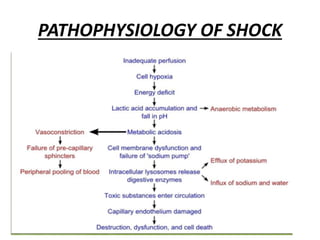

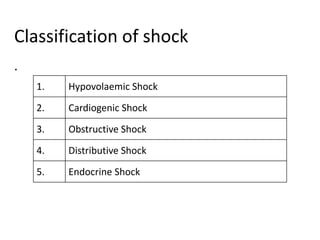

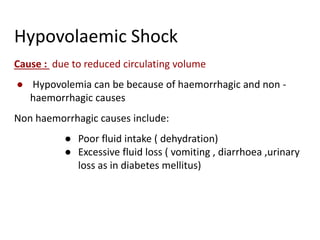

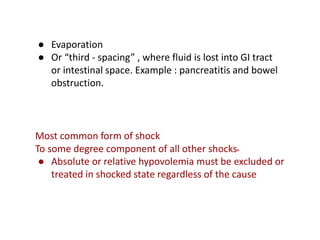

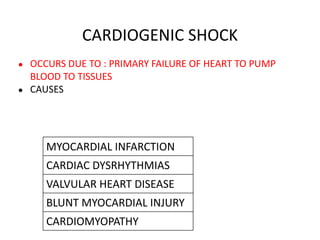

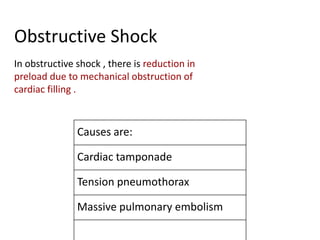

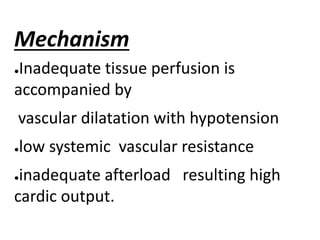

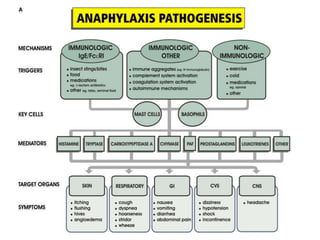

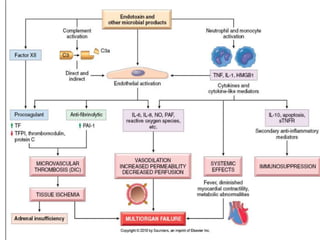

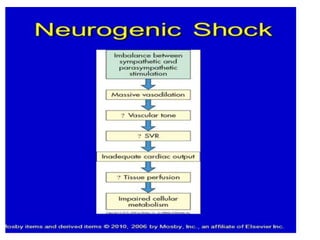

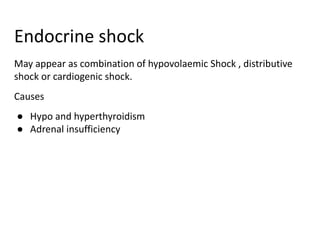

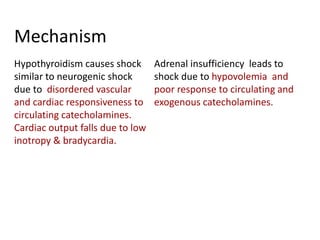

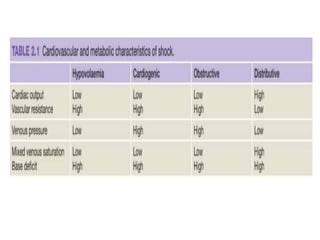

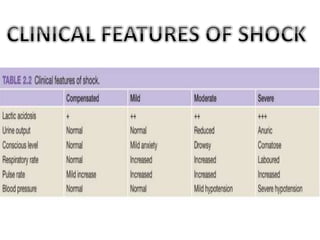

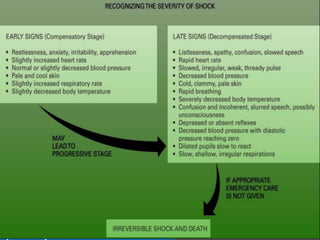

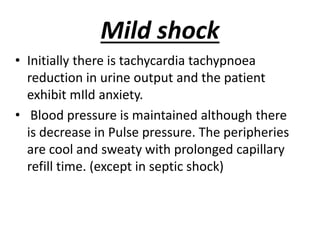

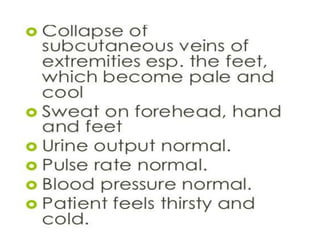

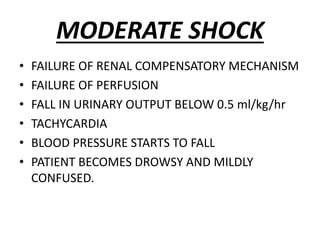

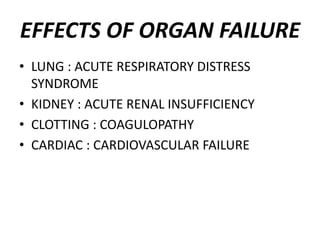

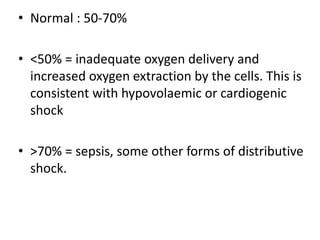

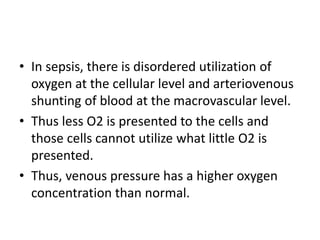

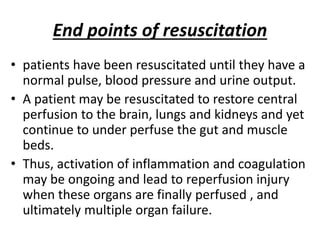

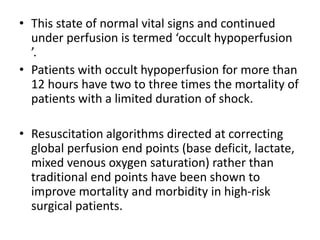

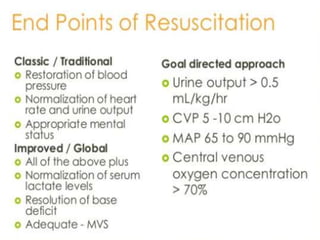

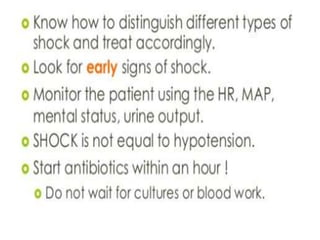

The document discusses shock as a state of inadequate tissue perfusion leading to cellular respiration failure, with various mechanisms classified into types such as hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and distributive shock. It outlines the pathophysiology, consequences, and management strategies for shock, including the importance of early resuscitation and monitoring to prevent organ failure. The document also emphasizes that timely intervention is crucial to reducing mortality and morbidity associated with shock-related complications.