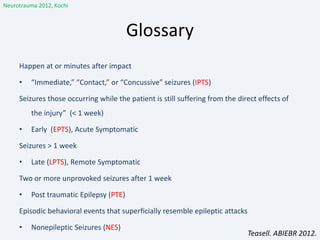

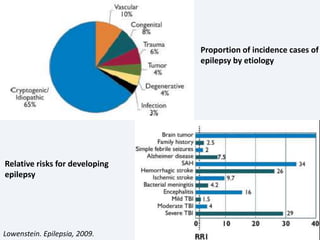

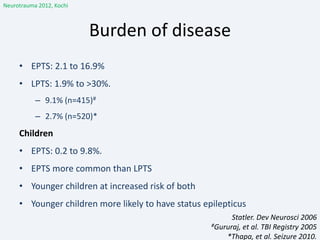

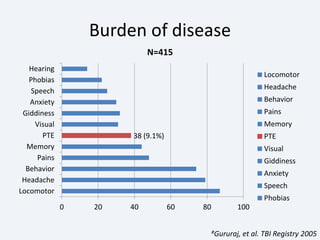

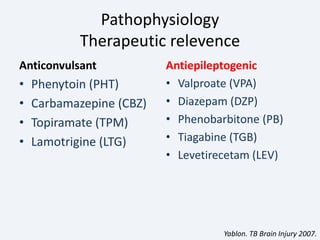

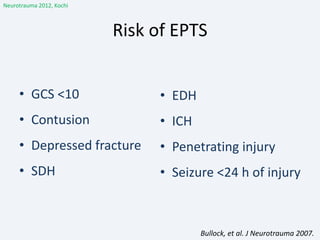

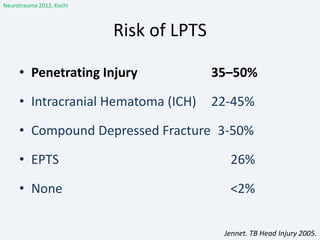

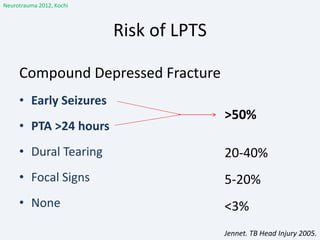

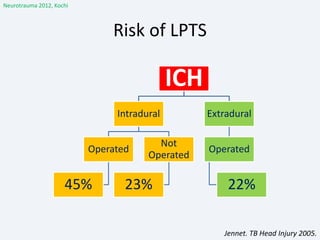

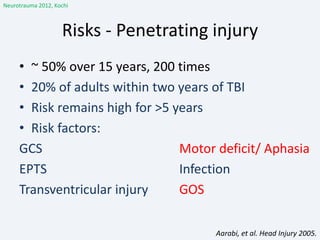

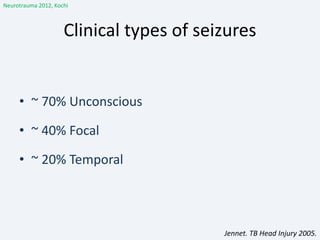

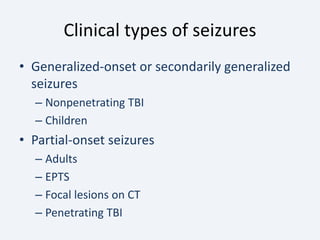

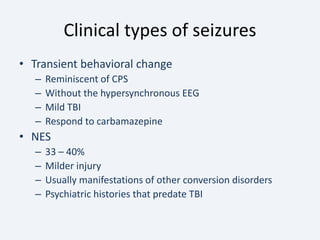

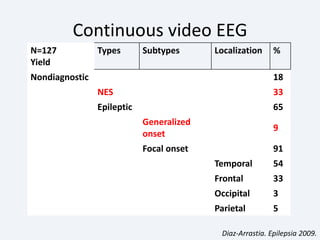

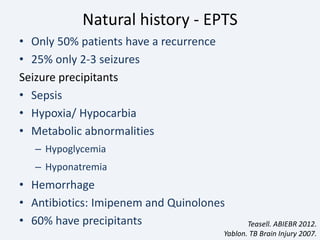

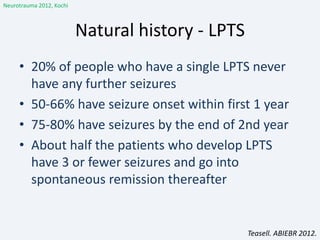

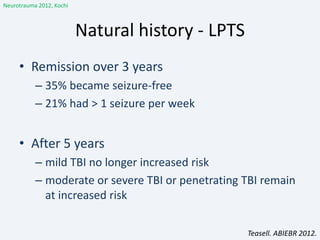

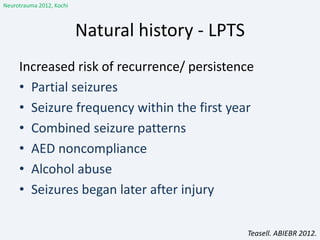

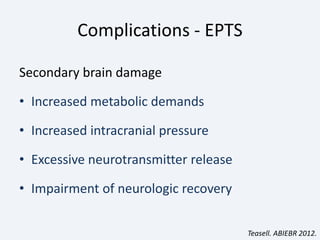

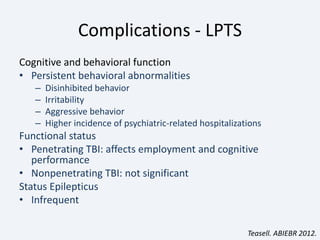

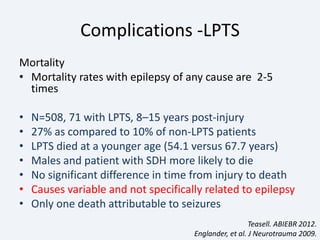

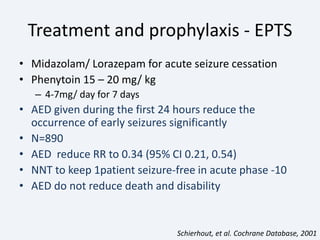

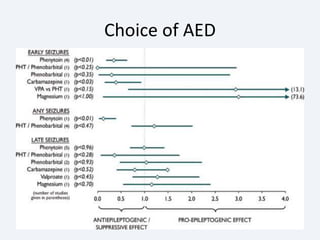

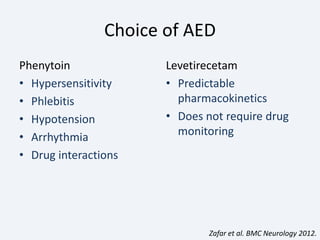

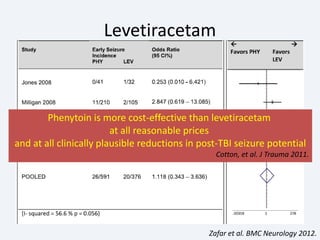

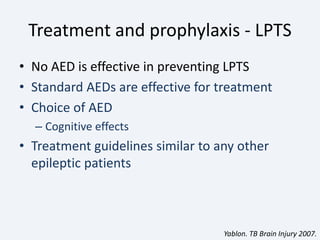

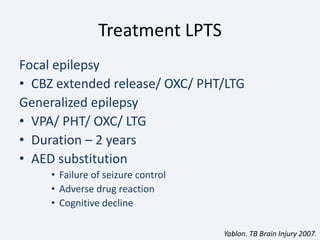

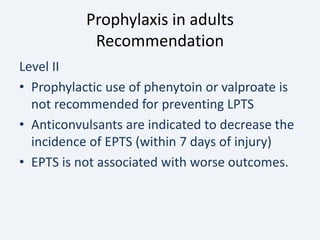

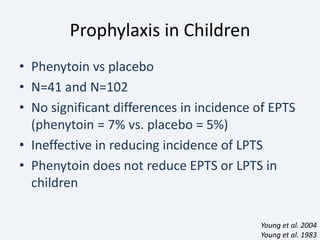

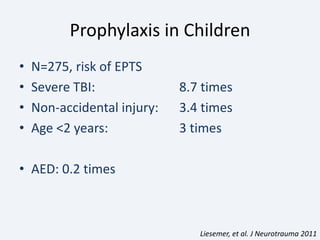

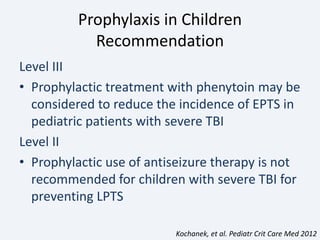

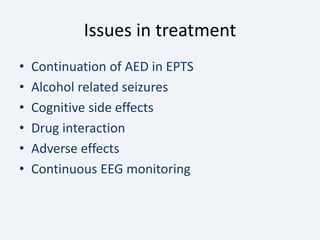

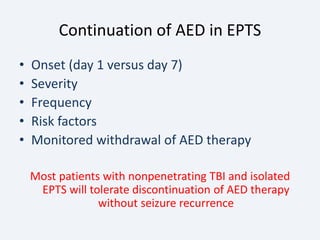

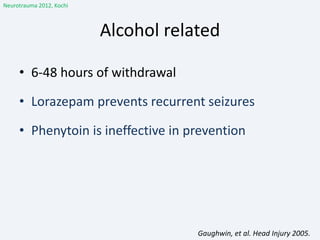

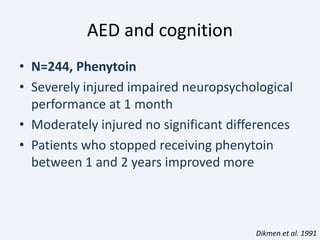

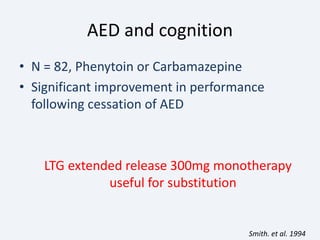

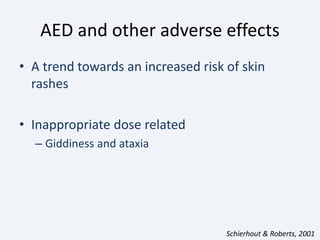

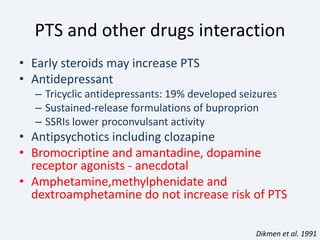

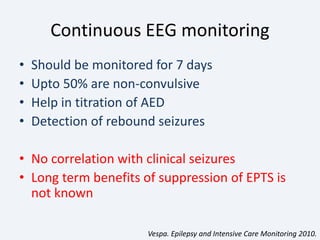

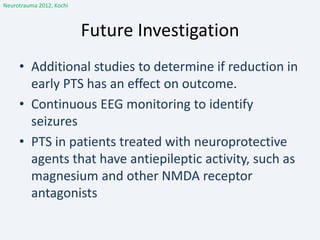

The document discusses post-traumatic seizures (PTS), categorizing them into immediate, early, late, and post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) with varying incidence rates based on age and type of injury. It covers the pathophysiology, risks of early and late seizures, their clinical types, natural history, complications, treatment options, and prophylactic measures. The document highlights the importance of monitoring and potential future investigations into effective treatments and outcomes related to PTS.