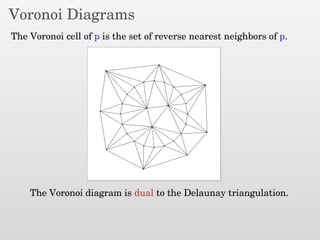

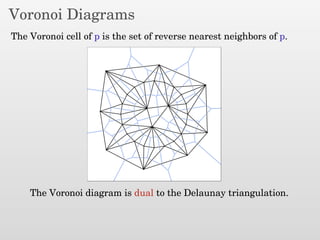

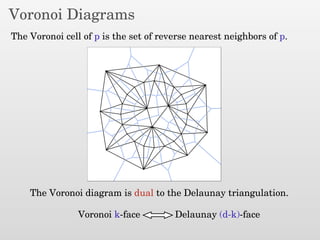

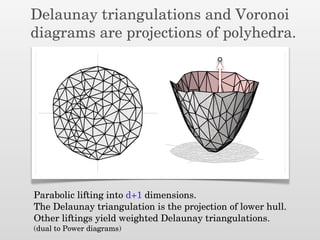

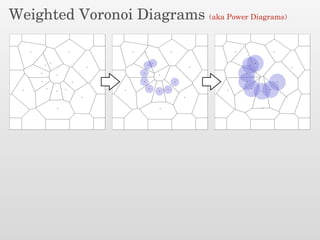

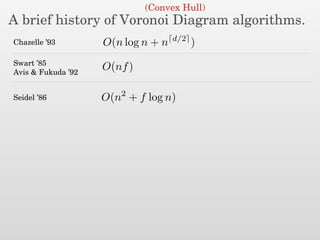

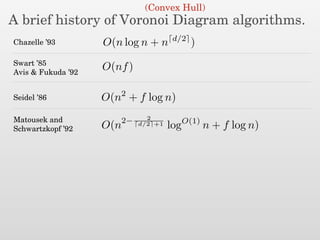

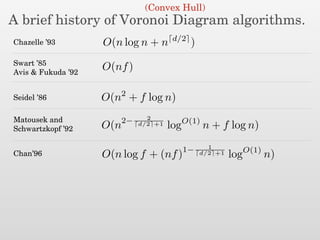

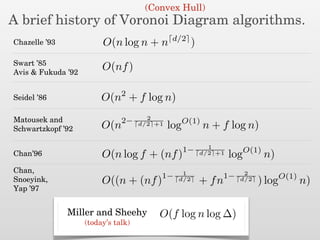

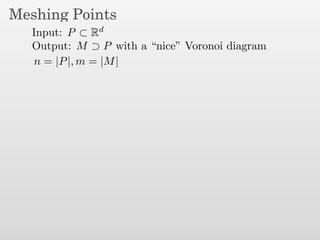

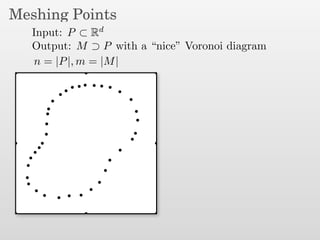

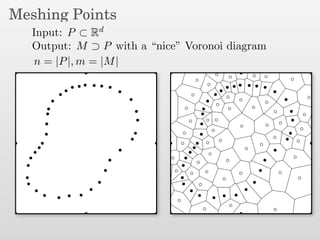

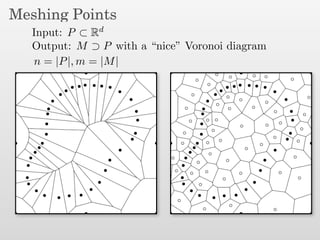

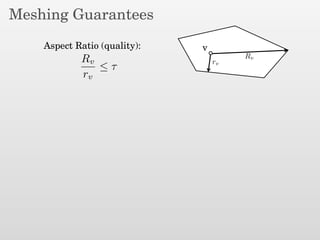

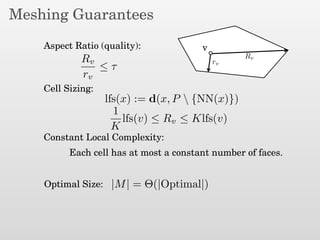

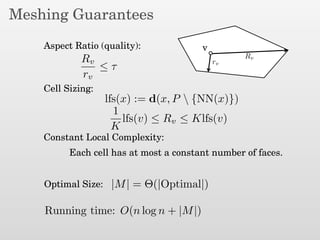

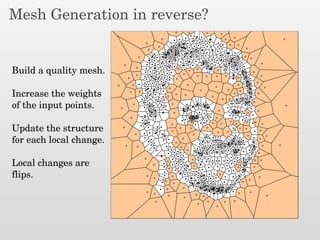

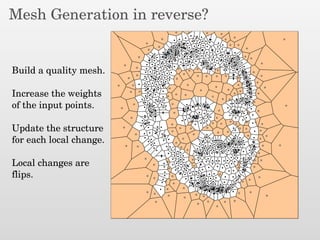

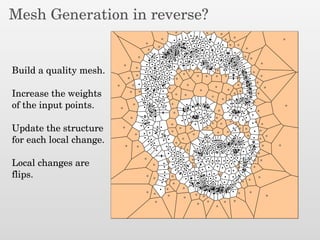

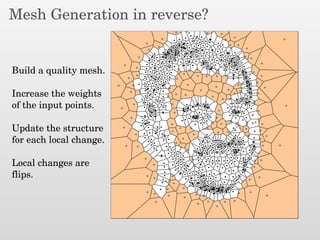

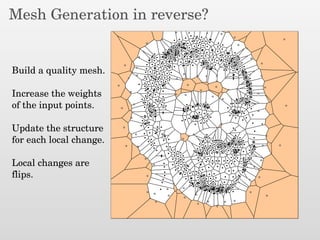

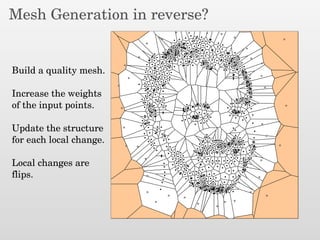

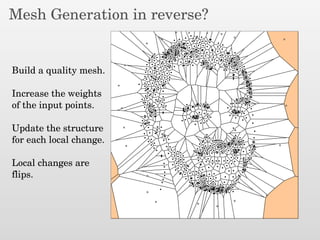

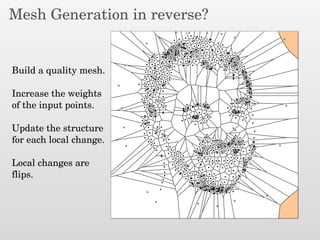

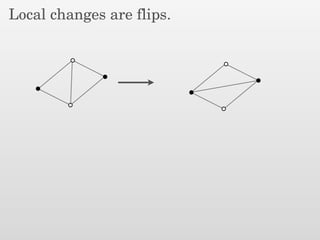

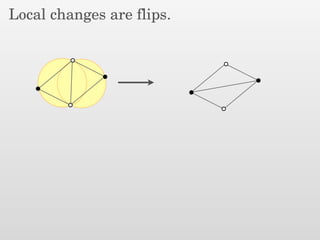

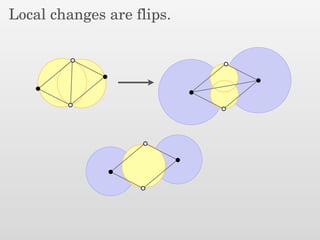

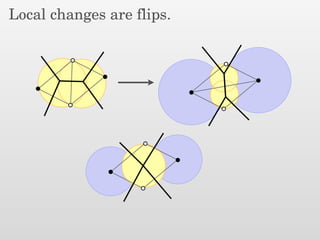

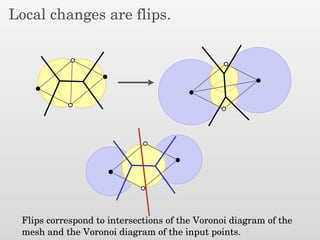

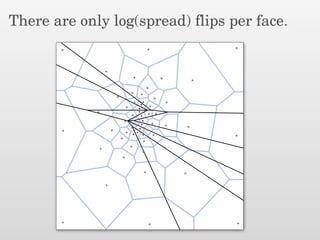

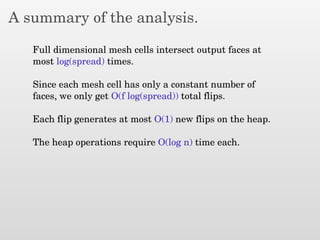

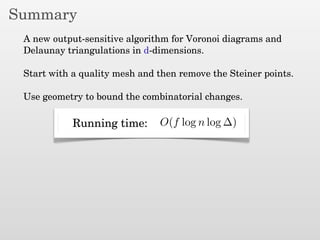

The document presents a new output-sensitive algorithm for constructing Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay triangulations in d-dimensions, emphasizing a method that begins with a quality mesh and subsequently removes Steiner points. It discusses the relationship between Voronoi diagrams and Delaunay triangulations, as well as various techniques employed in the algorithm, including maintaining a bounding box and managing local changes through flips. The algorithm achieves a running time of O(f log n log ∆), leveraging geometric properties to control combinatorial changes.