1. Shock is defined as a state where the delivery of oxygen to tissues is inadequate to meet metabolic demands, resulting in cellular dysfunction.

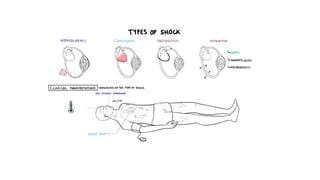

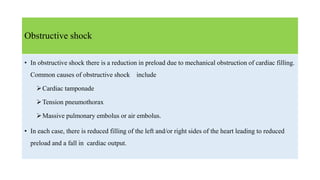

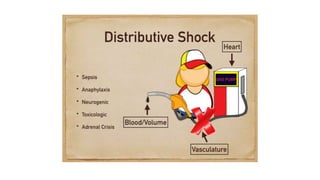

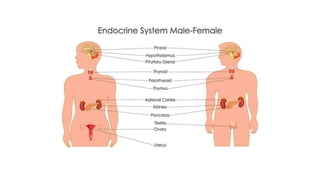

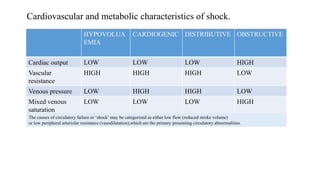

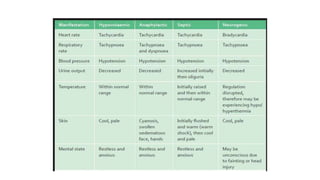

2. Shock is classified into five main types: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, obstructive, distributive, and endocrine.

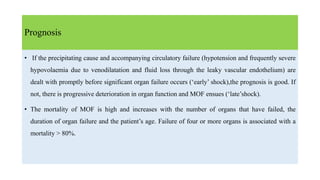

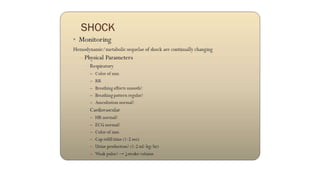

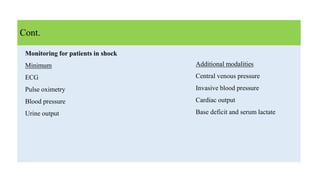

3. Treatment for shock involves rapid fluid resuscitation to restore circulating volume, with vasopressors or inotropes as needed depending on the type of shock. Ongoing monitoring of vital signs and urine output is also critical.