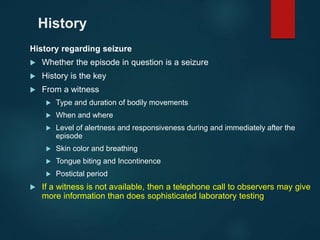

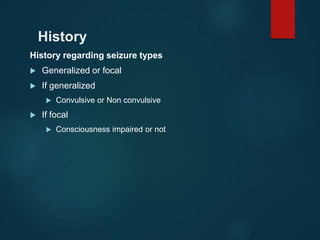

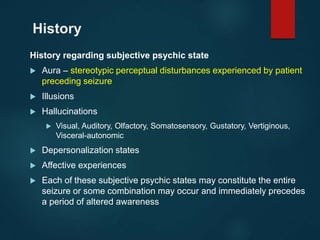

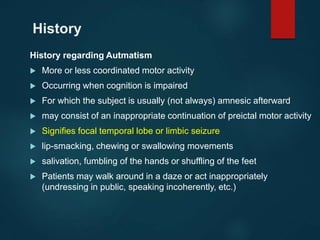

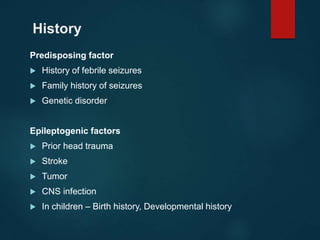

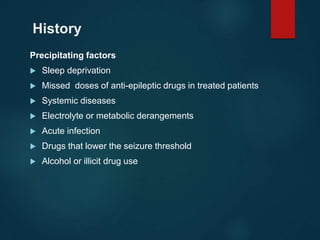

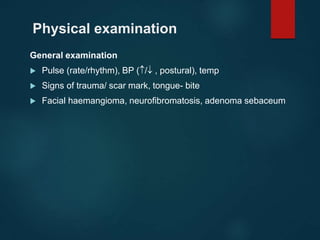

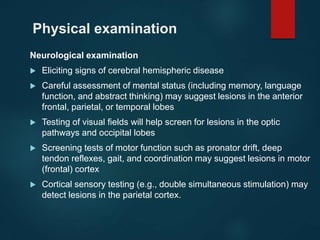

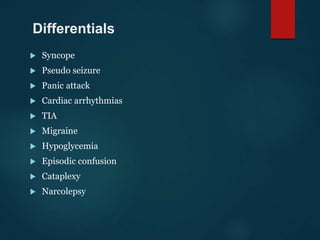

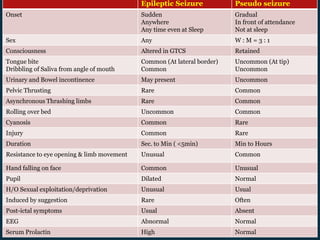

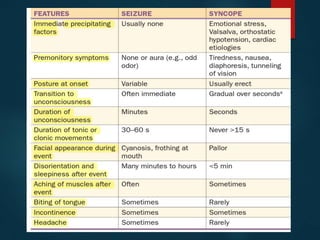

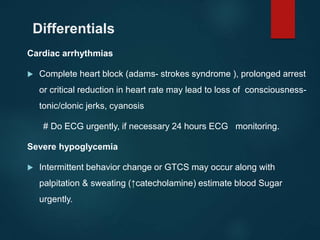

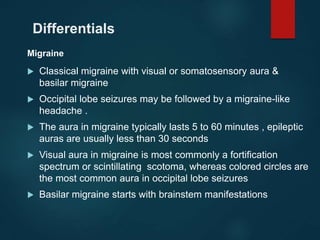

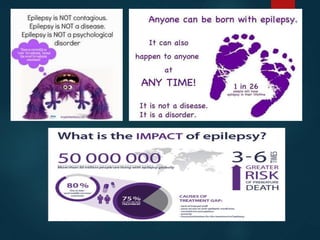

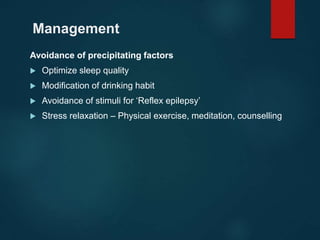

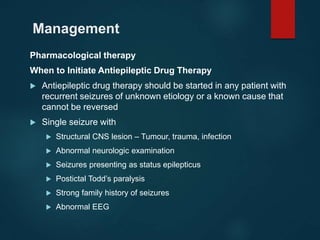

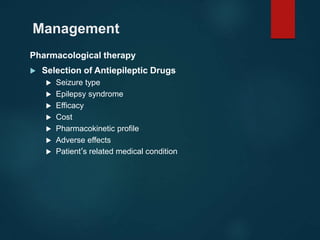

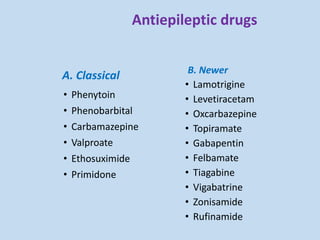

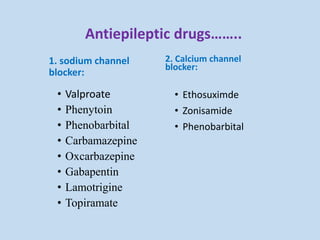

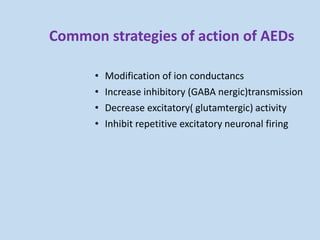

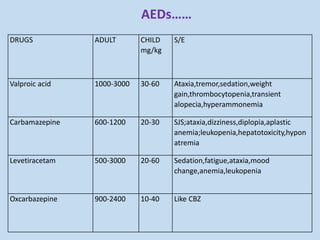

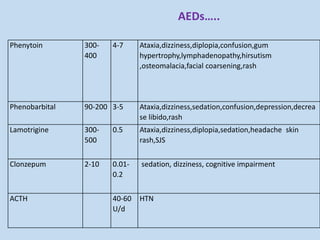

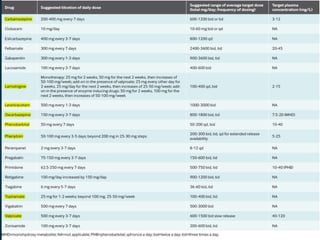

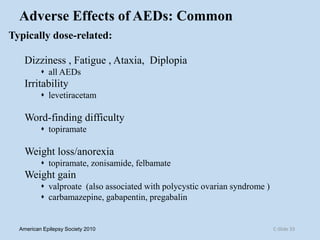

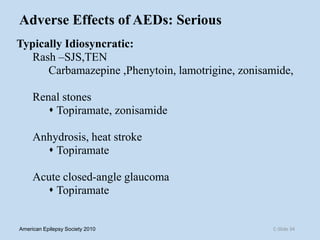

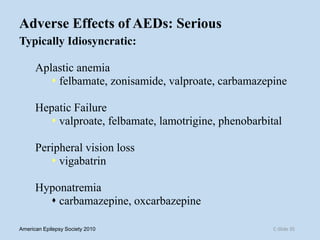

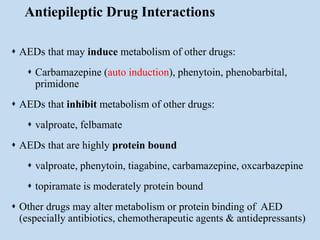

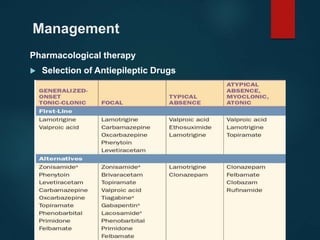

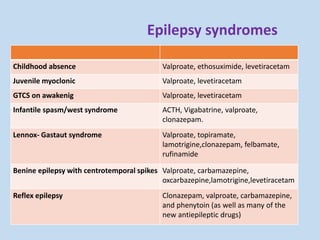

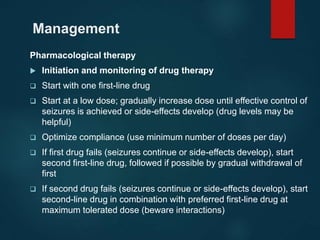

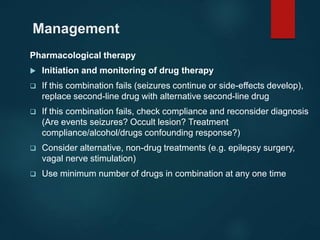

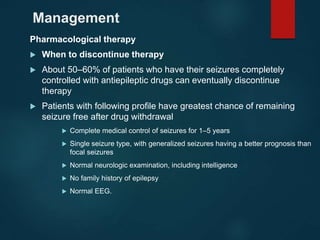

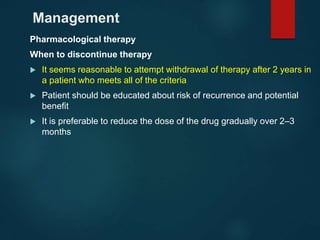

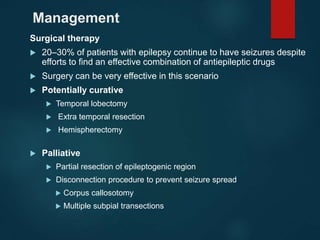

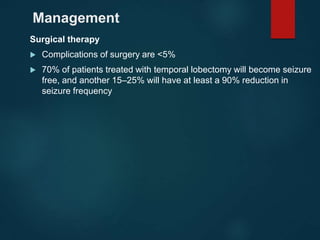

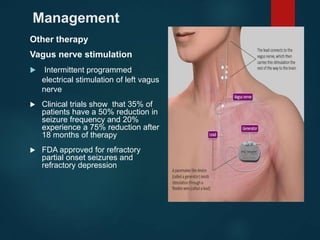

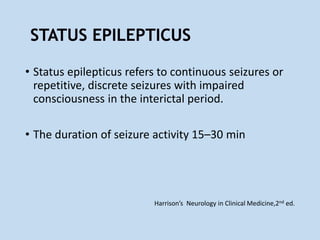

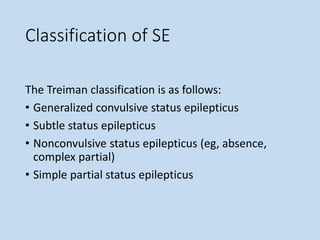

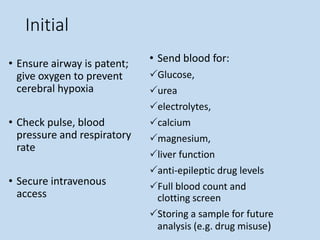

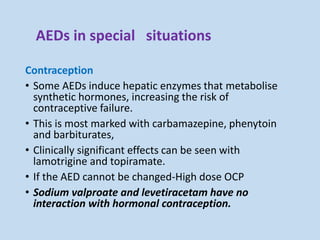

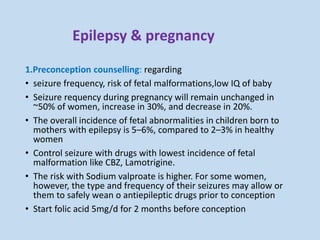

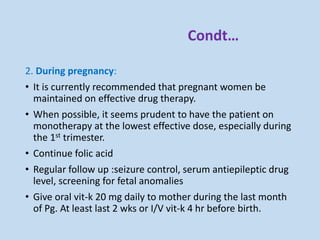

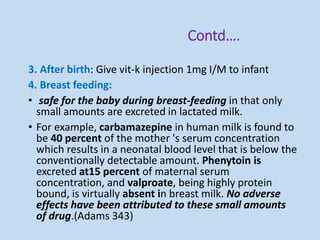

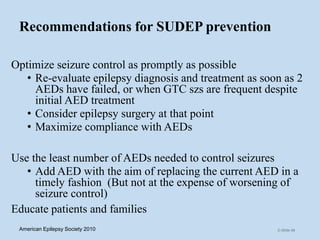

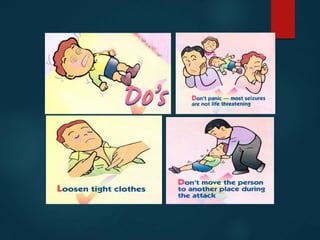

This document outlines the approach and management of epilepsy. It discusses taking a thorough history, including details of seizure episodes, predisposing factors, and precipitants. A physical exam focuses on neurological assessment. Differential diagnoses include syncope, pseudoseizures, and cardiac arrhythmias. Investigations include EEG. Management involves patient education, treating underlying causes, avoiding triggers, pharmacological therapy including multiple antiepileptic drugs, and in some cases surgery. Antiepileptic drugs work via various mechanisms and have potential adverse effects requiring monitoring.