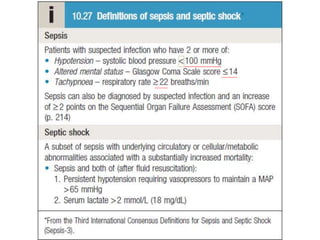

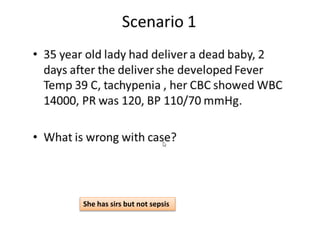

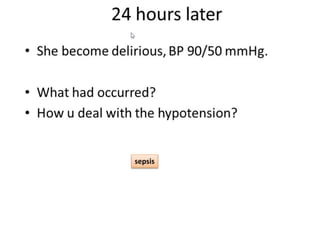

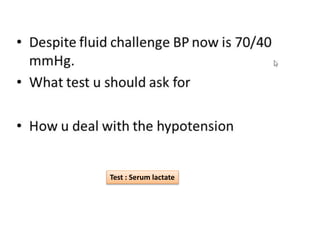

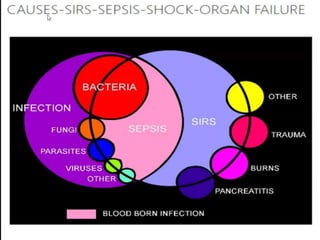

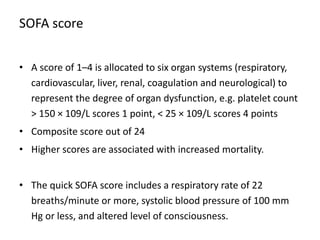

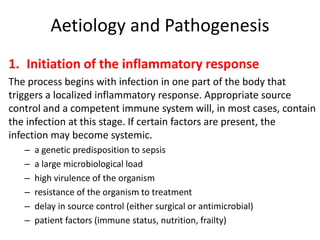

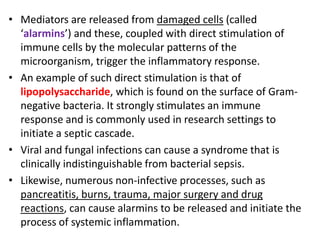

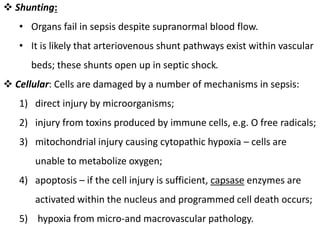

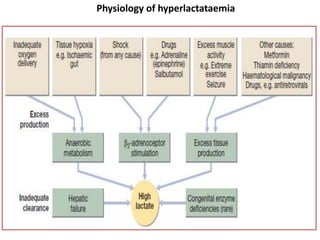

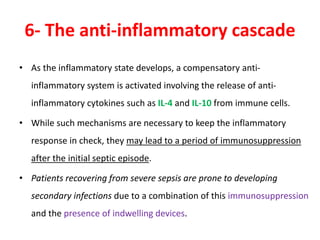

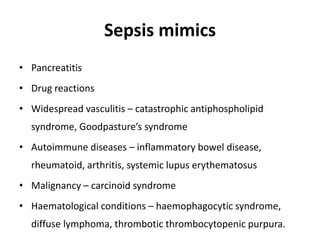

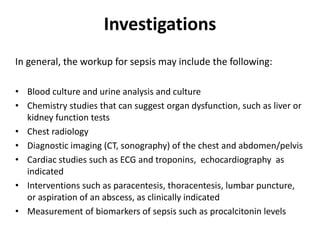

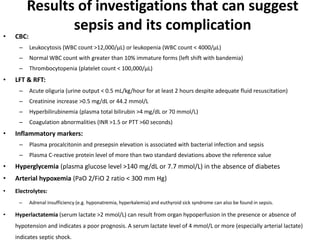

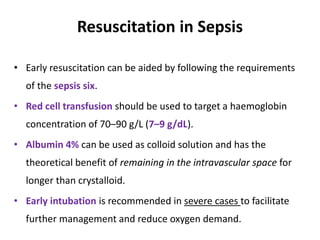

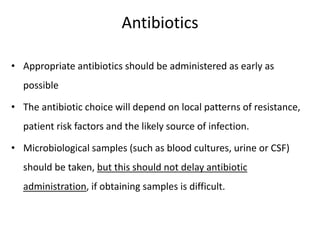

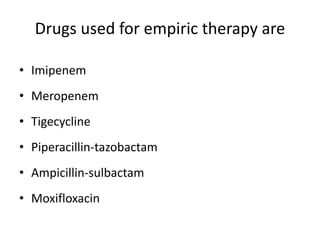

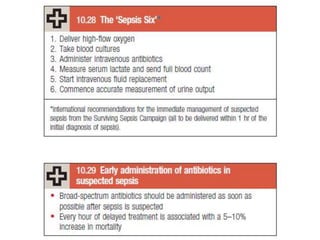

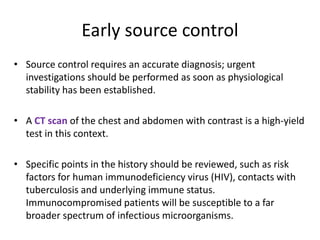

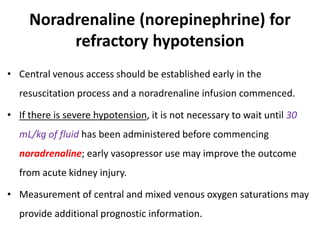

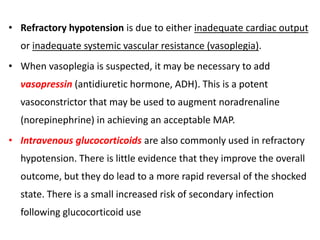

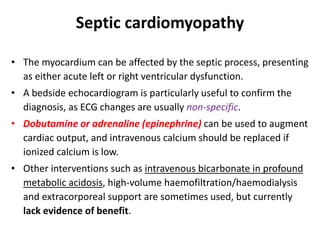

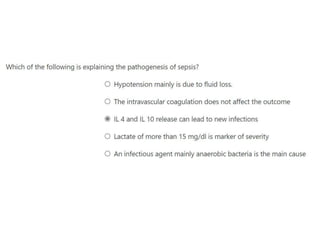

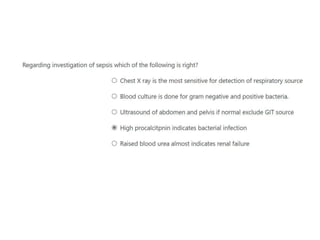

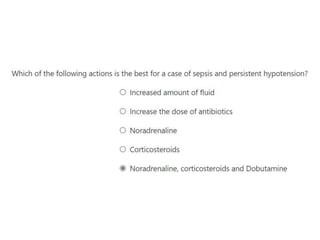

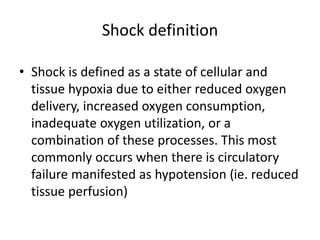

The document discusses sepsis and septic shock. It defines shock and classifies different types including cardiogenic, hypovolemic, anaphylactic, septic, and neurogenic shock. It describes the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria. Non-infective processes like trauma or surgery can also cause SIRS. Investigations for sepsis may include blood cultures, imaging, and biomarkers like procalcitonin. Positive findings include leukocytosis/leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, organ dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and hyperlactatemia. Early goal-directed resuscitation including antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and inotropes can improve outcomes in septic shock.

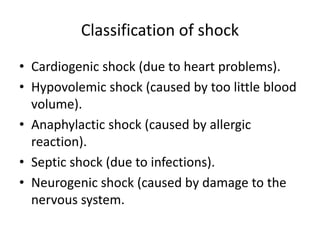

![Systemic inflammatory reaction

syndrome (SIRS)

Clinically, the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) is the

occurrence of at least two of the following criteria:

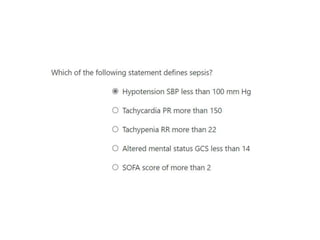

1. Fever of more than 38°C (100.4°F) or less than 36°C (96.8°F)

2. Heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute

3. Respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute or arterial

carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2) of less than 32 mm Hg

4. Abnormal white blood cell count (>12,000/µL or < 4,000/µL or

>10% immature [band] forms)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sepsis-210715133321/85/Sepsis-4-320.jpg)