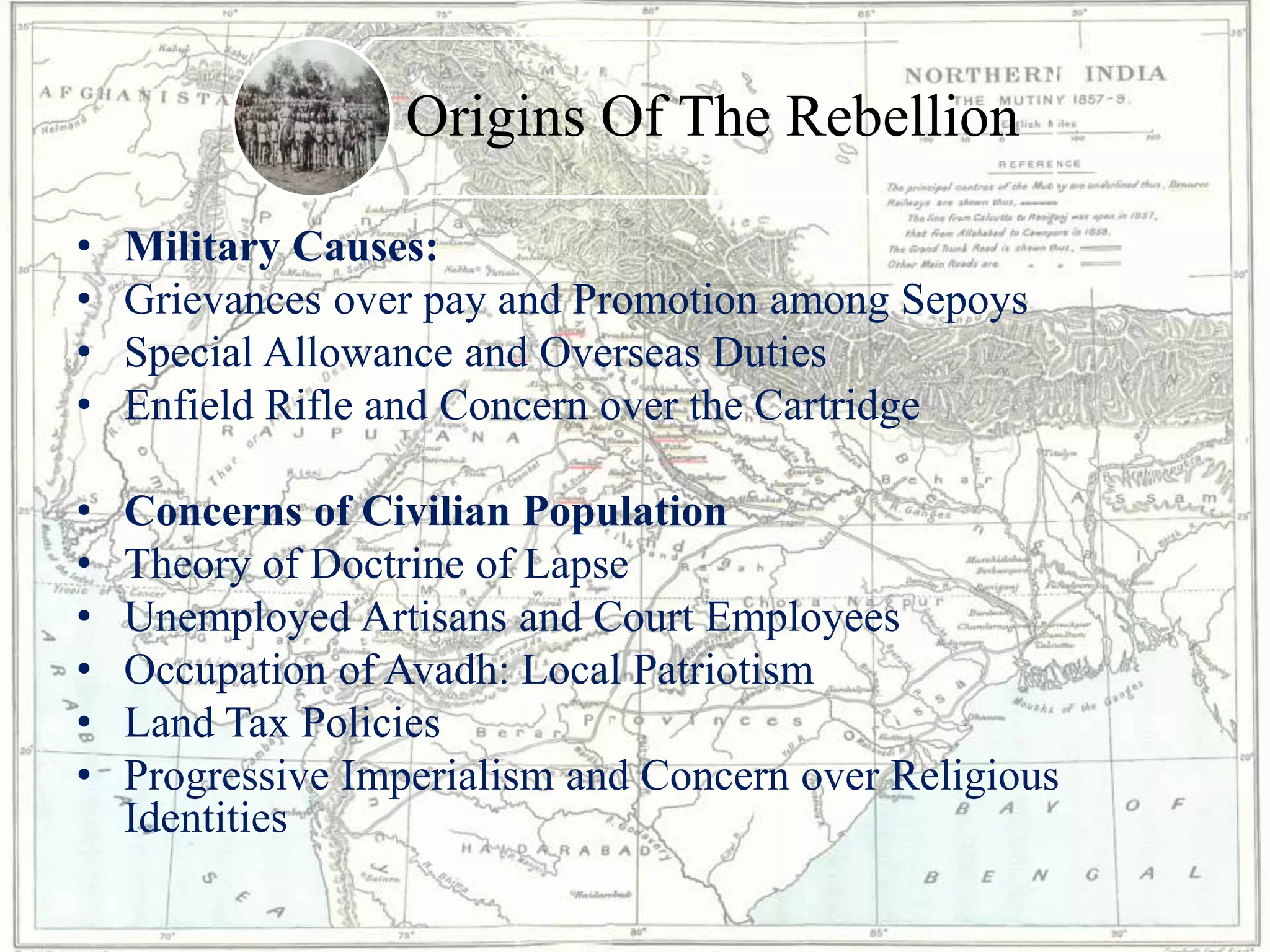

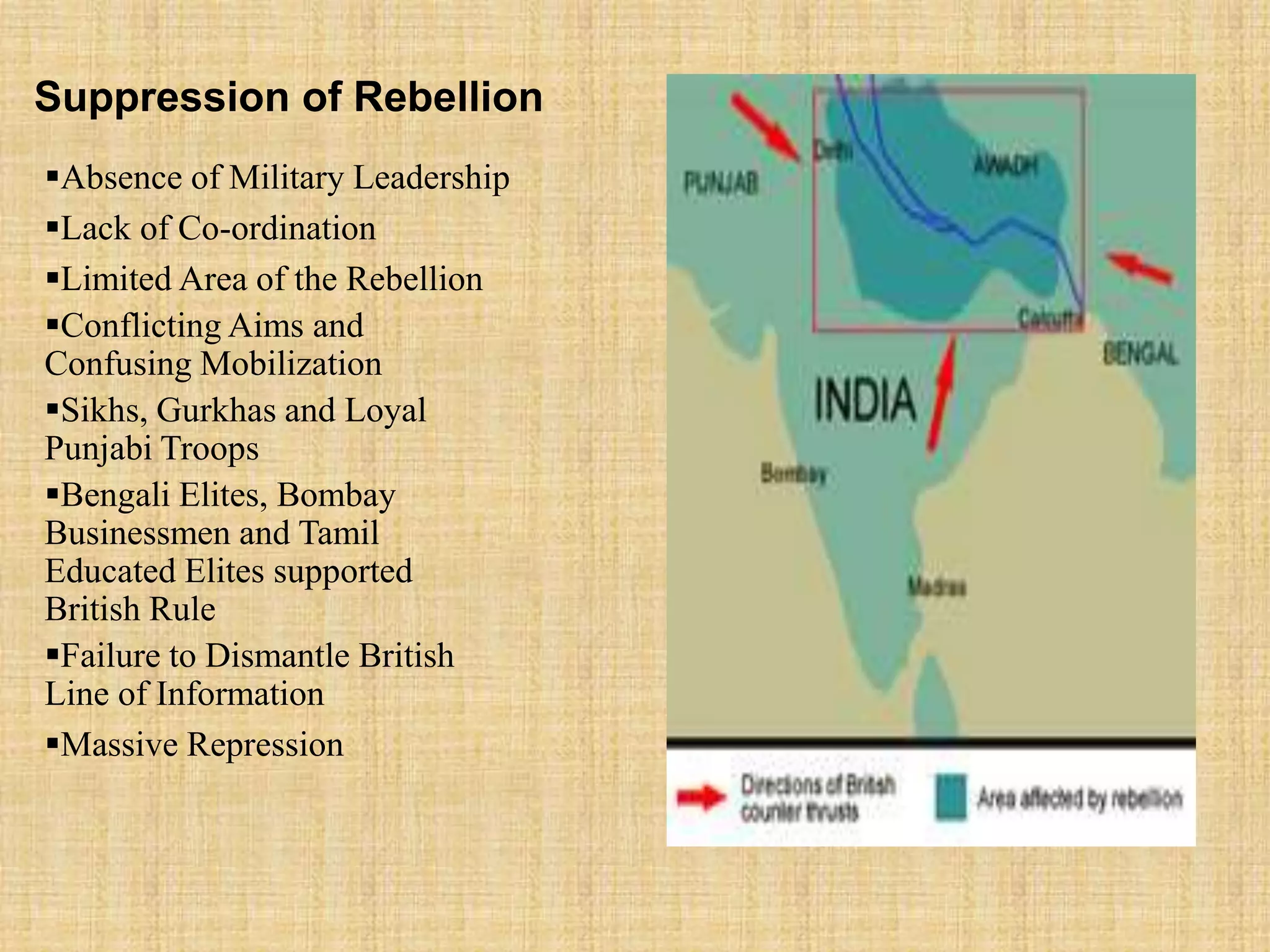

The document provides a detailed overview of the Rebellion of 1857 in India. It covers the origins, timeline, suppression, interpretations, patterns, and leadership of the rebellion. It also discusses the roles of sepoys, peasants, artisans, and the state of Awadh in the revolt. The document outlines the end of Mughal rule, grievances against British colonialism, the search for alternative power structures, and images/depictions of the rebellion in paintings, prints and films. It concludes with the administrative changes the British implemented in response like new laws, policies of repression, and portraying the rebellion as a mutiny to consolidate imperial power.

![THERebellionof 1857

Made by

Ranjeet

[9160392]

Piyush

[9160390]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rebellionof1857-150508060936-lva1-app6891/75/Rebellion-of-1857-1-2048.jpg)