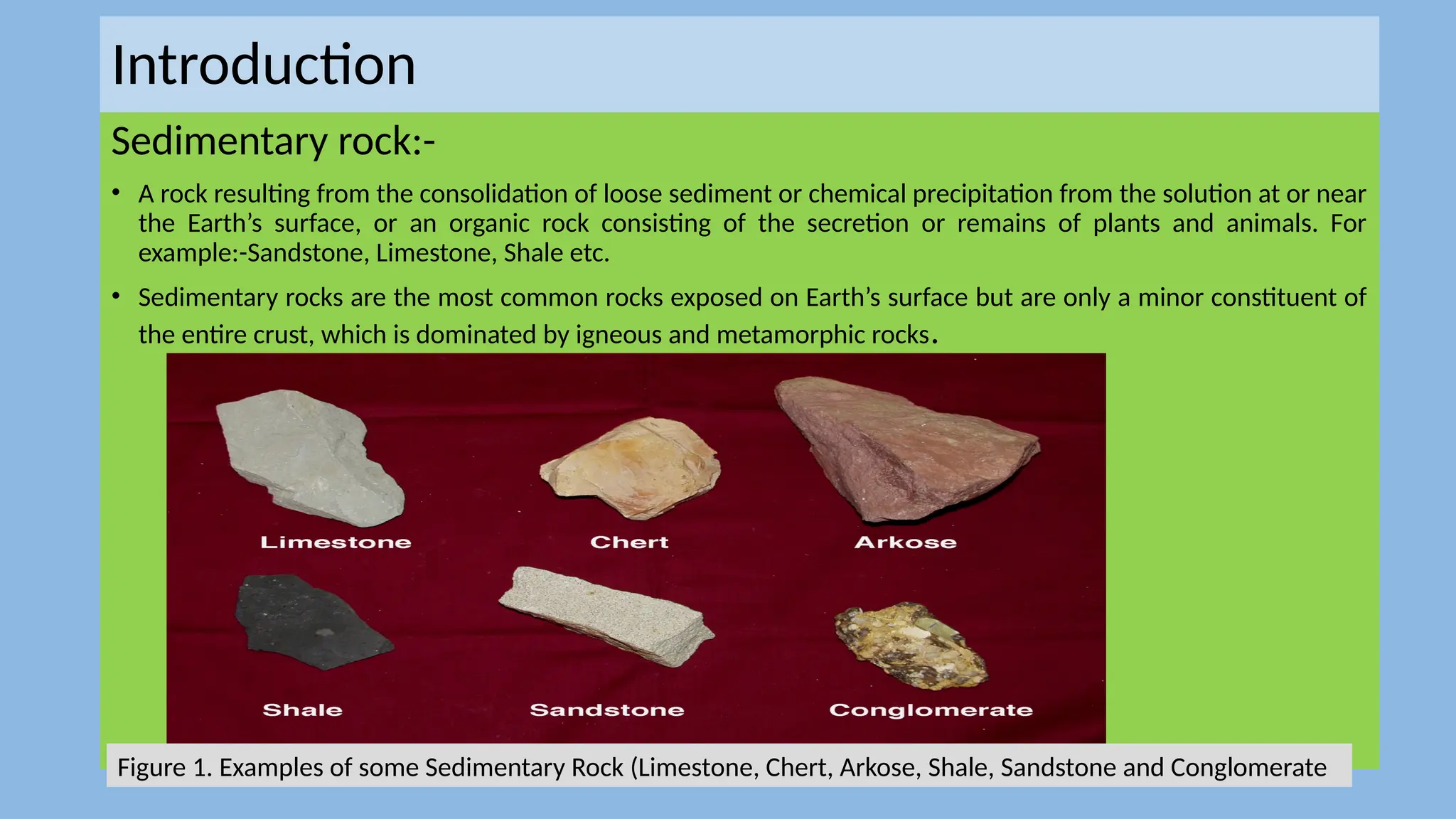

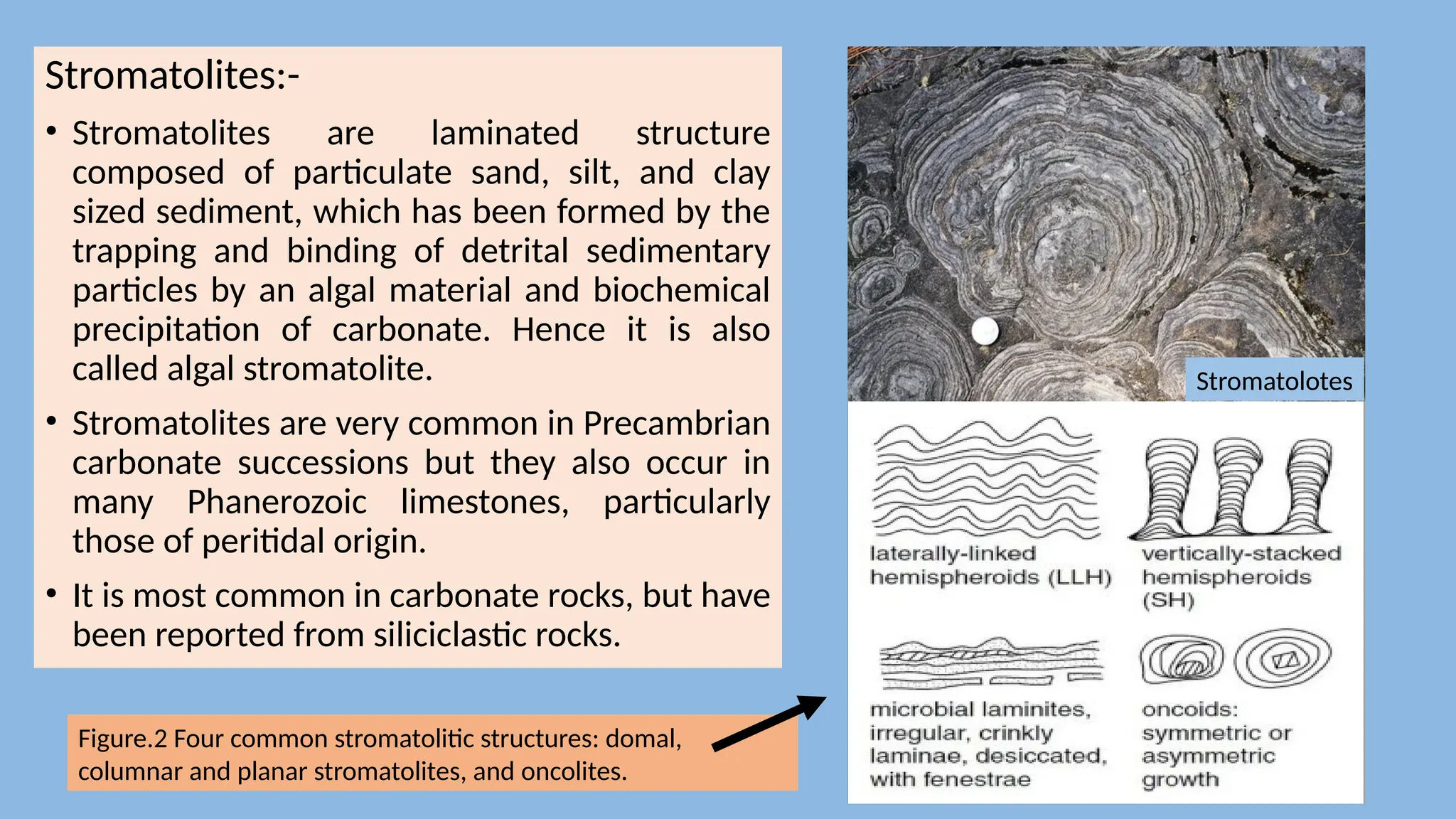

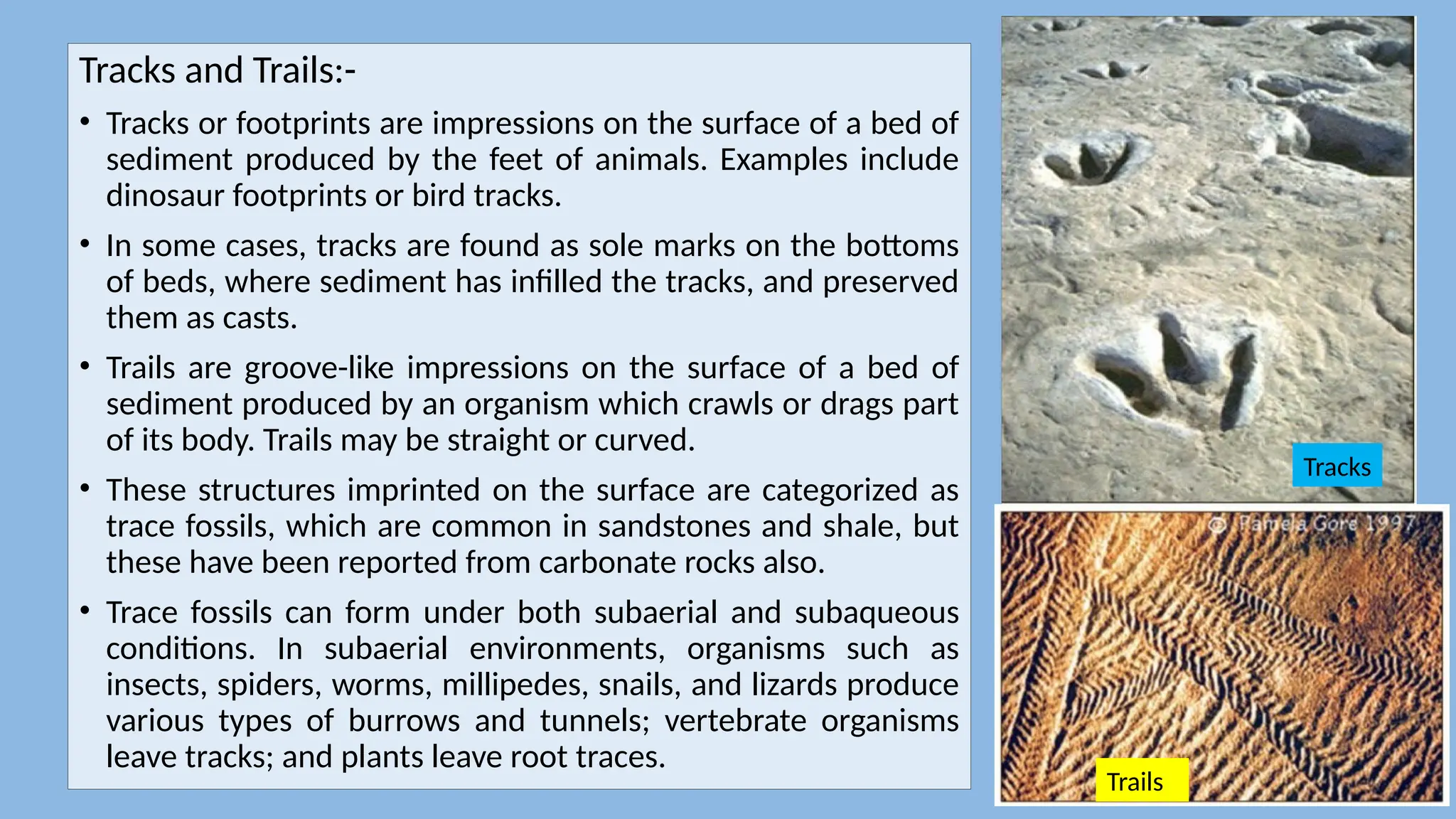

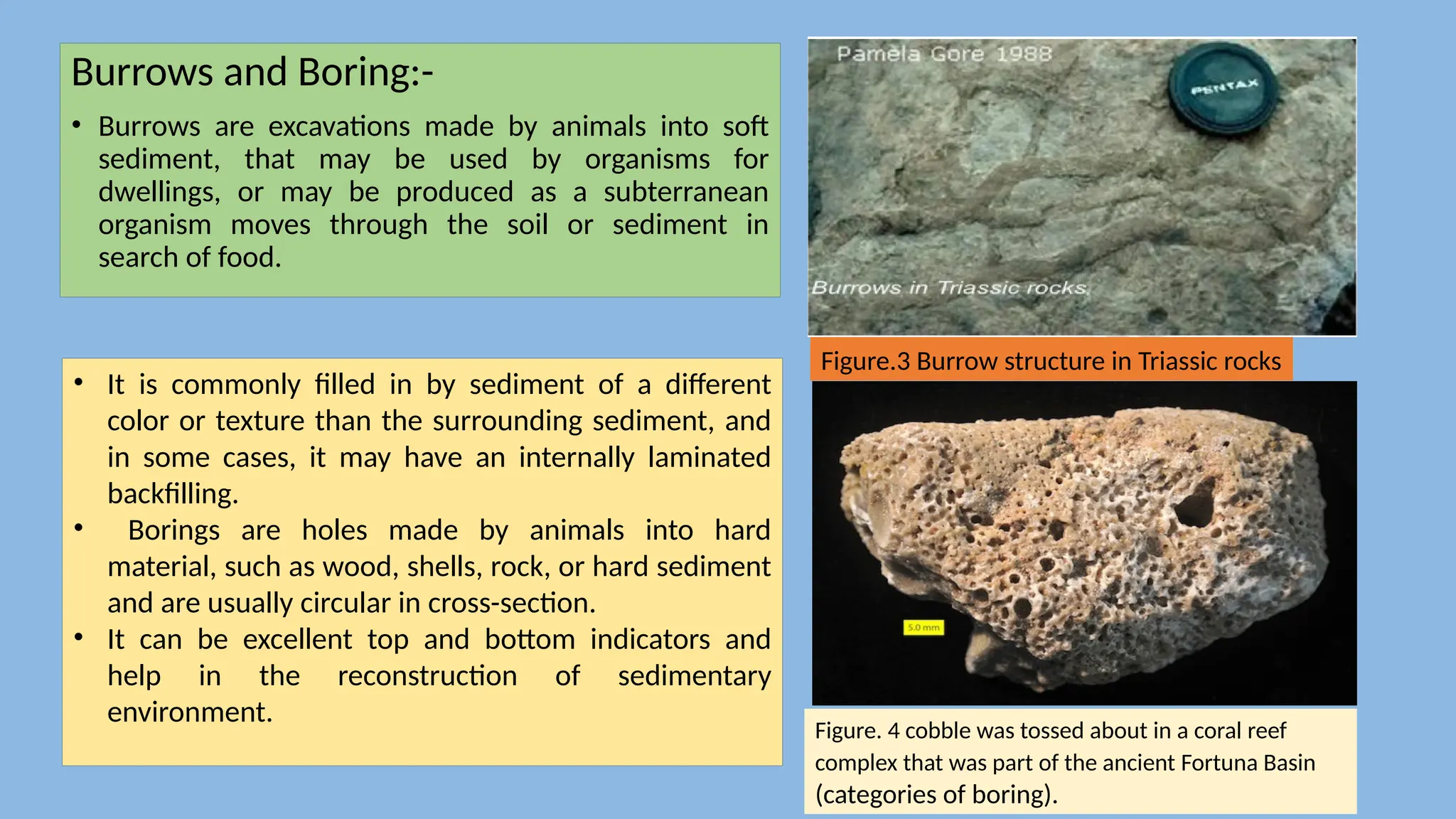

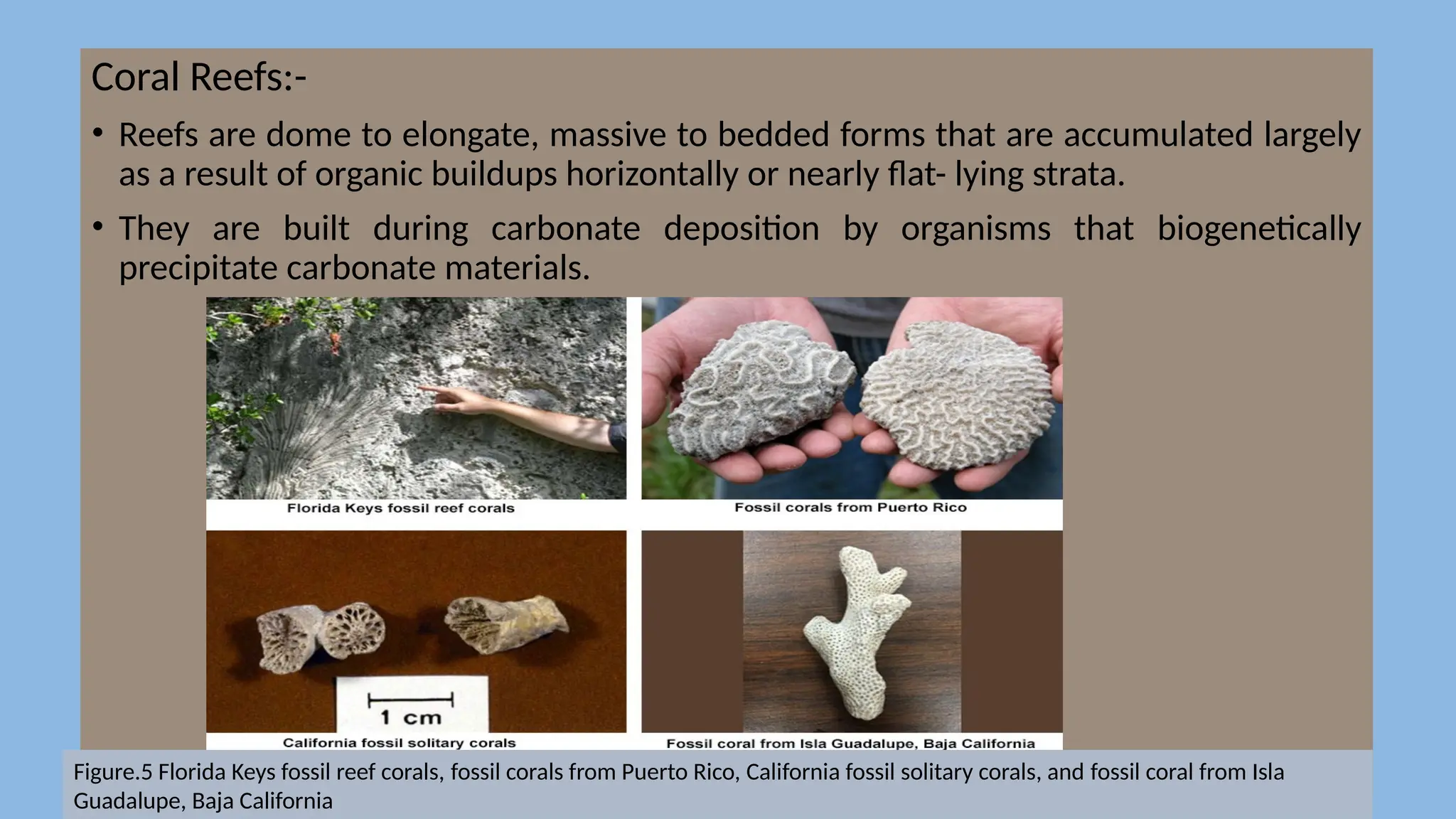

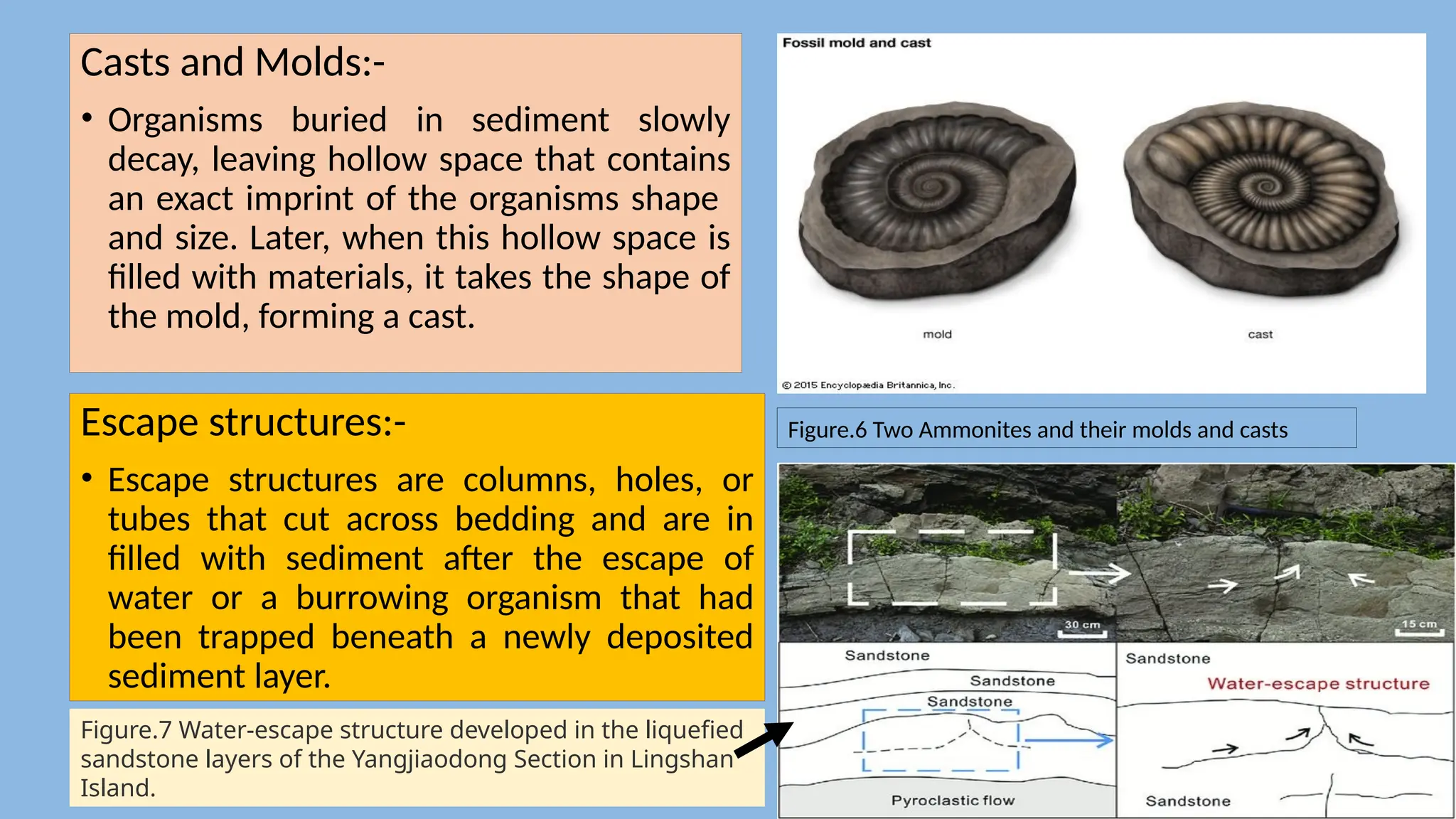

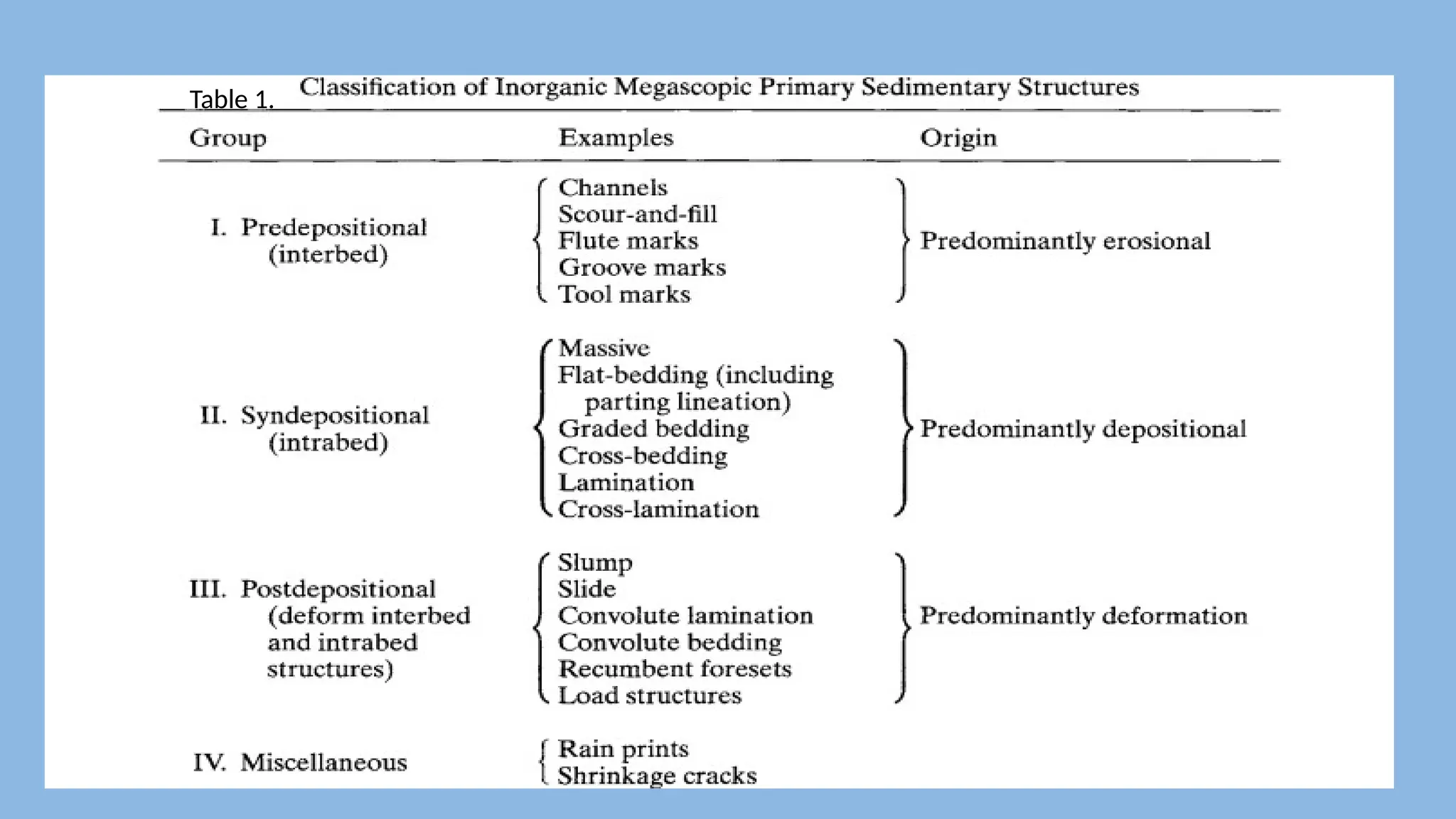

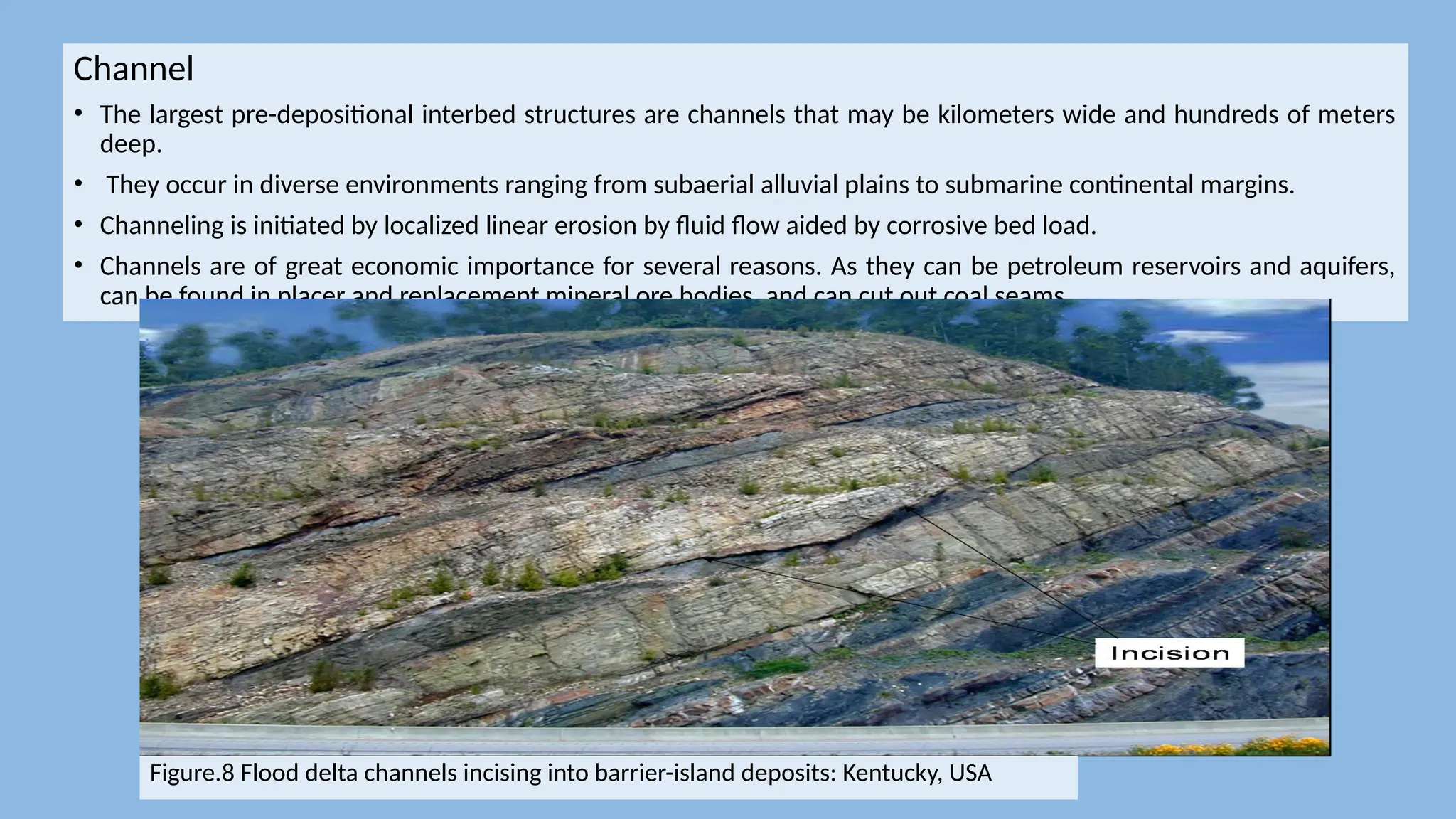

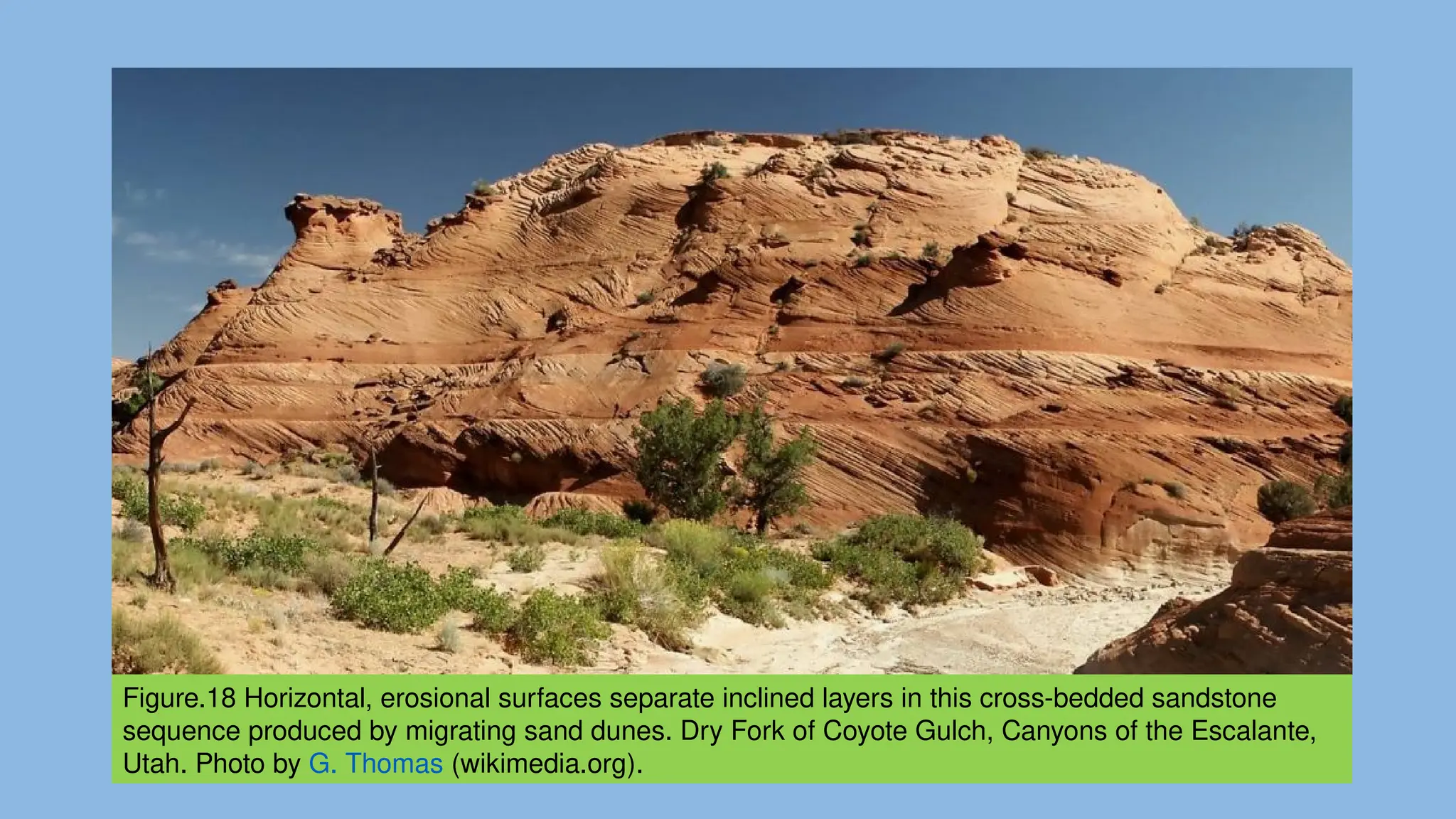

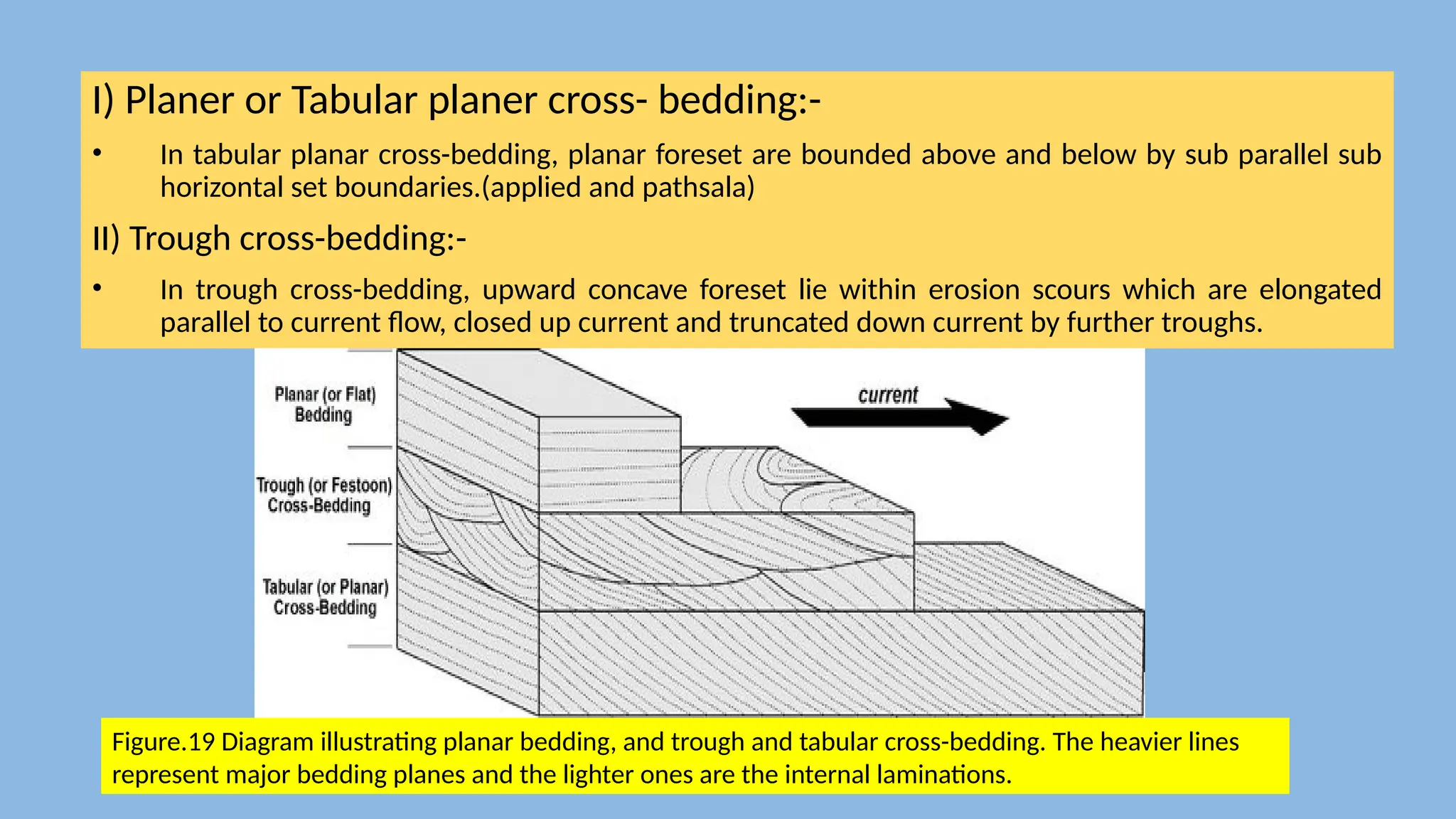

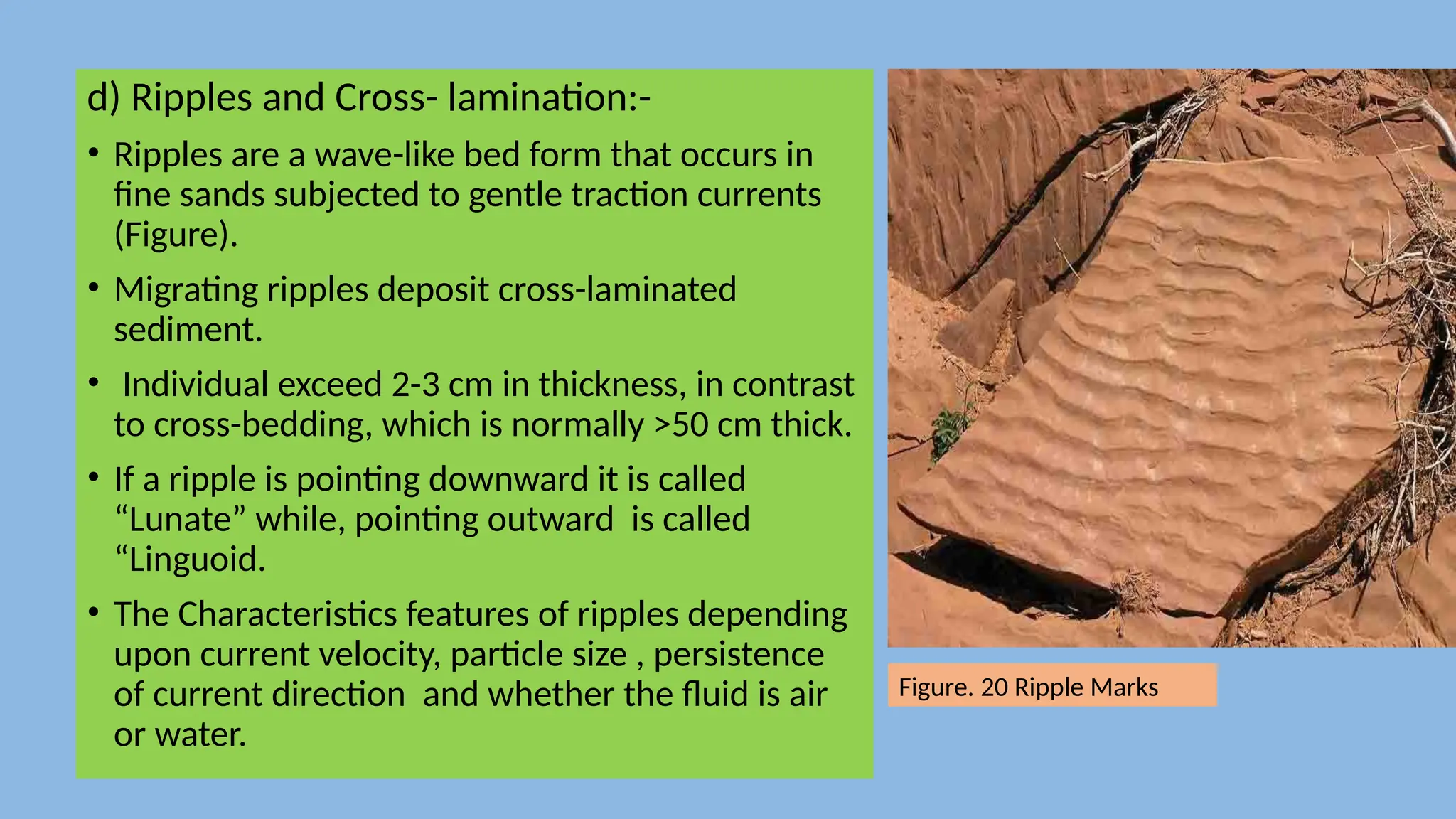

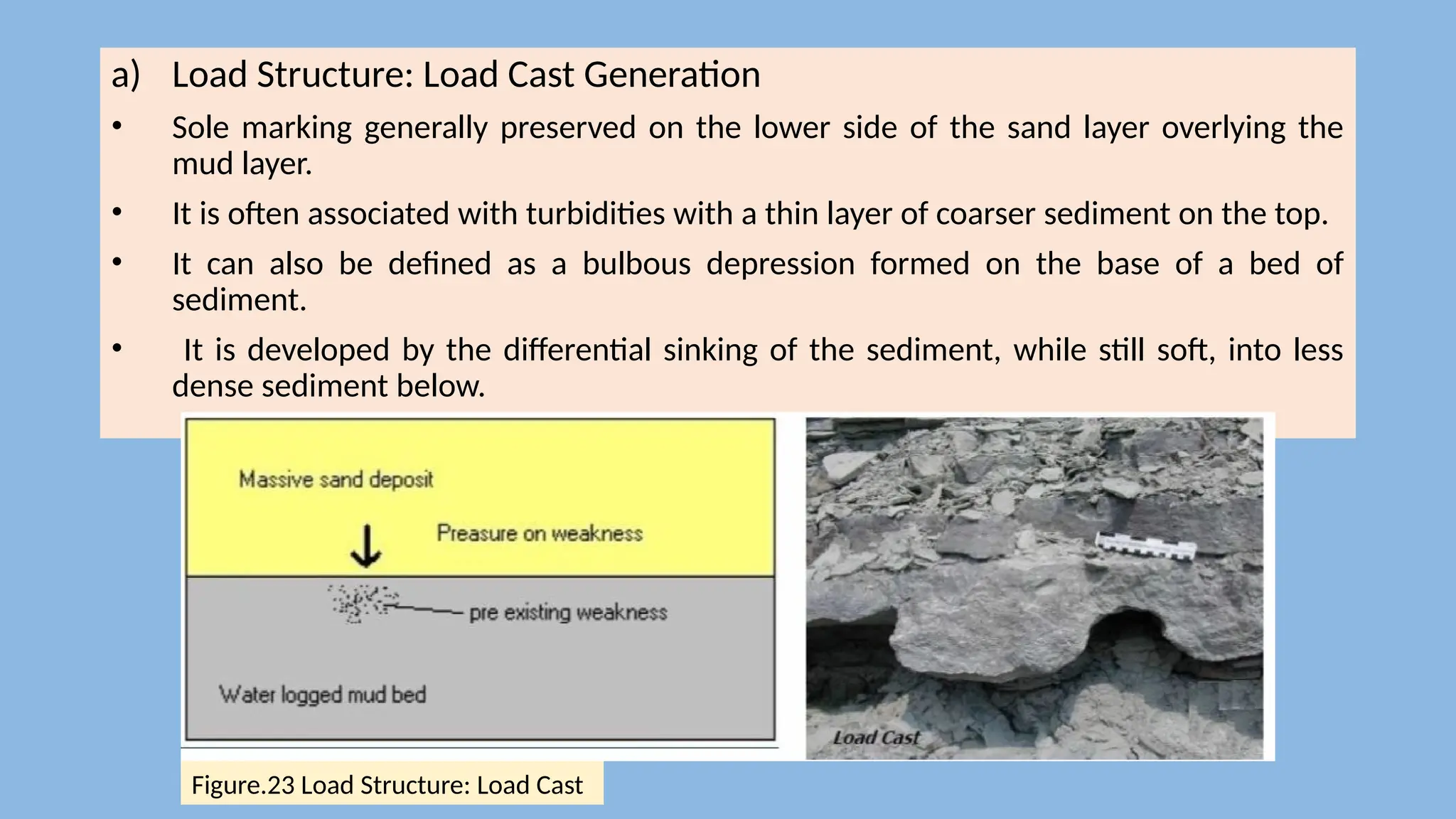

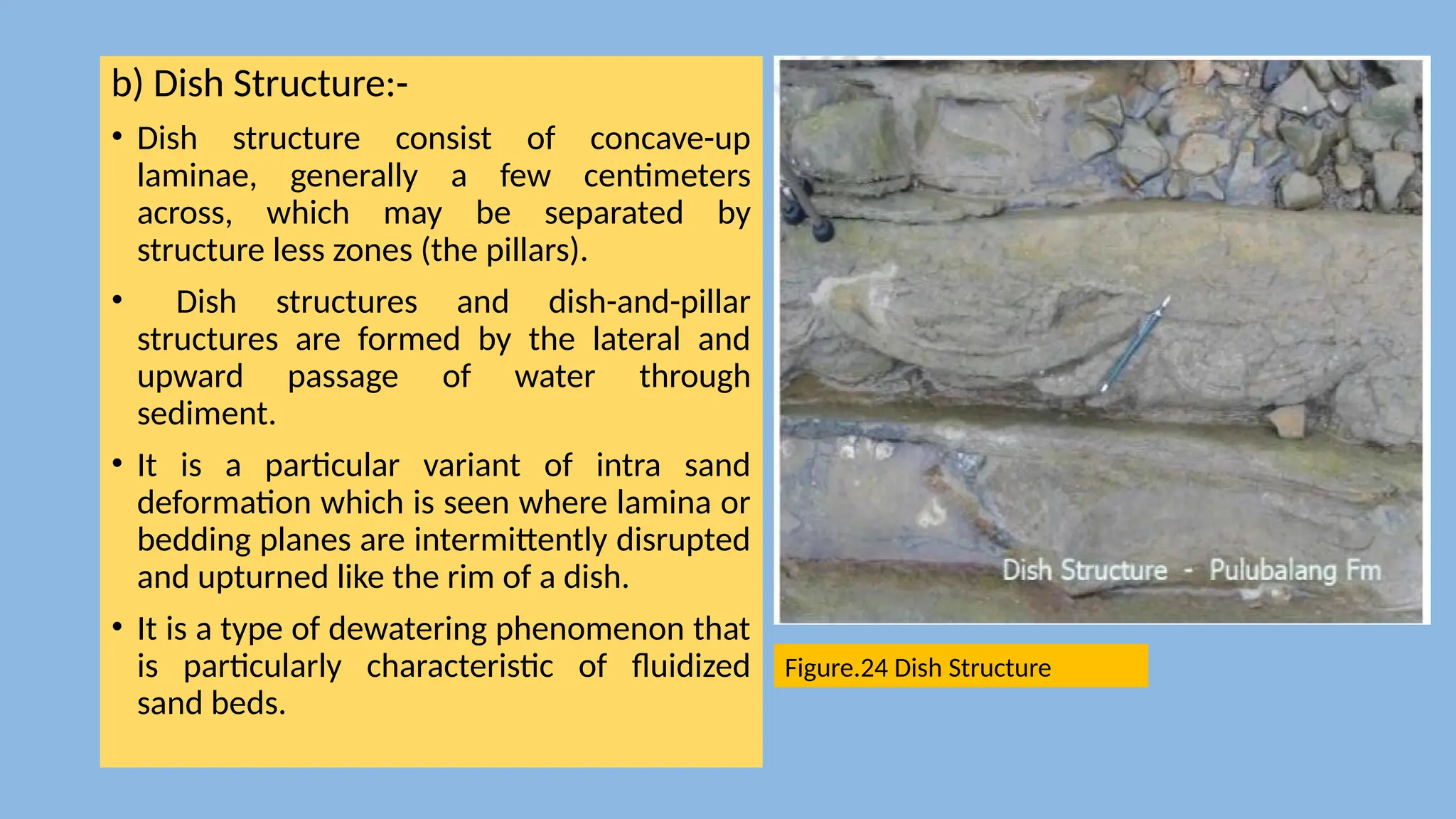

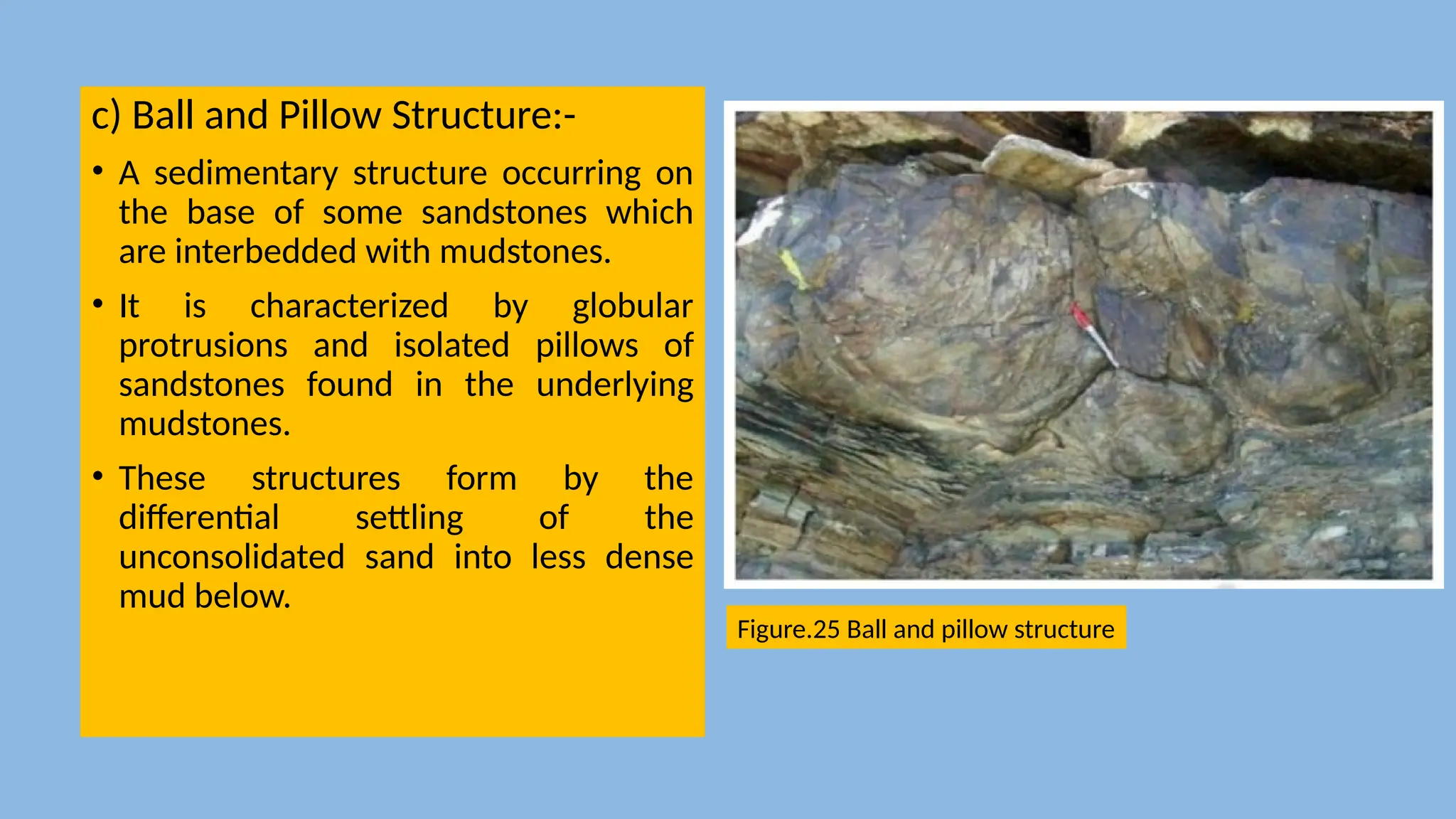

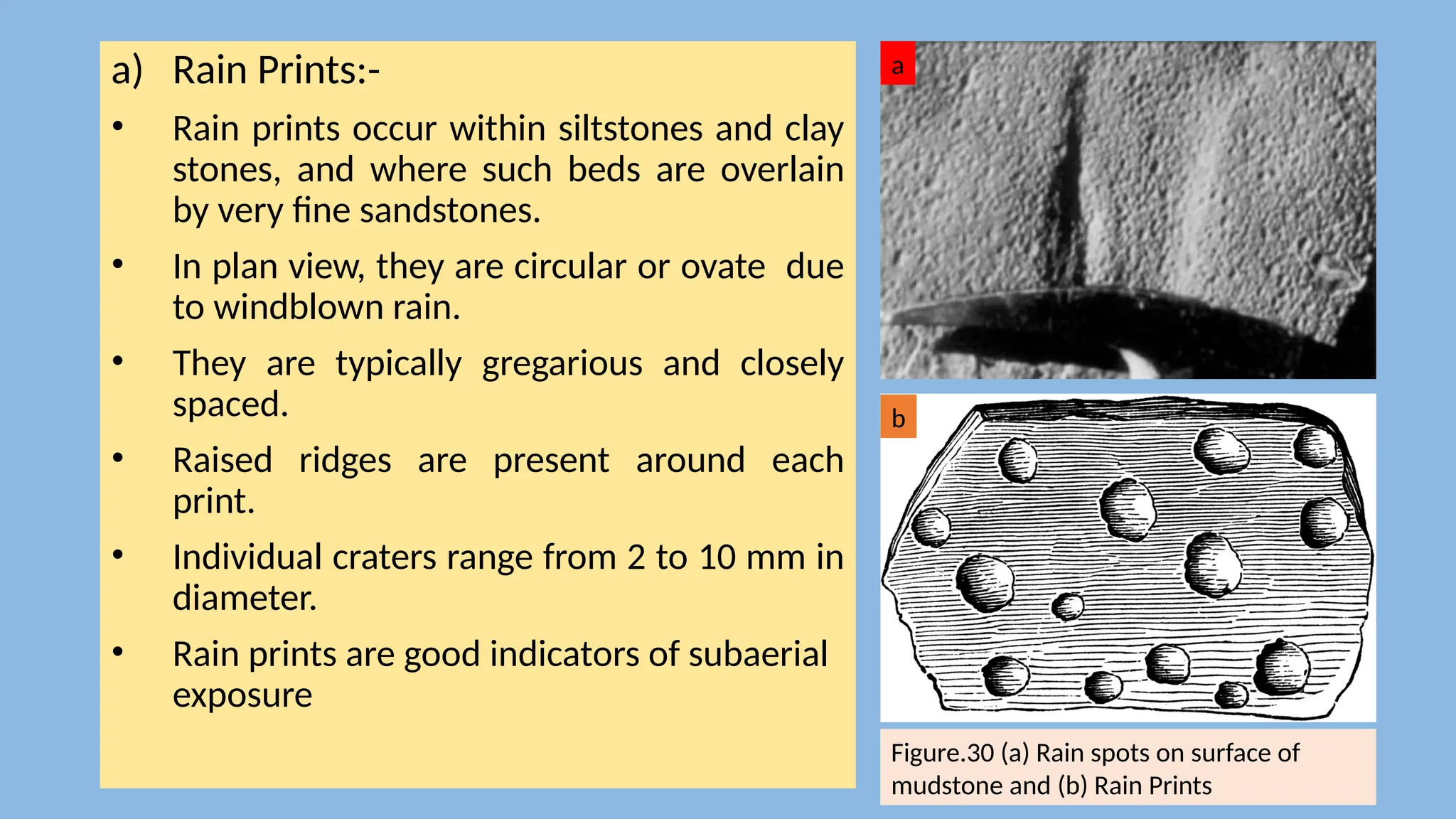

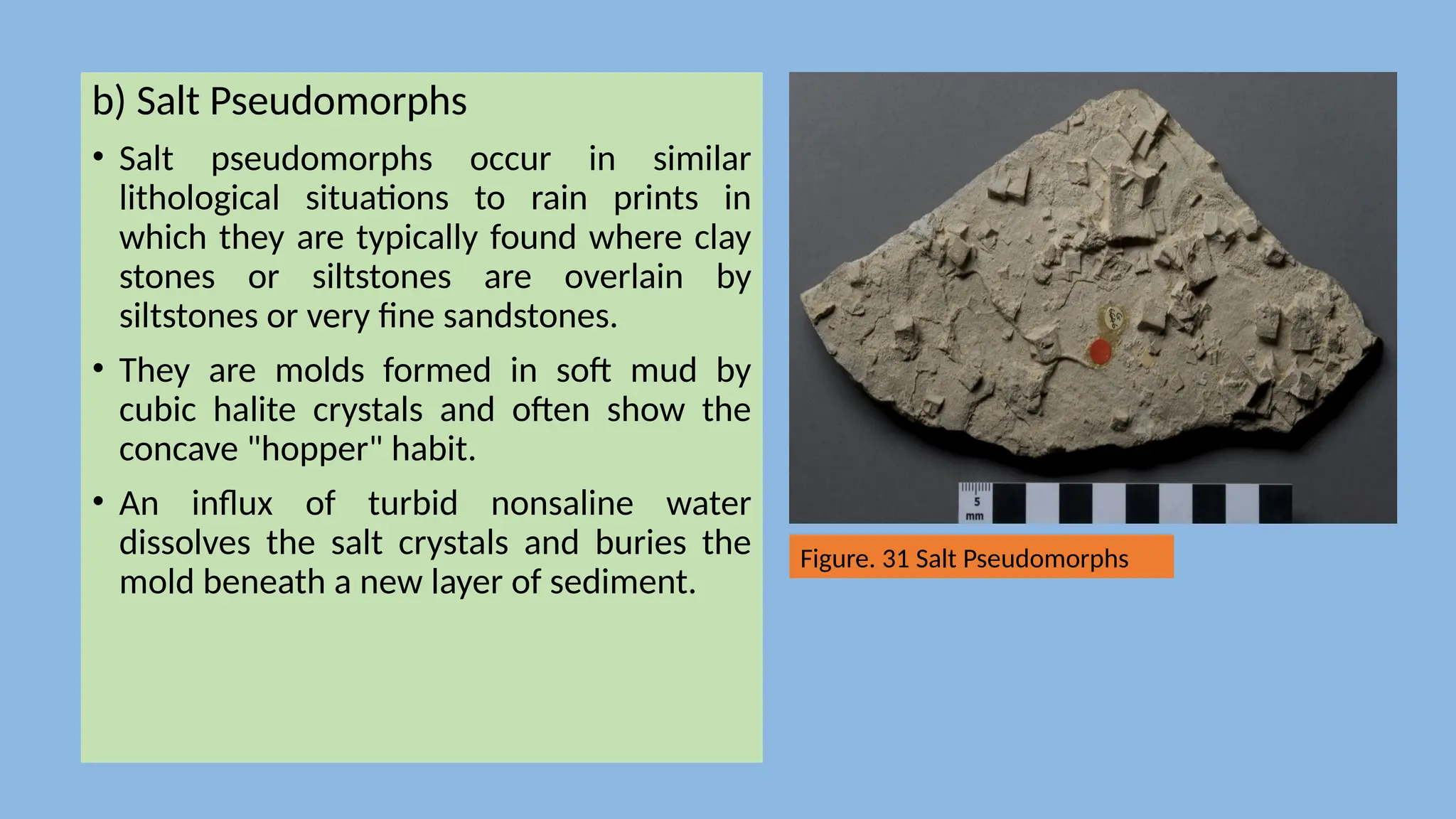

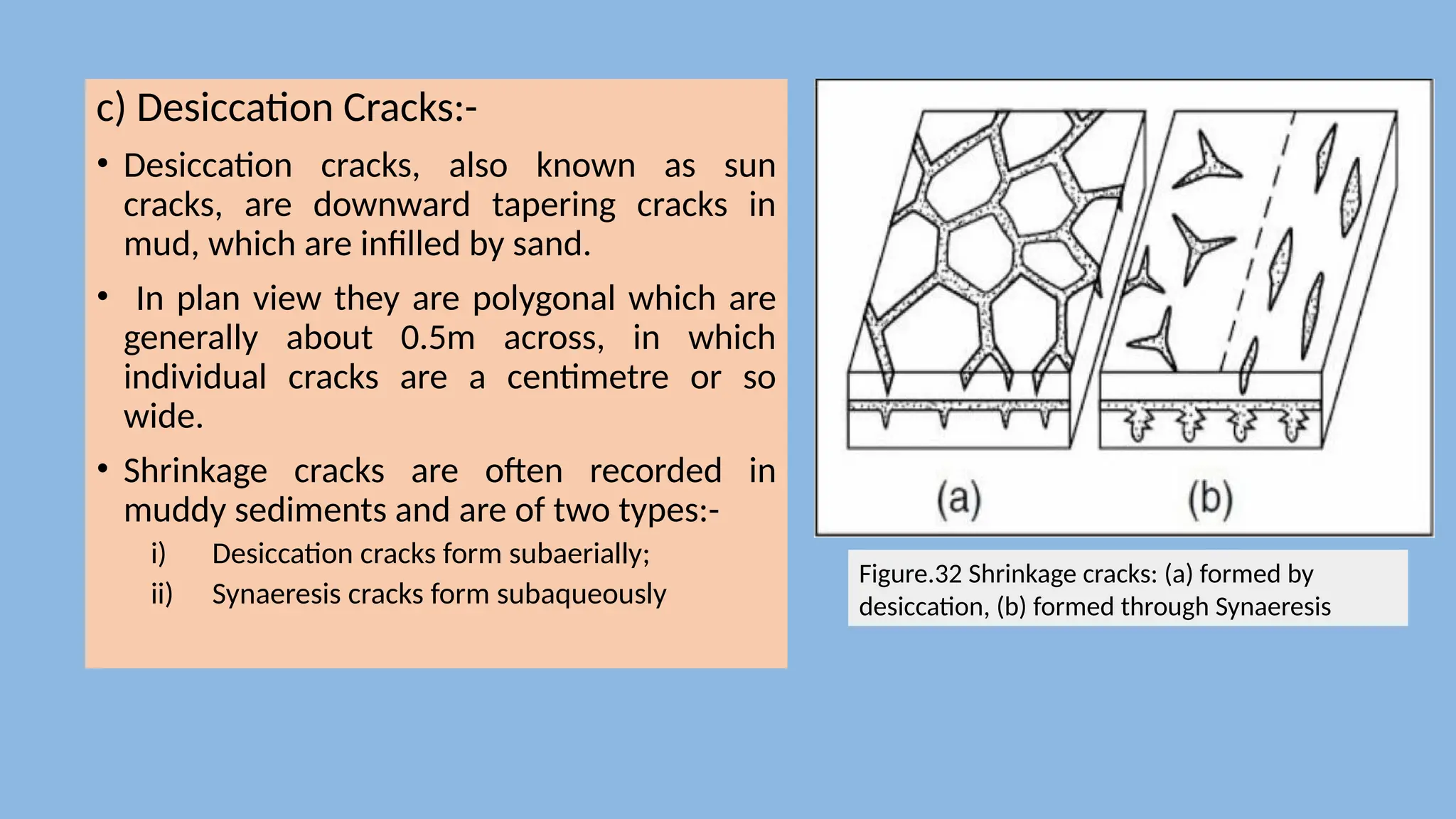

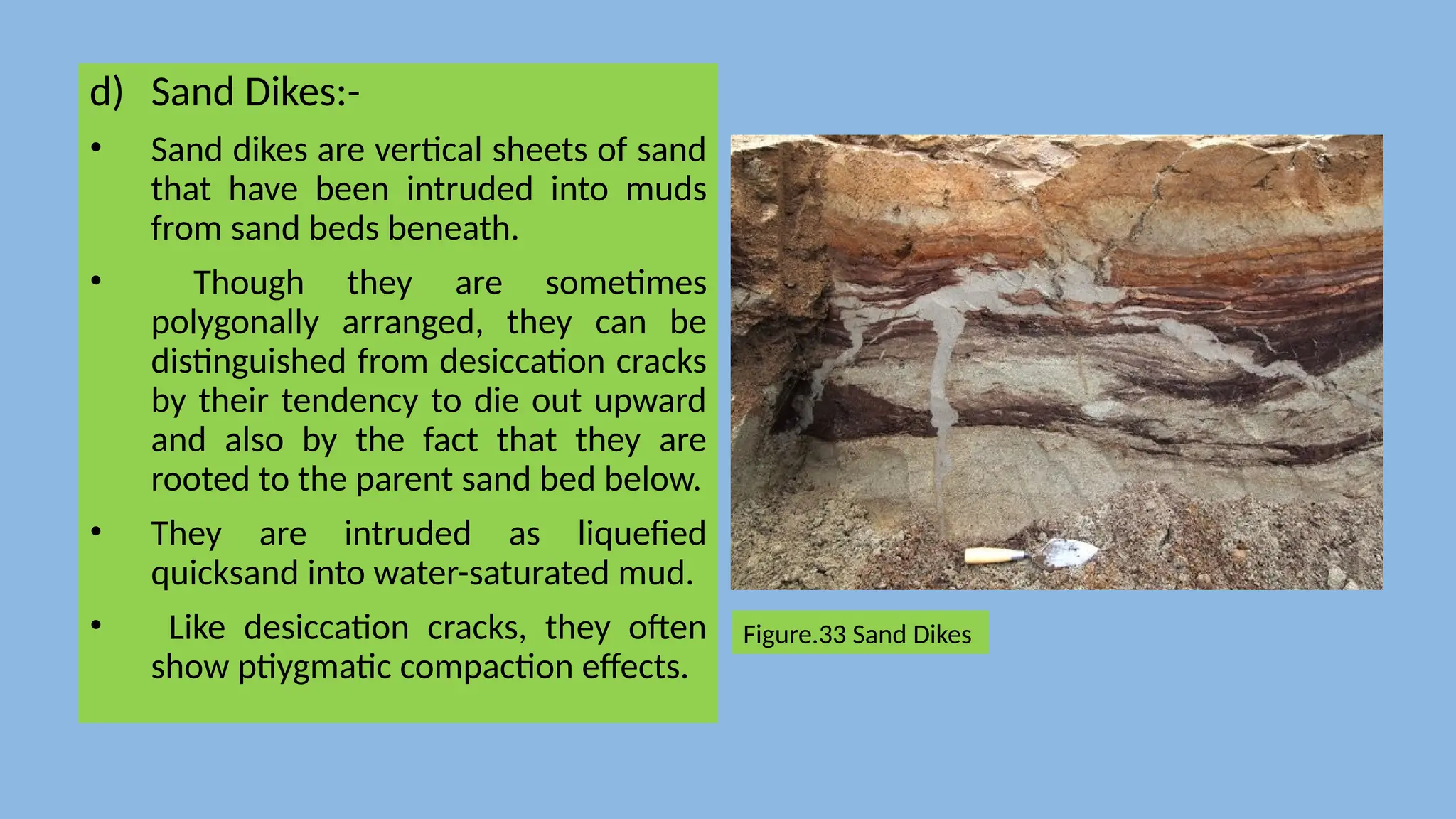

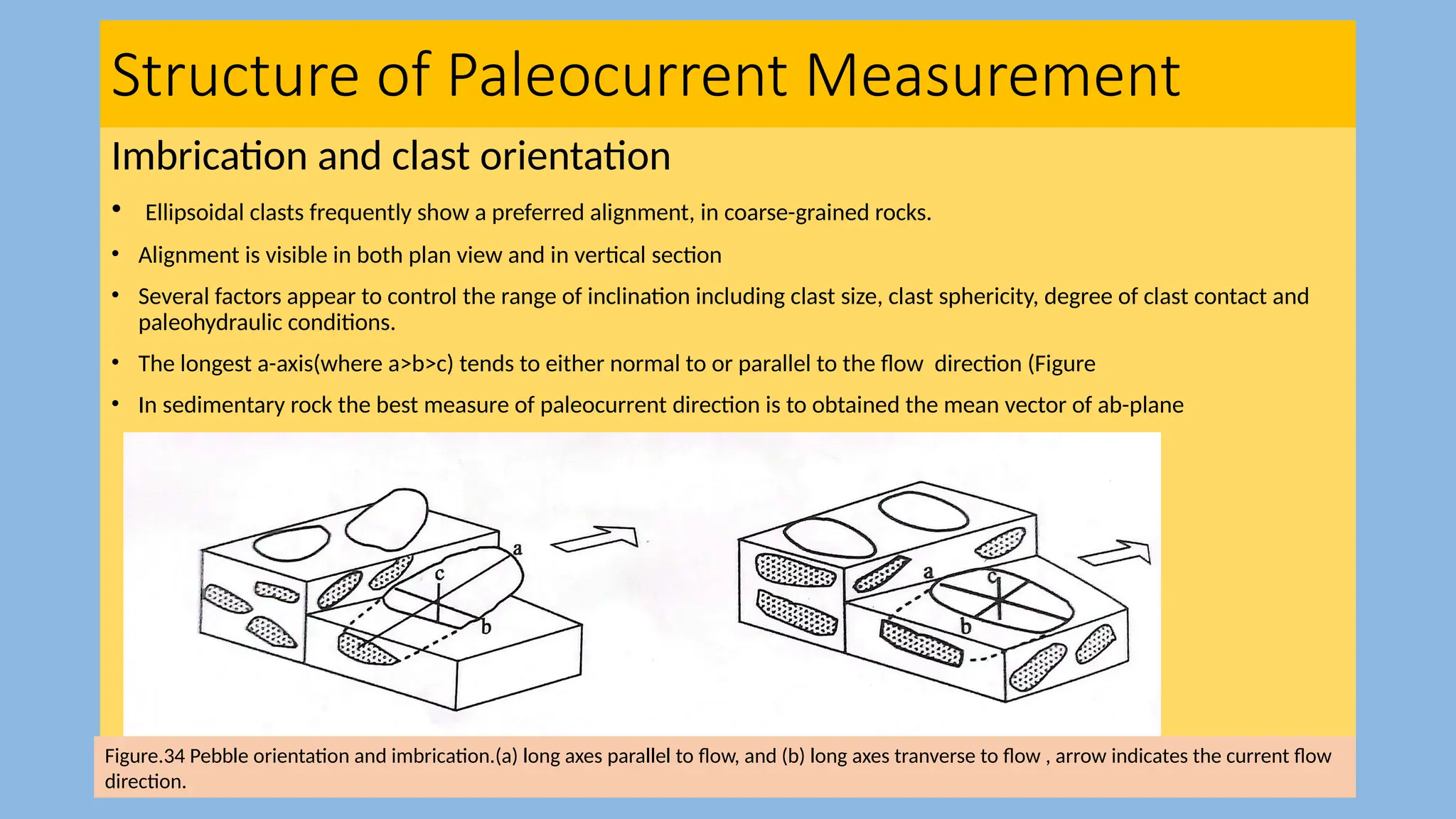

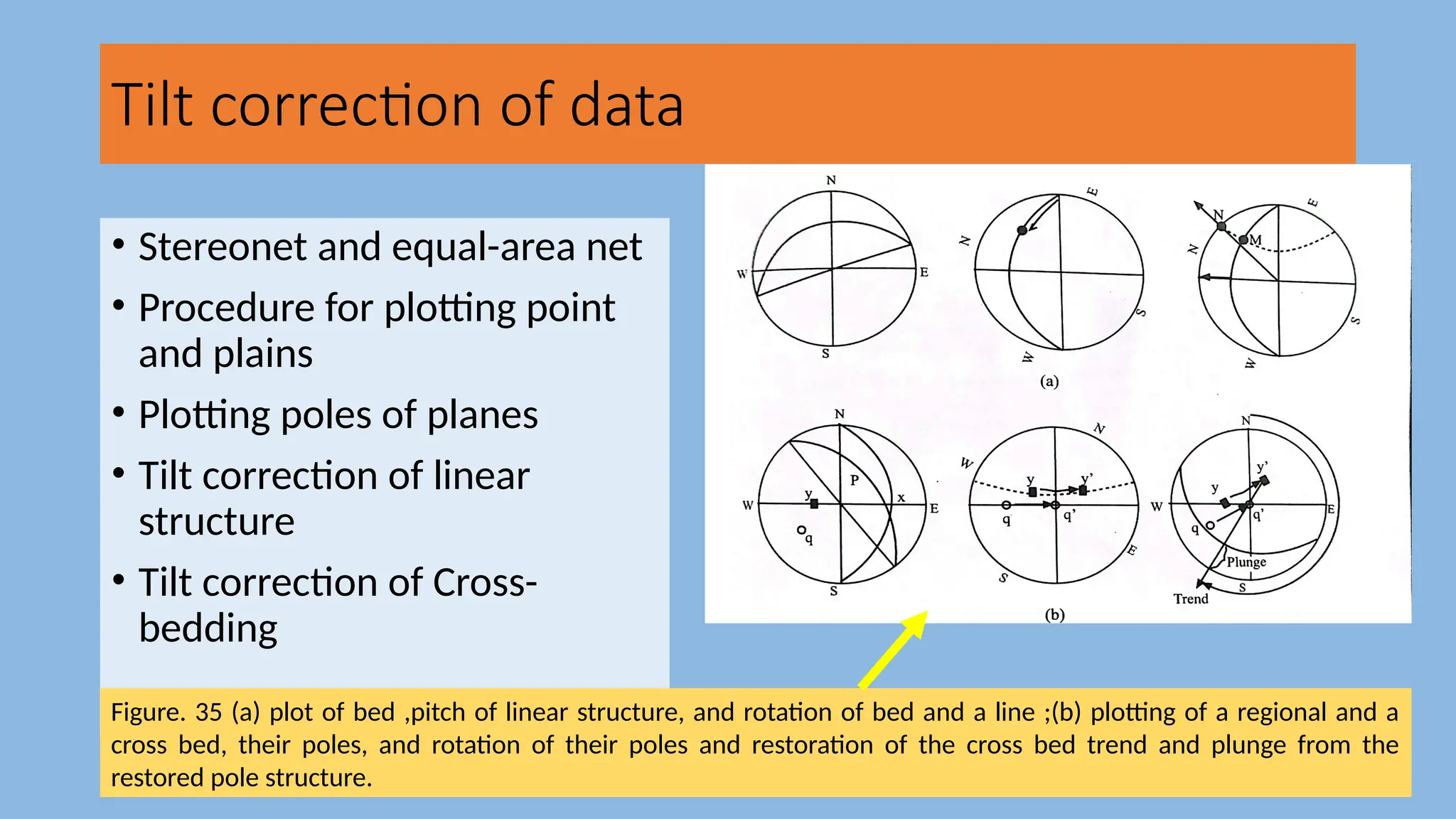

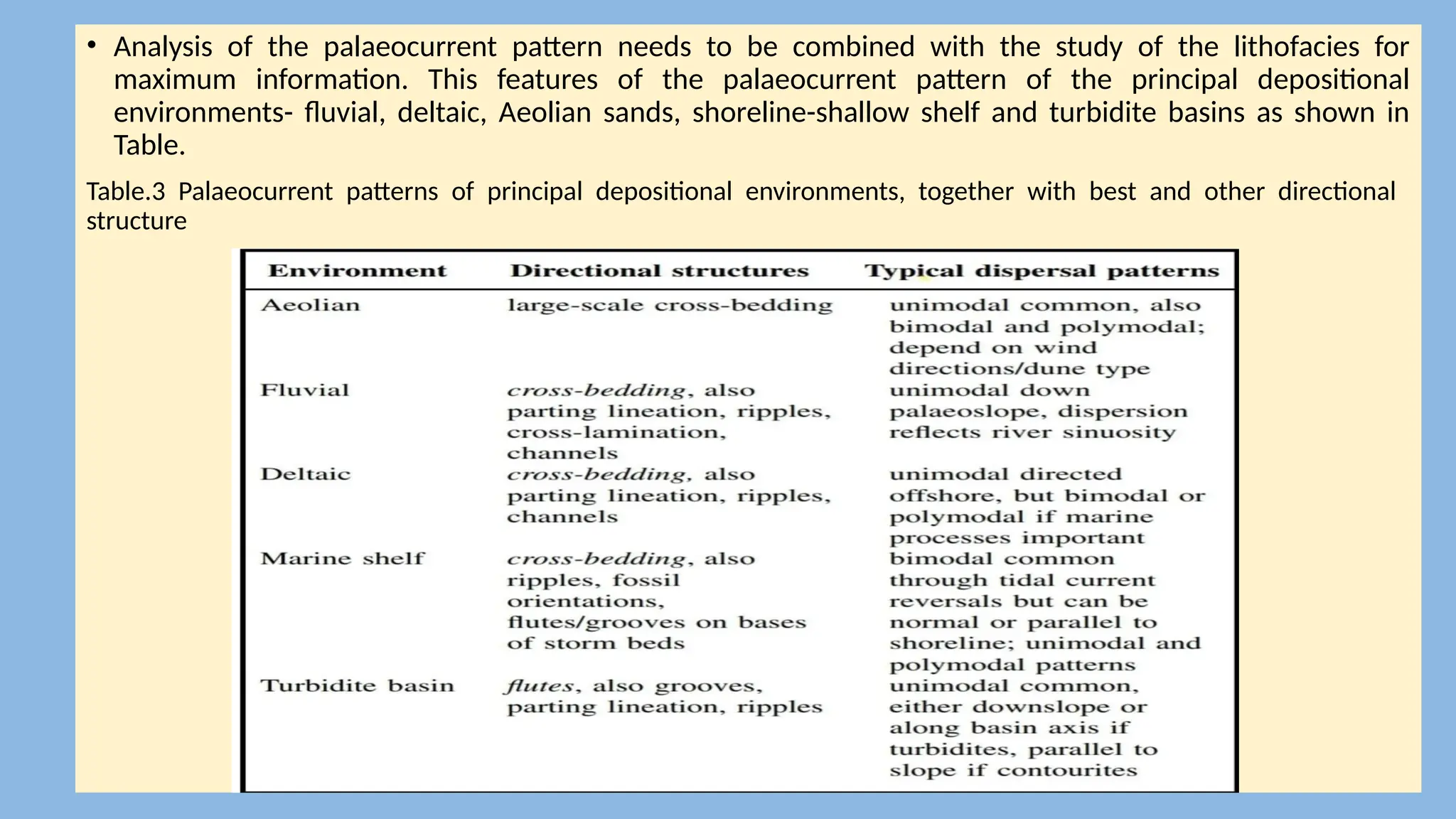

The document presents an in-depth analysis of sedimentary structures and paleocurrent analysis, providing a detailed classification of both biogenic and inorganic sedimentary structures. It discusses the significance of these structures in understanding sedimentary environments, including their formation processes and various types, such as primary, secondary, and post-depositional structures. Key features such as tracks, trails, burrows, and borings are explored, highlighting their role in interpreting paleodepositional conditions.