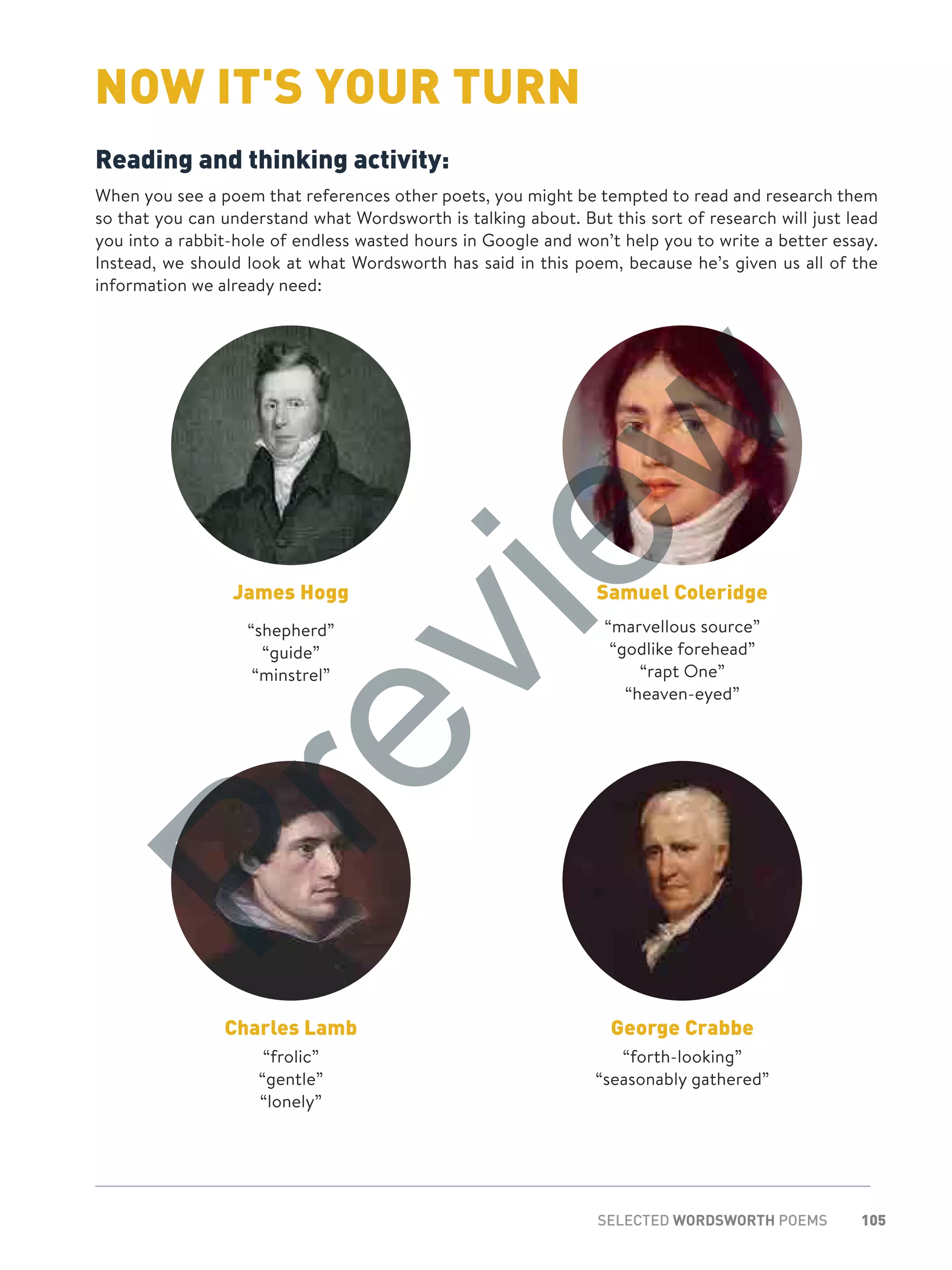

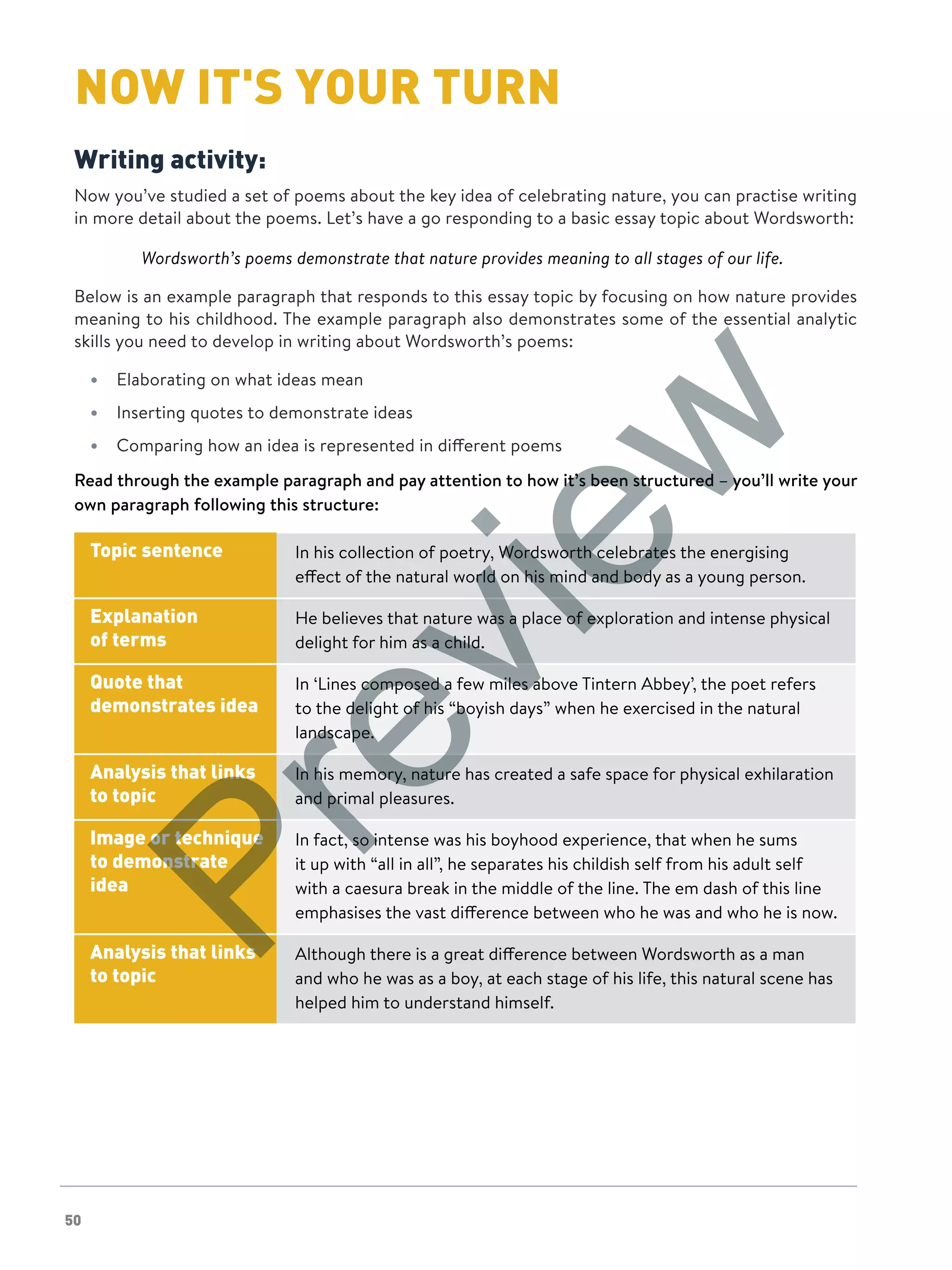

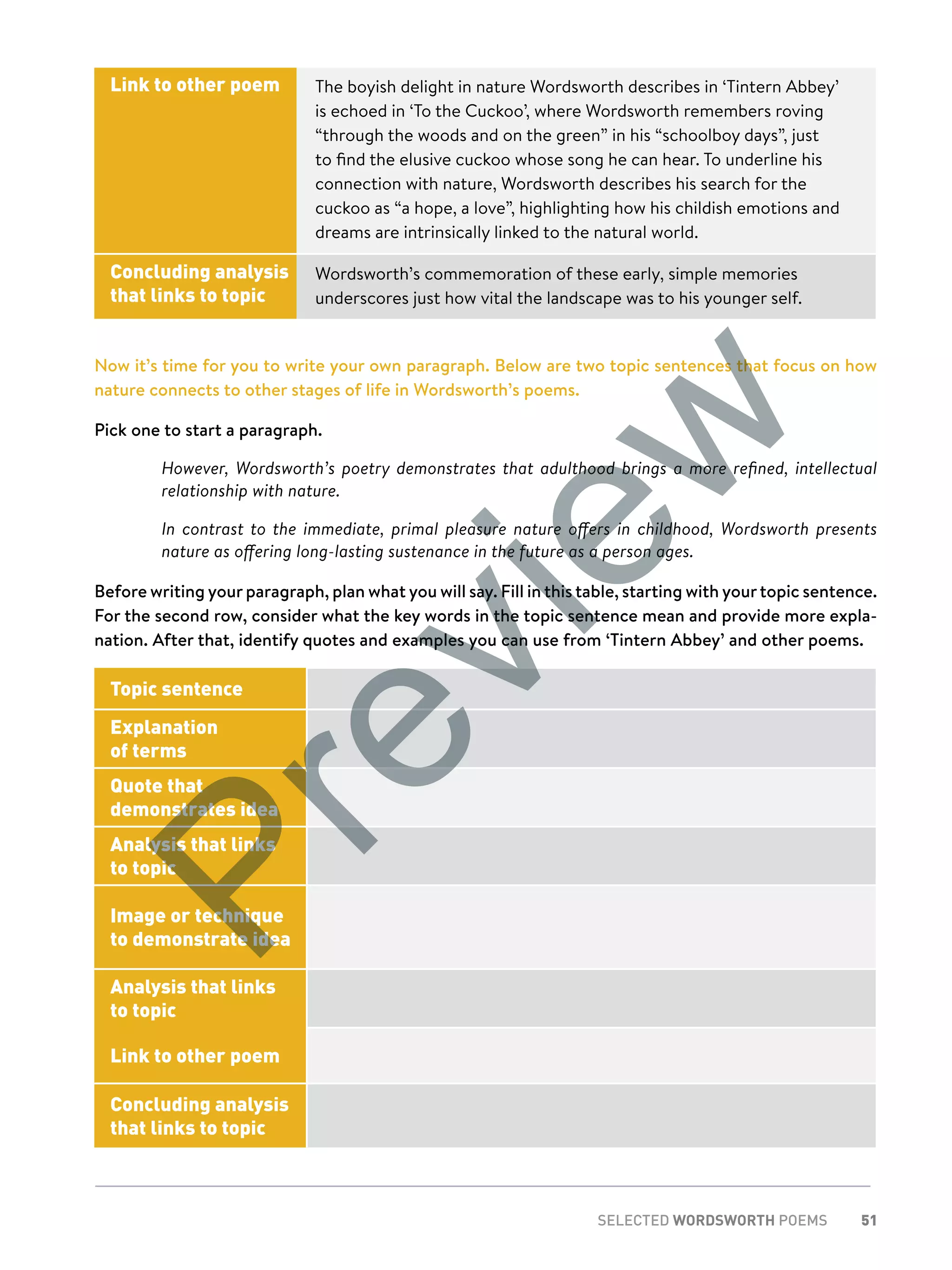

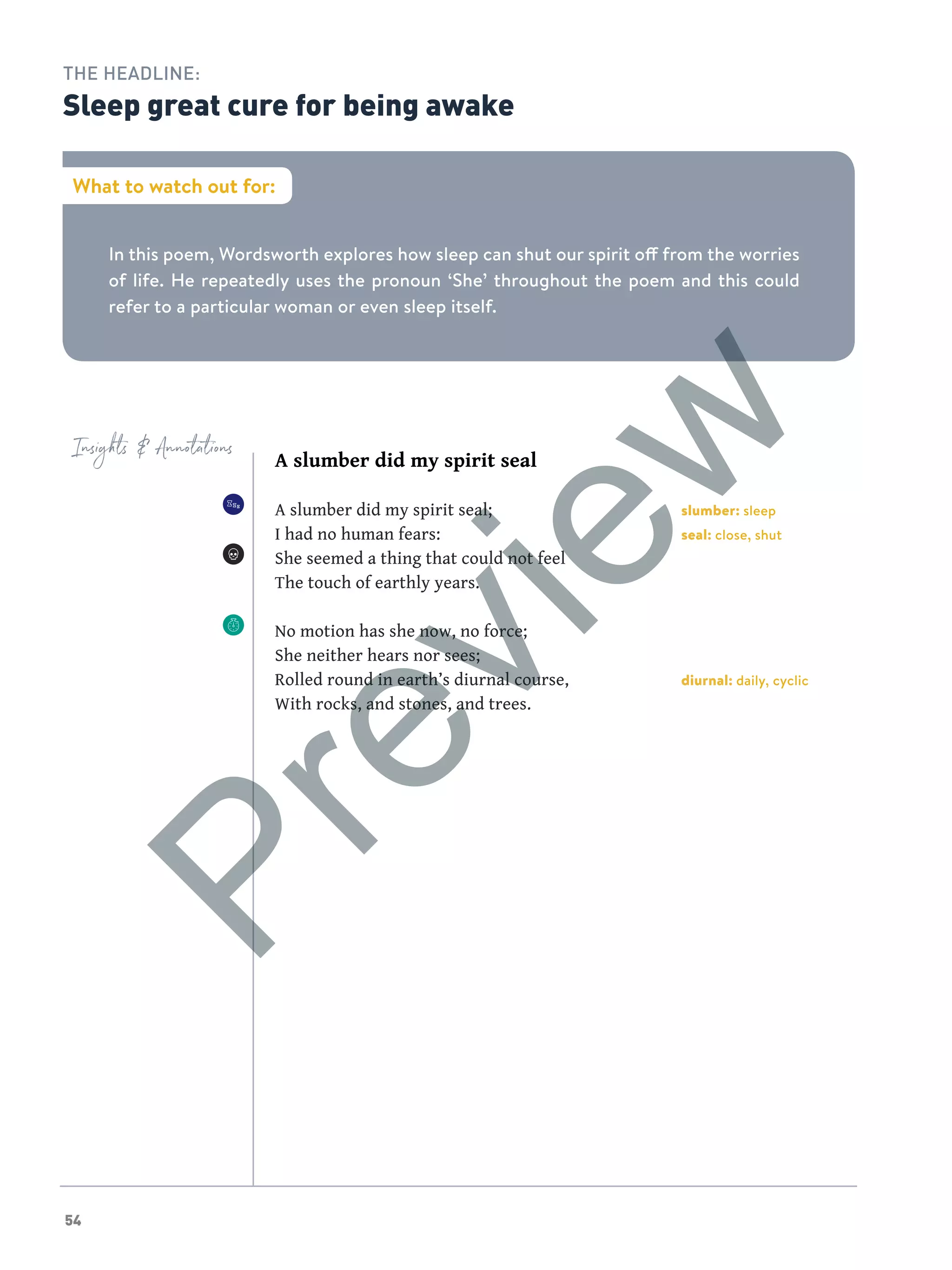

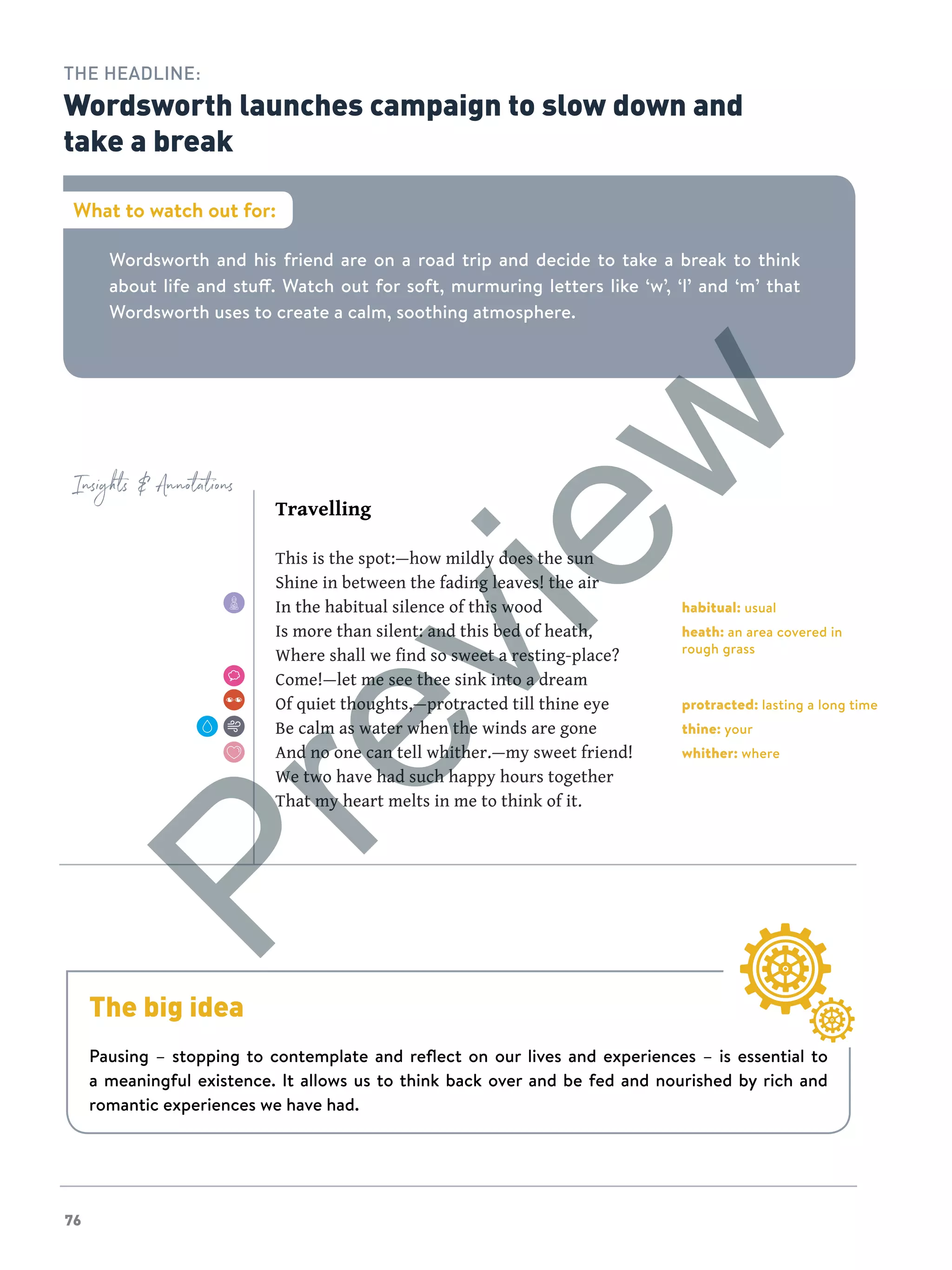

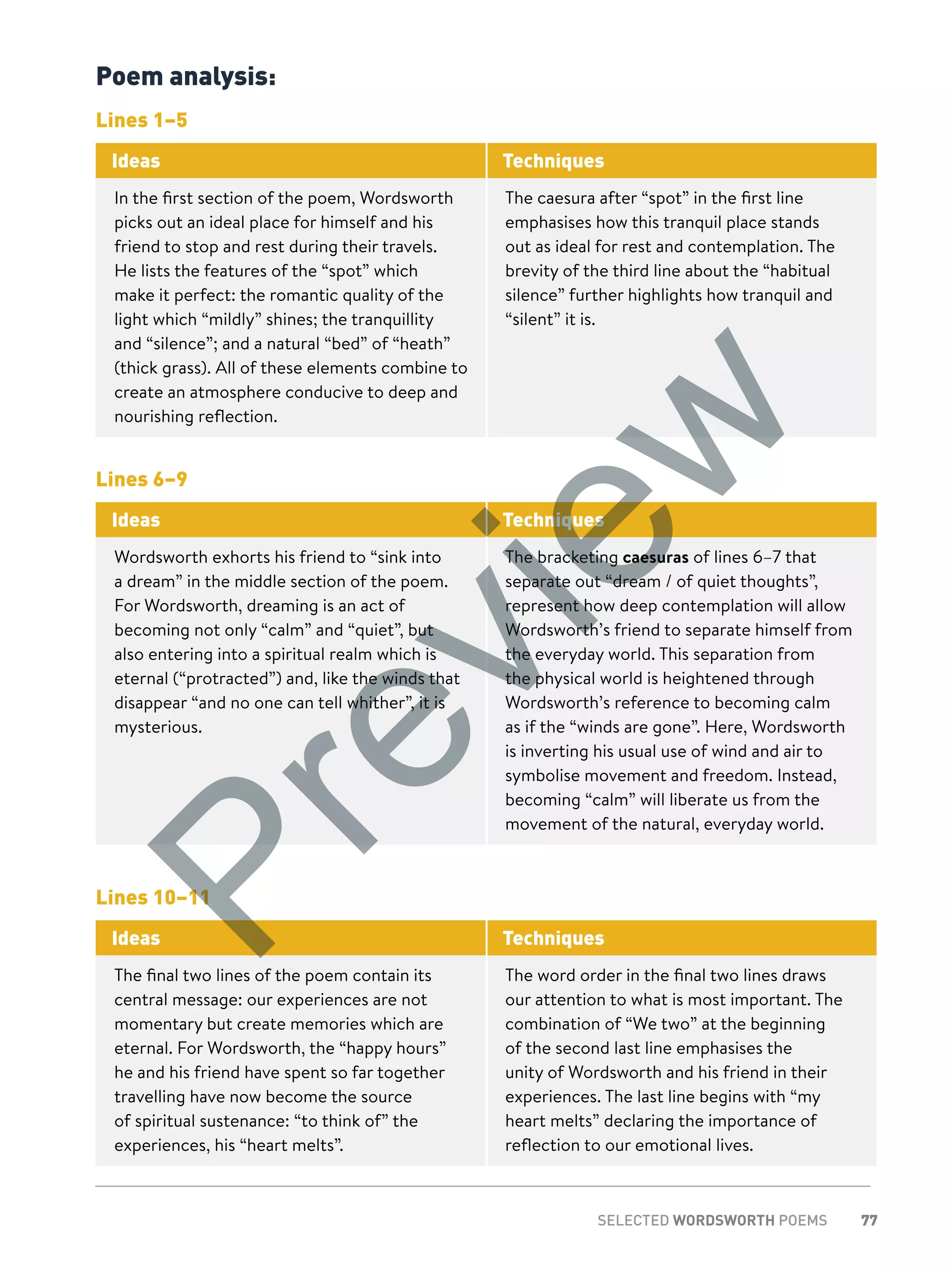

The document is a guide to reading and analyzing selected poems by Wordsworth, focusing on key romantic themes such as the connection to nature, the inevitability of death, and the importance of reflection and art. It explains how to approach poetry through various levels of analysis and outlines the different poetic forms and techniques used by Wordsworth. The guide emphasizes the value of understanding romantic ideals and the significance of emotional expression in poetry.

![32

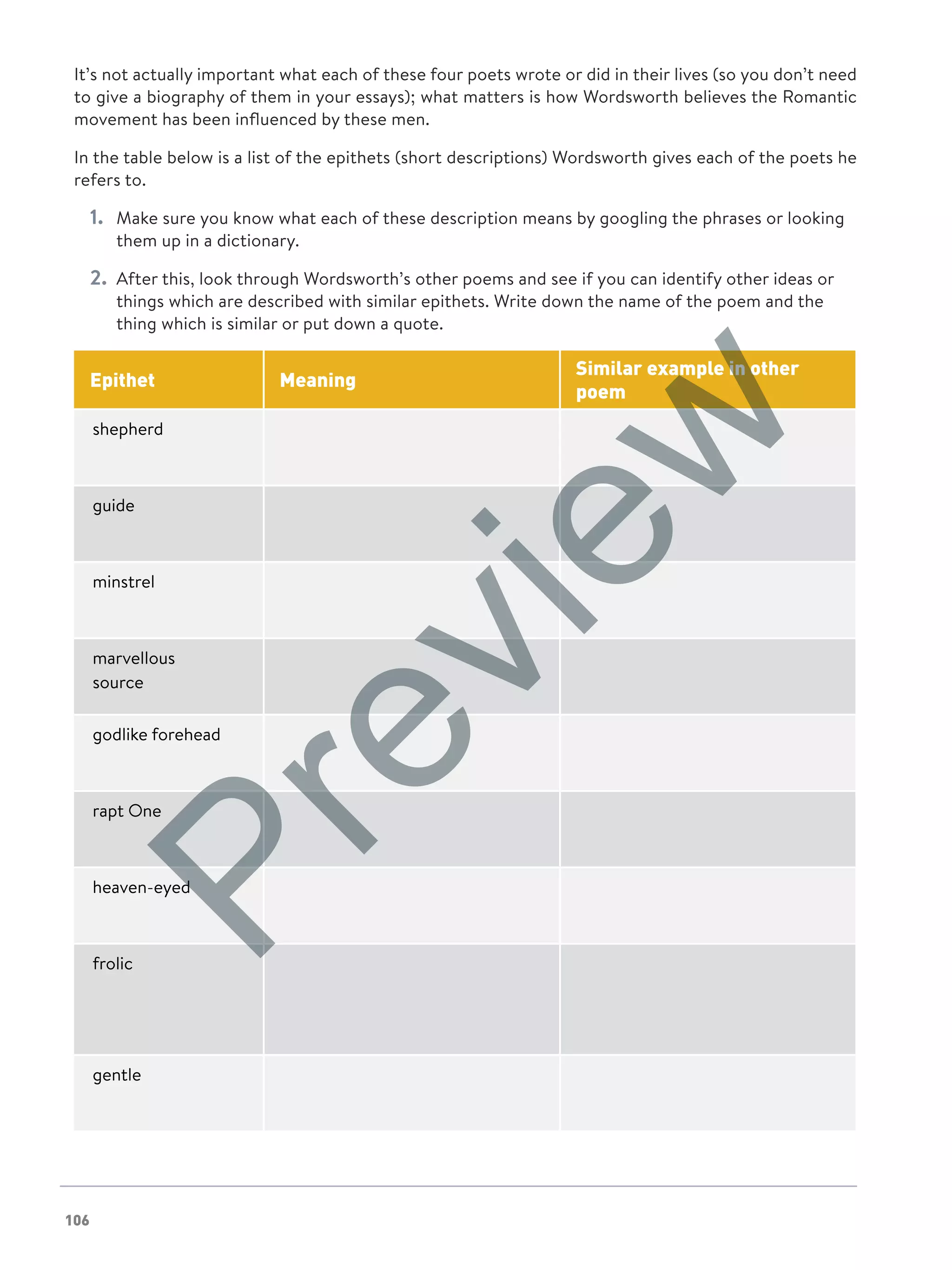

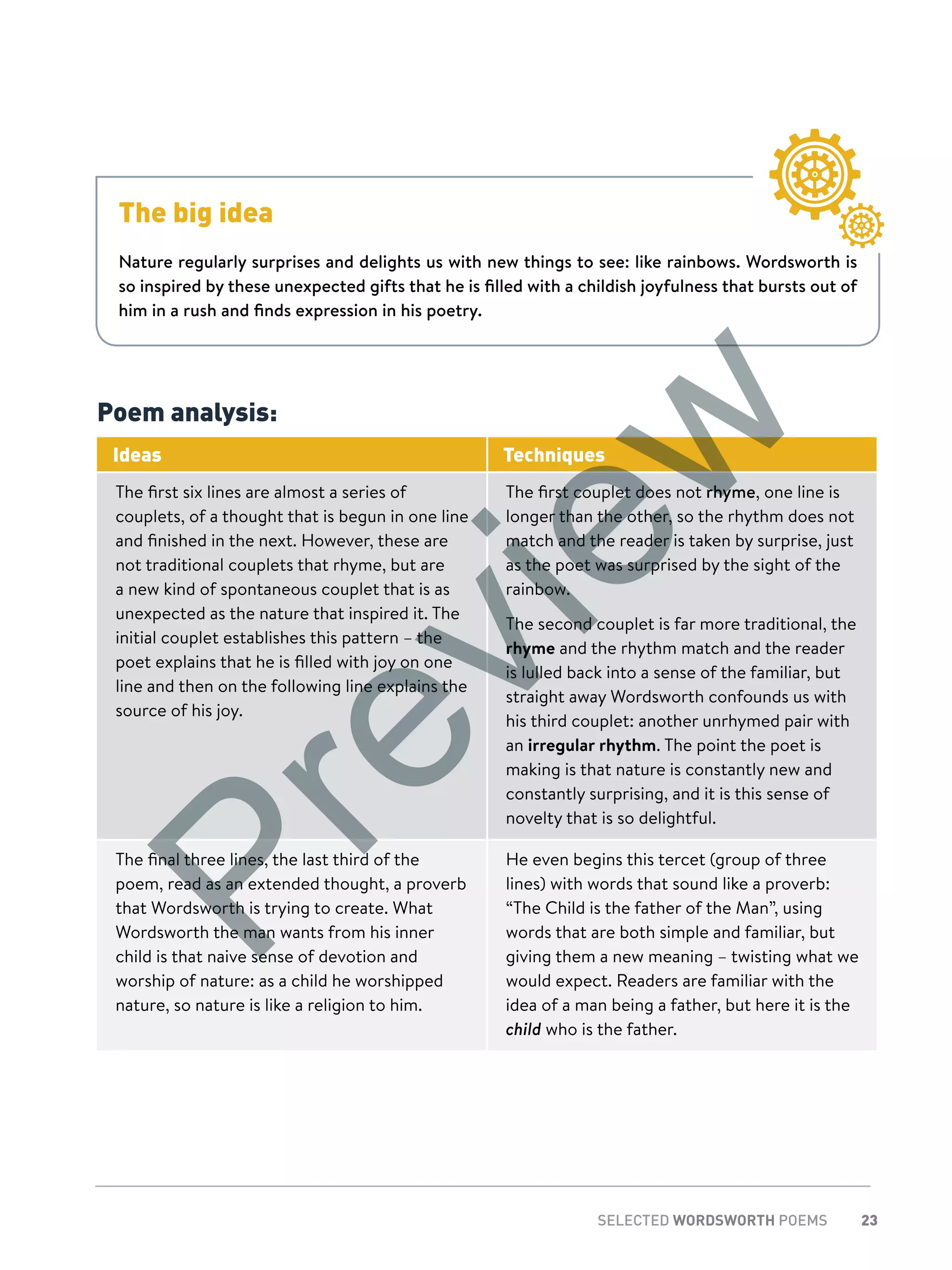

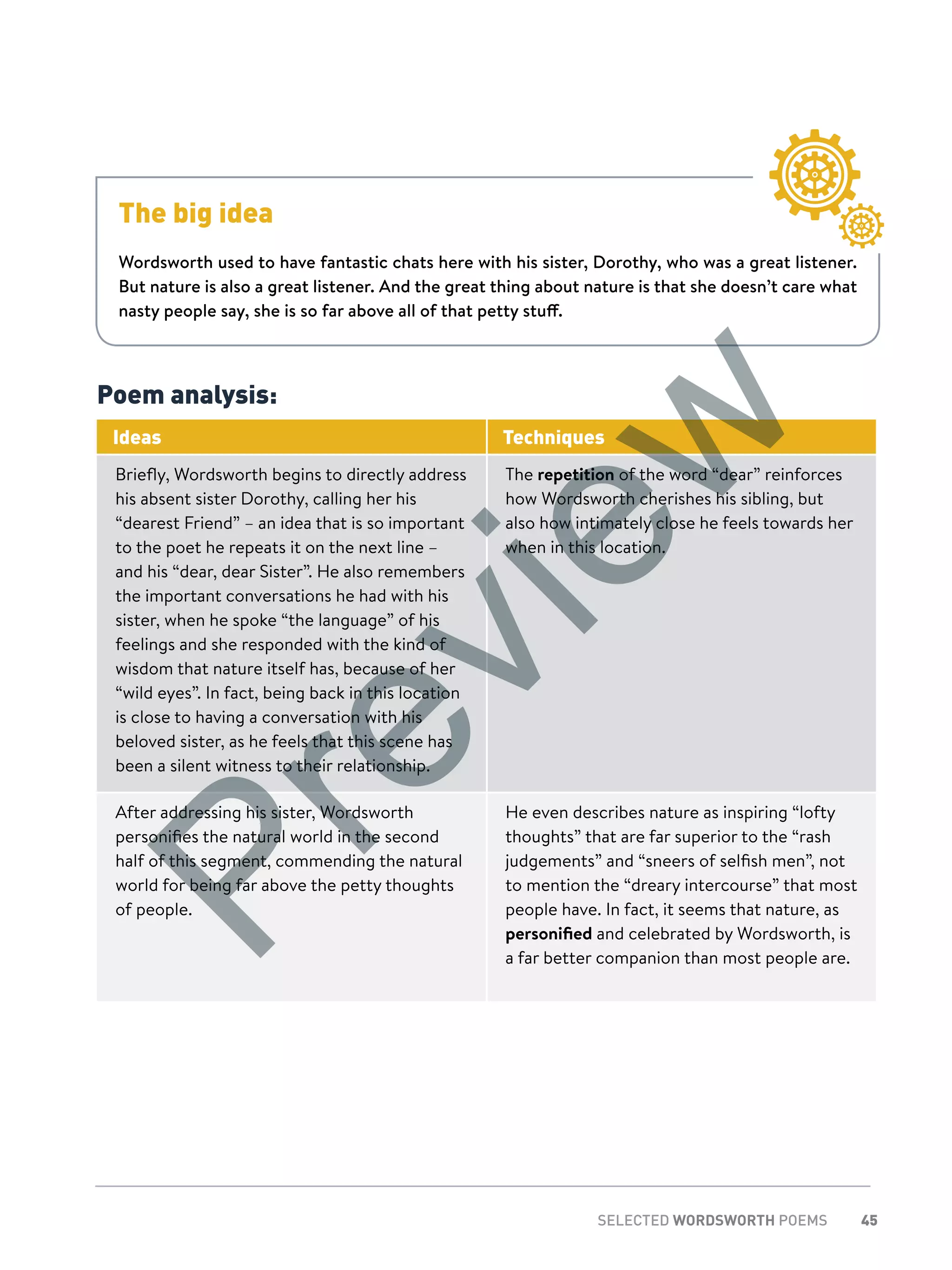

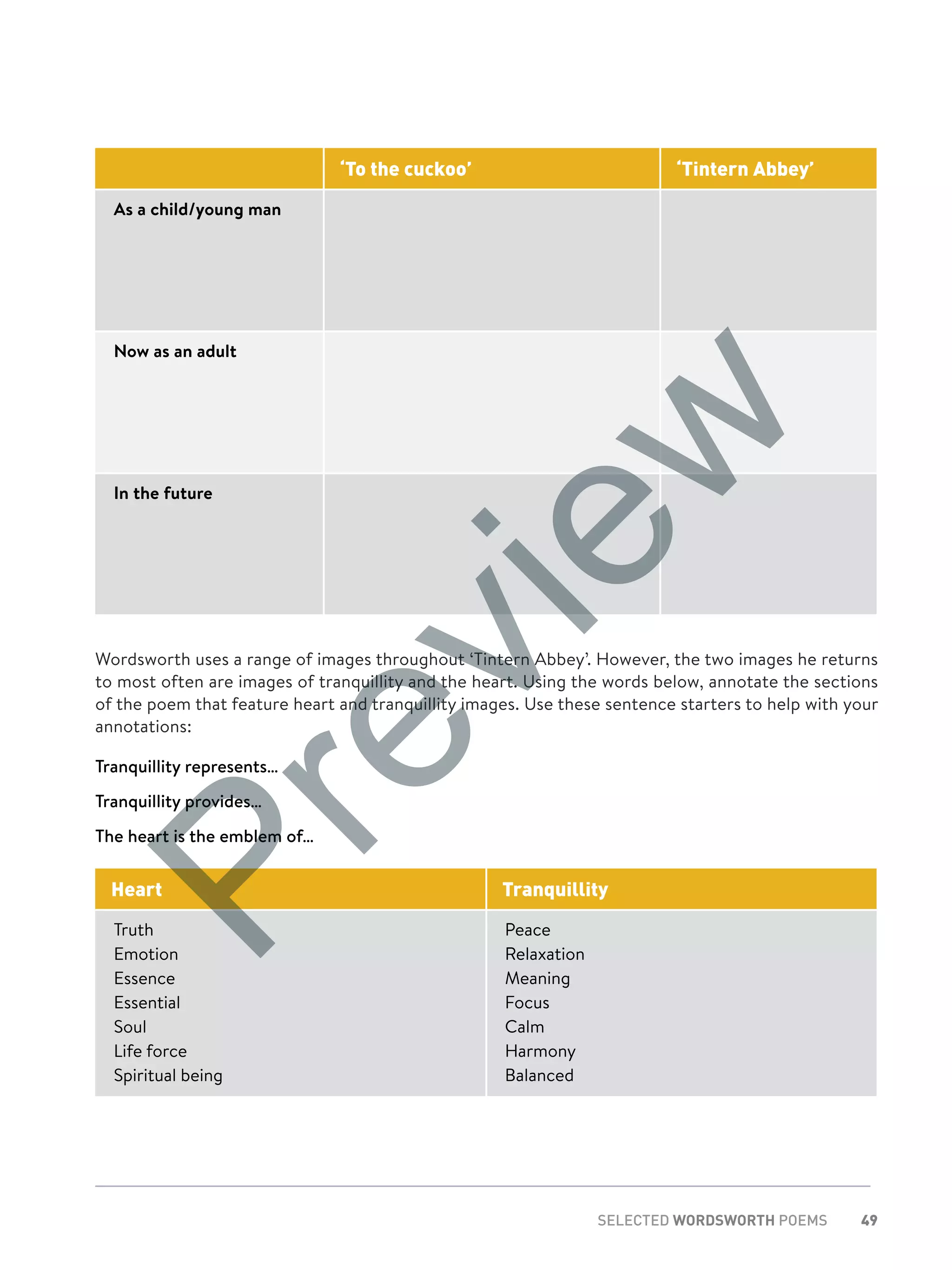

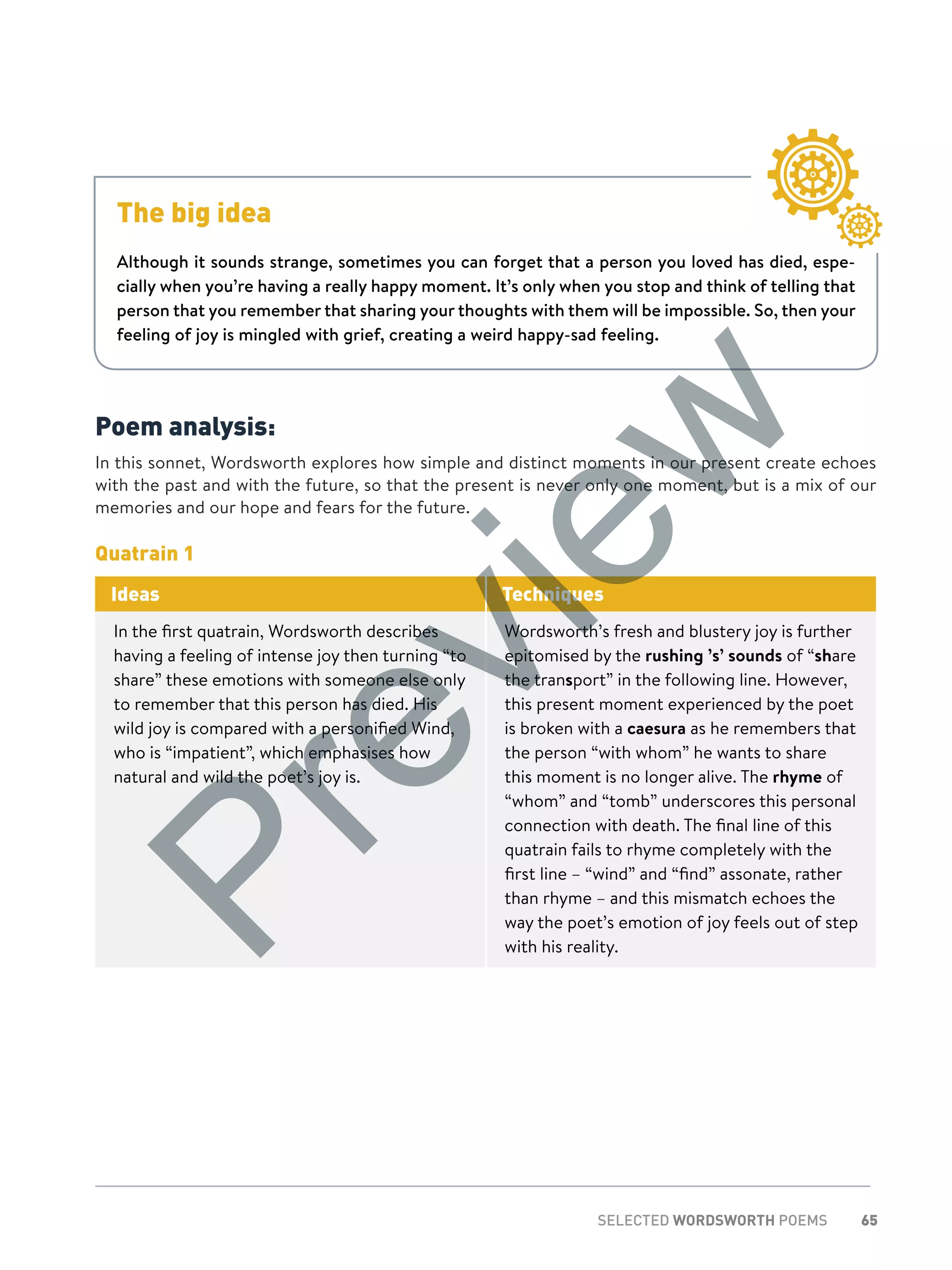

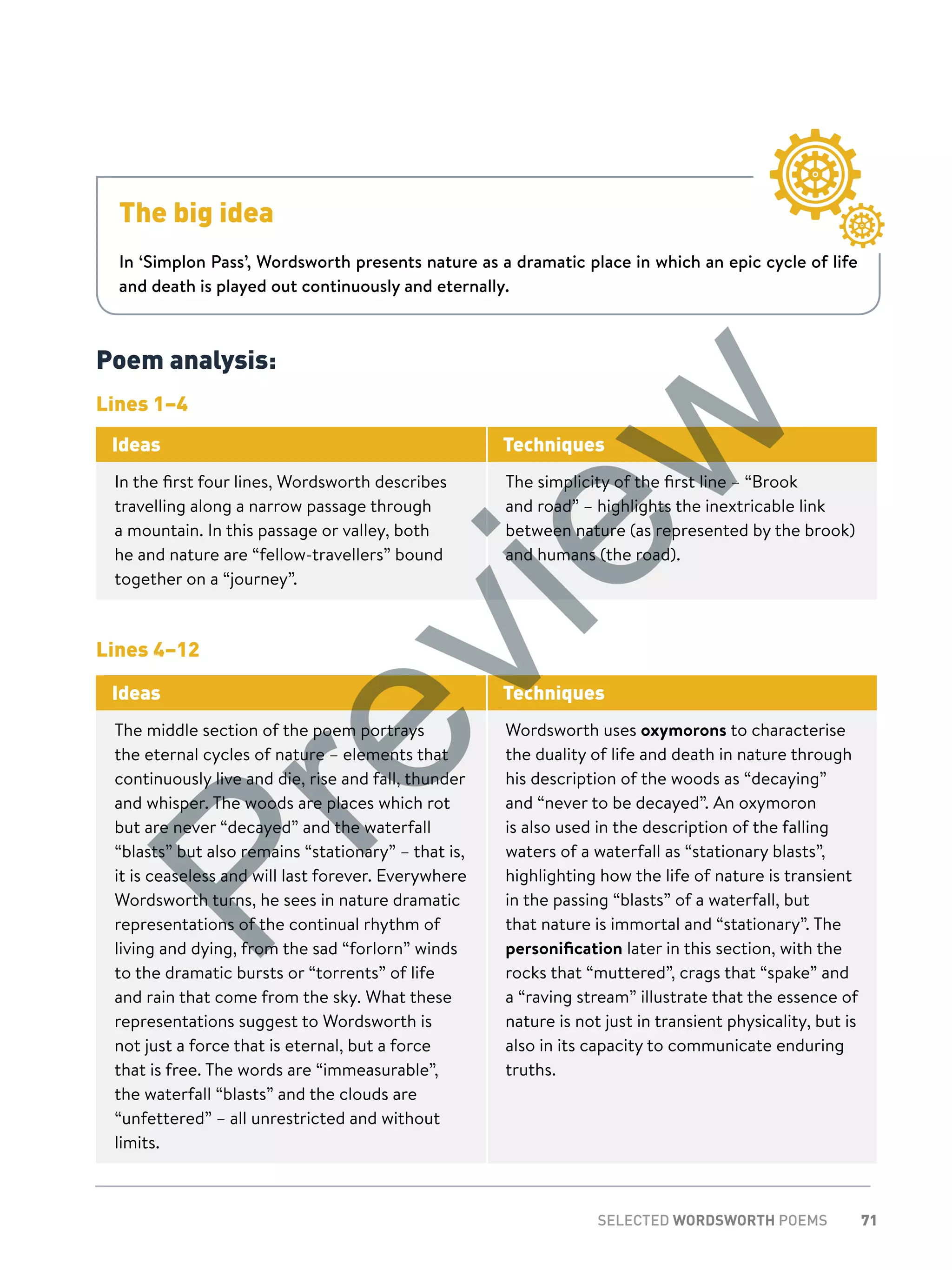

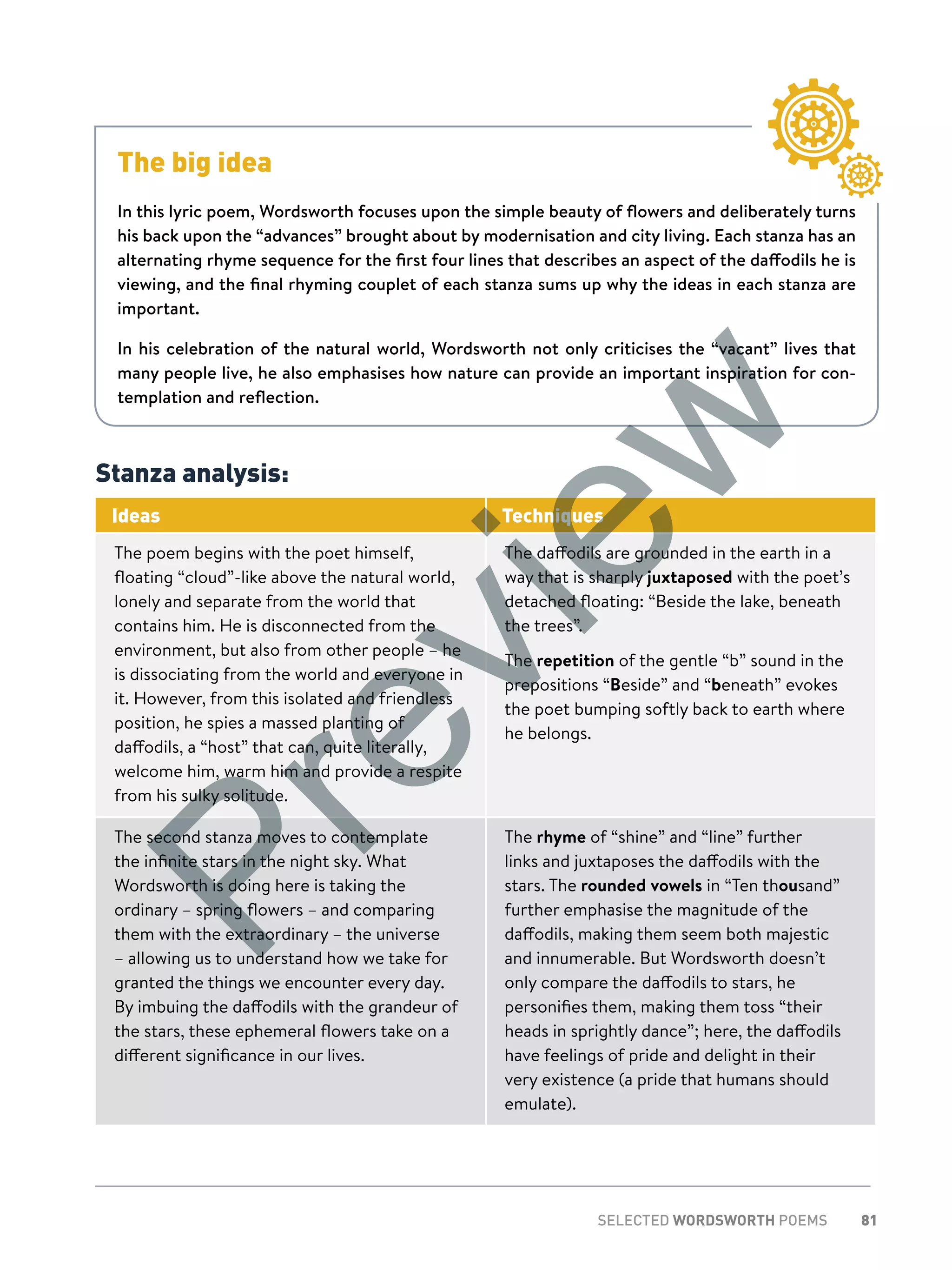

Ideas Techniques

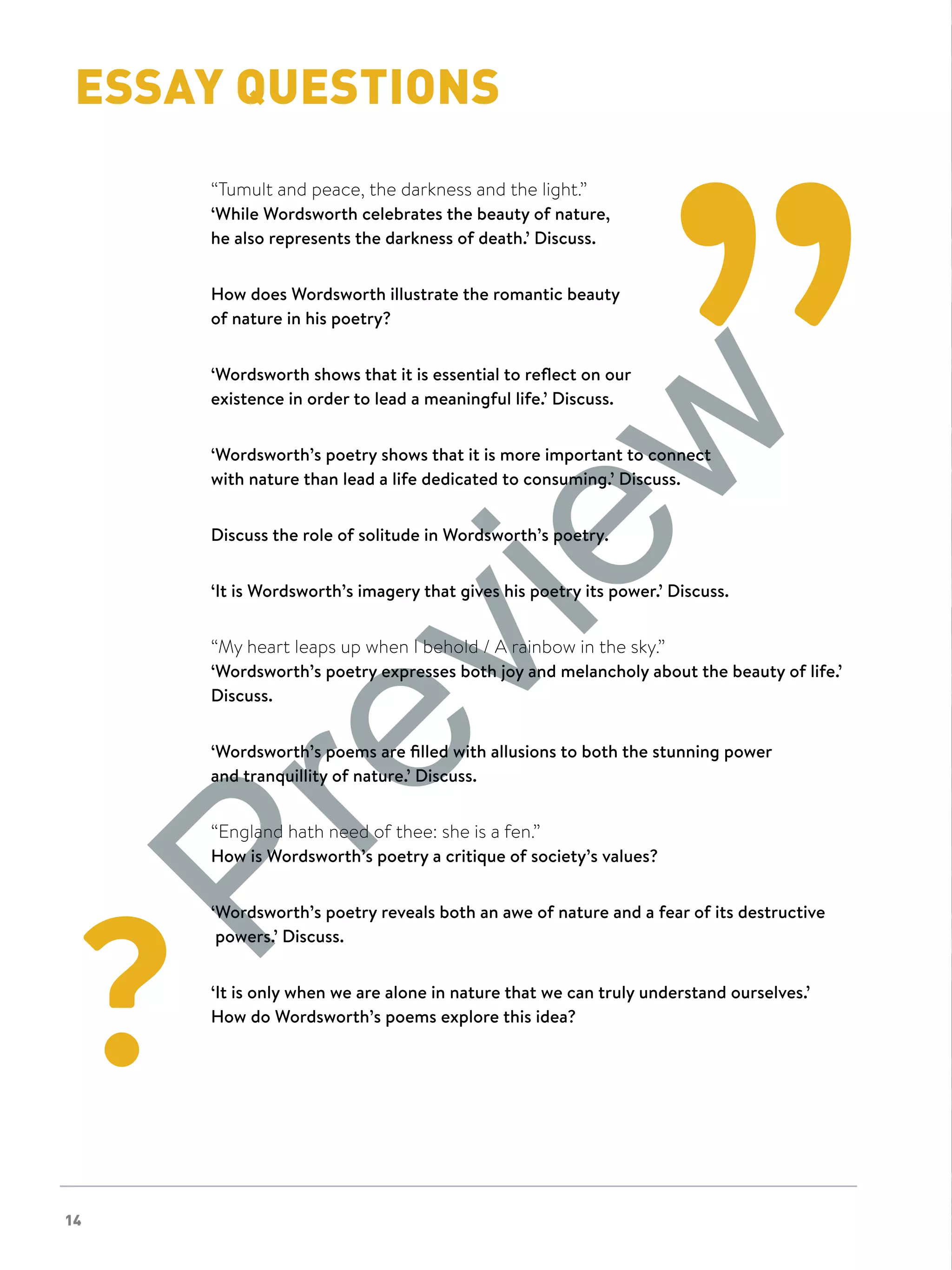

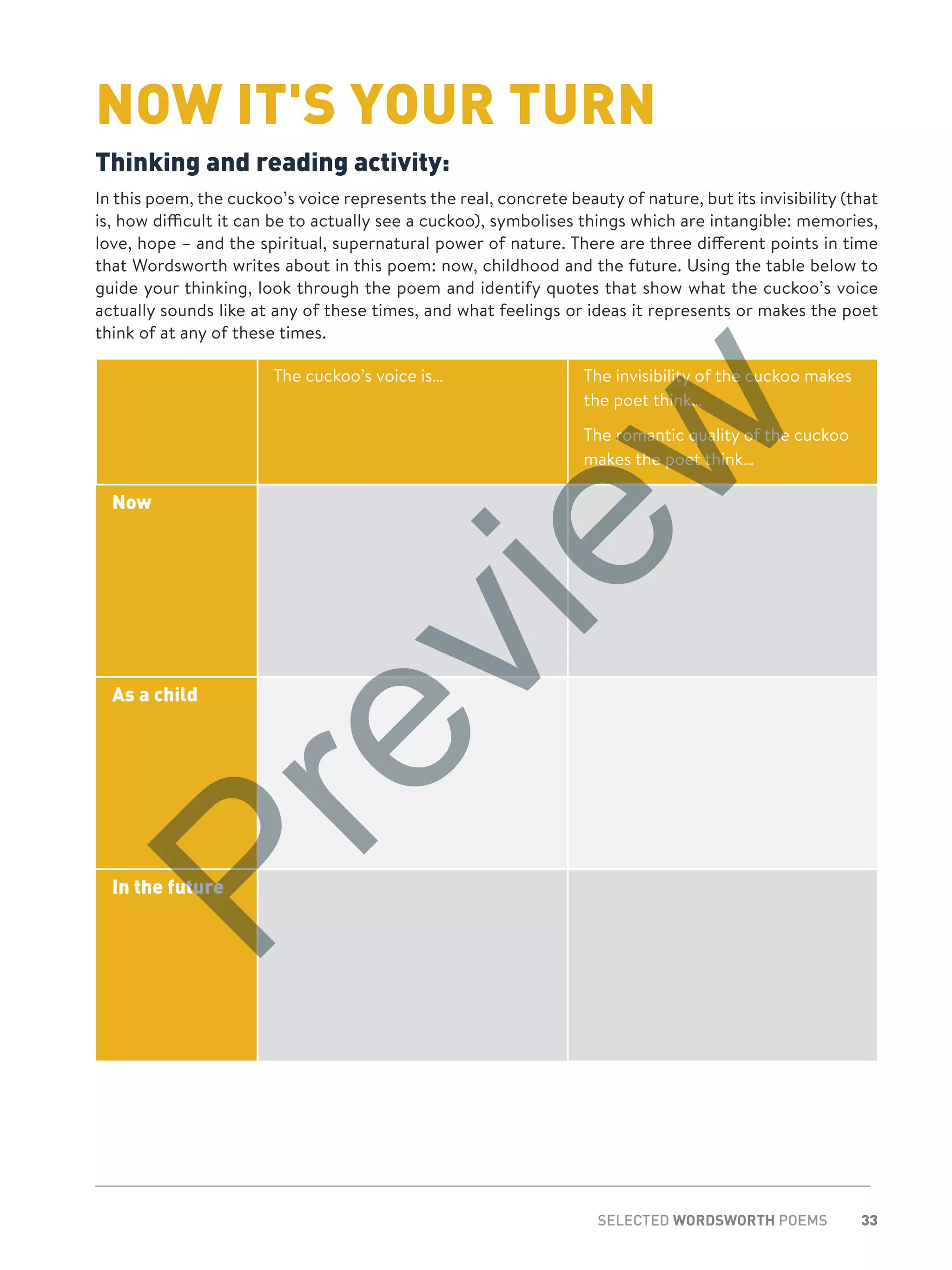

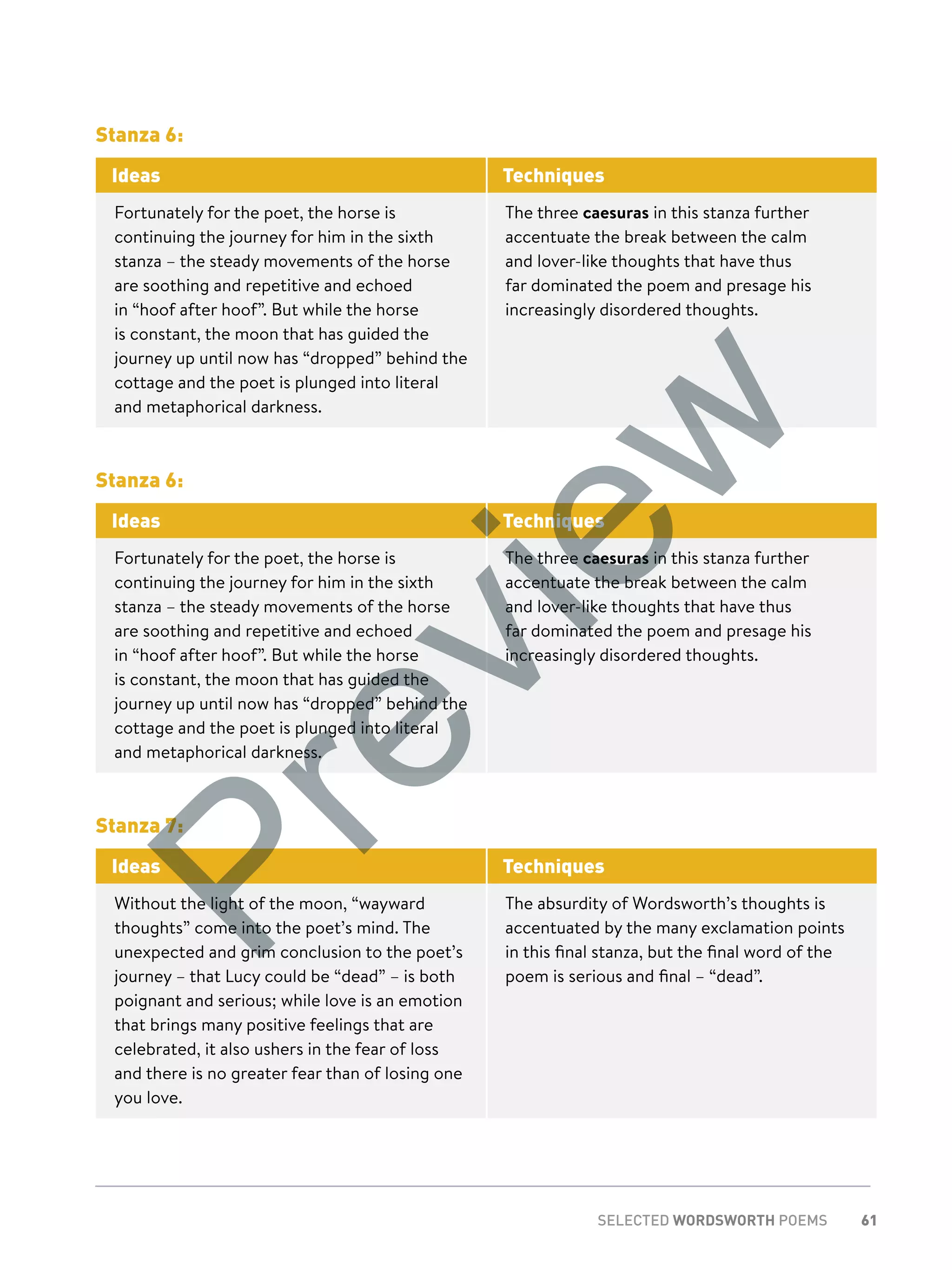

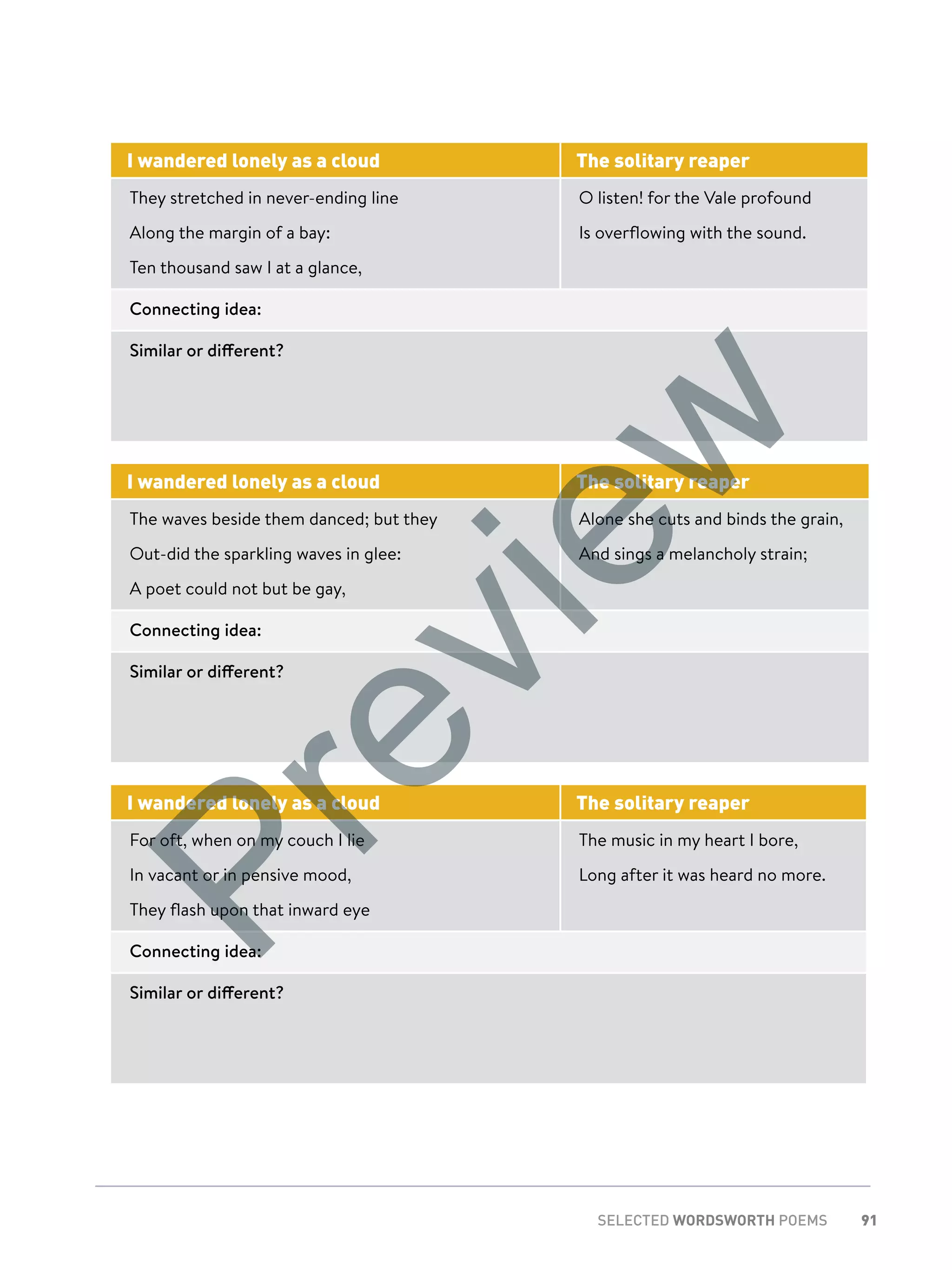

The poet delves further into his imagination

in the third and fourth stanzas, connecting

the sound of the cuckoo with the sound of

time; just as the wooden cuckoo can keep time

within a cuckoo clock, this real bird can bring

the sense of “visionary hours” to Wordsworth.

The poet also imagines that the bird is singing

romantically of “sunshine and flowers”,

creating a sense of shared joy in beauty

between the two of them.

In the fourth stanza, the connection to time

is strengthened as the poet refers to “thrice”,

which follows his reference to “twofold” from

earlier in the poem – it is as though this real

cuckoo is marking time, just as the wooden

birds in a clock do. And so here the bird is

representative of the elusive nature of time,

“an invisible thing” that marks our lives. Time

is also made more concrete because the poet

points out that the cuckoo is a herald of spring

and so, in its own way, does actually mark time

– it’s just that the real cuckoo calls out the

passing of seasons, not hours.

In the fifth and sixth stanzas, the poet moves

backwards through memories to when he

was a “schoolboy” and here he conjures the

searching and yearning that are so much a part

of childhood. In these stanzas, the boy poet

“look[s] a thousand ways” and “longed for”

things he cannot see.

He emphasises this stilted searching in the

final line of the fifth stanza, with its two

caesuras that highlight the multiple directions

of his childish gaze. It is as though the cuckoo

represents all of his youthful hopes and dreams

and all of the discoveries of adulthood that lie

ahead of him.

In closing his poem, Wordsworth refers to the

future, to the pleasure that will come to him

when he listens to the cuckoo again. And here

in this future are evocations of the past: “that

golden time”, since the future is made even

more pleasurable with references to the past.

However, the future is unknowable,

“unsubstantial, faery”, just as the cuckoo’s

voice is. Because the cuckoo can represent the

past, the present, the spring, the future and

time itself, it is an object of wonder and awe

for Wordsworth and he articulates all of these

feelings in this ode.

Preview](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectedwordsworthpoems-preview-191209213923/75/Selected-Wordsworth-Poems-How-to-read-them-understand-them-and-write-truly-insightful-analyses-on-them-32-2048.jpg)

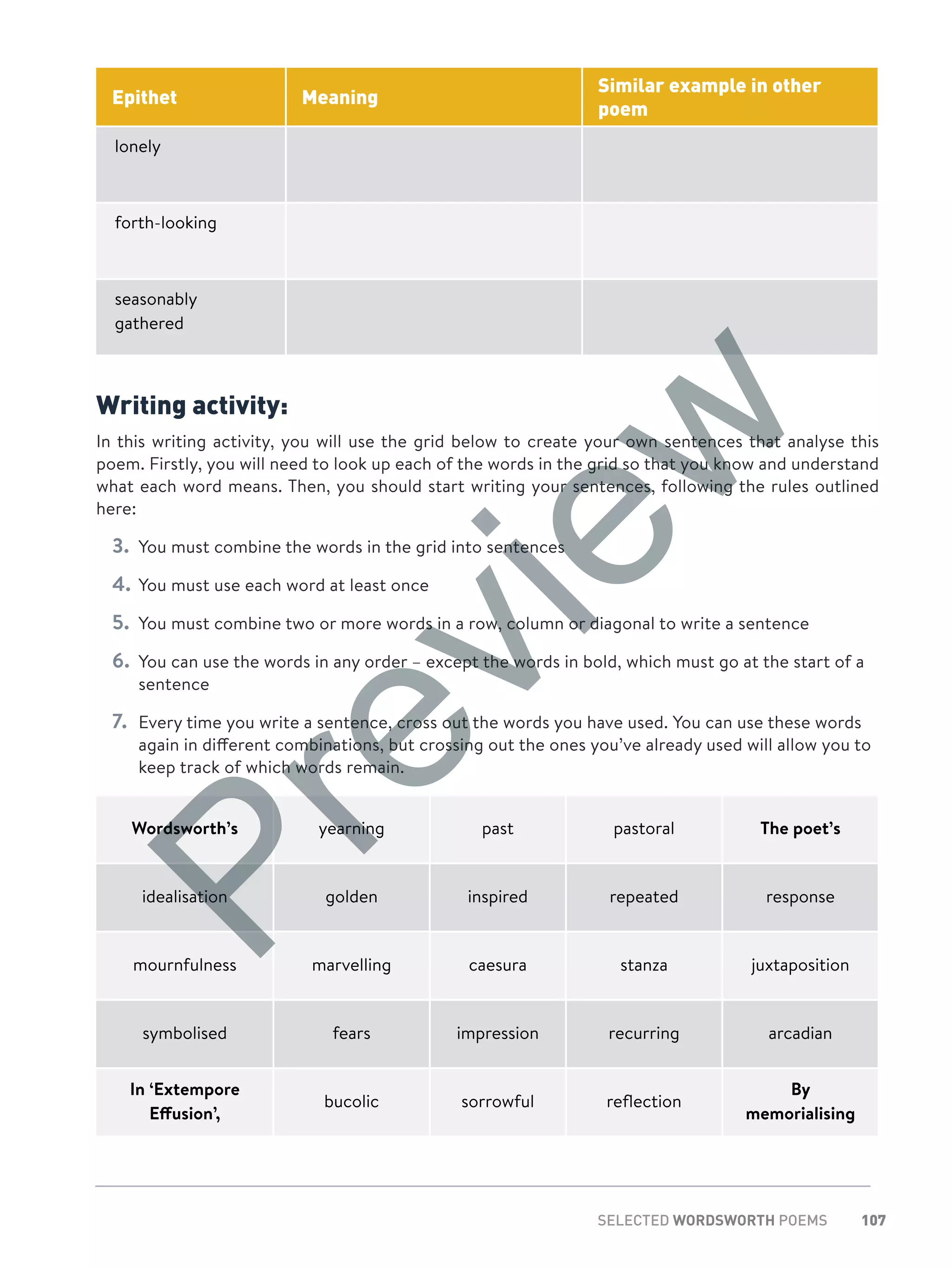

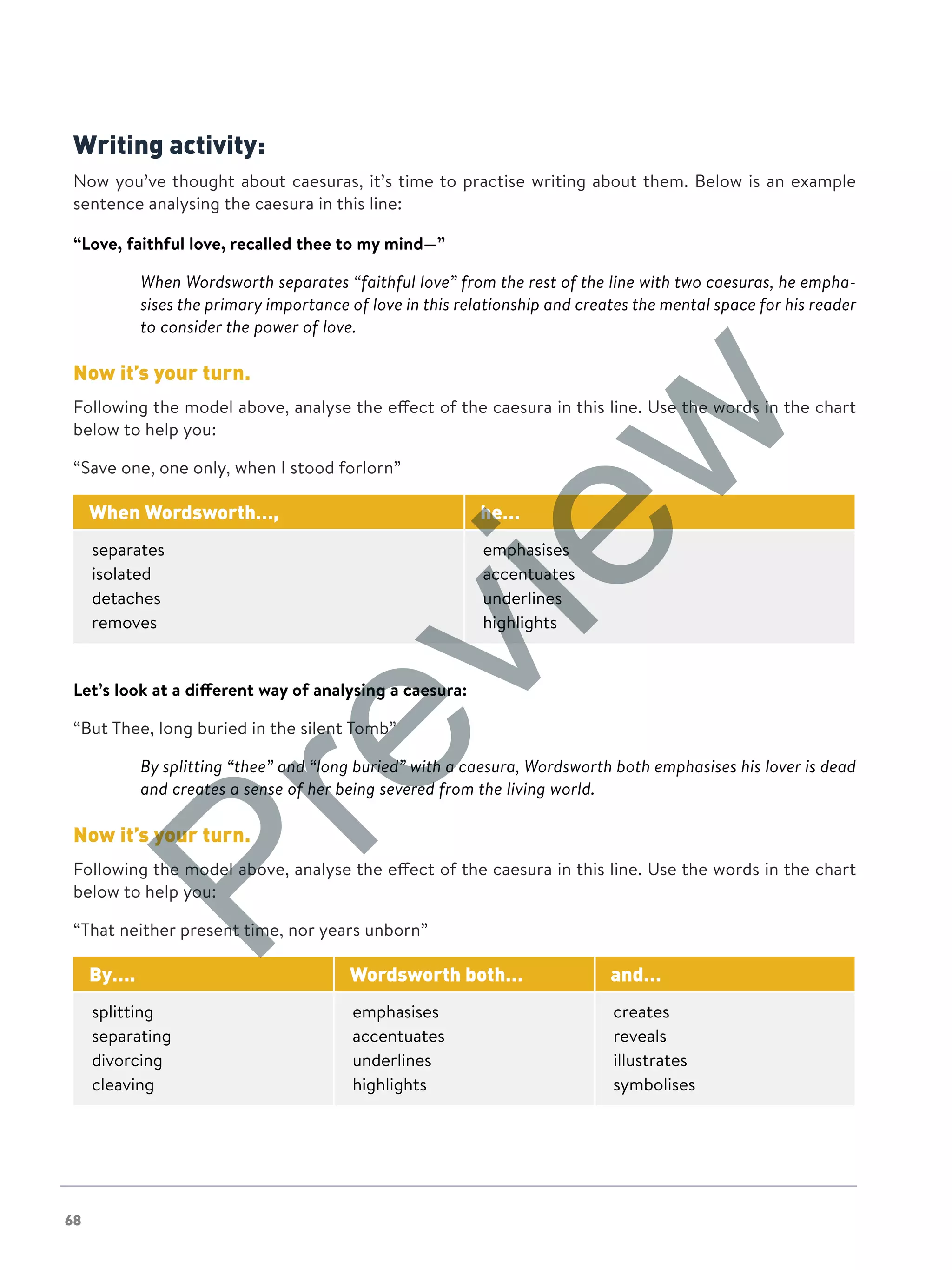

![101SELECTED WORDSWORTH POEMS

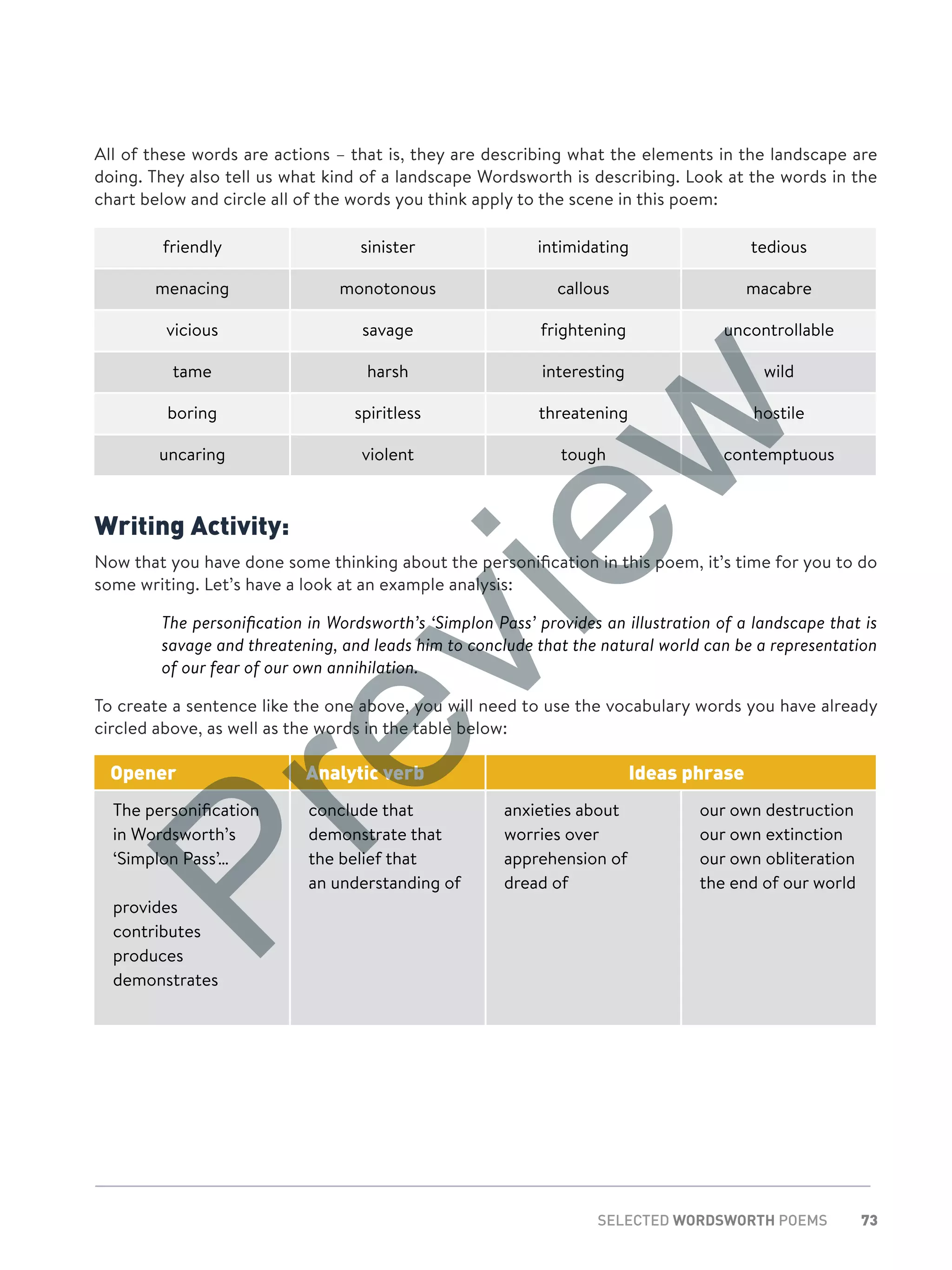

Stanzas 4–6

The big idea

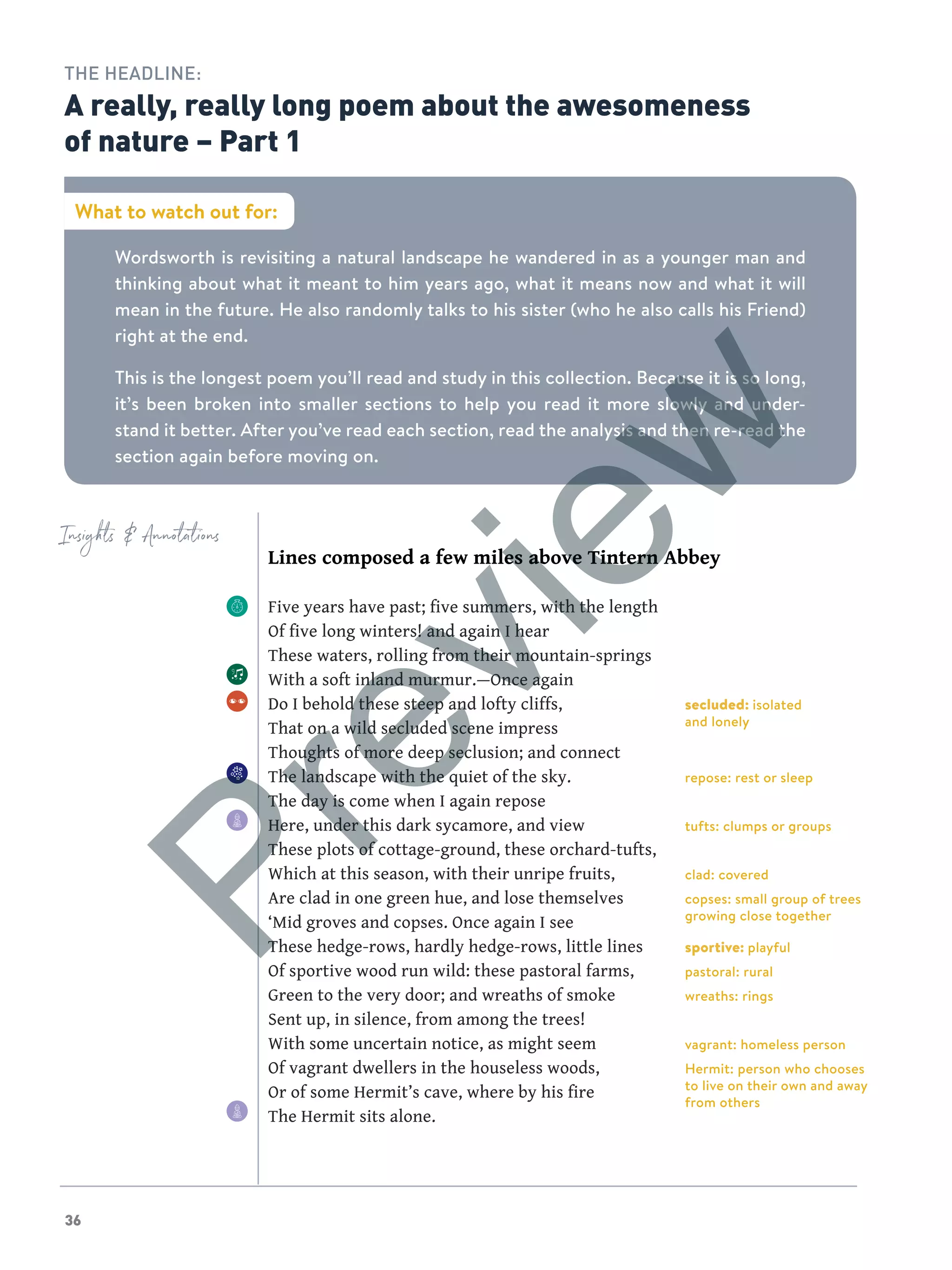

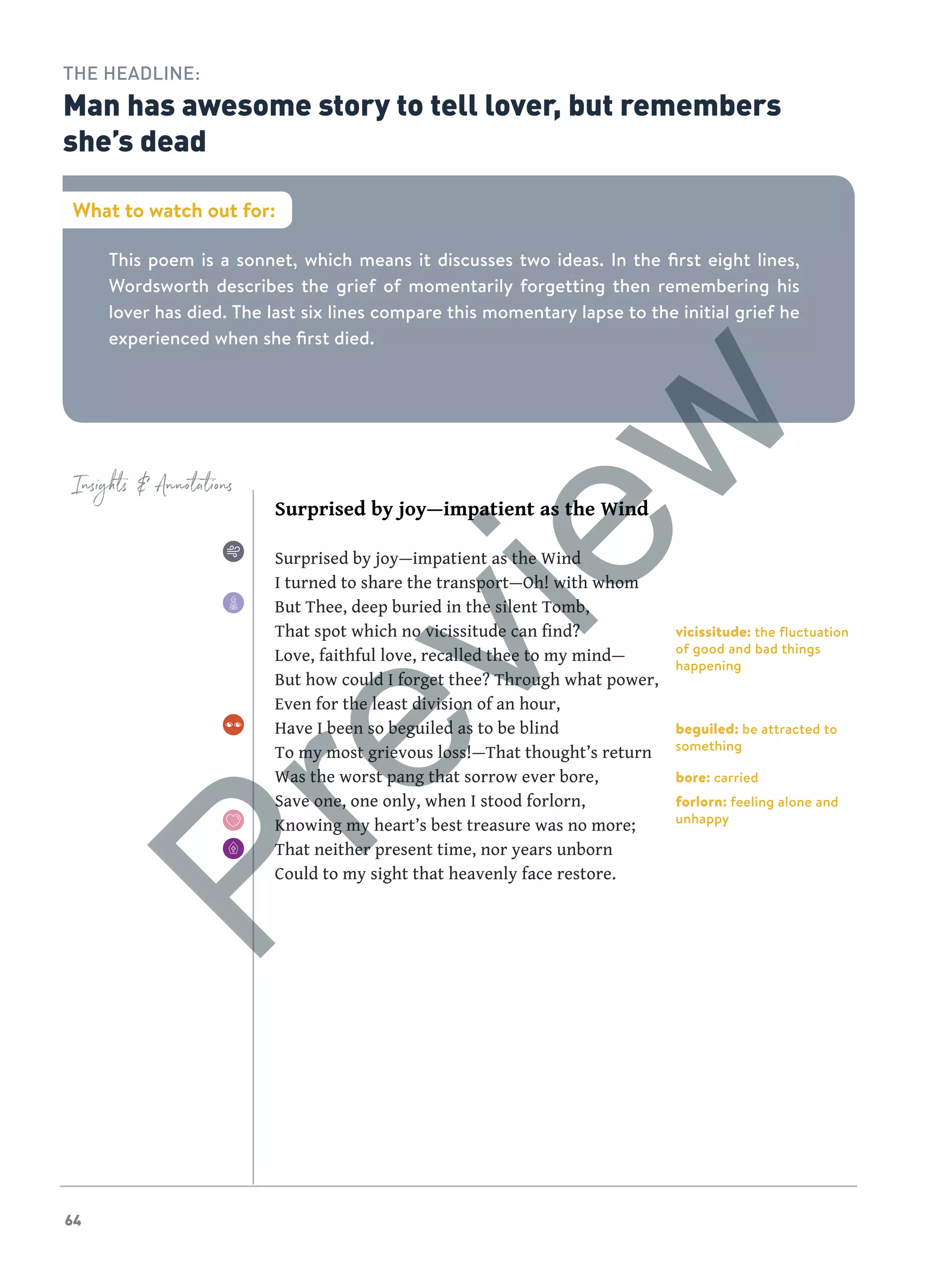

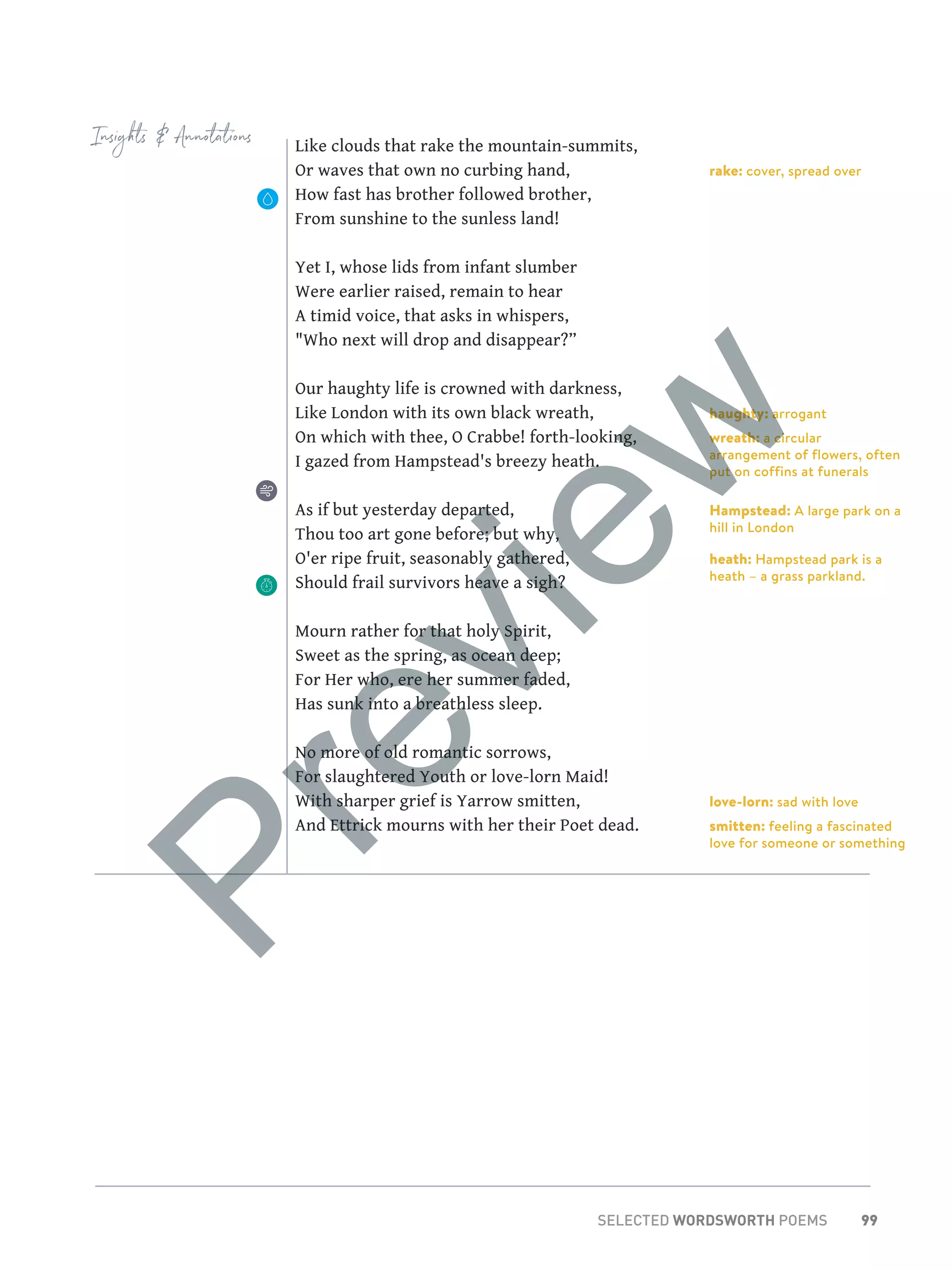

The power of nature and death is unstoppable and has claimed other poets, like Coleridge and

Lamb who have also died recently.

Poem analysis:

Ideas Techniques

It has been two years (“year twice measured”)

since Coleridge has died and, as with Hogg,

Wordsworth describes how the death of

a romantic poet has left life stagnating. In

the case of Coleridge, his work has become

“frozen” by death and by extension, his work is

now stuck in the past. Coleridge is also praised

as being “godlike” and “heaven-eyed”. It is

almost as if Wordsworth imagines Coleridge

as a deity, so influential has his poetry been.

Next, Wordsworth pays homage to Charles

Lamb. Here, because of both his name and

poetry, Lamb is a symbol of innocence,

whose poetry “frolic[s]”. The sixth stanza

emphasises the inevitability of death. Already,

Wordsworth has described time and nature

as “stedfast” (i.e. unstoppable), and in this

stanza he sees the force of nature and death

as like waves which are controlled by “no

curbing hand” or like clouds which “rake” or

can completely cover the highest mountains

(poets being the mountains in this metaphor).

Wordsworth inverts his usual use of water

imagery to symbolise the romantic ideals

of the free-flowing movement of ideas and

feelings in nature to describe Coleridge as like

a river that has been “frozen”. However, in the

sixth stanza, he returns to his more usual use

of water and air imagery. In this stanza, nature

and death are symbolised as unstoppable

clouds and waves – two elements above and

beyond the human earth. As such, these

elements are beyond human control and we

must submit to them.

Preview](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectedwordsworthpoems-preview-191209213923/75/Selected-Wordsworth-Poems-How-to-read-them-understand-them-and-write-truly-insightful-analyses-on-them-101-2048.jpg)