazil and South Africa.99 Both cases demonstrate that the formalization of social

protection initiatives, through writing them into law, makes it more likely that they will be taken

to scale or institutionalized.100 According to Pero and Szerman (2005):

―The New [Brazilian] Constitution was ambitious: it settled social-democrat guidelines

for social policy, stressing the universality of coverage and benefits, thus opposing the

patterns prevailing until the 1970s. […] the use of selectivity criteria to distribute benefits

to the most needy was also introduced. Furthermore, the Constitution deepened the

ongoing decentralization process, strengthening the fiscal and administrative autonomy of

sub-national governments.‖101

One of the aspects pushed by Brazil‘s new Constitution was the decentralization of spending and

better targeting of social expenditure for those who needed it most. 102 Despite high social

spending, social indicators in Brazil deteriorated further throughout the 1980s 103 and first

determined steps to breaking the inability of social spending to reduce poverty and inequality in

Brazil and towards implementing a new social development strategy were only adopted by a new

government as of 1995. 104 Improvements in social protection spending, policy design and

implementation in Brazil owe much to partnerships between the federal government, sub-

national governments, civil society and the private sector. An important building block of

Brazil‘s Bolsa Famí (the Bolsa Escola programme) was first developed and implemented at

lia

the municipal level before being scaled up to the national level.105 The partnership with civil

society has helped the Brazilian government to improve the accuracy of Bolsa Famí lia’s

106

beneficiary registry, and hence its targeting accuracy over time.

Strong political will at the federal level is also a key prerequisite for the successful expansion of

social protection. A review 107 of social protection in Southern Africa concludes that social

protection interventions have higher chances of succeeding if they are driven by political will,

i.e. if they are government-led from the beginning than if they are donor-driven. For instance,

successful social pension schemes for all older citizens were introduced in Lesotho (2004) and

Swaziland (2005).108 These schemes were designed and implemented without donor support.109

In general, in Southern Africa, government-led SP systems in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia,

99

Devereux (2011); UNDP (2012a).

100

Devereux (2010).

101

Pero and Szerman (2005, p.5).

102

Pero and Szerman (2005).

103

Brazil‘s GINI index peaked in 1989 at 63, making Brazil one of the most unequal societies in the world (World

Bank 2012).

104

World Bank (1988) as quoted in Pero and Szerman (2005). For detailed information on Brazil‘s social

development strategy under Cardoso, please refer to Faria (2002).

105

De Janvry (2005); Pero and Szerman (2005).

106

Lindert et al.(2007).

107

Devereux (2010).

108

Devereux (2010).

109

Devereux (2010).

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-17-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

and longer term. A dynamic and comprehensive approach also implies that we need a better

understanding of the long-term effects of social protection spending on economic growth and

human development.218 If social protection programmes are debt financed, then the impacts of

debt on the underlying economic growth rate, inflation and welfare are also need to be assessed.

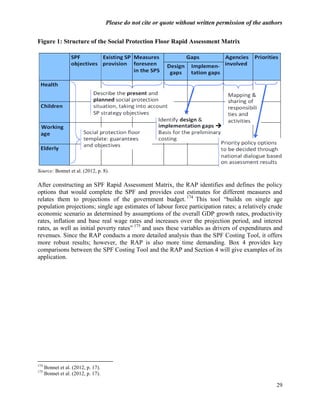

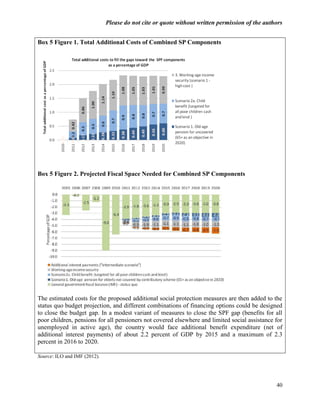

4.2. Practice of Social Protection Fiscal Sustainability Analysis

In our view, analyzing fiscal sustainability of social protection programmes in developing

countries is about connecting the dots between costs, fiscal space and the potential benefits that

such social protection programmes are associated with.

With countries increasingly recognizing the importance of social protection, efforts have been

made to yield better understanding of fiscal sustainability of specific social protection measures

or full-fledged social protection systems. The recent collaborative work among various

international organizations (ILO, IMF, UNDP, UNICEF, World Bank, and others) in assessing

the fiscal cost and fiscal space available for the implementation of social protection floor policies

over the medium term has helped ―provide the factual bases for national dialogues on alternative

policy options, implementation priorities and the phasing-in of SPF policies‖.219 Despite being a

quite simplified model, the RAP has emerged as a useful analytical tool to tackle the technical

questions associated with social protection that developing countries face in their policy making

process.

In the following sub-section, we will review several country studies (Viet Nam, El Salvador,

Mozambique, and Thailand) applying the RAP to assess fiscal space, budget allocations and

fiscal sustainability of social protection programmes over the short and medium term. These

RAP studies are supported by a national consultation process through which the range, level and

priorities of social protection measures, financing options and fiscal space have been

discussed.220

A dynamic approach to fiscal sustainability of social protection requires a costing exercise that

not only estimates the start-up costs of social protection measures but also projects the

maintaining and operating costs over the medium and long term. The data constraints limit the

218

Roy, Heuty and Letouzé(2009). Besides long-term fiduciary sustainability, Roy, Heuty and Letouzé(2009) point

out that for developing countries which fiscal space relying on volatile and exogenous sources of external finance

such as bilateral aid, concessional and non-concessional foreign borrowing, long-term fiscal sustainability also

requires minimizing the reliance on external finance over longer term.

219

ILO and IMF (2012, p. 7). ―In what appears to be emerging as a standard procedure, the UN is leading the

costing exercise and developed the various benefit scenarios according to the national priorities and the recently

approved NBSS strategy, helped by macroeconomic and general government operations data provided by the IMF

for the model. The IMF led the analysis on the creation of fiscal space for government priorities in a medium-term

fiscal framework […]‖.

220

ILO and IMF (2012); IMF (2012a).

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-37-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

Bibliography

ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2010. Weaving Social Safety Nets. Mandaluyong City,

Philippines. [www.adb.org/publications/weaving-social-safety-nets].

ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2009. ―Social Protection: Reducing Risks, Increasing

Opportunities.‖ Manila.

Aguzzoni, Luca. 2011. ―The Concept of Fiscal Space and Its Applicability to the Development

of Social Protection Policy in Zambia.‖ ILO Extension of Social Security Series, ESS

Paper 28. International Labour Organization, Geneva.

[www.socialsecurityextension.org/gimi/gess/RessShowRessource.do?ressourceId=28148

].

Alderman, Harold and Ruslan Yemtsov. 2012. ―Productive Role of Safety Nets.‖ Social

Protection and Labor Discussion Paper No. 1203. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-

papers/430578-1331508552354/1203.pdf].

AusAid. 2012. ―Informal Social Protection in Pacific Island Countries: Strengths and

Weaknesses.‖ Commonwealth of Australia.

[www.ausaid.gov.au/aidissues/foodsecurity/Documents/informal-social-protection.pdf].

Barrientos, Armando. 2010. ―Social Protection and Poverty.‖ Social Policy and Development

Programme Paper Number 42. United Nations Research Institute for Social

Development, Geneva. [www.abdn.ac.uk/sustainable-international-

development/uploads/files/Barrientos-pp.pdf].

Barrientos, Armando. 2008. ―Financing Social Protection.‖ In Armando Barrientos and David

Hulme, eds., Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest: Concepts, Policies and Politics.

London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Barrientos, Armando and David Hulme. 2008. ―Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest in

Developing Countries: Reflections on a Quiet Revolution.‖ BWPI Working Paper 30.

Brooks World Poverty Institute, The University of Manchester, Manchester.

[www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/resources/Working-Papers/bwpi-wp-3008.pdf].

Behrendt, Christina. 2011. ―ILO Basic Social Protection Costing Models and Policy

Implications.‖ Presentation given at ODI International Conference on Financing Social

Protection in LICs: Finding the Common Ground, London, 26-27 May 2011.

International Labour Office, Social Security Department, Geneva. [www.social-

protection.org/gimi/gess/RessShowRessource.do?ressourceId=23847].

Behrman, Jere R., Maria Cecilia Calderon, Olivia Mitchell, Javiera Vasquez and David Bravo,

2011. ―First-Round Impacts of the 2008 Chilean Pension System Reform.‖ PARC

Working Paper Series 11-01. Population Aging Research Center, University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. [http://repository.upenn.edu/parc_working_papers/33].

Bester, Hennie, Doubell Chamberlain, Ryan Hawthorne, Stephan Malherbe and Richard Walker.

2004. ―Making Insurance Markets Work for the Poor in South Africa - Scoping Study.‖

Johannesburg, South Africa: Genesis Analytics.

Betcherman, Gordon, Martin Godfrey, Susana Puerto, Friederike Rother and Antoneta Stavreska.

2007. ―A Review of Interventions to Support Young Workers: Findings of the Youth

Employment Inventory.‖ SP Discussion Paper No. 0715. World Bank, Washington D. C.

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-55-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-

papers/Labor-Market-DP/0715.pdf].

Bhattamishra, Ruchira and Christopher B. Barrett. 2010. ―Community-Based Risk Management

Arrangements: A Review.‖ World Development 38(7):923-932.

Black Sash. 2010. ―Social Assistance: A Reference Guide for Paralegals.‖ Cape Town.

BMZ (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2011.

―Microinsurance as a Social Protection Instrument.‖ Berlin.

[www.bmz.de/en/publications/topics/social_security/FlyerMicroinsurance.pdf].

Bonilla García, A. and J.V. Gruat. 2003. ―Social Protection: A Life Cycle Continuum Investment

for Social Justice, Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development.‖ Geneva:

International Labour Office.

[www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/download/lifecycl/lifecycle.pdf].

Bonnet, Florence, Michael Cichon, Carlos Galian, Gintare Mazelkaite. 2012. ―Analysis of the

Viet Nam National Social Protection Strategy (2011-2020) in the context of Social

Protection Floor objectives: A rapid assessment.‖ ESS Paper No. 32. Global Campaign

on Social Security and Coverage for All. International Labour Office, Social Security

Department, Geneva. [www.social-

protection.org/gimi/gess/RessShowRessource.do?ressourceId=30497].

Britto, Tatiana. 2006. ―Conditional Cash Transfers in Latin America.‖ In Social Protection: The

Role of Cash Transfers. Poverty in Focus, June 2006: 15-17. International Poverty

Centre, UNDP, Brasilia. [www.ipc-undp.org/pub/IPCPovertyInFocus8.pdf].

Calvo, Esteban, Fabio M. Bertranou and Evelina Bertranou. 2010. ―Are Old-age Pension

System Reforms: Moving Away from Individual Retirement Accounts in Latin

America?‖ Journal of Social Policy 39(2): 223–234.

Chen, Martha Alter, Renana Jhabvala, Frances Lund. 2002. ―Supporting Workers in the Informal

Economy: A Policy Framework.‖ Working Paper on the Informal Economy prepared for

the International Labor Organisation (Employment Sector) (2002/2).

[www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---

ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_122055.pdf].

Cook, Sarah. 2009. ―Social Protection in East and South East Asia: A Regional Review.‖

Prepared as part of a Social Protection Scoping Study funded by the Ford Foundation.

Centre for Social Protection, Institute of Development Studies.

[www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/SocialProtectioninEastandSouthEastAsia.pdf].

Cook, Sarah and Naila Kabeer. 2010. ―Introduction: Exclusions, Deficits and Trajectories.‖ In

Sarah Cook and Naila Kabeer, eds., Social Protection as Development Policy: Asian

Perspectives. New Delhi: Routledge India.

Cook, Sarah and Naila Kabeer. 2009. ―Socio-economic Security Over the Life Course: A Global

Review of Social Protection.‖ Prepared as the final report of a Social Protection Scoping

Study funded by the Ford Foundation. Centre for Social Protection, Institute of

Development Studies.

[www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/AGlobalReviewofSocialProtection.pdf].

Churchill, Craig and Michal Matul, eds. 2012. Protecting the Poor: A Microinsurance

Compendium, Volume 2. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [www.munichre-

foundation.org/dms/MRS/Documents/MicroinsuranceCompendium_VolII0/Microinsuran

ceCompendium_VolII.pdf].

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-56-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

Churchill, Craig, ed. 2006. Protecting the Poor: A Microinsurance Compendium, Volume 1.

Geneva: International Labour Organization.

CRISIL (Credit Rating Information Services of India Limited). 2012. ―Budget Analysis.‖ March

2012. Powai, Mumbai.

[www.crisilresearch.com/Union_Budget/Budget%20Analysis%202012-13.pdf].

De Janvry, Alain, Frederico Finan, Elisabeth Sadoulet, Donald Nelson, Kathy Lindert, Bé dicte

né

de la Brière, and Peter Lanjouw. 2005. ―Brazil‘s Bolsa Escola Program: The Role of

Local Governance in Decentralized Implementation.‖ SP Discussion Paper No. 0542.

World Bank, Washington, D.C.

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-

papers/Safety-Nets-DP/0542.pdf].

Dekker, Andriette Hendrina. 2008. ―Mind the Gap: Suggestions for Bridging the Divide between

Formal and Informal Social Security.‖ Law, Democracy & Development 12(1):117-131.

[www.ldd.org.za/index.php?option=com_zine&view=article&id=54%3Amind-the-gap-

suggestions-for-bridging-the-divide-between-formal-and-informal-social-

security&Itemid=14].

Dercon, Stefan. 2011. ―Social Protection, Efficiency and Growth.‖ WPS/2011-17. Centre for the

Study of African Economies, University of Oxford.

[www.csae.ox.ac.uk/workingpapers/pdfs/csae-wps-2011-17.pdf].

Dercon, Stefan. 2002. ―Income Risk, Coping Strategies, and Safety Nets.‖ World Bank Research

Observer 17(2): 141-166.

Dercon, Stefan, Tessa Bold, Joachim De Weerdt and Alula Pankhurst. 2004. ―Extending

Insurance? Funeral Associations in Ethiopia and Tanzania.‖ OECD Development Centre

Working Paper No. 240. OECD Development Centre, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France.

[www.oecd.org/social/povertyreductionandsocialdevelopment/34106491.pdf].

Dercon, Stefan and Pramila Krishnan. 2000. ―In Sickness and in Health: Risk Sharing within

Households in Rural Ethiopia.‖ Journal of Political Economy 108(4):688-727.

Devereux, Stephen. 2011. ―Social Protection in South Africa: Exceptional or Exceptionalism?‖

Canadian Journal of Development Studies 32(4):414-425.

Devereux, Stephen. 2010. ―Building Social Protection Systems in Southern Africa.‖ Paper

prepared in the framework of the European Report on Development 2010.

[http://erd.eui.eu/media/BackgroundPapers/Devereaux%20-

%20BUILDING%20SOCIAL%20PROTECTION%20SYSTEMS.pdf].

Devereux, Stephen. 1999. ―Making Less Last Longer: Informal Safety Nets in Malawi.‖ IDS

Discussion Paper No. 373. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK.

[www.ids.ac.uk/files/Dp373.pdf].

Devereux, Stephen and Rachel Sabates-Wheeler. 2004. ―Transformative Social Protection.‖ IDS

Working Paper 232. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK.

[www.ids.ac.uk/files/Wp232.pdf].

DFID (United Kingdom Department for International Development).2005. ―Social Transfers and

Chronic Poverty: Emerging Evidence and the Challenge Ahead.‖ Practice Paper. London.

Dhemba, Jotham, P. Gumbo and J. Nvamusara. 2002. ―Social Security in Zimbabwe.‖ Journal of

Social Development in Africa 17(2): 111-131.

[http://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/African%20Journals/pdfs/social%20development/vol17

no2/jsda017002008.pdf].

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-57-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

Drechsler, Denis and Johannes Jütting. 2005. ―Is there a Role for Private Health Insurance in

Developing Countries?‖ Discussion Paper 517. German Institute for Economic Research,

Berlin. [www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.43736.de/dp517.pdf].

Du Toit, Andries and David Neves. 2009. ―Informal Social Protection in Post-Apartheid Migrant

Networks: Vulnerability, Social Networks and Reciprocal Exchange in the Eastern and

Western Cape, South Africa.‖ BWPI Working Paper No. 74. Brooks World Poverty

Institute, Manchester, UK. [www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/resources/Working-

Papers/bwpi-wp-7409.pdf].

Faria, Vilmar E. 2002. ―Institutional Reform and Government Coordination in Brazil‘s Social

Protection Policy. CEPAL Review 77.

Gallardo, Eduardo. 2008. ―Chile‘s Private Pension System adds Public Payouts for Poor.‖ New

York Times 10 March. [www.nytimes.com/2008/03/10/business/worldbusiness/10iht-

pension.4.10887983.html].

Garcí A.B. and J.V. Gruat. 2003. ―Social Protection: A Life Cycle Continuum Investment for

a,

Social Justice, Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development.‖ Geneva: ILO.

Gentilini, Ugo and StevenWere Omamo. 2009. ―Unveiling Social Safety Nets.‖ WFP Occasional

Paper 20. World Food Programme, Rome. [www.wfp.org/sites/default/files/OP20%20-

%20Unveiling%20Social%20Safety%20Nets%20-%20English.pdf].

Government of India. 2012a. ―Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act,

2005: Report to the People, 2nd February 2012.‖ Ministry of Rural Development,

Department of Rural Development, New Delhi.

[http://nrega.nic.in/circular/Report%20to%20the%20people_english%20web.pdf].

Government of India. 2012b. ―Economic Survey 2011–12.‖ Ministry of Finance, New Delhi.

[http://indiabudget.nic.in/survey.asp].

Gringle, Merilee. 2010. ―Social Policy in Development: Coherence and Cooperation in the Real

World.‖ Faculty Research Working Paper Series 10-024. Harvard Kennedy School,

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

GSDRC (Governance and Social Development Resource Center). 2012. ―Social Protection.‖

[www.gsdrc.org/go/topic-guides/social-protection/types-of-social-protection#ins].

Accessed on 7 September.

G20 (Group of Twenty), 2011. CommuniquéG20 Leaders Summit. 3-4 November 2011. Cannes:

G20.

Hagen-Zanker, Jessica and Anna McCord. 2011. ―The Affordability of Social Protection in the

Light of International Spending Commitments.‖ ODI Social Protection Series. Overseas

Development Institute, London. [www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/7086.pdf].

Heller, Peter. 2005. ―Understanding Fiscal Space.‖ IMF Policy Discussion Paper. International

Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

Hoogeveen, Johannes, Emil Tesliuc, Renos Vakis, and Stefan Dercon. 2004. ―A Guide to the

Analysis of Risk, Vulnerability and Vulnerable Groups.‖ Social Protection Unit. Human

Development Network. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSRM/Publications/20316319/RVA.pdf].

Holzmann, Robert and Steen Jørgensen. 2001. ―Social Risk Management: A New Conceptual

Framework for Social Protection, and Beyond.‖ International Tax and Public Finance

8(4):529-556.

Hu, Aidi. 2010. ―Social Protection Floor for All: A UN Joint Crisis Iniative‖. In Sri Wening

Handayani ed., Enhancing Social Protection in Asia and the Pacific: The Proceedings of

58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-58-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

the Regional Workshop. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

[www.adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2011/proceedings-enhancing-social-protection.pdf].

IEG (Independent Evaluation Group). 2007. Sourcebook for Evaluating Global and Regional

Partnership Programs: Indicative Principles and Standards. Washington, DC : World

Bank. [https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6601].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2012a. ―The youth employment crisis: A call for

action.‖ Resolution and conclusions of the 101st Session of the International Labour

Conference, Geneva, 2012. International Labour Office, Geneva.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2012b. ―Cambodia. Social Protection Expenditure and

Performance Review.‖ Final Draft. EU/ILO Partnership Programme Project ―Improving

Social Protection and Promoting Employment" in cooperation with GIZ Phnom Penh.

February 2012. International Labour Office, Social Security Department, Geneva.

[www.socialprotection.gov.kh/documents/CrossCuttingIssue/SocialBudget/SPExpenditur

ePerformanceReview.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2012c. ―The United Nations Social Protection Floor

Joint Team in Thailand: A Replicable Experience for other UN Country Teams.‖

International Labour Organization, Geneva. [www.socialprotectionfloor-

gateway.org/files/Thailand_SPF.Costing_led_by_ILO_using_RAP.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2011. ―Social Protection Floor for a Fair and Inclusive

Globalization.‖ Report of the Advisory Group Chaired by Michelle Bachelet, Convened

by the ILO with the Collaboration of the WHO. International Labour Organization,

Geneva. [www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/secsoc/downloads/bachelet.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2010a. World Social Security Report 2010/11:

Providing Coverage in Times of Crisis and Beyond. Geneva.

[www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/secsoc/downloads/policy/wssr.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2010b. ―Extending Social Security to All: A Guide

Through Challenges and Options.‖ International Labour Organization, Geneva.

[www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---

publ/documents/publication/wcms_146616.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2008. ―Can Low-income Countries Afford Basic

Social Security?‖ Social Security Policy Briefings, Paper 3. International Labour

Organization, Geneva. [www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2008/108B09_73_engl.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2001. ―Report VI. Social Security: Issues, Challenges

and Prospects. Sixth Item on the Agenda.‖ International Labour Conference 89th Session.

[www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc89/pdf/rep-vi.pdf].

ILO (International Labour Organization) and IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2012.

―Towards Effective and Fiscally Sustainable Social Protection Floors.‖ Preliminary Draft

10 May 2012. International Labour Office, Geneva and International Monetary Fund,

Washington, D.C.

[www.socialsecurityextension.org/gimi/gess/RessShowRessource.do?ressourceId=30810

].

ILO (International Labour Organization) and UNDP (United Nations Development Programme).

2011. ―Inclusive and Resilient Development: The Role of Social Protection.‖ Mimeo.

ILO (International Labour Organization) and World Bank. 2012. ―ILO-World Bank Joint

Synthesis Report: Inventory of Policy Responses to the Financial and Economic Crisis.‖

Geneva and Washington, D.C: ILO and World Bank.

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-59-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

[www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---

emp_elm/documents/publication/wcms_186324.pdf].

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2012a. ―Republic of Mozambique: Fourth Review under the

Policy Support Instrument and Request for Modification of Assessment Criteria‖. IMF

Country Report 12/148. Washington DC: IMF.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2012b. ―Fiscal Monitor October 2012, Taking Stock: A

Progress Report on Fiscal Adjustment.‖ IMF World Economic and Financial Surveys.

IMF, Washington D.C. [www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2012/02/pdf/fm1202.pdf].

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2001. ―Government Financial Statistics Manual.‖

Washington, D.C.

James, Estelle, Alejandra Cox Edwards and Augusto Iglesias. 2010. ―Chile‘s New Pension

Reforms.‖ Policy Report No. 326. National Center for Policy Analysis, Dallas, TX.

[www.ncpa.org/pdfs/st326].

Jung, Young-Tae and Dong-Myeon Shin. 2002. ―Social Protection in South Korea.‖ In Erfried

Adam, Michael von Hauff and Marei John, eds., Social Protection in Southeast & East

Asia. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Bonn. [http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/01443.pdf]

Kingdom of Cambodia. 2010. ―Towards a Social Protection Strategy for the Poor and

Vulnerable: Outcomes of the consultation process.‖ Council for Agricultural and Rural

Development, July 2010.

[www.socialprotection.gov.kh/documents/publication/background%20note%20social%2

0protection%20en.pdf].

Knox-Vydmanov, Charles. 2011. ―The price of income security in older age: cost of a universal

pension in 50 low- and middle-income countries.‖ Pension Watch Briefings on social

protection in older age, Briefing no. 2, HelpAge International, London. [www.pension-

watch.net/about-social-pensions/about-social-pensions/pension-watch-briefing-series/].

Lagomarsino, Gina, Alice Garabrant, Atikah Adyas, Richard Muga, Nathaniel Otoo. 2012.

―Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage: Health Insurance Reforms in Nine

Developing Countries in Africa and Asia.‖ The Lancet 380(9845): 933-943.

Levy, Santiago. 2006. Progress Against Poverty: Sustaining Mexico’s Progresa-Oportunidades

Program. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Lindert, Kathy, Anja Linder, Jason Hobbs, Bénédicte de la Brière. 2007. ―The Nuts and Bolts of

Brazil‘s Bolsa Família Program: Implementing Conditional Cash Transfers in a

Decentralized Context.‖ SP Discussion Paper No. 0709. World Bank, Washington. D.C.

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLACREGTOPLABSOCPRO/Resources/BRBolsa

FamiliaDiscussionPaper.pdf].

Mendola, Mariapia. 2010. ―Migration and Informal Social Protection in Rural Mozambique.‖

Paper prepared for the Workshop ―Promoting Resilience through Social Protection in

Sub-Saharan Africa‖ Organised by the European Report on Development in Dakar, 28-30

June. [http://erd.eui.eu/media/BackgroundPapers/Mendola.pdf].

Mendoza, Ronald U. and Nina Thelen. 2008. ―Innovations to Make Markets More Inclusive for

the Poor.‖ Development Policy Review 26(4):427-458.

Mohanty, Manoranjan. 2011. ―Informal Social Protection and Social Development in Pacific

Island Countries: Role of NGOs and Civil Society.‖ Asia-Pacific Development Journal

18(2):25-56. [www.unescap.org/pdd/publications/apdj-18-2/2-Mohanty.pdf].

Newson, Lara and Astrid Walker Bourne. 2011. ―Financing social pensions in low- and middle-

income countries.‖ Pension Watch Briefings on social protection in older age, Briefing

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-60-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

no. 4. HelpAge International, London. [www.pension-watch.net/about-social-

pensions/about-social-pensions/pension-watch-briefing-series/].

O‘Cleirigh, Earnan. 2009. ―Affordability of Social Protection Measures in Poor Developing

Countries.‖ In Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: Social Protection. Paris: Organisation for

Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2012. ―OECD‘s Current

Tax Agenda 2012.‖ Paris. [www.oecd.org/ctp/1909369.pdf].

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2011. ―Revenue Statistics

1965-2010: 2011 Edition.‖ Paris.

[www.oecd.org/tax/taxpolicyanalysis/revenuestatistics1965-20102011edition.htm].

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2009. Social Protection.

Paris.

Olivier, MP, E Kaseke and LG Mpedi. 2008. ―Informal Social Security in Southern Africa:

Developing a Framework for Policy Intervention.‖ Paper prepared for presentation at the

International Conference on Social Security organised by the National Department of

Social Department, South Africa, 10-14 March 2008, Cape Town.

[http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/CPSI/UNPAN030287.pdf].

Ortiz, Isabel, Jingqing Chai and Matthew Cummins. 2011. ―Identifying Fiscal Space: Options for

Social and Economic Development for Children and Poor Households in 182 Countries.‖

UNICEF Social and Economic Policy Working Paper. UNICEF, New York.

[www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Fiscal_Space_-_17_Oct_-_FINAL.pdf].

Ortiz, Isabel and Jennifer Yablonski. 2010. ―Investing in People: Social Protection for All.‖ In

Sri Wening Handayani ed., Enhancing Social Protection in Asia and the Pacific: The

Proceedings of the Regional Workshop. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

[www.adb.org/sites/default/files/pub/2011/proceedings-enhancing-social-protection.pdf].

Pacheco Santos, Leonor Maria, Romulo Paes-Sousa, Edina Miazagi, Tiago Falcã Silva, Ana

o

Maria Medeiros da Fonseca. 2011. ―The Brazilian Experience with Conditional Cash

Transfers: A Successful Way to Reduce Inequity and to Improve Health. Draft

background paper commissioned by the World Health Organization for the World

Conference on Social Determinants of Health, held 19-21 October 2011, in Rio de

Janeiro, Brazil.

[www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/draft_background_paper1_brazil.pdf].

Pauly, Mark V., Peter Zweifel, Richard M. Scheffler, Alexander S. Preker and Mark Bassett.

2006. ―Private Health Insurance In Developing Countries.‖ Health Affairs 25(2):369-379.

Pero, Valéria and Dimitri Szerman. 2005 (first draft). ―The New Generation of Social Programs

in Brazil.‖ Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janiero Instituto de Economia.

[www.ie.ufrj.br/eventos/pdfs/seminarios/pesquisa/the_new_generation_of_social_progra

ms_in_brazil.pdf].

Rabi, Amjad. 2012. ―Integrating a System of Child Benefits into Egypt‘s Fiscal Space: Poverty

Impact, Costing, and Fiscal Space.‖ UNICEF, New York.

[www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Egypt.Costing_Tool_application.pdf].

Roy, Rathin, Antoine Heuty and Emmanuel Letouzé. 2009. ―Fiscal Space for What? Analytical

Issues from a Human Development Perspective.‖ In Rathin Roy and Antoine Heuty, eds.,

Fiscal Space: Policy Options for Financing Human Development. Sterling: Earthscan.

Royal Government of Cambodia. 2011. ―National Social Protection Strategy for the Poor and

Vulnerable.‖ Supported by UN ICEF.

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-61-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

[www.unicef.org/cambodia/National_Social_Protection_Strategy_for_the_Poor_and_Vul

nerable_Eng.pdf].

Samson, Michael. 2009. ―Social Cash Transfers and Pro-Poor Growth.‖ In Organisation for

Economic Cooperation and Development, ed., Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: Social

Protection. Paris. [www.oecd.org/dac/povertyreduction/43514563.pdf].

Schnitzer, Pascale. 2011. ―Design Options, Cost and Impacts of a Cash Transfer Program in

Senegal: Simulation Results.‖ UNICEF Senegal Country Office, Senegal.

[www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Senegal.Costing_Tool_application.pdf].

Shelton, Alison M. 2012. ―Chile‘s Pension System: Background in Brief.‖ CRS Report for

Congress R42449. Congressional Research Service, Monterey, CA.

[www.hsdl.org/?view&did=707798].

Soares, Sergei, Rafael Guerreiro Osó rio, Fábio Veras Soares, Marcelo Medeiros, Eduardo

Zepeda. 2007. ―Conditional Cash Transfers in Brazil, Chile and Mexico: Impacts upon

Inequality.‖ Working Paper No. 35. International Poverty Centre, United Nations

Development Programme, Brasilia. [www.ipc-undp.org/pub/IPCWorkingPaper35.pdf].

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2012. The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our

Future. New York: W.W. Norton.

Sumarto, Sudarno and Samuel Bazzi. 2011. ―Social Protection in Indonesia: Past Experiences

and Lessons for the Future.‖ Paper presented at the 2011 Annual Bank Conference on

Development Opportunities (ABCDE) jointly organized by the World Bank and OECD,

30 May-1 June 2011, Paris.

[http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTABCDE/Resources/7455676-

1292528456380/7626791-1303141641402/7878676-1306270833789/ABCDE-

Submission-Sumarto_and_Bazzi.pdf].

Tapia, Waldo. 2008. ―Description of Private Pension Systems.‖ OECD Working Papers on

Insurance and Private Pensions No. 22. OECD, Paris.

[www.oecd.org/insurance/privatepensions/41408080.pdf].

The Economist. 2012. ―New Cradles to Graves.‖ September 8.

[www.economist.com/node/21562210].

Tshoose, Clarence Itumeleng. 2010. ―The Impact of HIV/AIDS Regarding Informal Social

Security: Issues and Perspectives from a South African Context.‖ Potchefstroom

Electronic Law Journal 13(3):408-447.

[http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1744653##].

UN (United Nations). 2012. ―MDG Gap Task Force Report 2012: The Global Partnership for

Development: Making Rhetoric a Reality.‖ United Nations, New York.

[www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/mdg_gap/mdg_gap2012/mdg8report2012_eng

w.pdf].

UN (United Nations). 2000. ―Enhancing Social Protection and Reducing Vulnerability in a

Globalizing World: Report of the Secretary-General.‖ United Nations Economic and

Social Council, Commission for Social Development, E/CN.5/2001/2. New York.

[http://daccess-dds-

ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N00/792/23/PDF/N0079223.pdf?OpenElement].

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2012a. Africa Human Development Report

2012: Towards a Food Secure Future. New York: United Nations Development

Programme. [www.afhdr.org/the-report/].

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-62-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2012b. Case Studies of Sustainable

Development in Practice: Triple Wins for Sustainable Development. New York: United

Nations Development Programme. [www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Cross-

Practice%20generic%20theme/Triple-Wins-for-Sustainable-Development-web.pdf].

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2012c. ―Ensuring Inclusion: e-Discussion on

Social Protection.‖ UNDP Asia-Pacific Regional Centre, Bangkok. [www.snap-

undp.org/elibrary/Publications/SocialProtectionE-Discussion.pdf].

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and ILO (International Labour Organization).

2011. ―Sharing Innovative Experiences: Successful Social Protection Floor Experiences.‖

United Nations Development Programme: New York.

UNICEF (United Nations Children‘s Fund). 2008. ―Social Protection in Eastern and Southern

Africa: A Framework and Strategy for UNICEF.‖ UNICEF, New York.

[www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Social_Protection_Strategy(1).pdf].

UNICEF (United Nations Children‘s Fund) and ILO (International Labour Organization). 2011.

―UNICEF-ILO Social Protection Floor Costing Tool: Explanatory Note.‖ New York.

[www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Costing_Tool_Explanatory_Note.pdf].

UNICEF (United Nations Children‘s Fund) and ODI (Overseas Development Institute). 2009.

―Fiscal Space for Strengthened Social Protection: West and Central Africa.‖ Regional

Thematic Report 2 Study. UNICEF Regional Office for West and Central Africa, Dakar.

[www.unicef.org/wcaro/wcaro_UNICEF_ODI_2_Fiscal_Space.pdf].

UN NGLS (United Nations Non-Governmental Liaison Service). 2010. Decent Work and Fair

Globalization: A Guide to Policy Dialogue. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

[www.un-ngls.org/docs/un-ngls/decentwork.pdf].

Upreti, Bishnu Raj, Sony KC, Richard Mallett and Babken Babajanian, with Kailash Pyakuryal,

Safal Ghimire, Anita Ghimire and Sagar Raj. 2012. ―Livelihoods, Basic Services and

Social Protection in Nepal.‖ Working Paper 7. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium,

Overseas Development Institute. London. [www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/7784.pdf].

World Bank. 2012. ―World Development Indicators Database.‖ Washington, D.C. Accessed 30

August 2012. [http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators].

World Bank. 2006. ―Fiscal Policy for Growth and Development: An Interim Report.‖

Washington D.C.

World Bank. 1988. Brazil: Public Spending on Social Programs; Issues and Options. Report No

7086-BR. World Bank, Washington DC.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. The World Health Report 2010. Health Systems

Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva.

[www.who.int/whr/2010/whr10_en.pdf].

Yablonski, Jennifer and Michael O‘Donnell. 2009. Lasting Benefits: The Role of Cash Transfer

in Tackling Child Mortality. London: Save the Children UK.

[www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/Lasting_Benefits_low_res_comp_re

vd_1.pdf].

Zhang, Yanchun. 2012. ―European Sovereign Debt Crisis: An Unfolding Crisis Leading to an

Unraveling Euro Zone?‖ Strategic Policy Unit/UNDP Working Paper. United Nations

Development Programme, New York.

Zhang, Yanchun, Nina Thelen and Aparna Rao. 2012. ―Social Protection in Fiscal Stimulus

Packages.‖ In Caroline Harper, Nicola Jones, Ronald U. Mendoza, David Stewart and

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-63-320.jpg)

![Please do not cite or quote without written permission of the authors

Annex

Annex Box 1: Definitions of Social Protection

ADB (ADB 2009): ‗[…] policies and programs designed to reduce poverty and vulnerability by

promoting efficient labor markets, diminishing people‘s exposure to risks, enhancing their

capacity to protect themselves against hazards and interruption/loss of income.‘ ADB names five

main areas in social protection: labour markets, social insurance, social assistance, micro- and

area-based schemes and child protection.

DFID (DFID 2005): ‗[…] a sub-set of public actions—carried out by the state or privately—that

address risk, vulnerability and chronic poverty.‘ For operational reasons, DFID (2005) sub-

divides social protection into three key components: social insurance, social assistance and

setting and enforcing minimum standards.

ILO (García and Gruat 2003): ‗[…] the set of public measures that a society provides for its

members to protect them against economic and social distress that would be caused by the

absence or a substantial reduction of income from work as a result of various contingencies

(sickness, maternity, employment injury, unemployment, invalidity, old age, and death of the

breadwinner); the provision of health care; and, the provision of benefits for families with

children. This concept of social protection is also reflected in the various ILO standards.‘

IMF (IMF 2001): ‗[…] government outlays on social protection include expenditures on services

and transfers provided to individual person and households and expenditures on services

provided on a collective basis. […] Collective social protection services are concerned with

matters such as formulation and administration of government policy; formulation and

enforcement of legislation and standards for providing social protection; and applied research

and experimental development into social protection affairs and services.‘ Health care is not

included in the IMF definition of social protection expenses as it is classified as a separate

expense.

OECD (OECD 2009): ‗[…] social protection and empowerment provide security and unlock

human potential and thereby encourage poor people to take advantage of opportunities, which in

turn promotes more sustainable pro-poor growth strategies. Social protection cuts across all

sectors, and is considered important for breaking the intergenerational cycle of poverty, and for

achieving a social contract on nation-building and accelerating progress towards the MDGs.‘

OECD also states that social protection measures are ‗[…] investments in people of all ages

[that] […] have a clear gender dimension.‘

UN (2000): ‗[…] a set of public and private policies and programmes undertaken by societies in

response to various contingencies to offset the absence or substantial reduction of income from

work; to provide assistance for families with children as well as provide people with health care

and housing. This definition is not exhaustive; it basically serves as a starting point of the

analysis […] as well as a means to facilitate this analysis.‘

Source: Zhang, Thelen and Rao (2012, p.).

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seoulsppaperfinaldraft25oct2012-121105201408-phpapp01/85/Social-Protection-Overview-65-320.jpg)