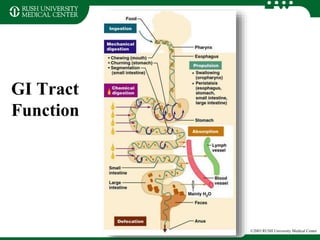

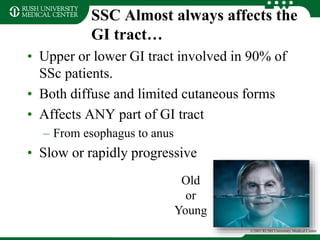

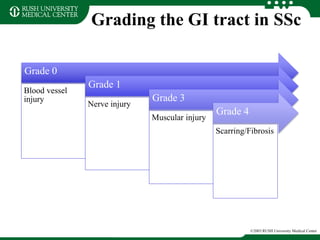

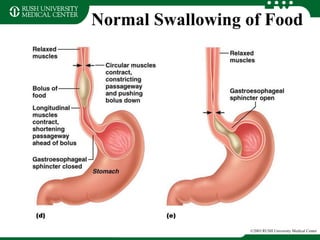

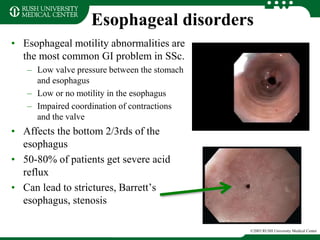

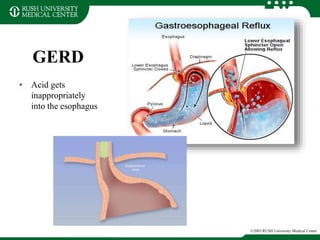

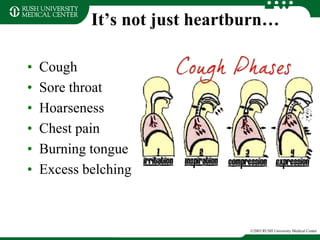

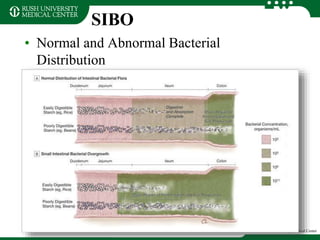

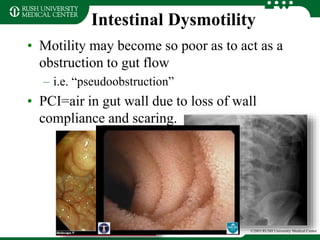

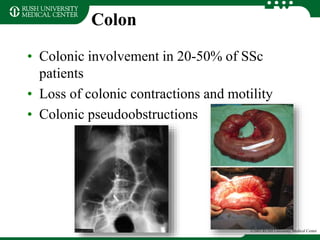

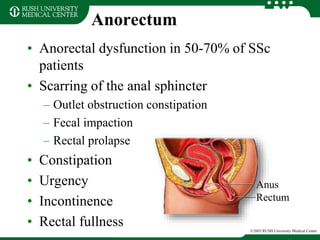

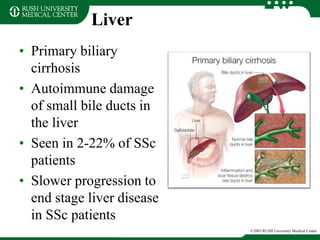

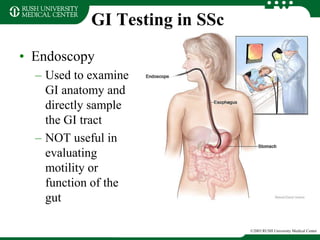

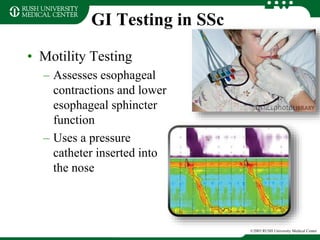

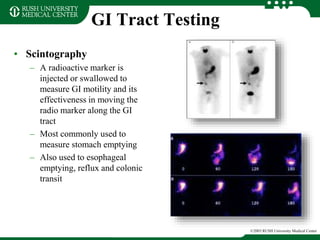

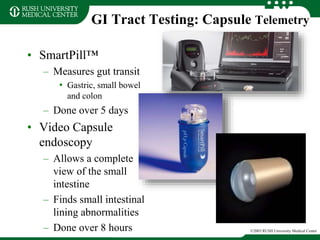

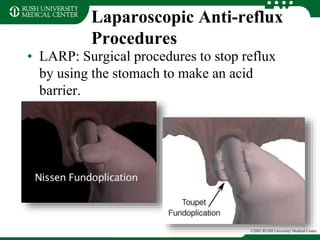

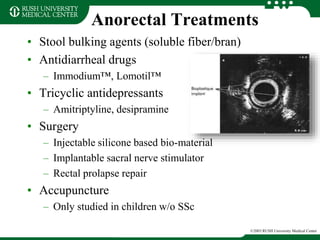

Scleroderma commonly affects the gastrointestinal tract in 90% of patients, causing problems through fibrosis and impaired motility. Common issues include acid reflux, delayed stomach emptying, bacterial overgrowth from small intestine immobility, and constipation from slowed colonic transit. Diagnosis involves tests to evaluate motility and function like endoscopy, pH testing, scintigraphy and breath tests. Treatment aims to control symptoms through dietary changes, acid suppression, prokinetics and antibiotics, though current options cannot stop progression of gastrointestinal fibrosis.