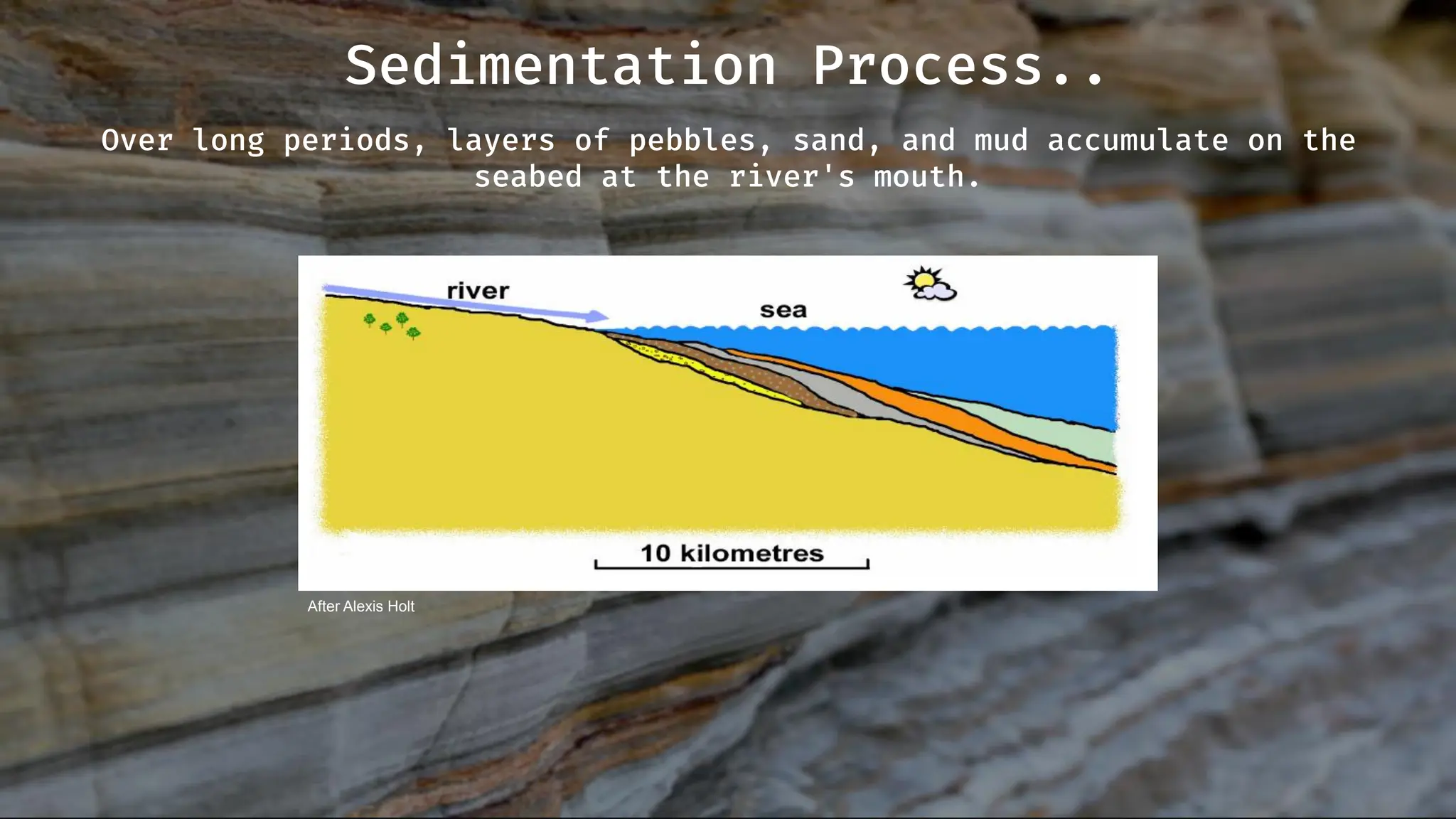

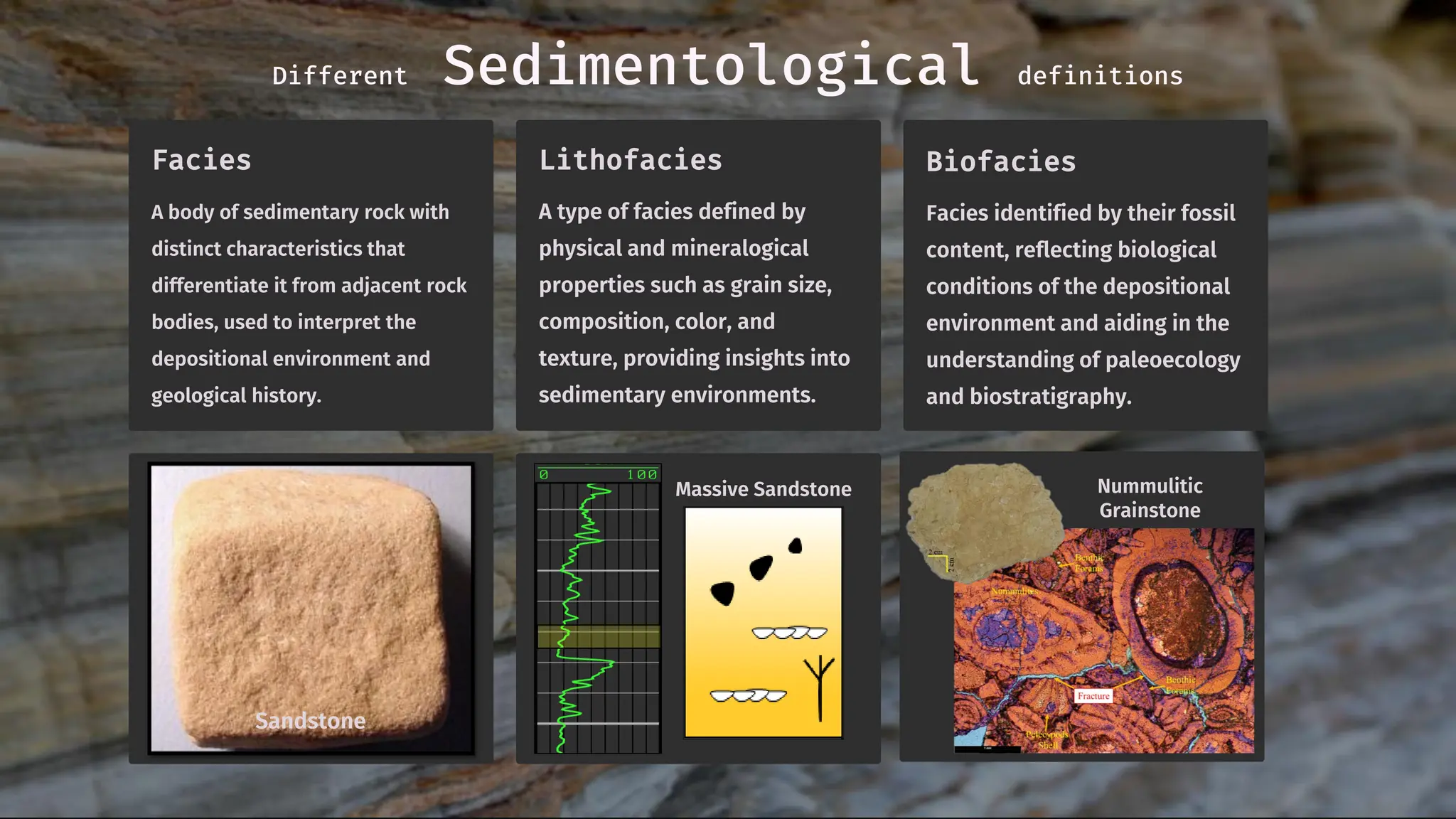

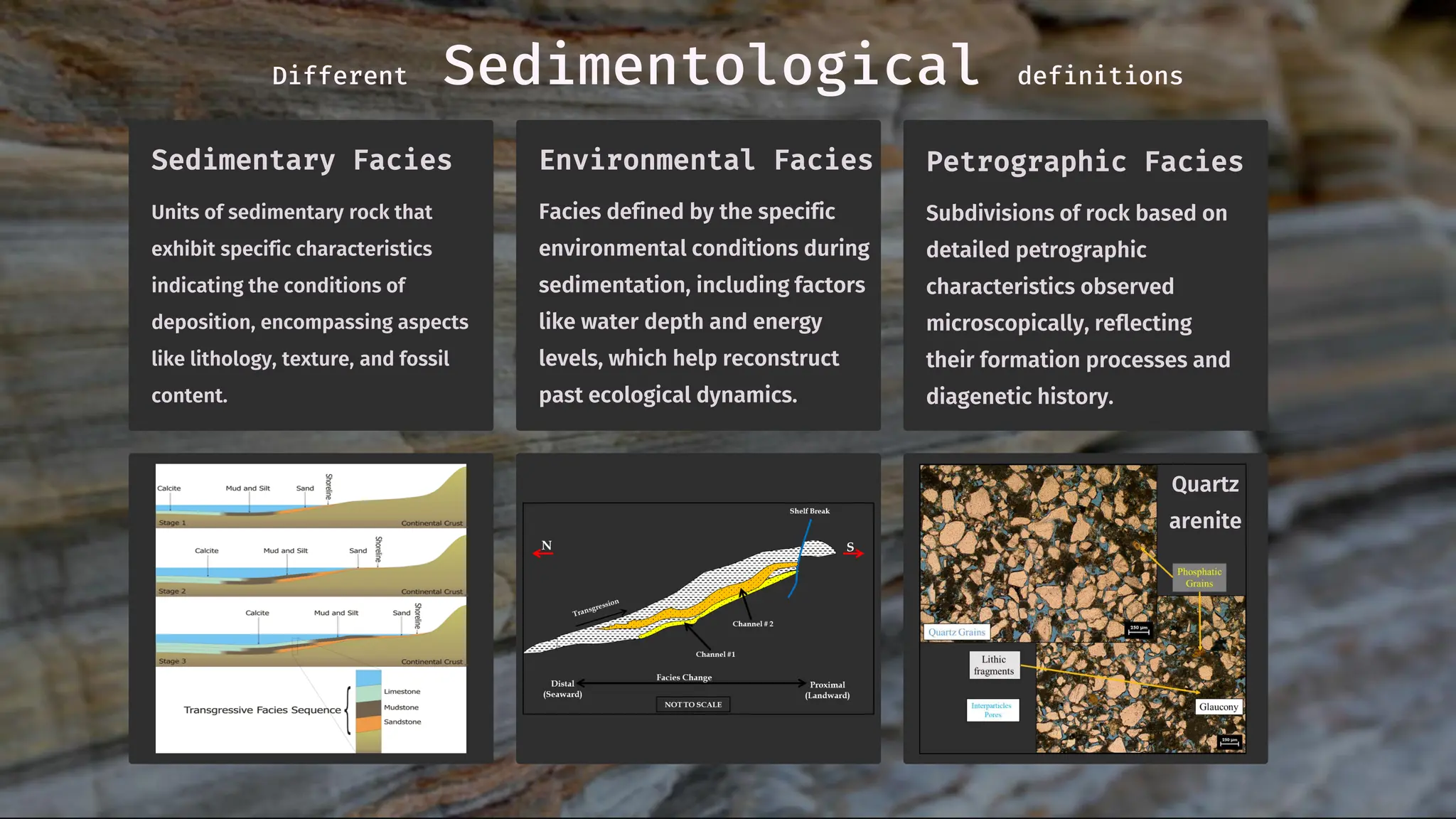

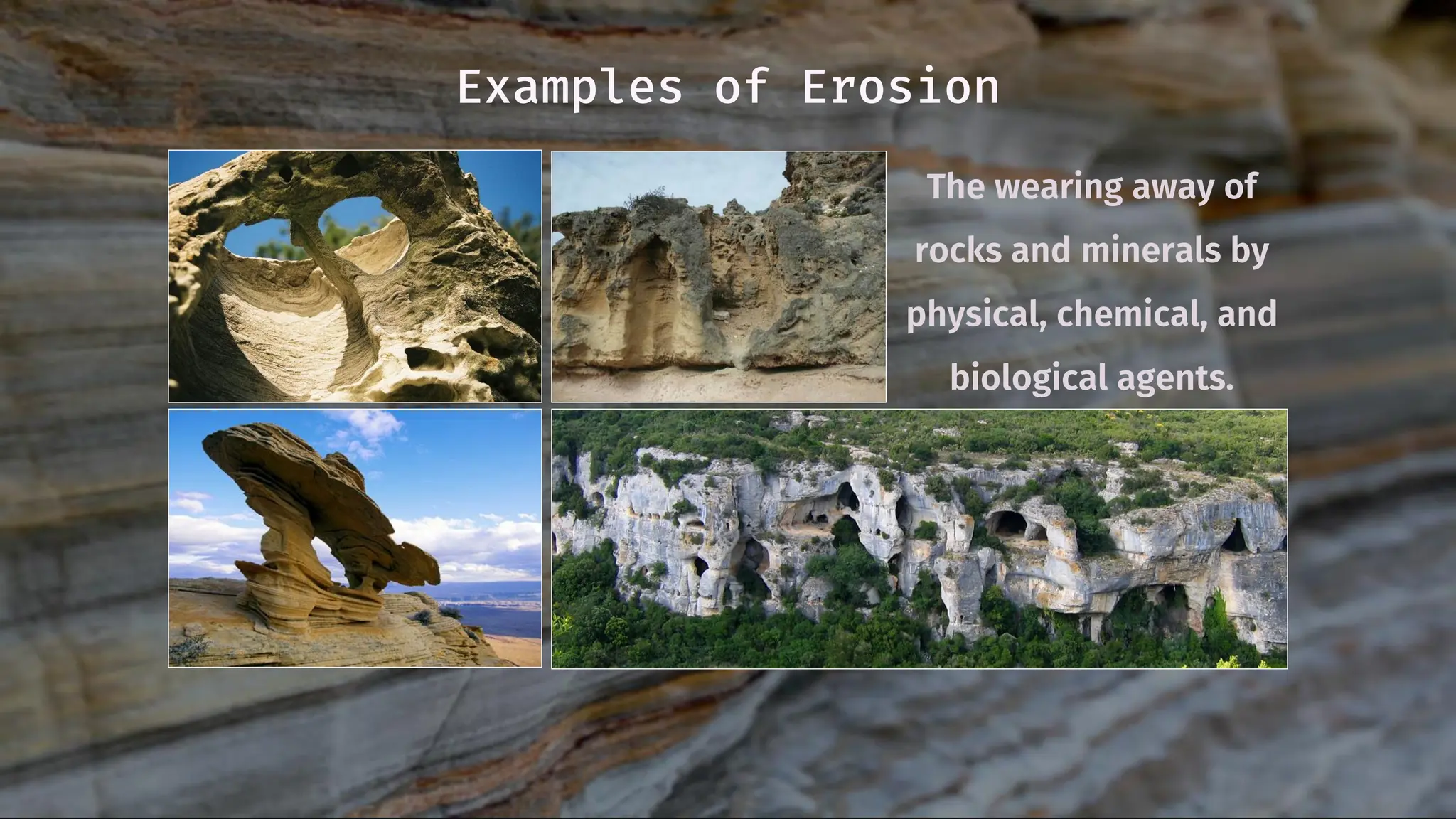

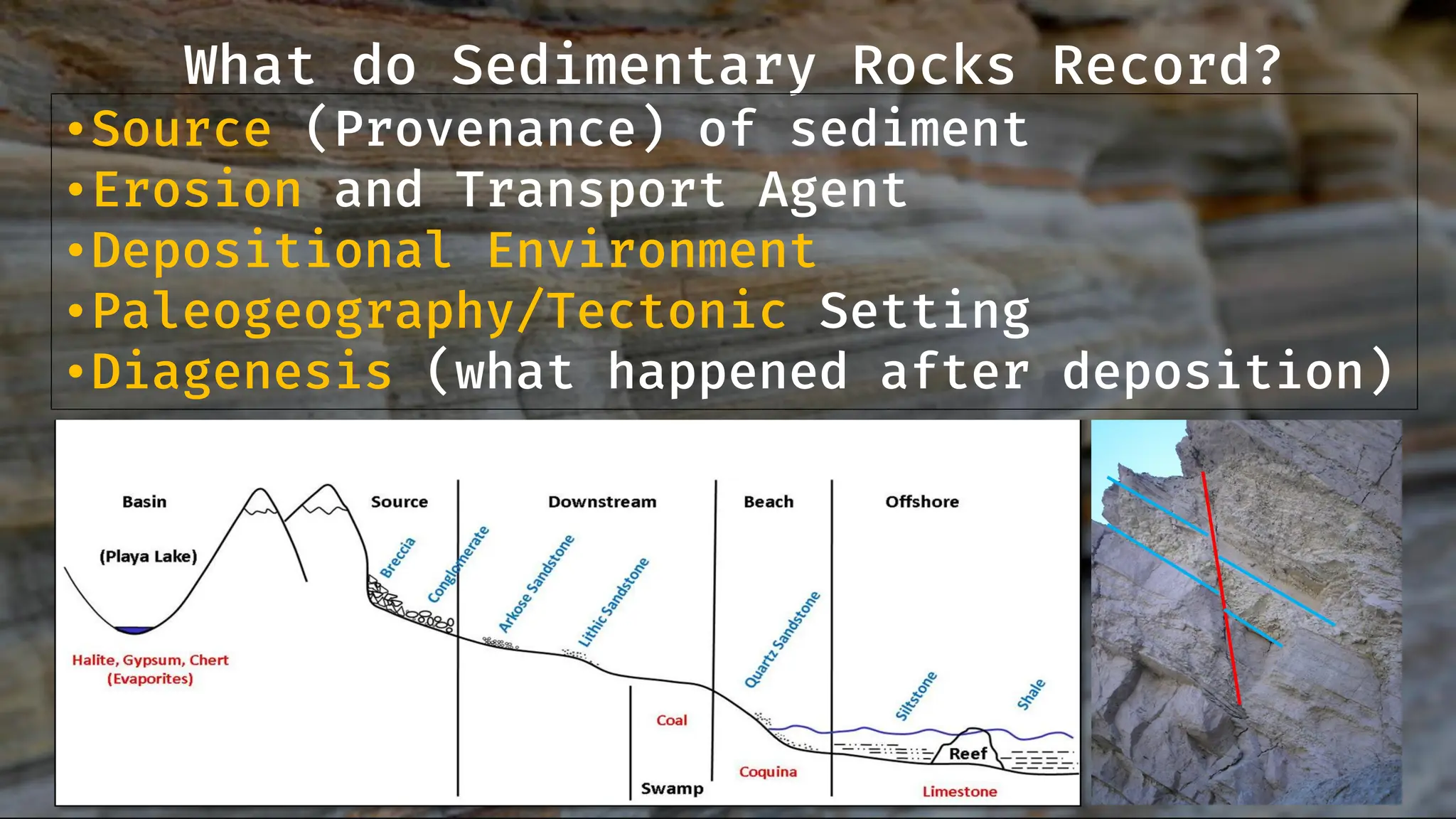

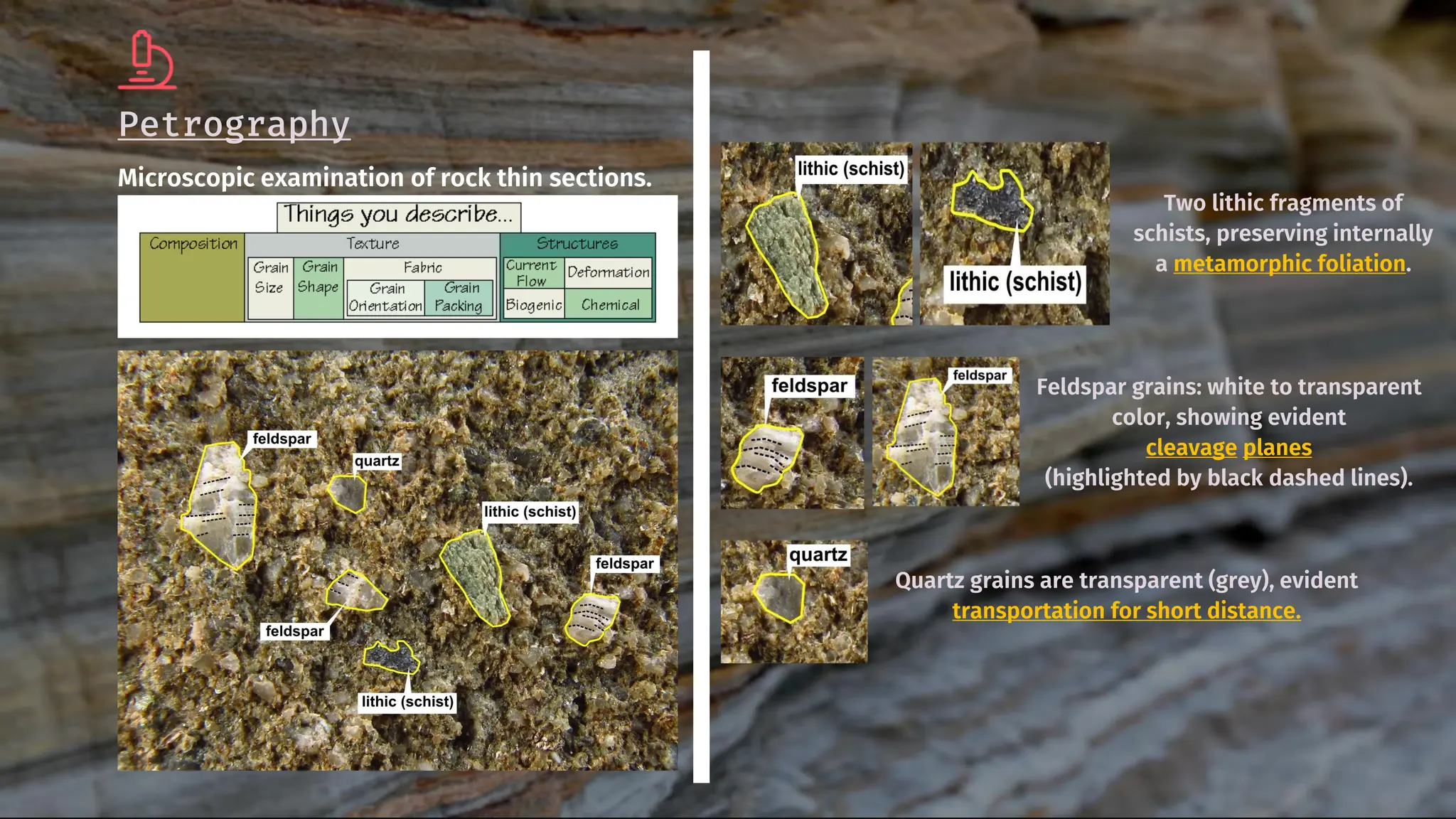

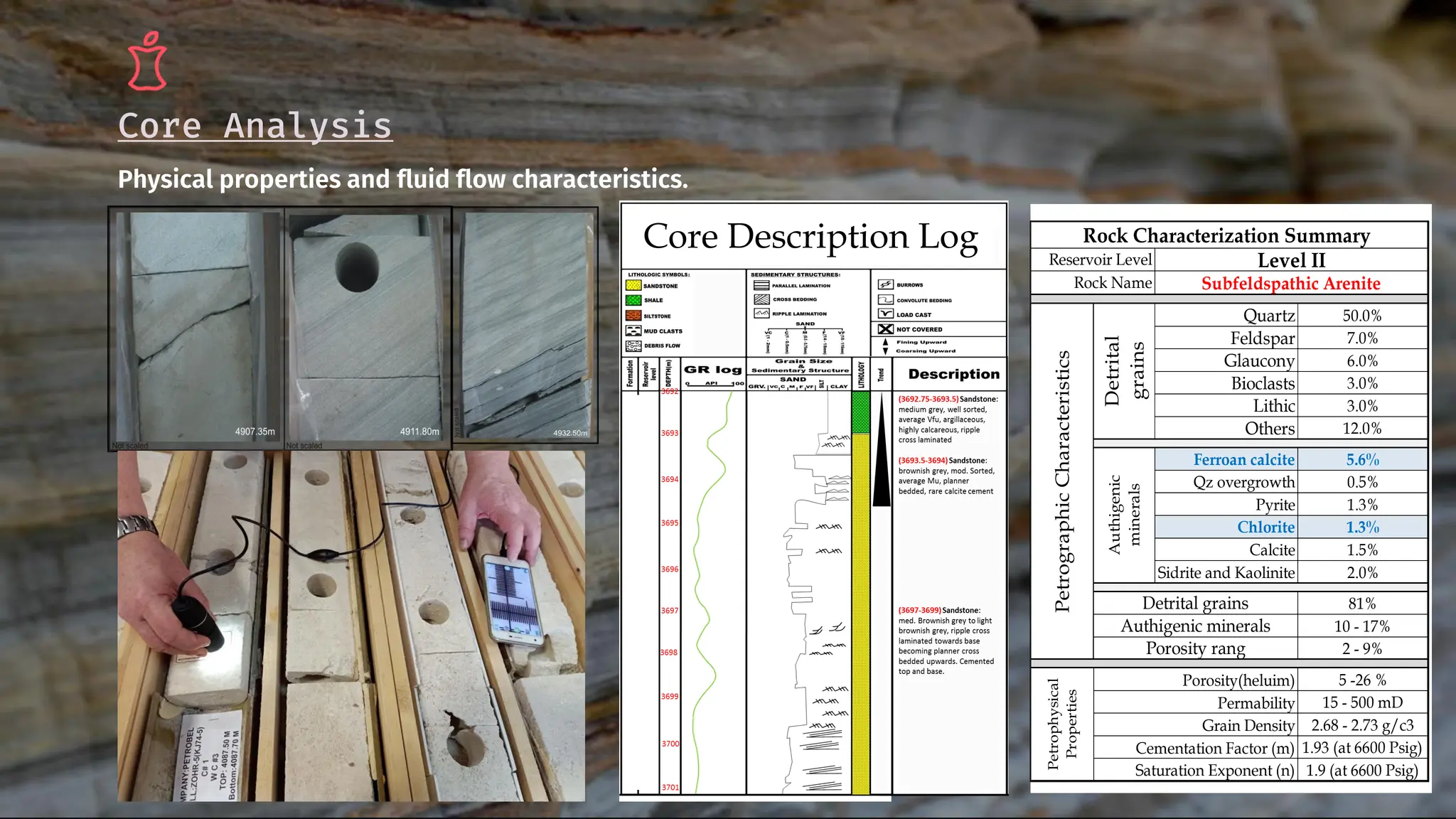

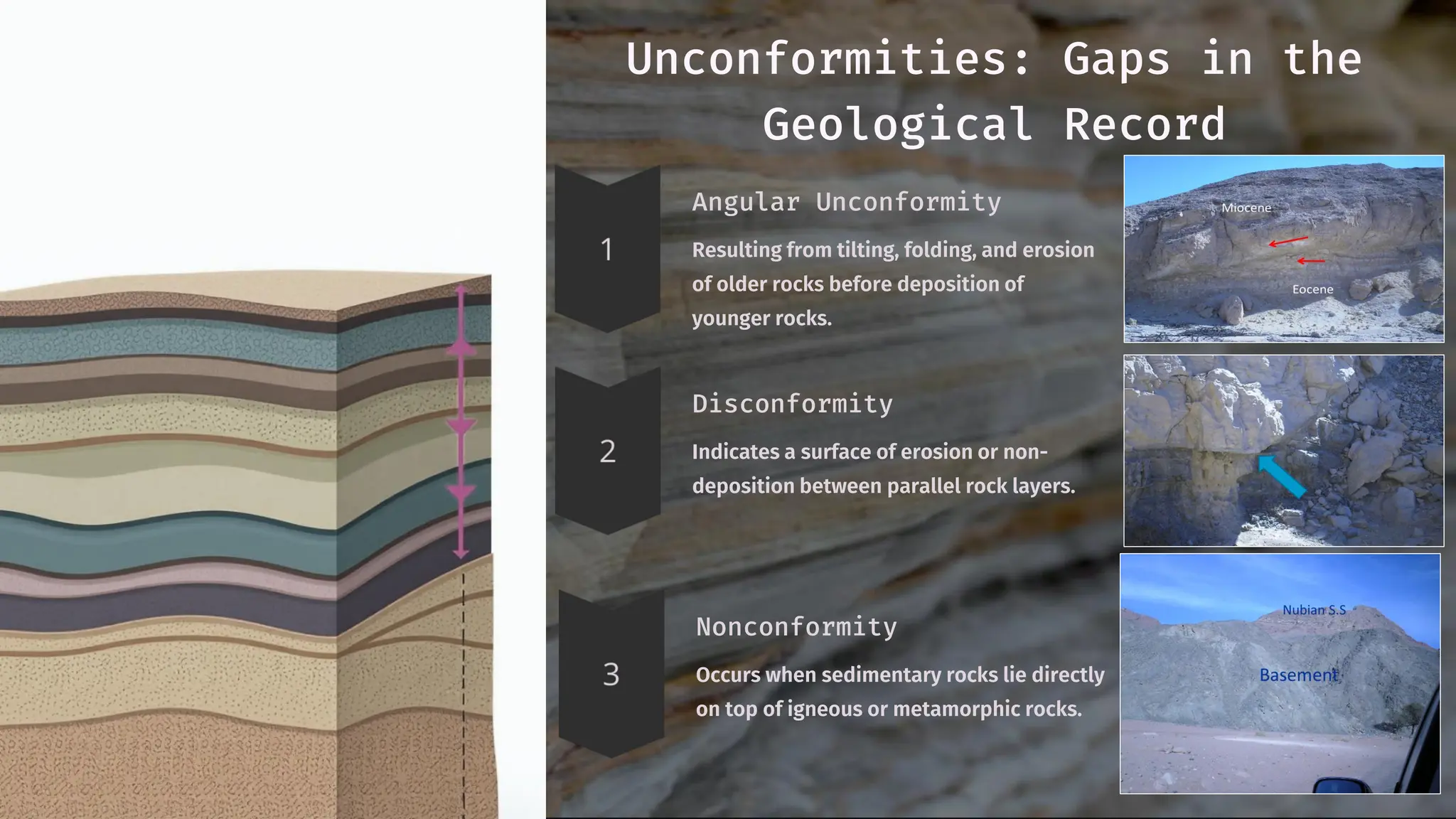

The document provides a comprehensive overview of sedimentology and stratigraphy, focusing on processes involved in the formation, transport, and deposition of sediments and their significance in various fields, such as petroleum geology and environmental science. It discusses the principles and applications of stratigraphy, including the study of rock layers and geological history, as well as sediment characteristics like texture, sorting, and structures that provide insights into past environments. Additionally, it covers sedimentary rock types, formation processes, and methods for analyzing sediments and stratigraphic correlations.