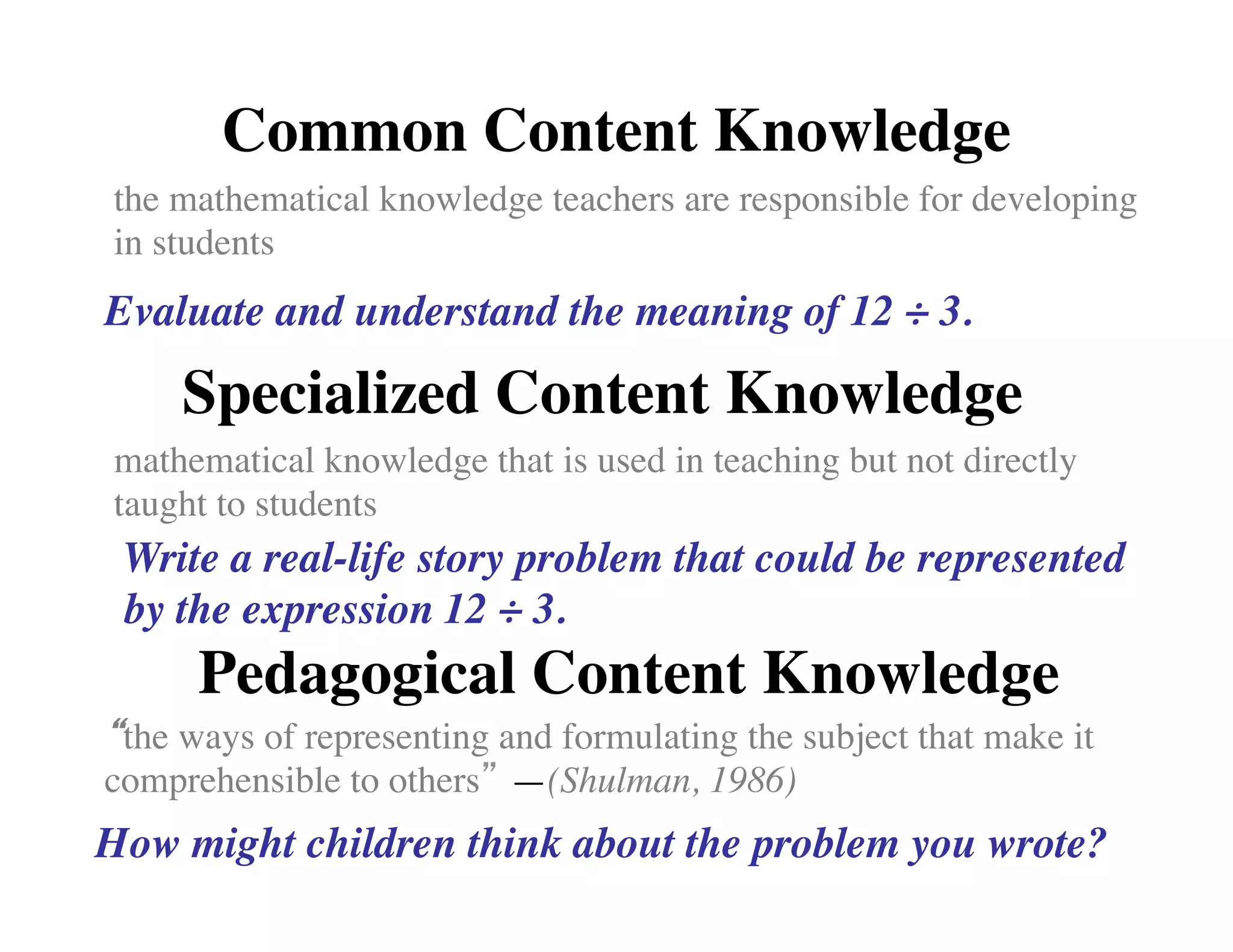

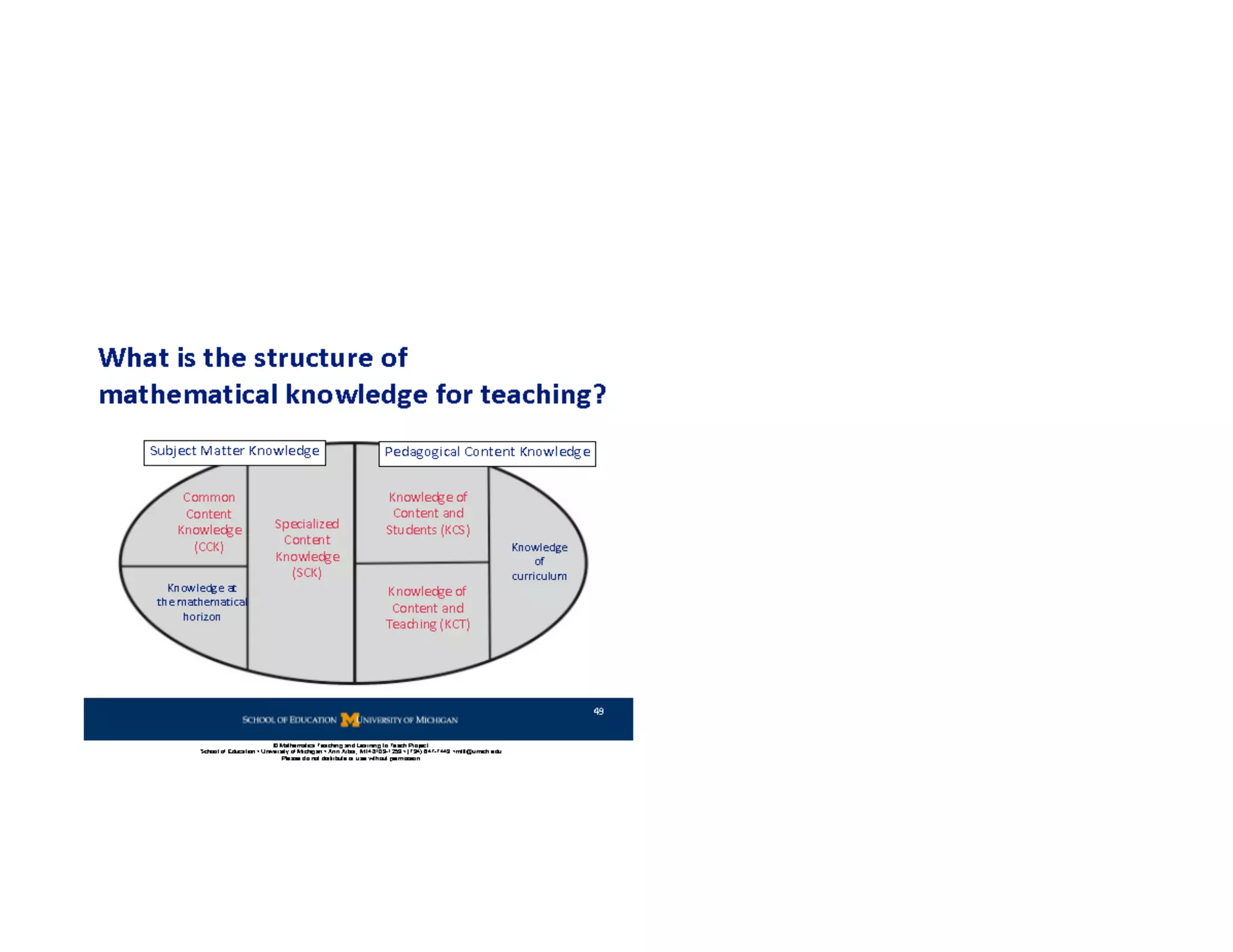

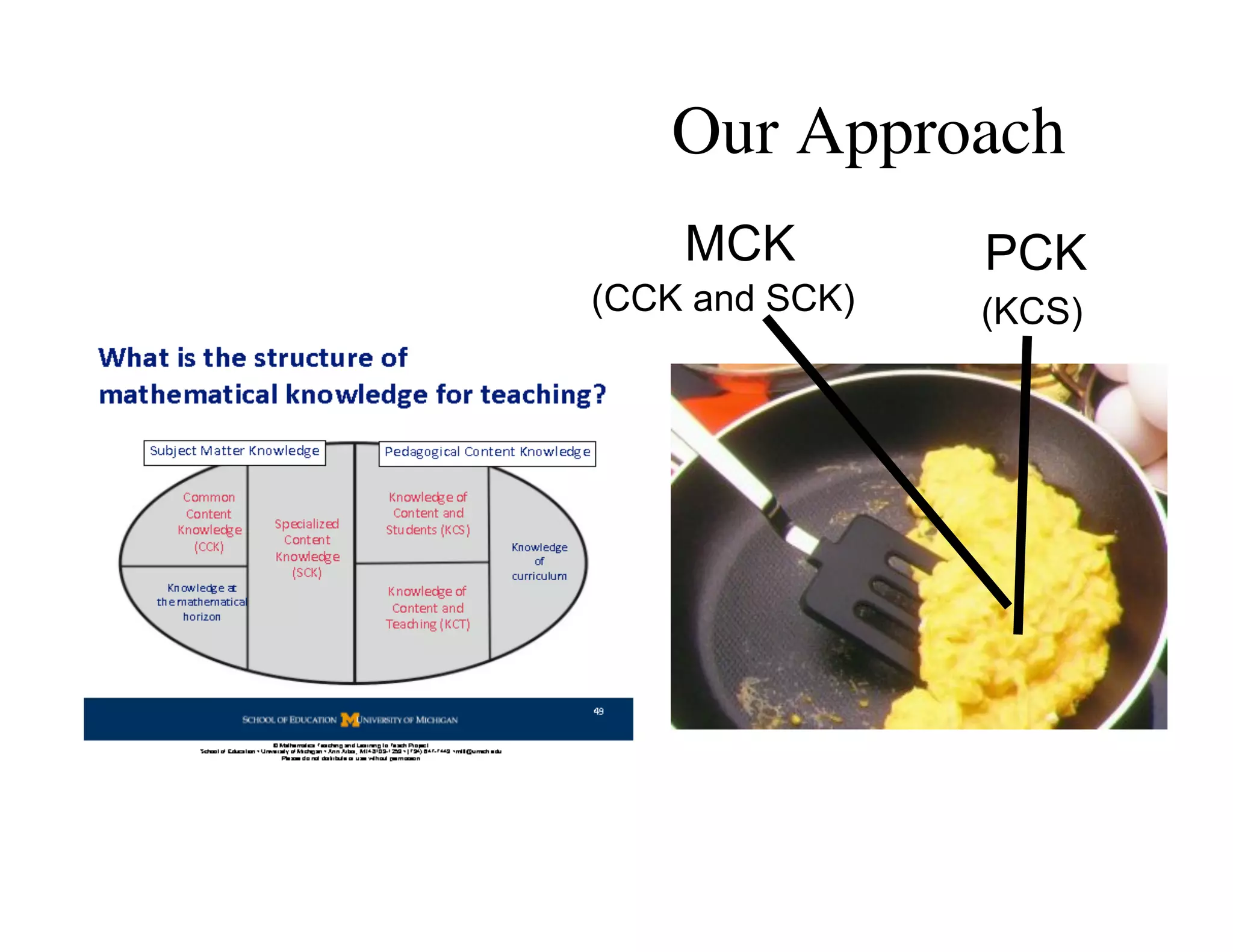

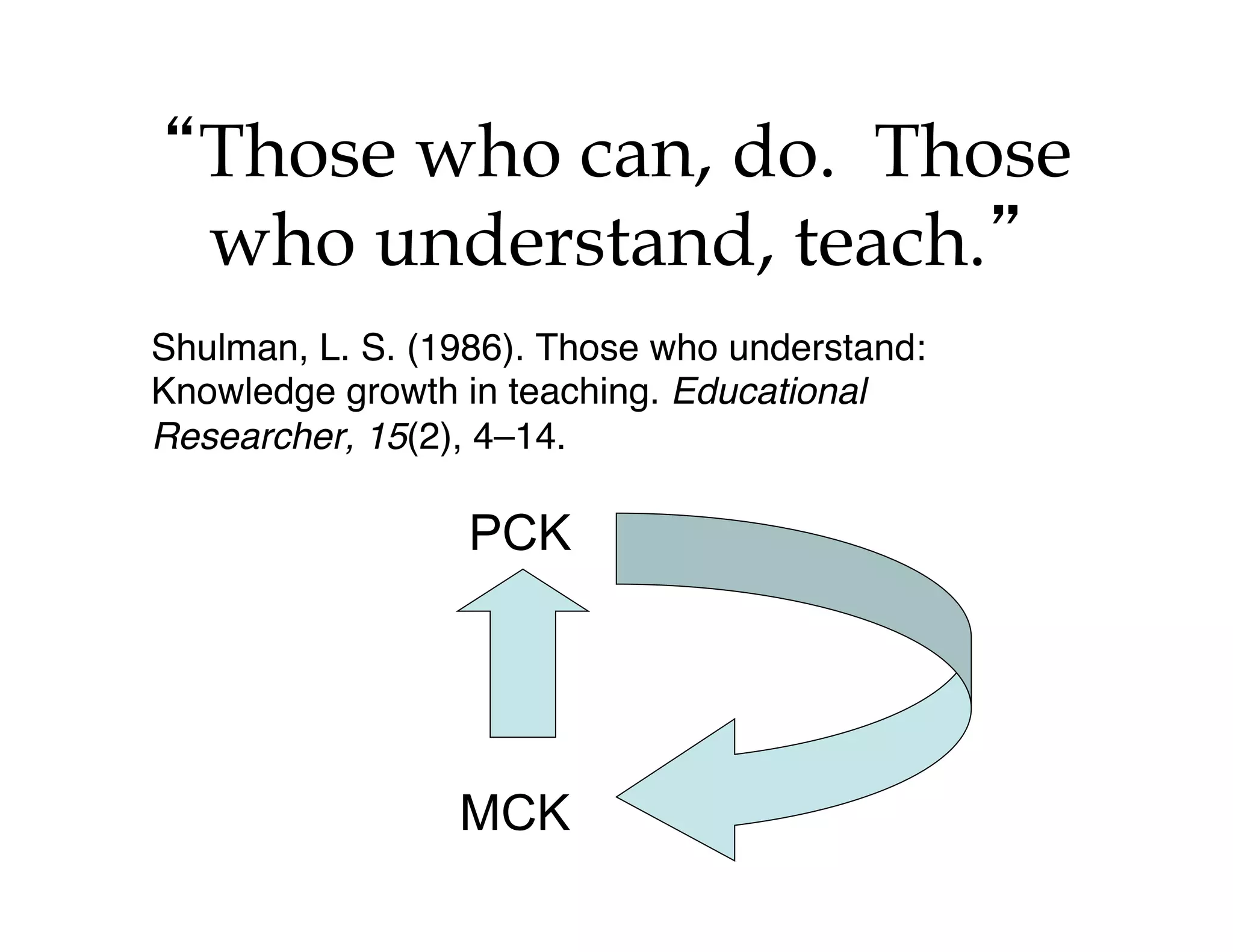

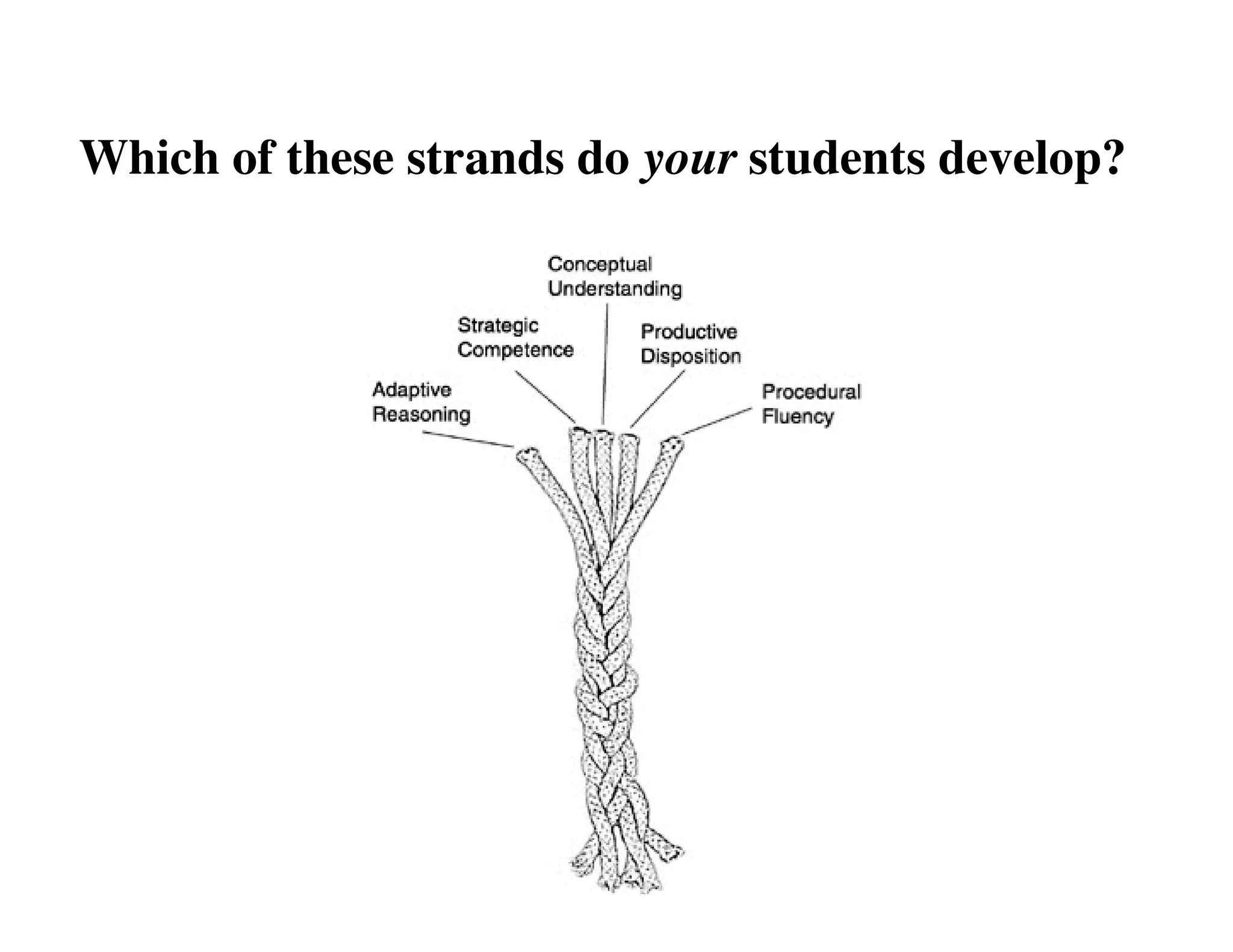

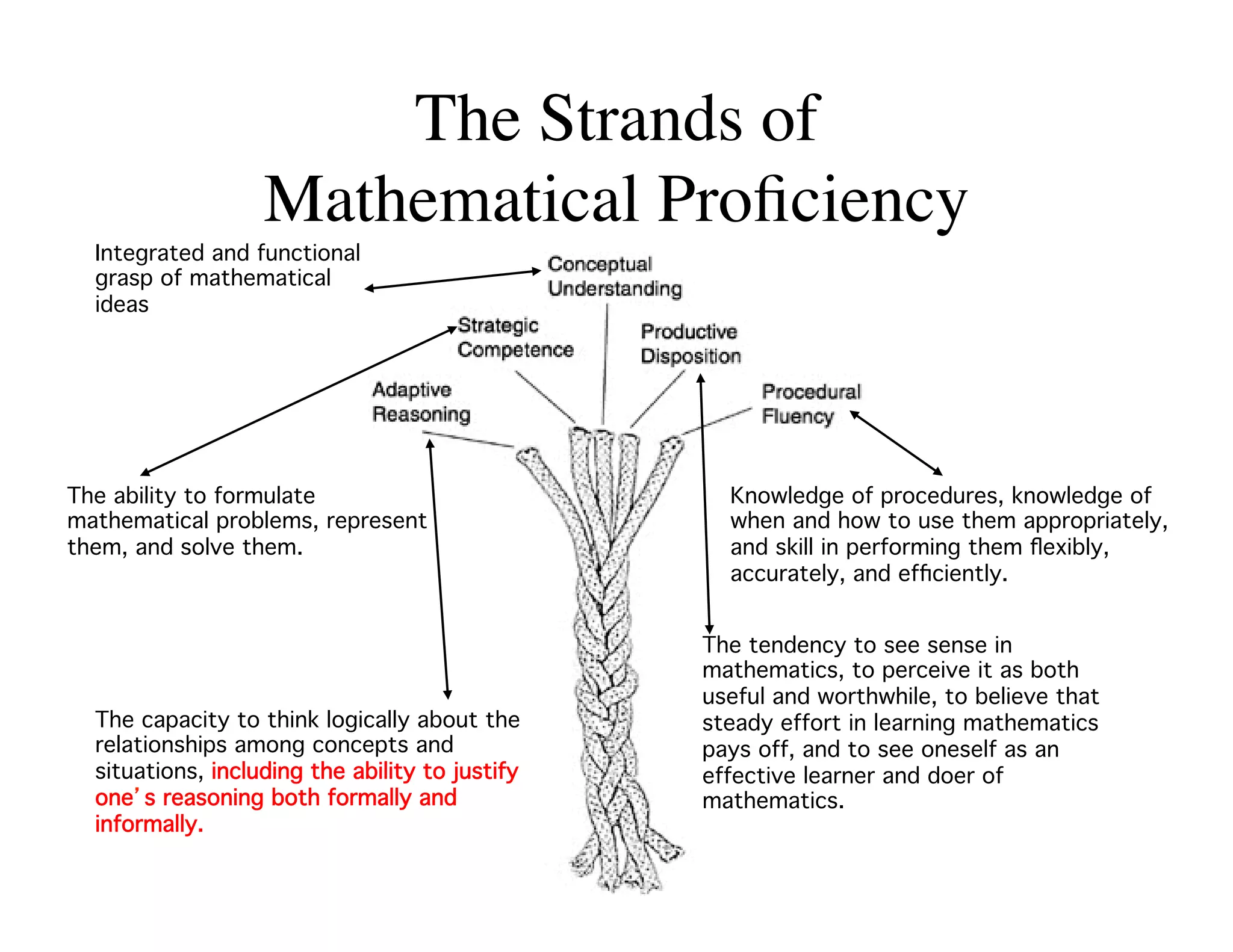

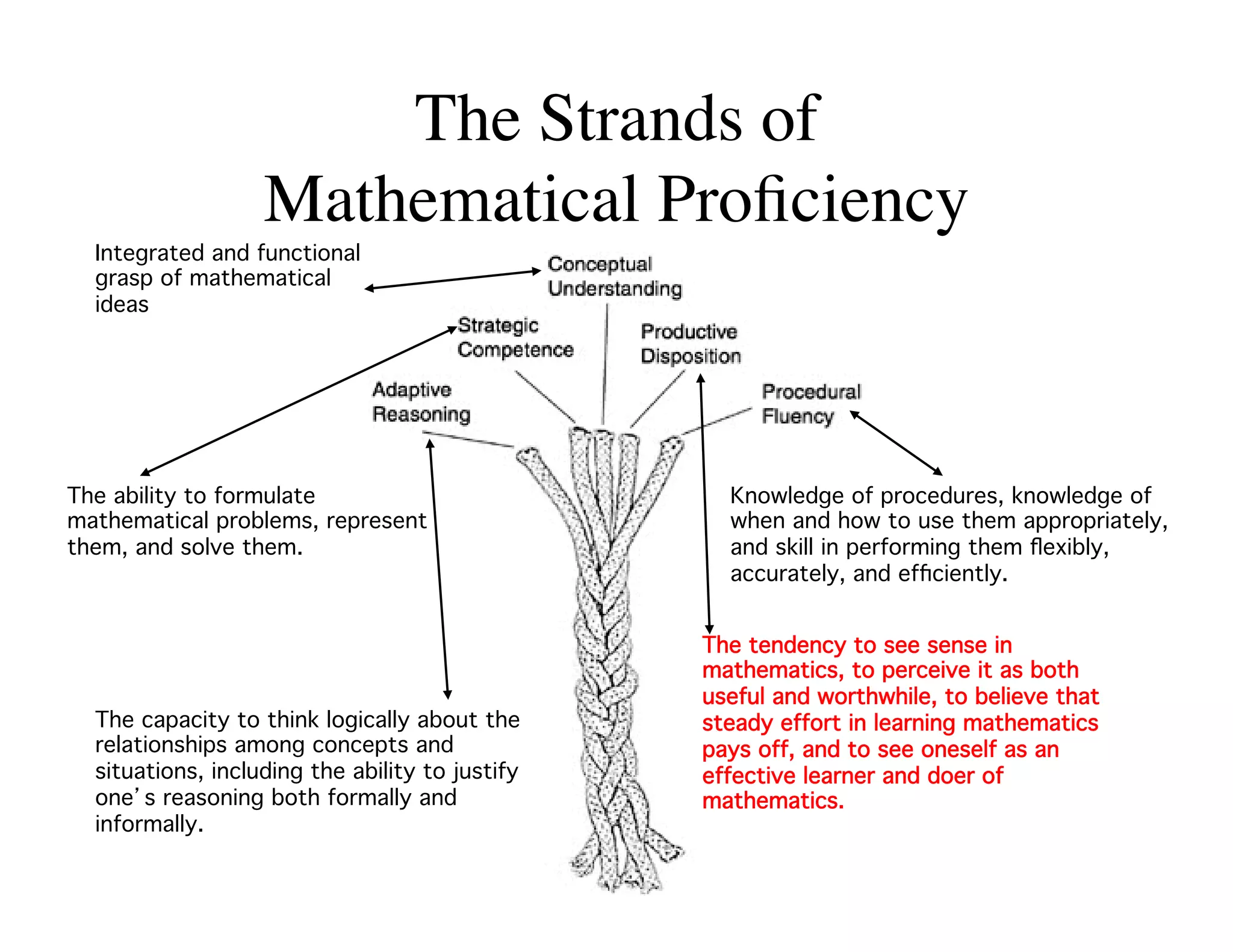

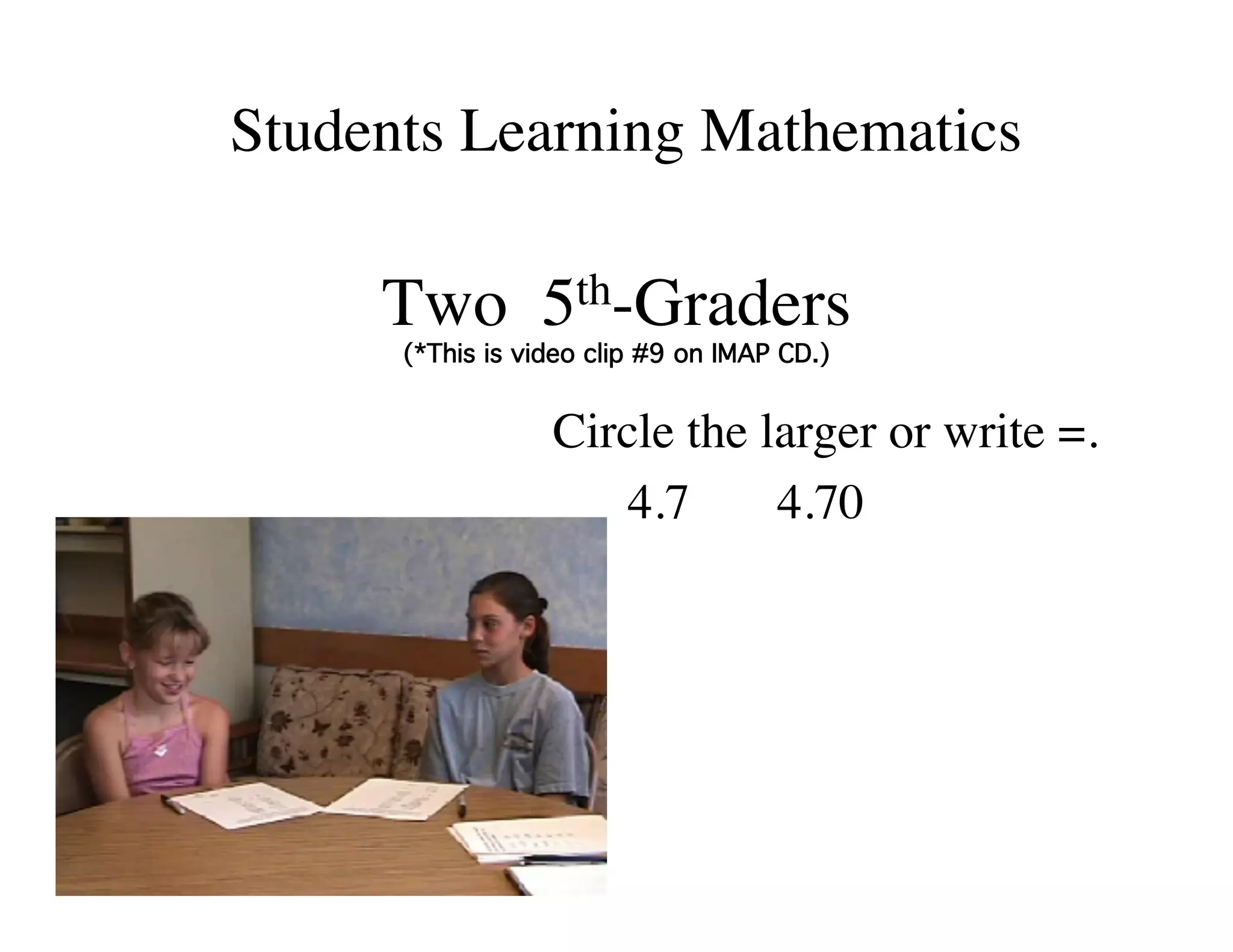

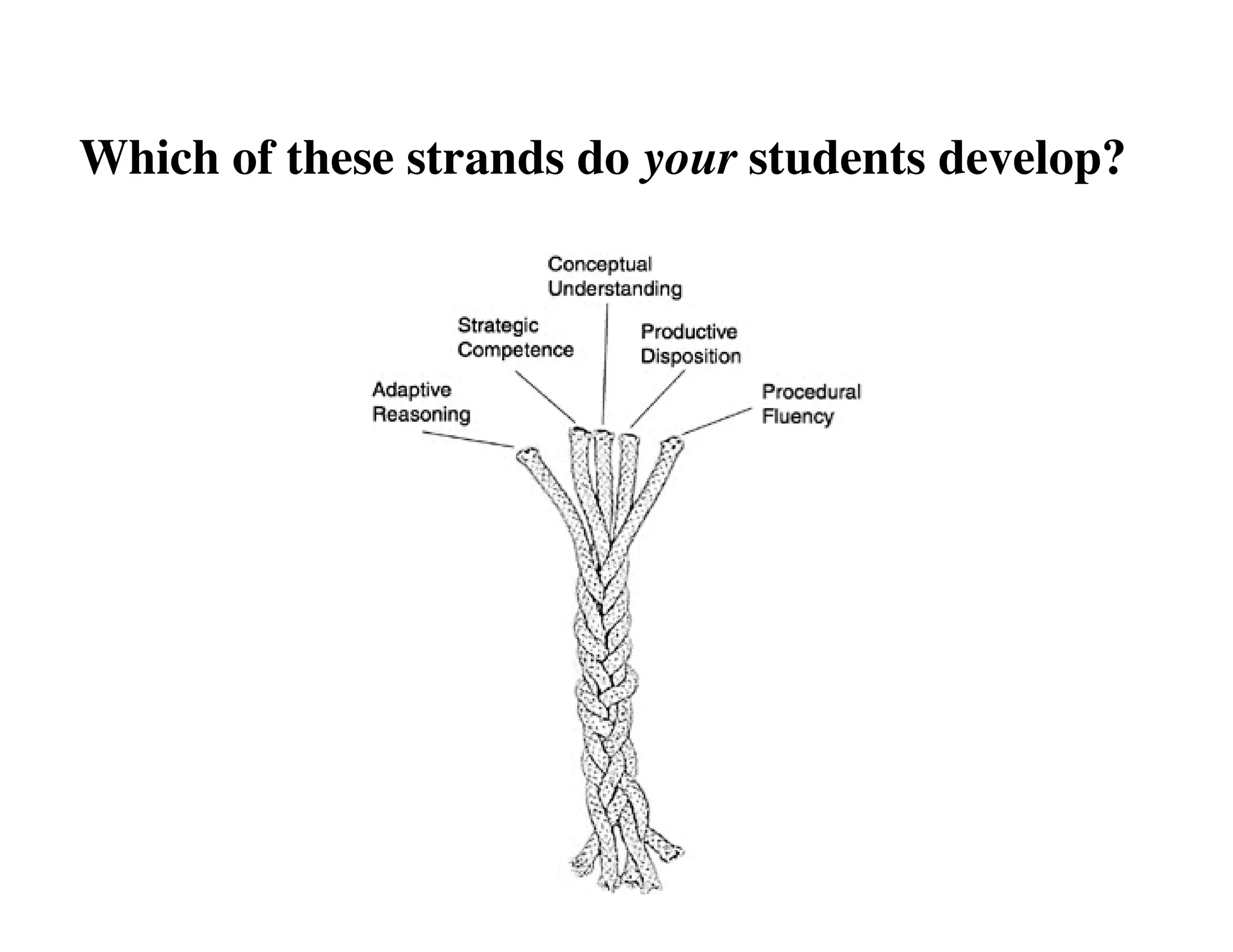

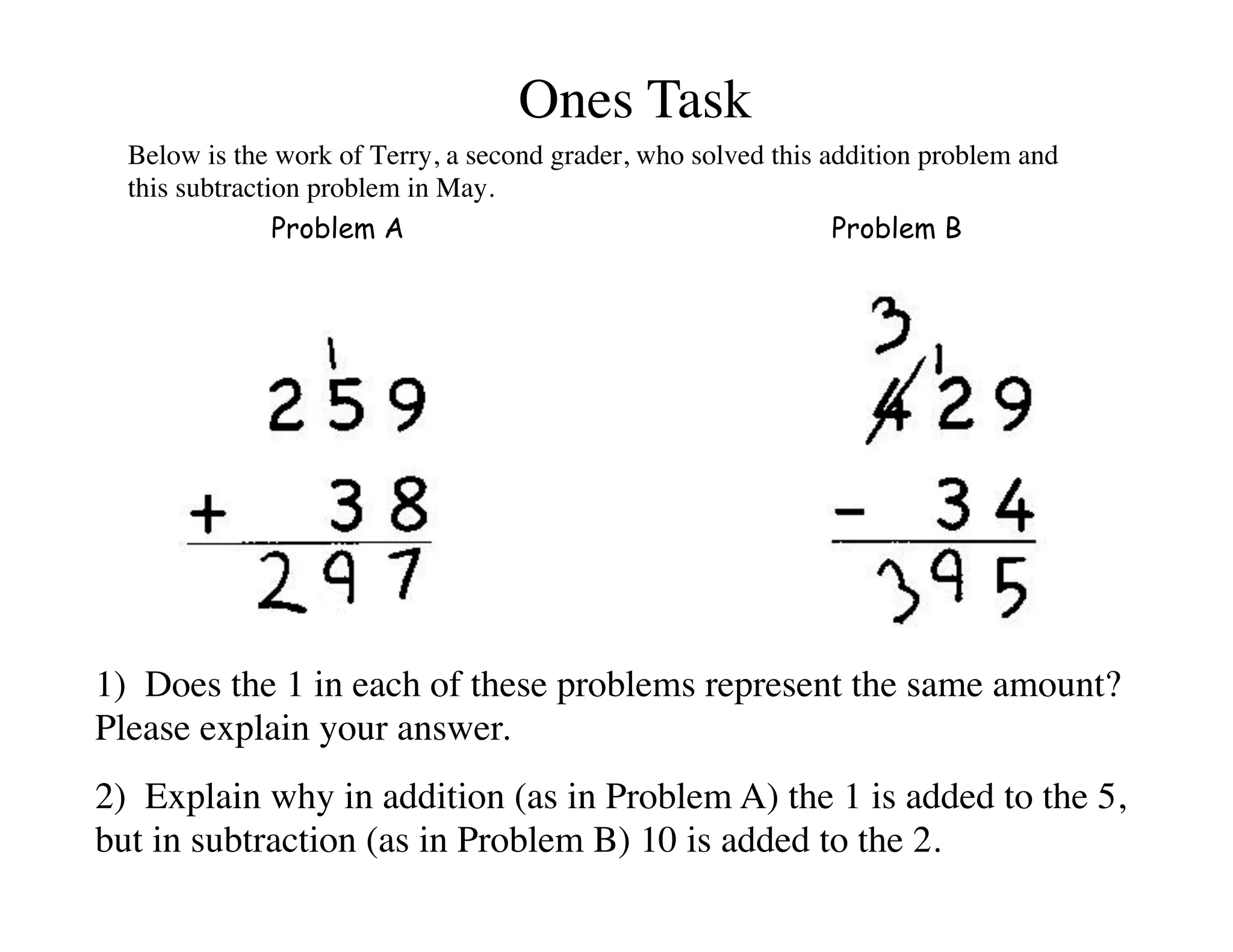

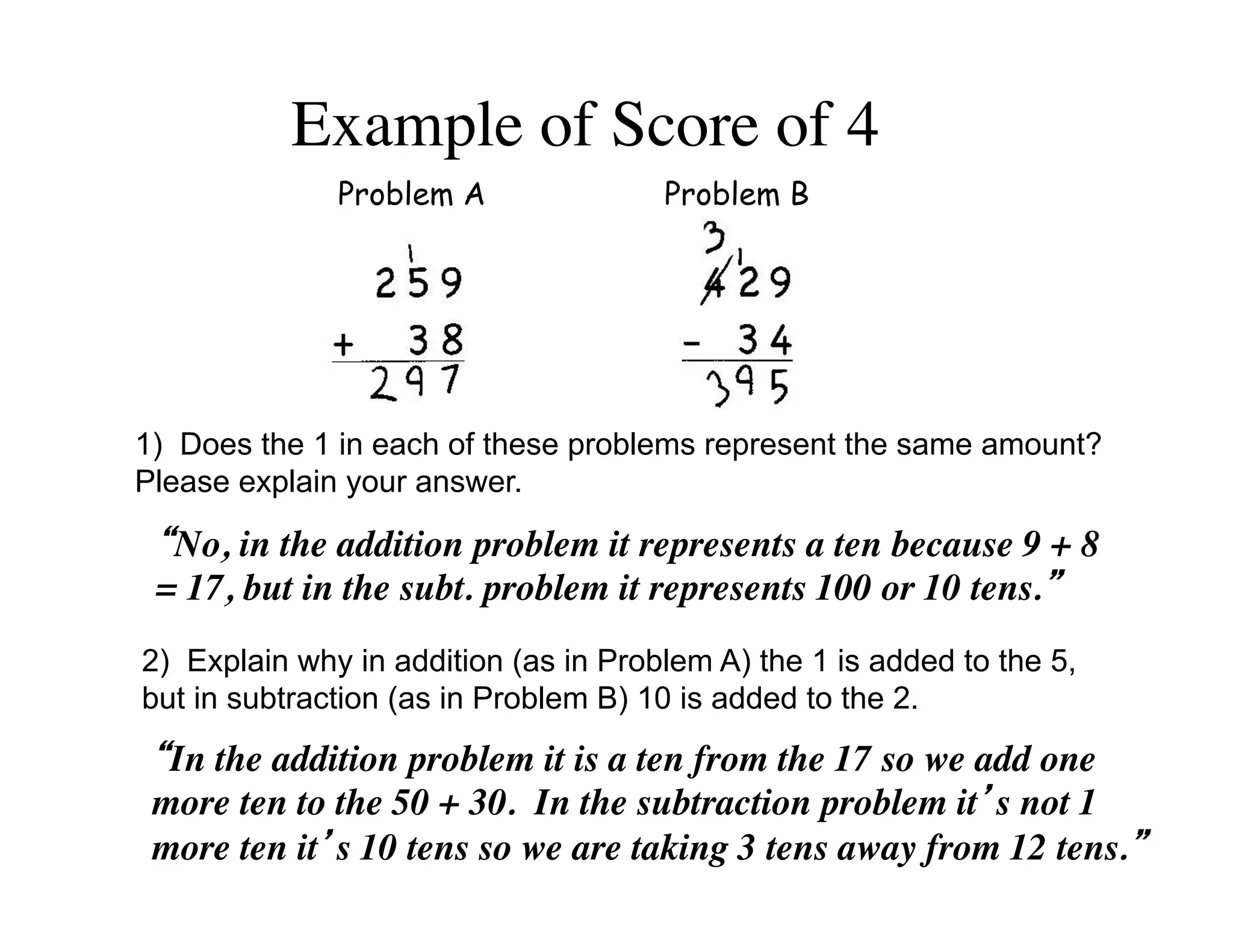

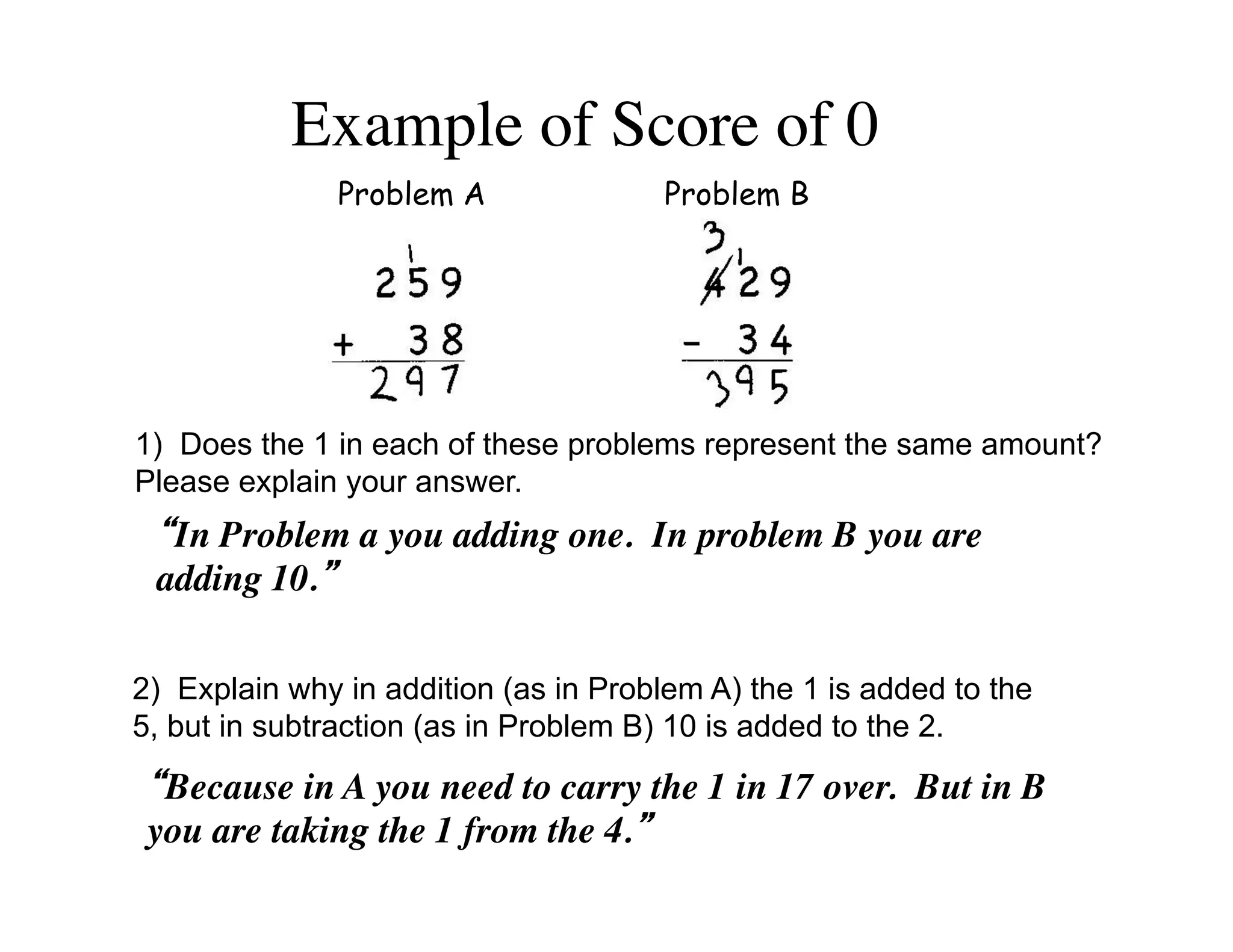

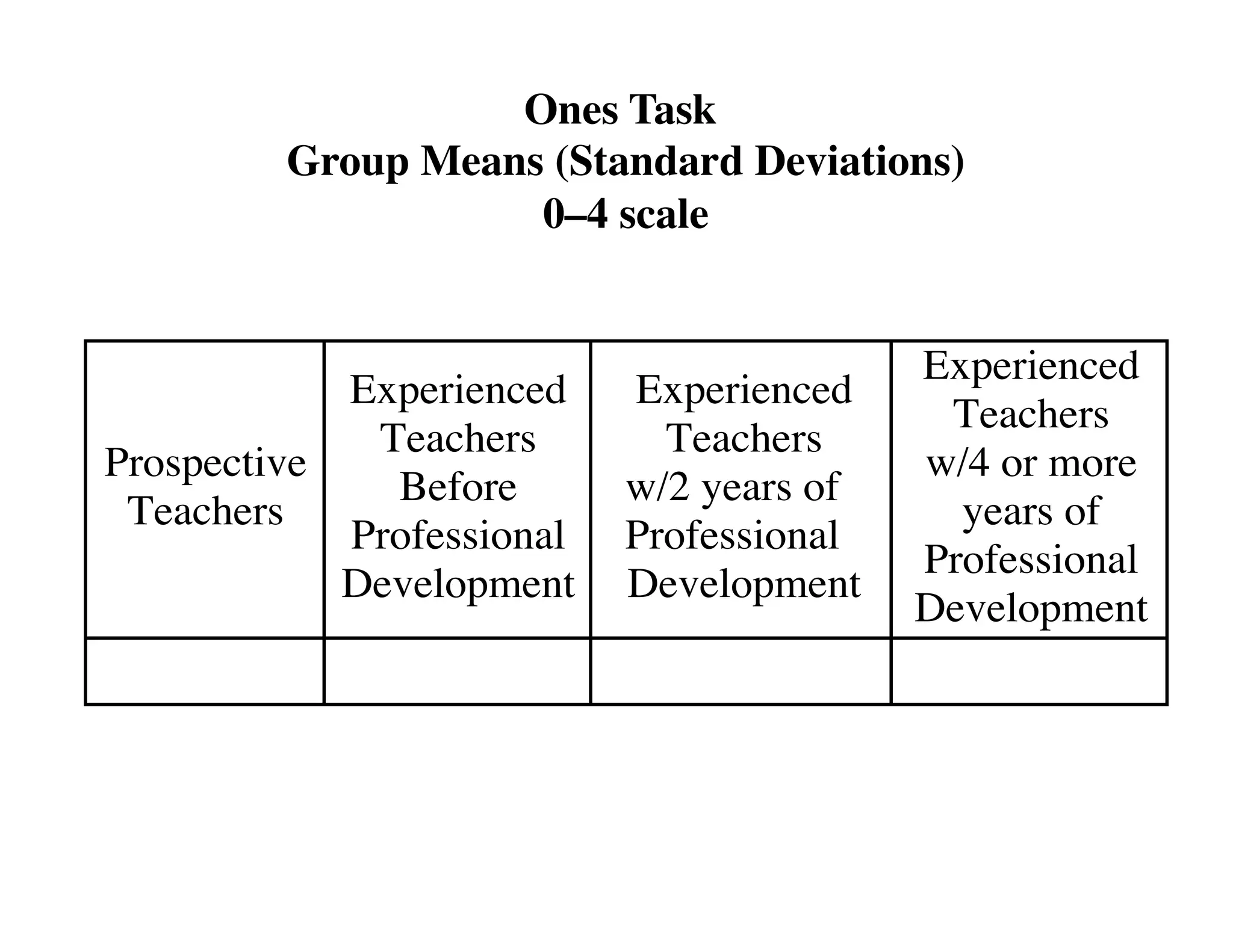

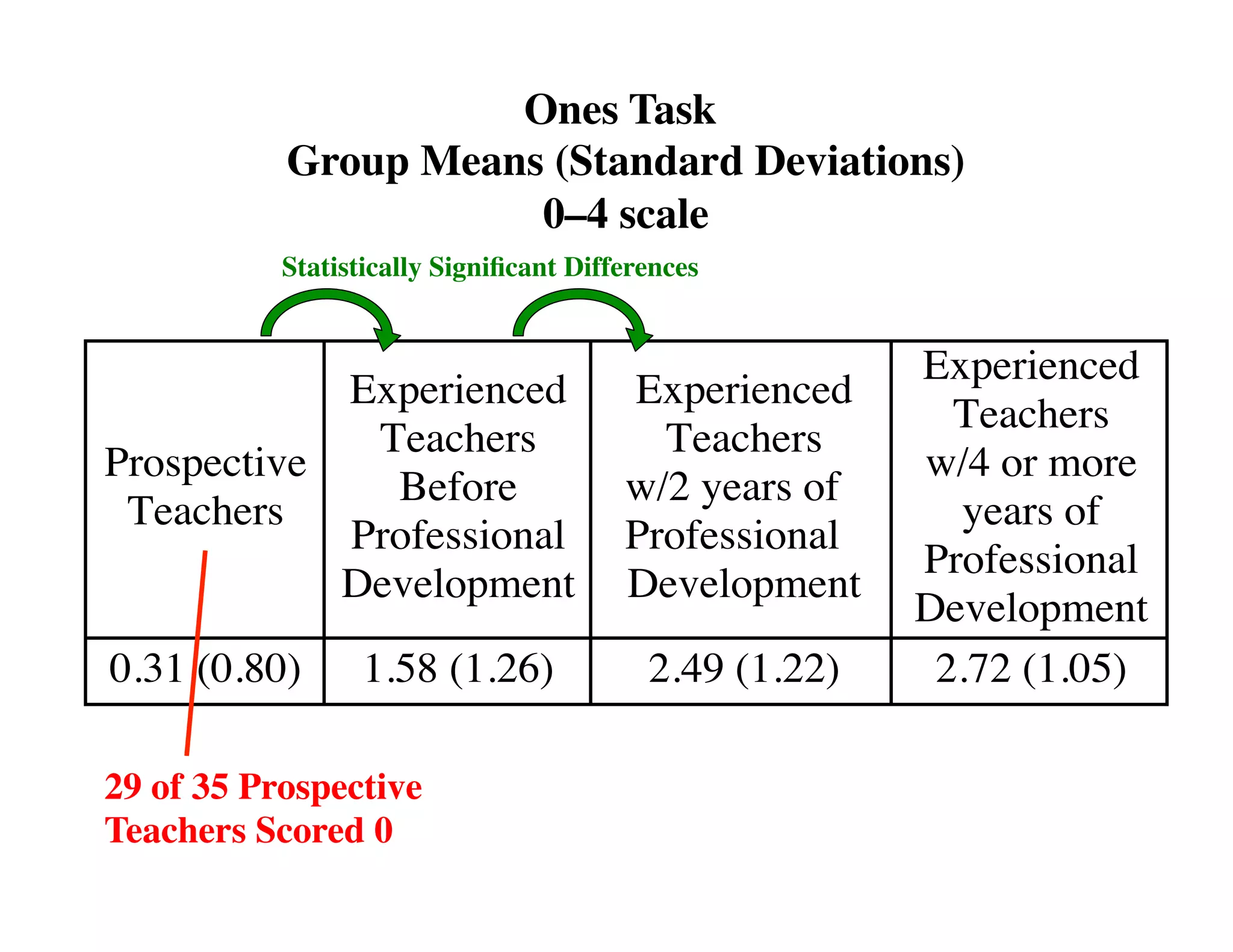

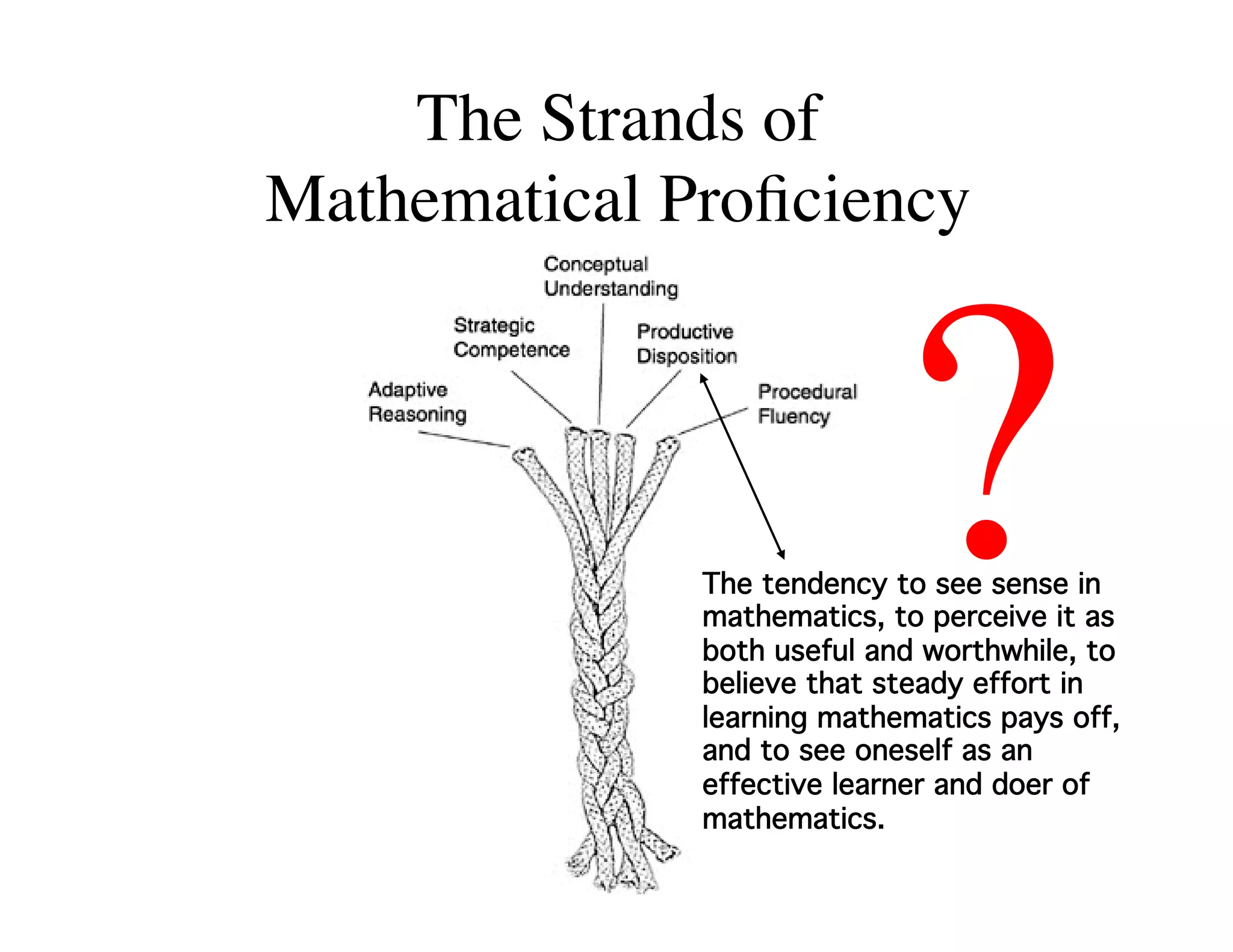

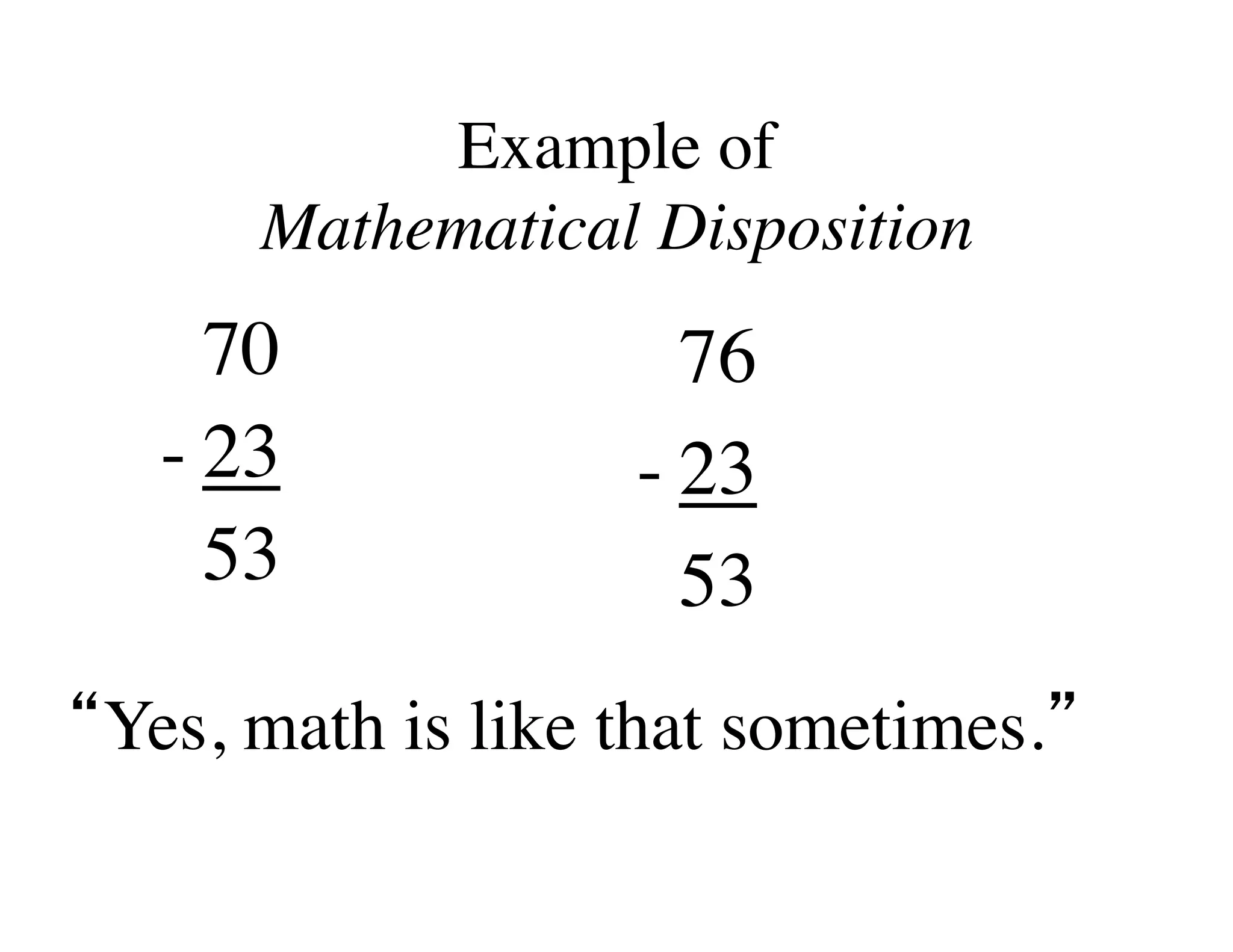

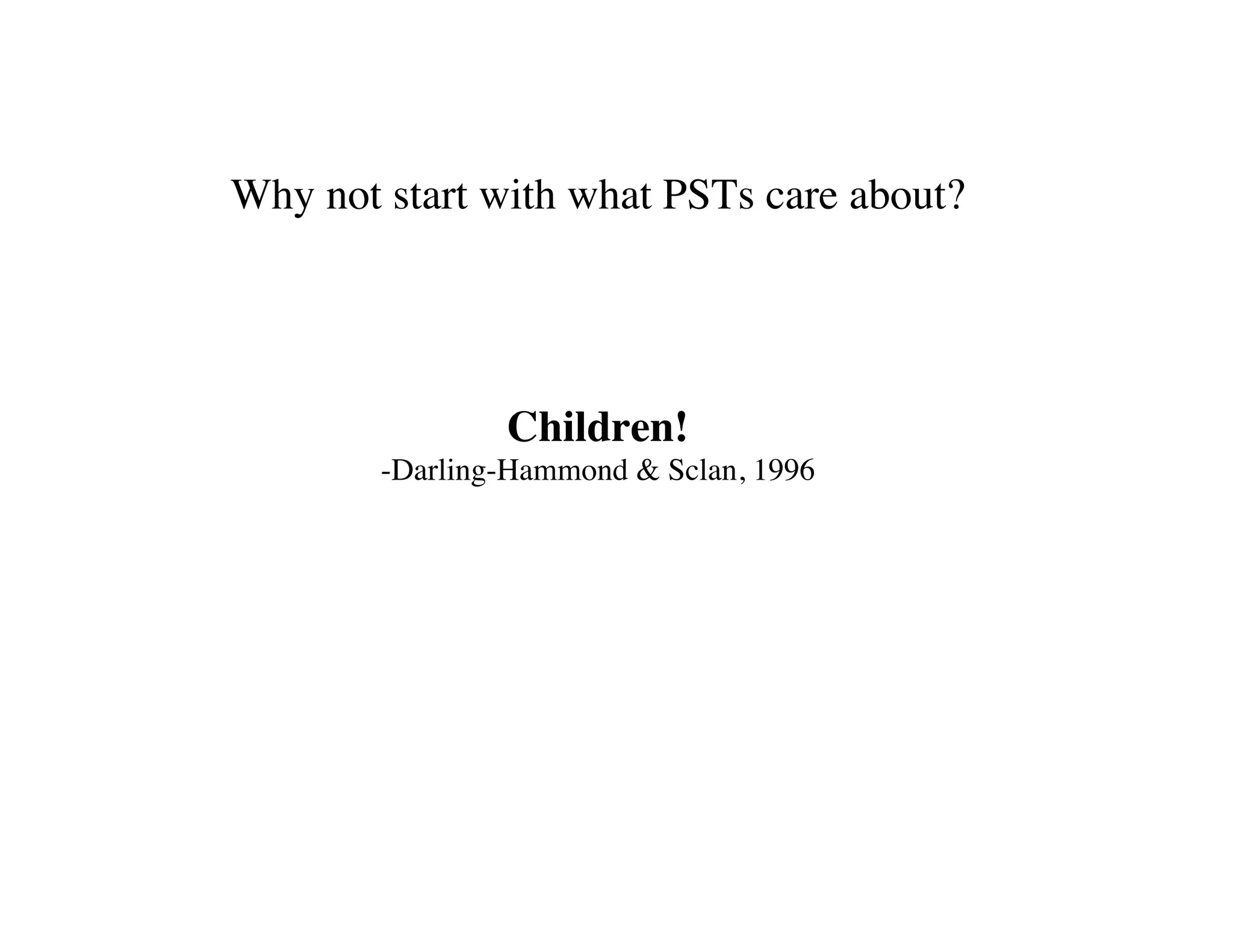

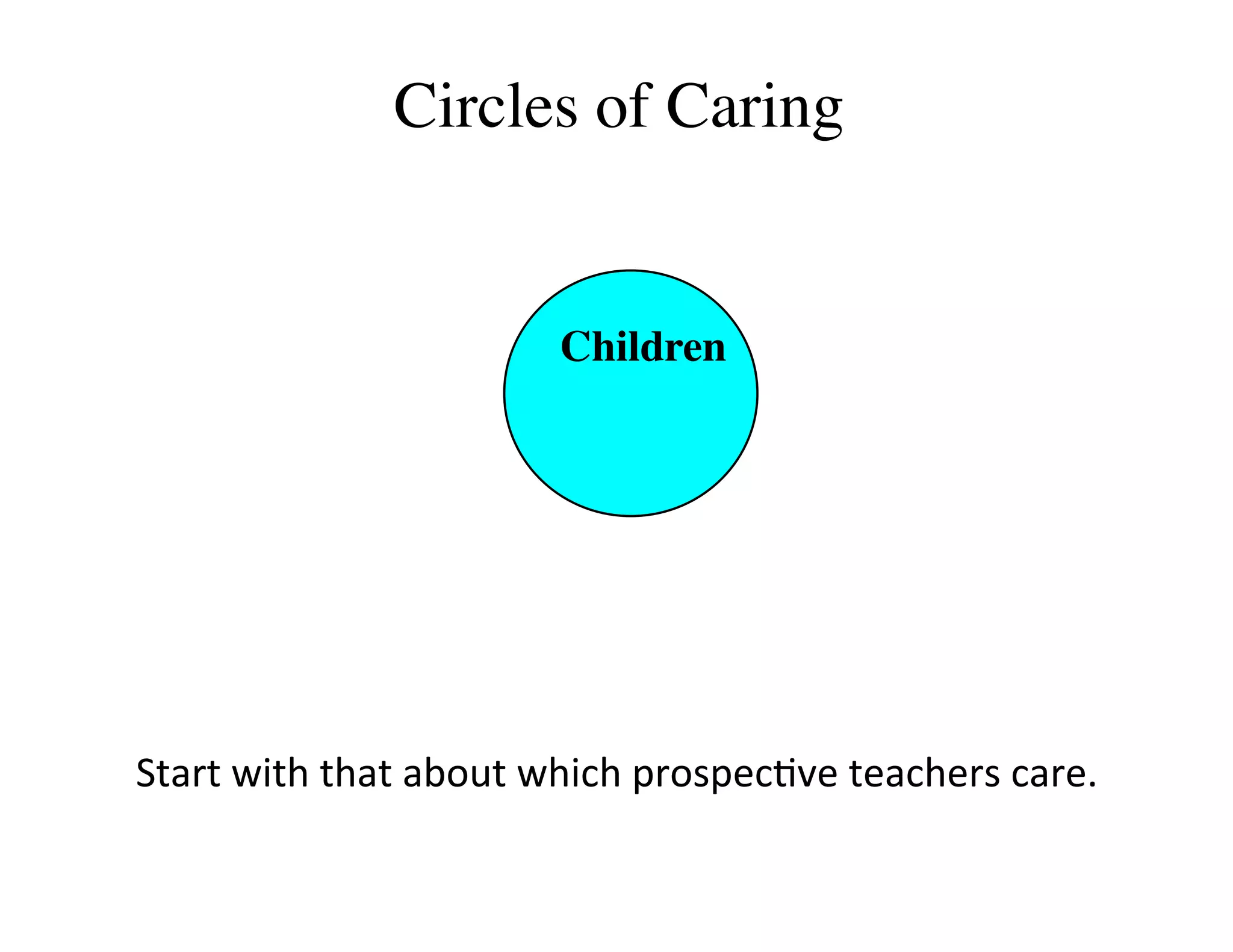

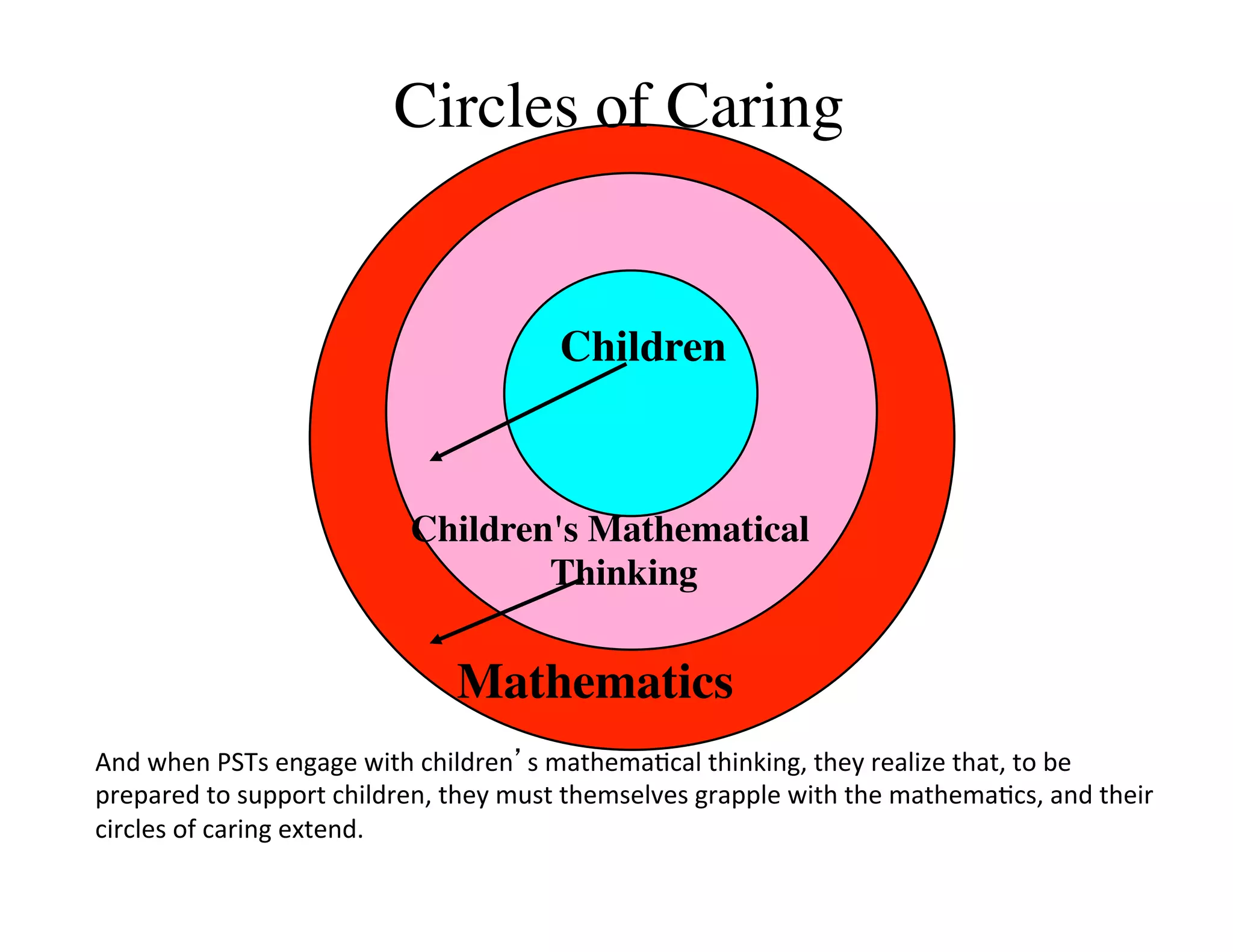

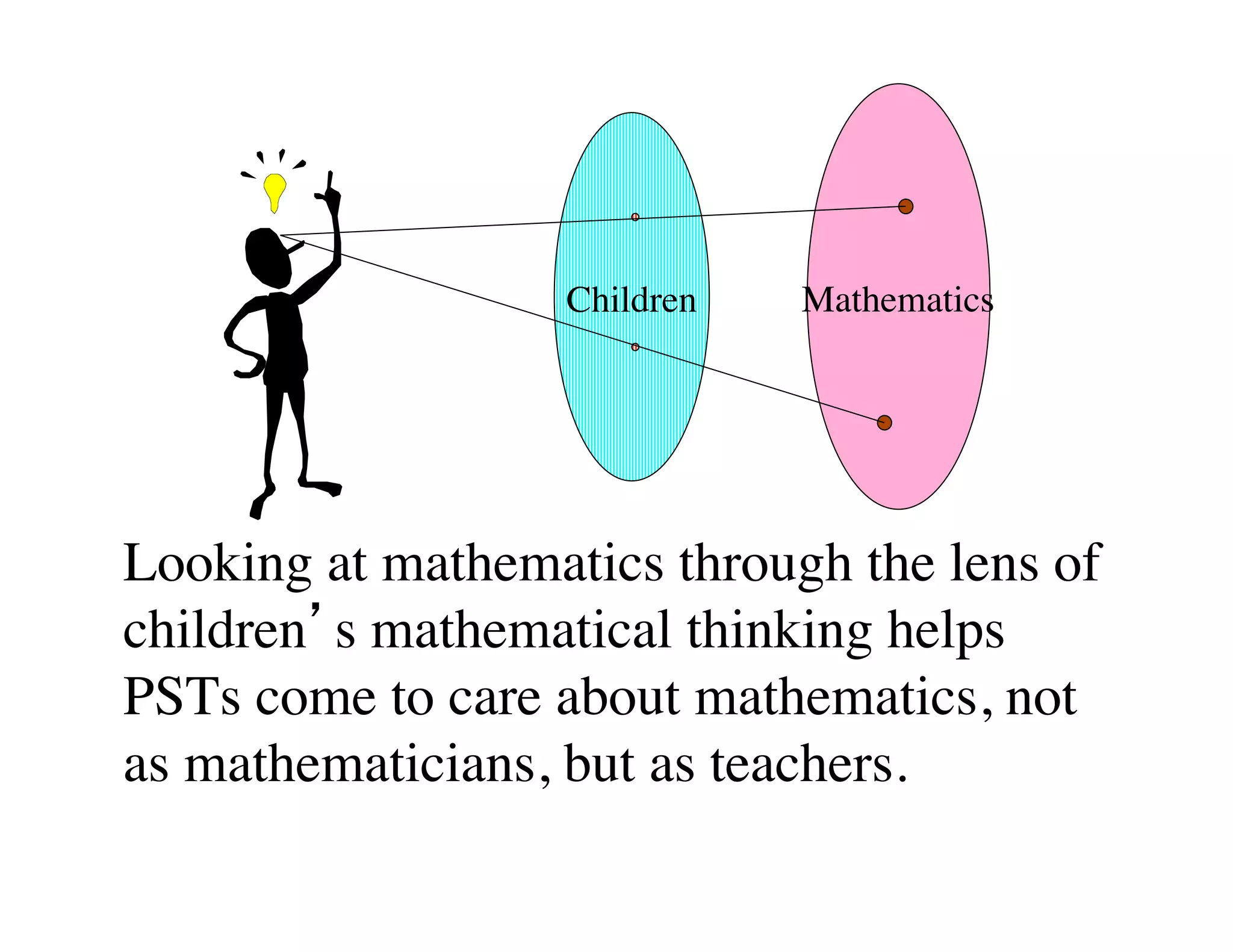

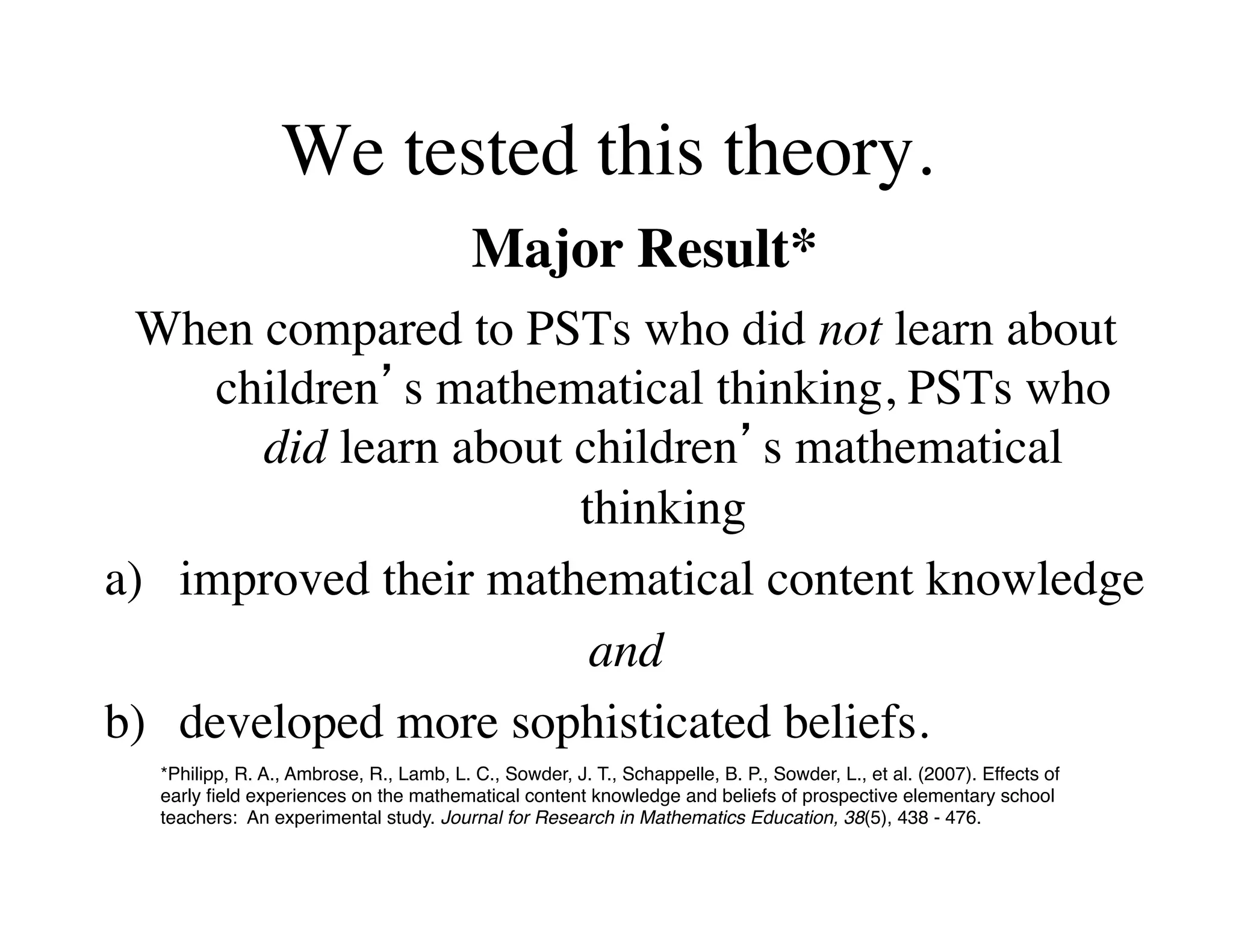

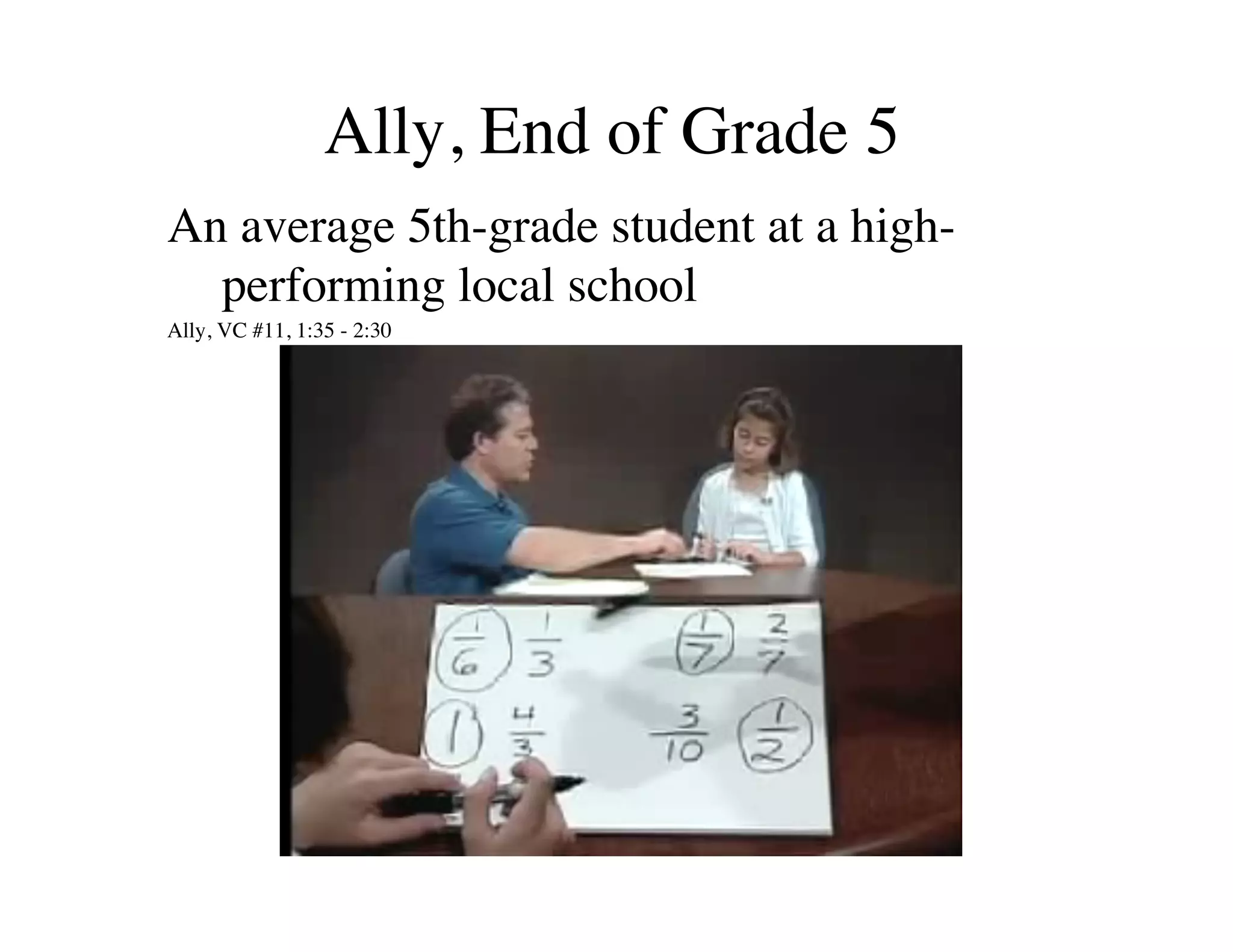

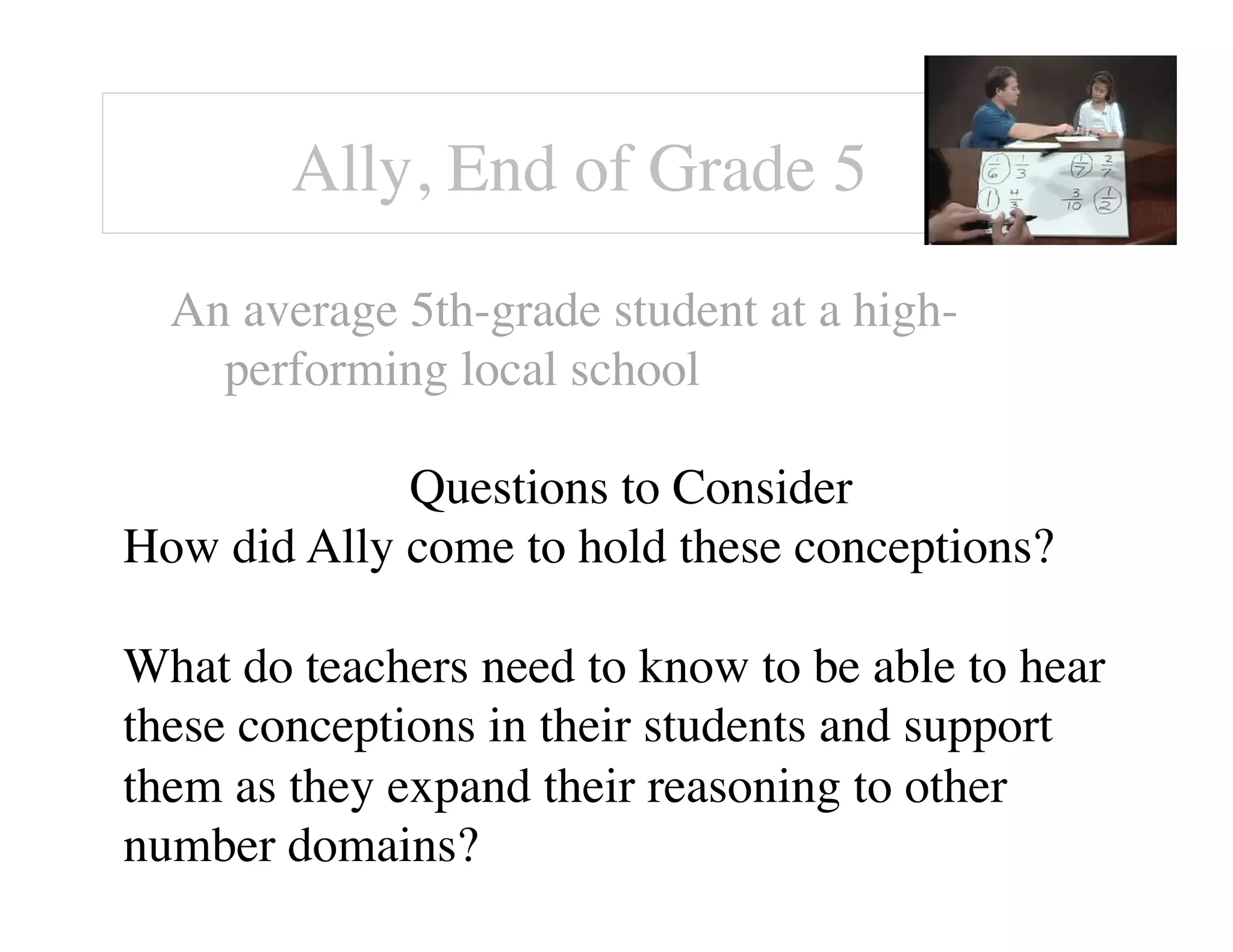

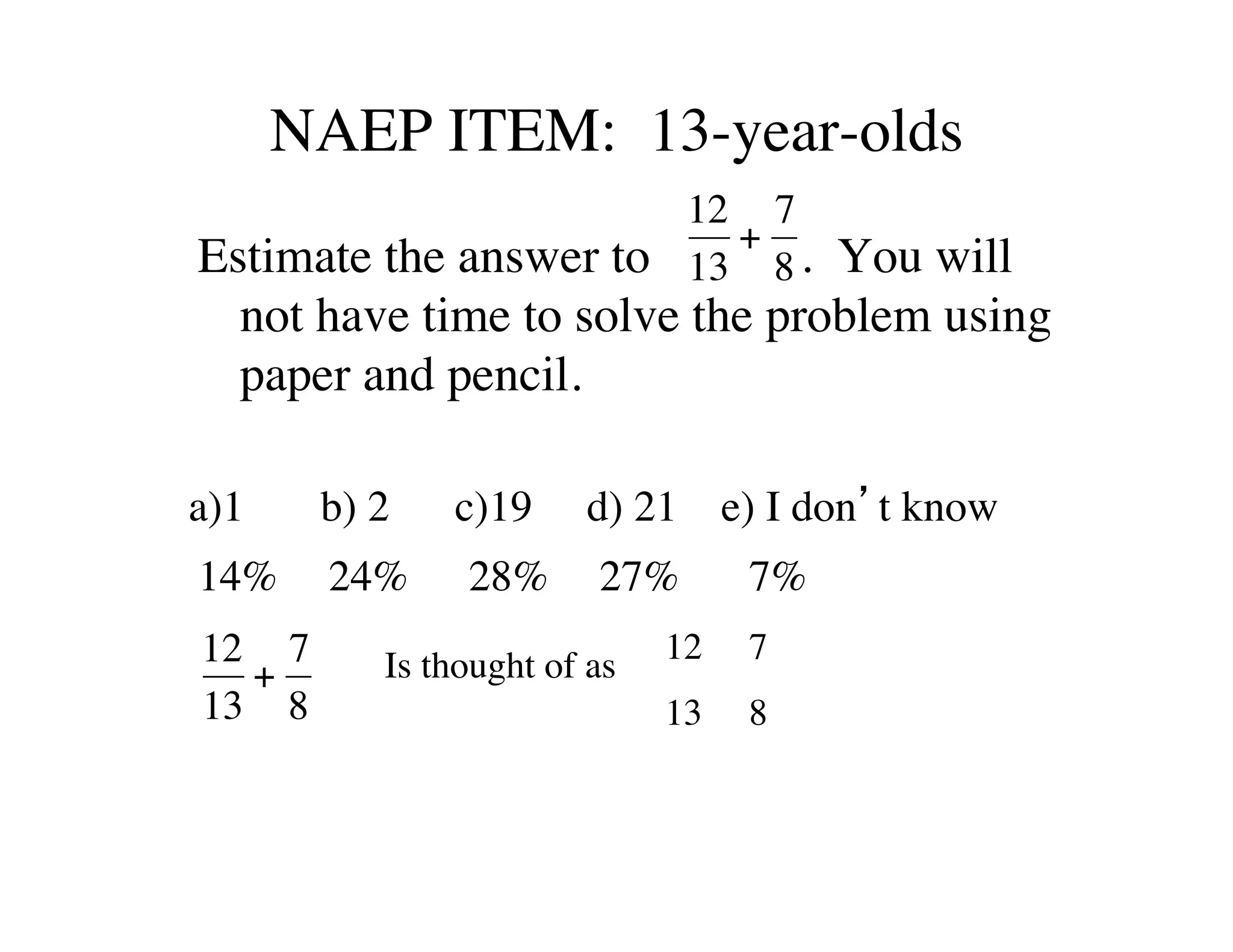

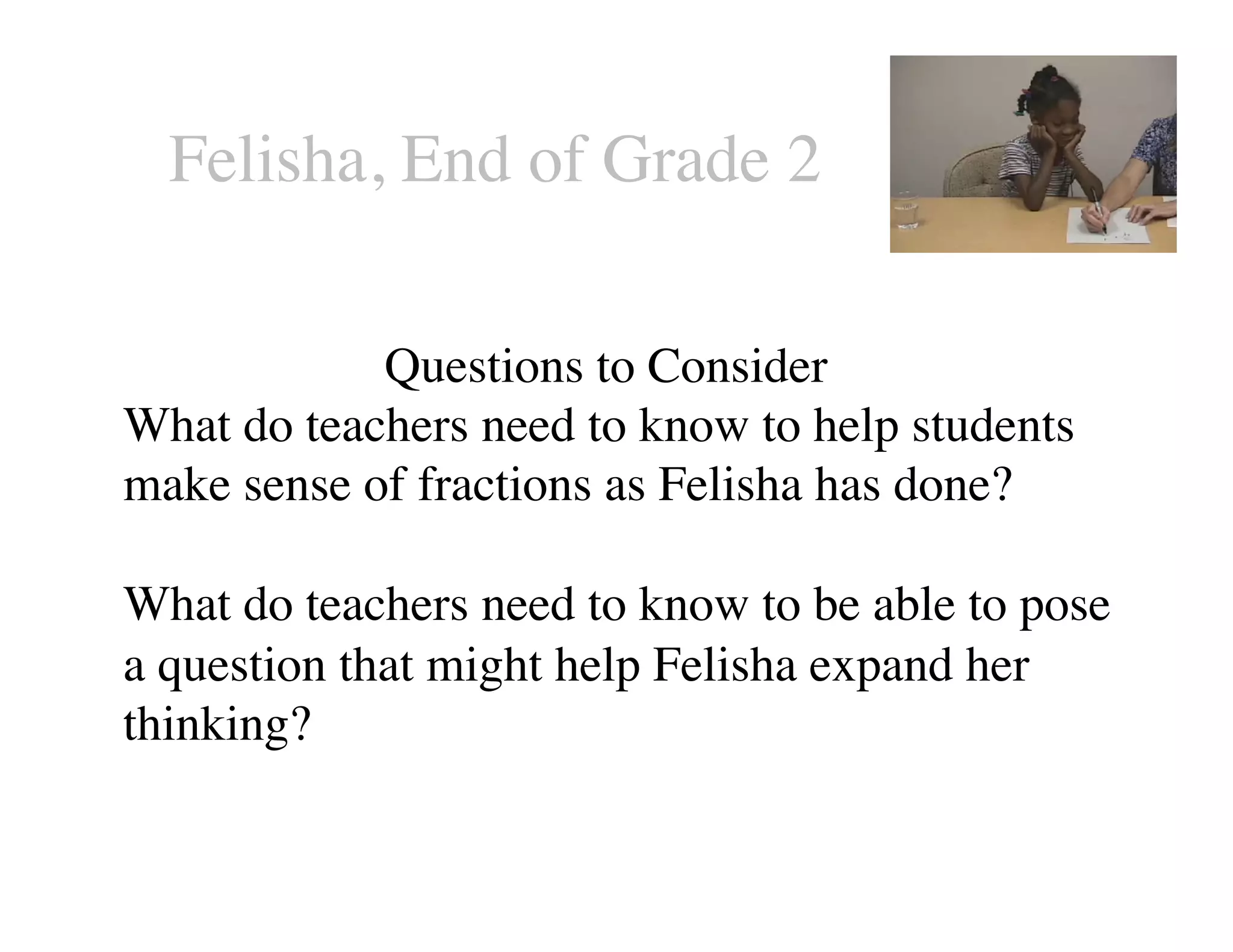

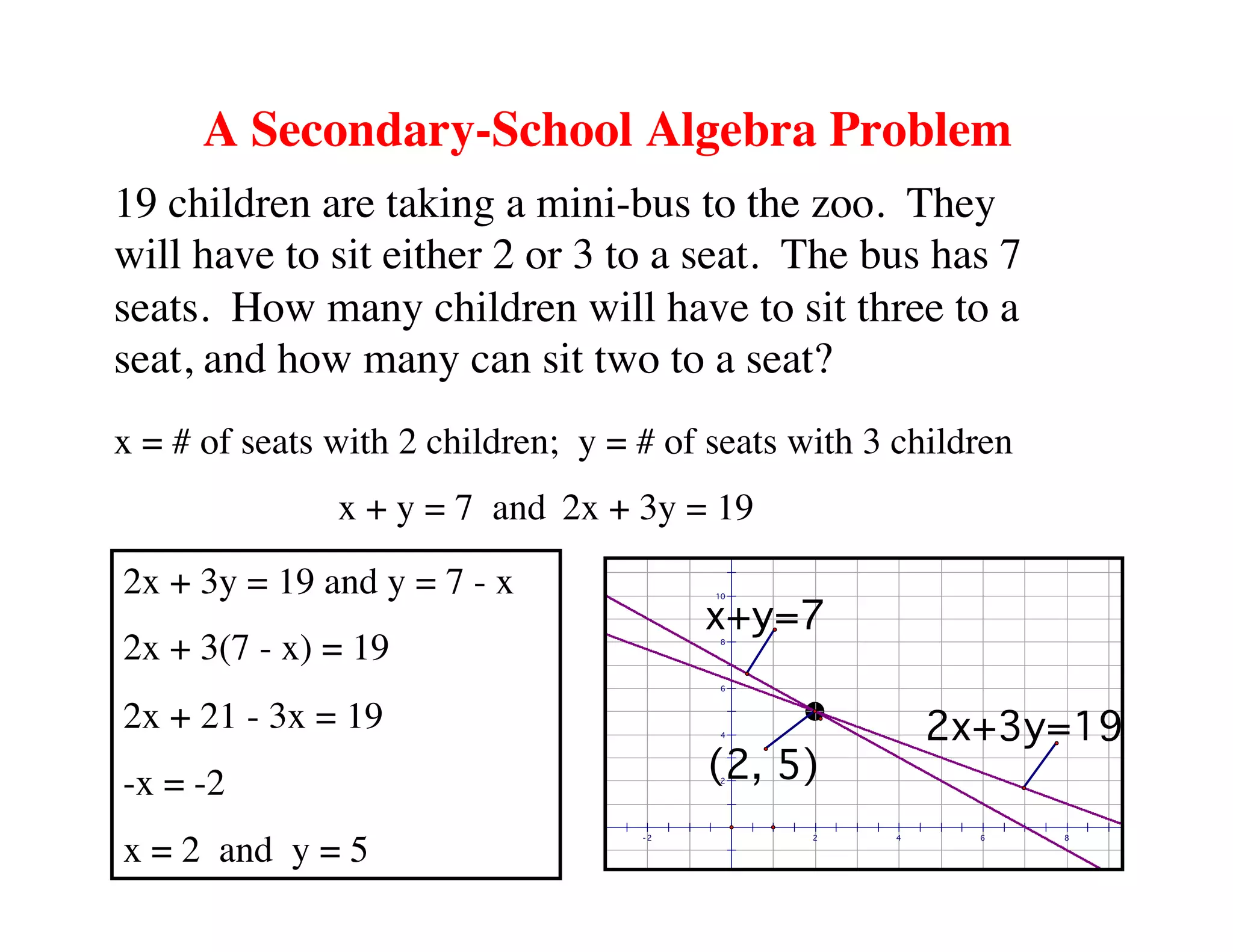

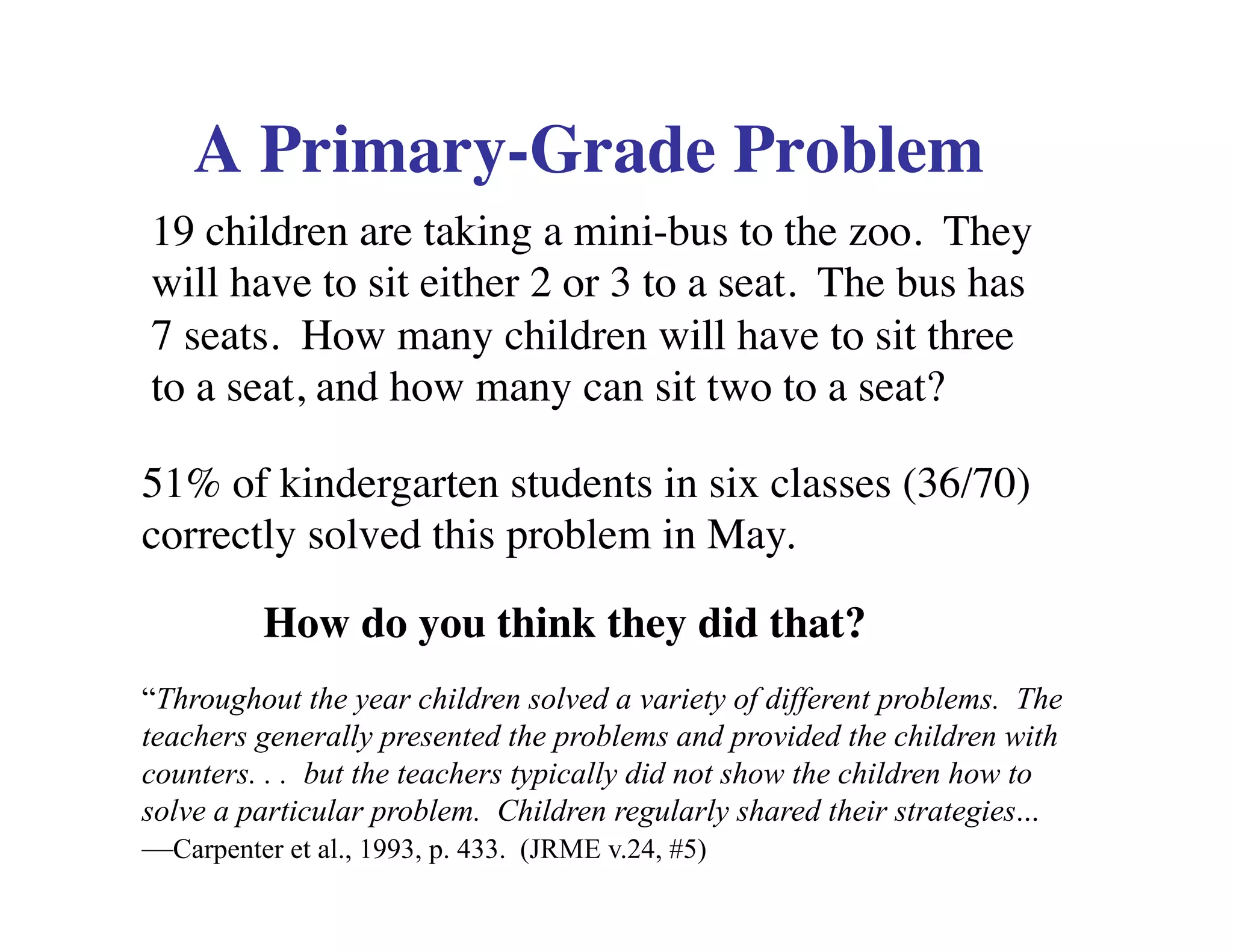

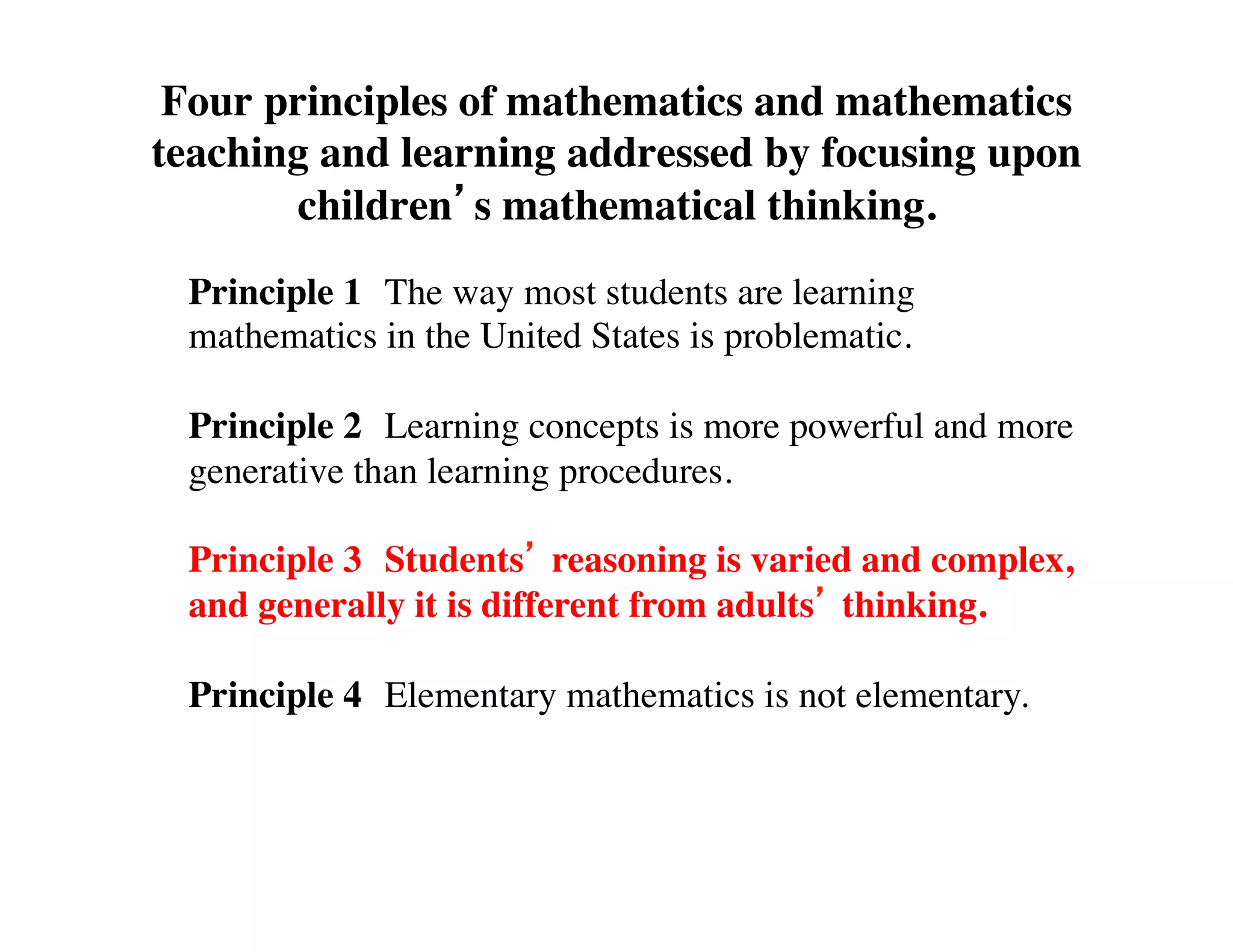

This document summarizes a presentation about preparing elementary school teachers to understand elementary mathematics. It discusses how elementary mathematics concepts can be complex and how focusing on children's mathematical thinking can help prospective teachers (PSTs) engage more deeply with mathematics. The presentation addresses four principles: 1) How students typically learn mathematics is problematic, 2) Learning concepts is more powerful than procedures, 3) Students' reasoning is varied and complex, and 4) Elementary math is not as elementary as assumed. Research found PSTs who learned about children's thinking improved their math knowledge and developed more sophisticated beliefs than those who did not.

![This

idea

is

at

least

100

years

old.

John Dewey, 1902

Every

subject

has

two

aspects,

“one

for

the

scien=st

as

a

scien=st;

the

other

for

the

teacher

as

a

teacher”

(p.

351).

“[The

teacher]

is

concerned,

not

with

the

subject-‐maFer

as

such,

but

with

the

subject-‐maFer

as

a

related

factor

in

a

total

and

growing

experience

[of

the

child]”

(p.

352).

!

!

Dewey, J. (1902/1990). The child and the curriculum.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. !](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/qwc5hktcgvdpwp1guzyw-signature-ad95e2248ce0b328f93e90463efa1e299db3423ce6a37df2f25301dada4a2fc7-poli-140924075046-phpapp01/75/Philipp-pm-slides-39-2048.jpg)

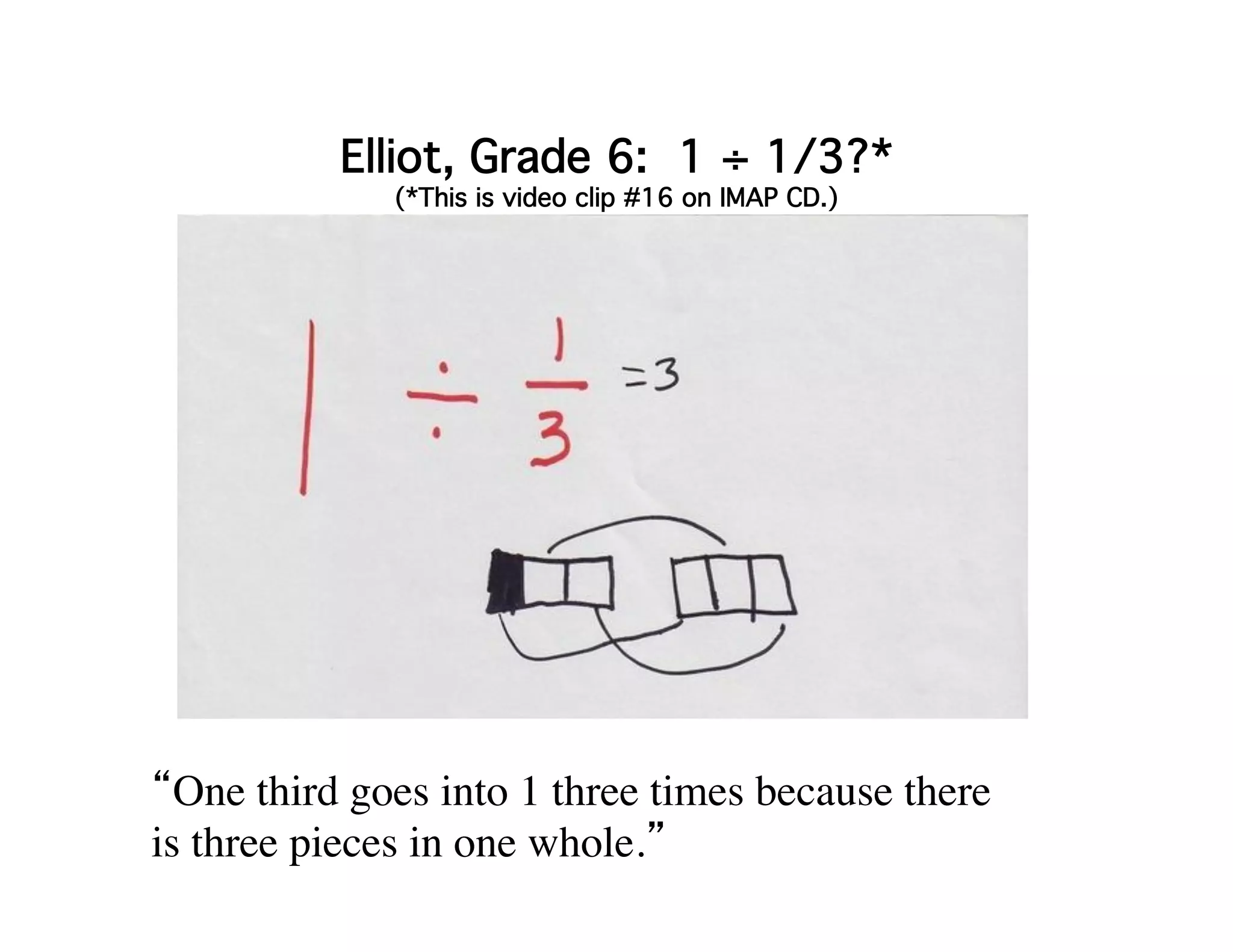

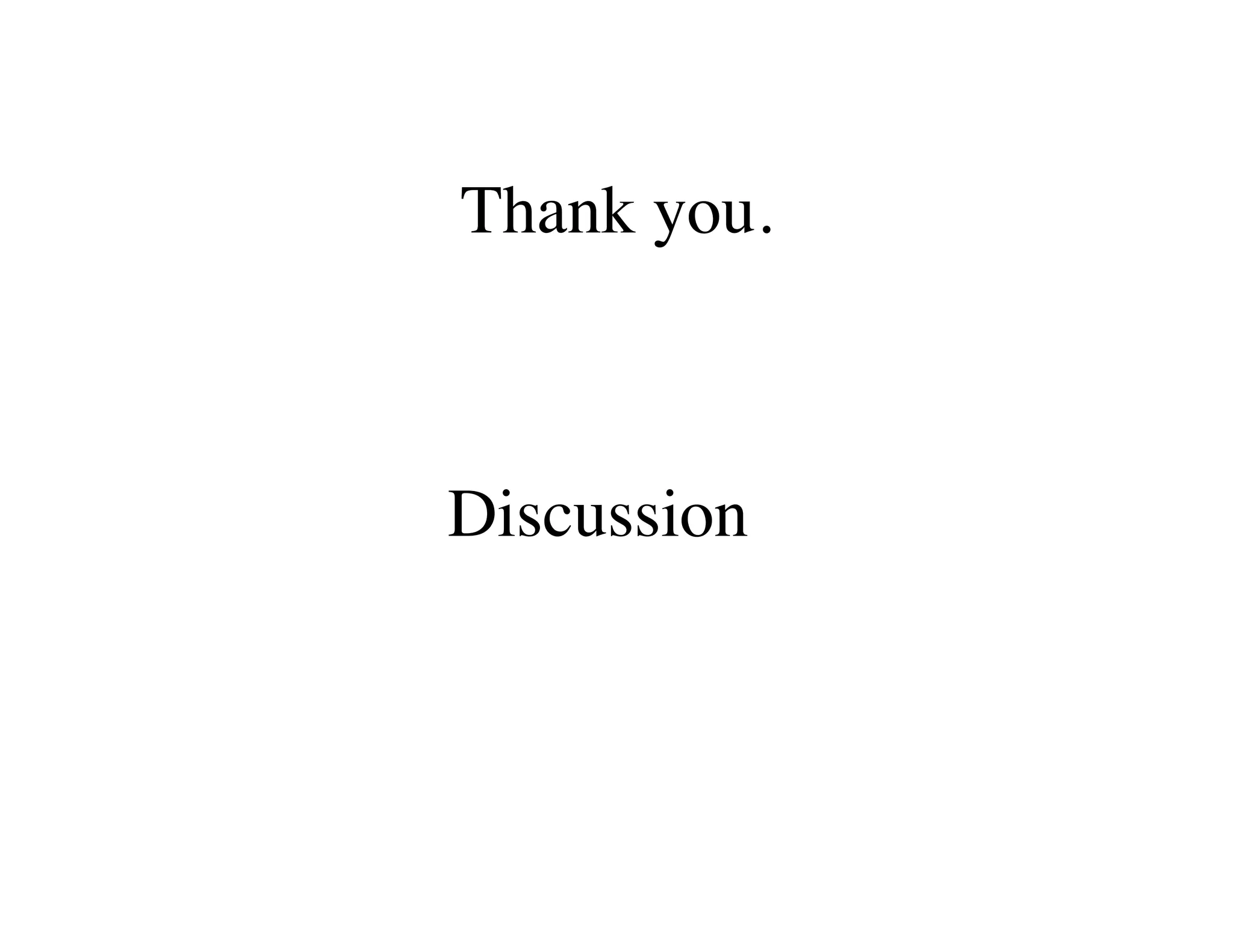

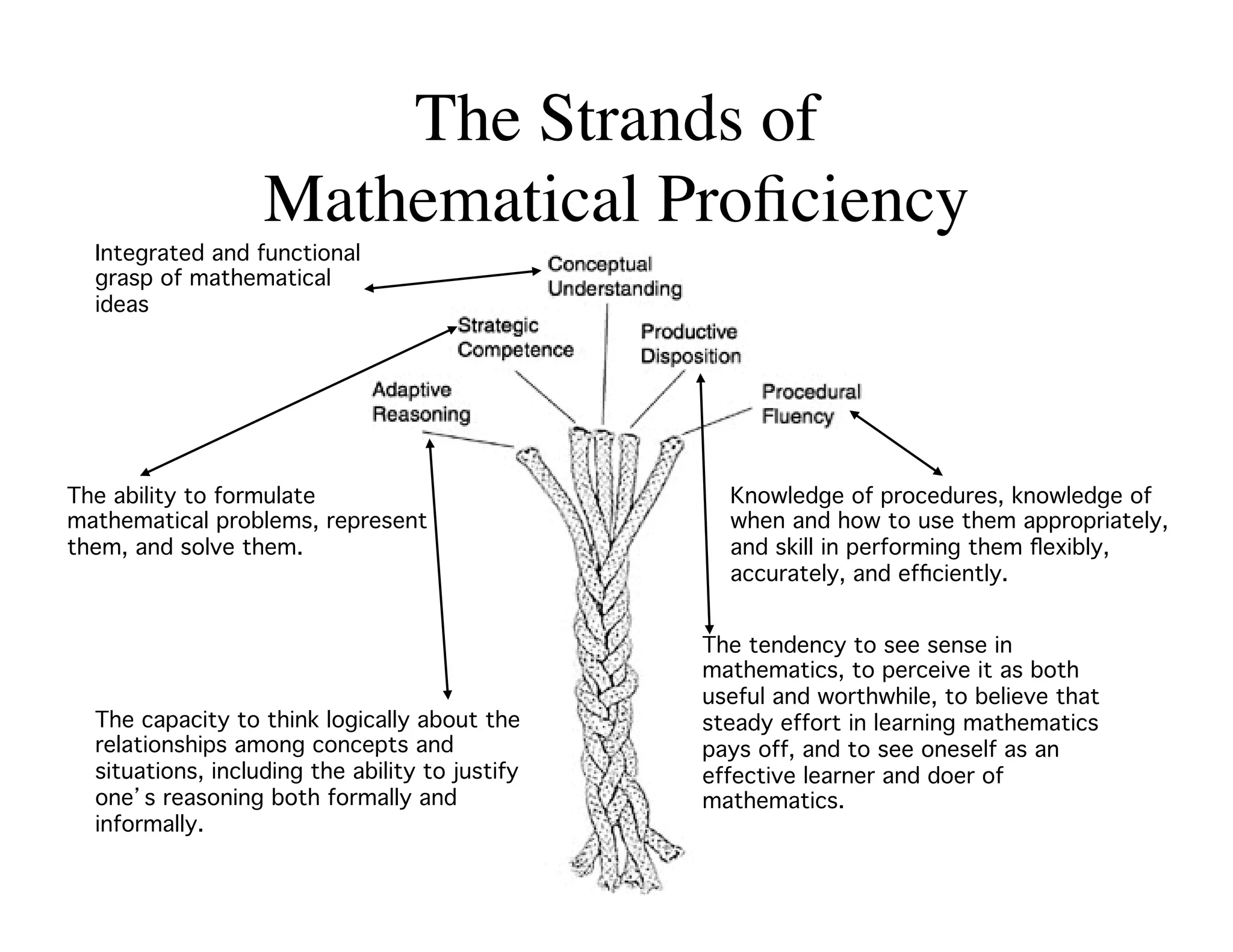

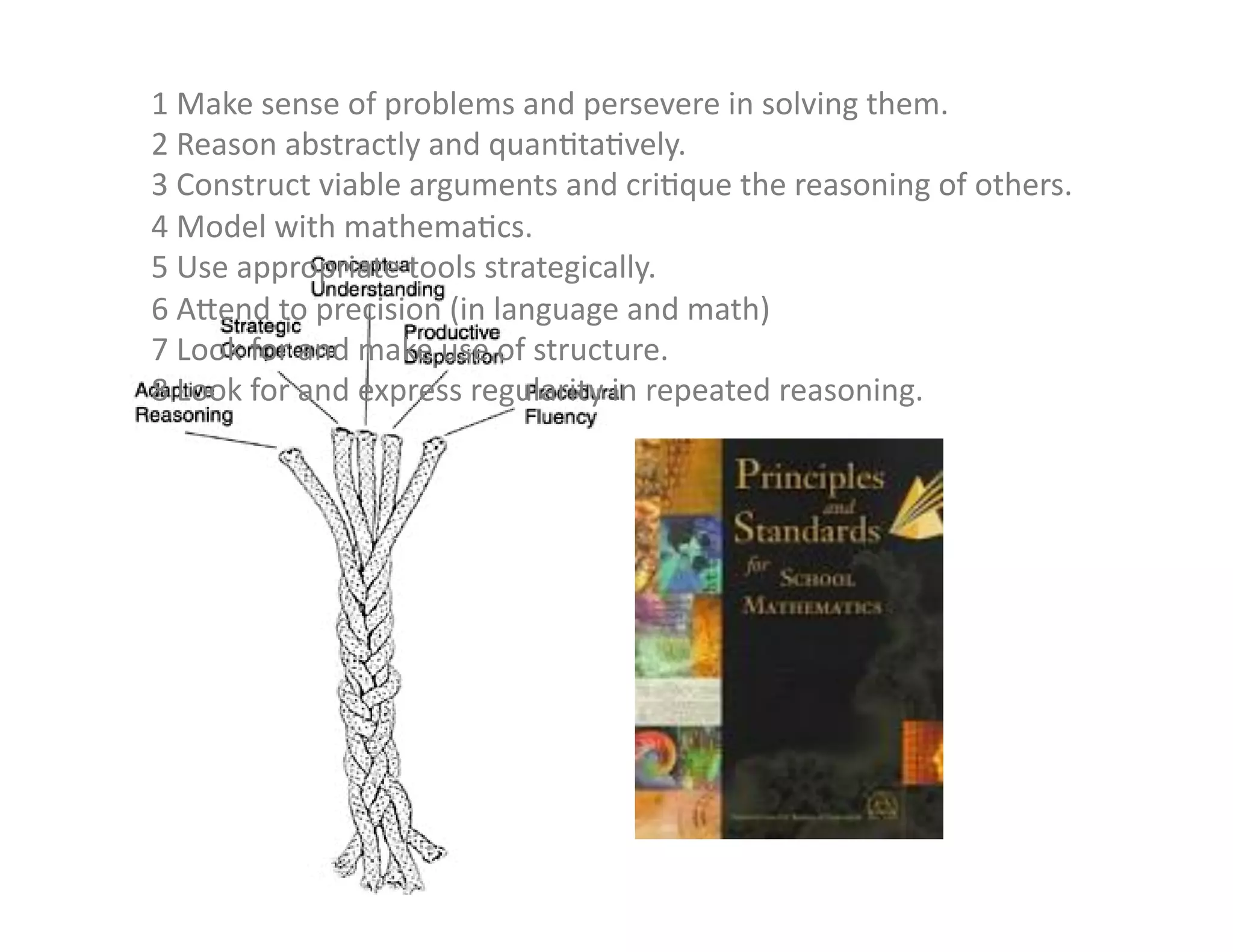

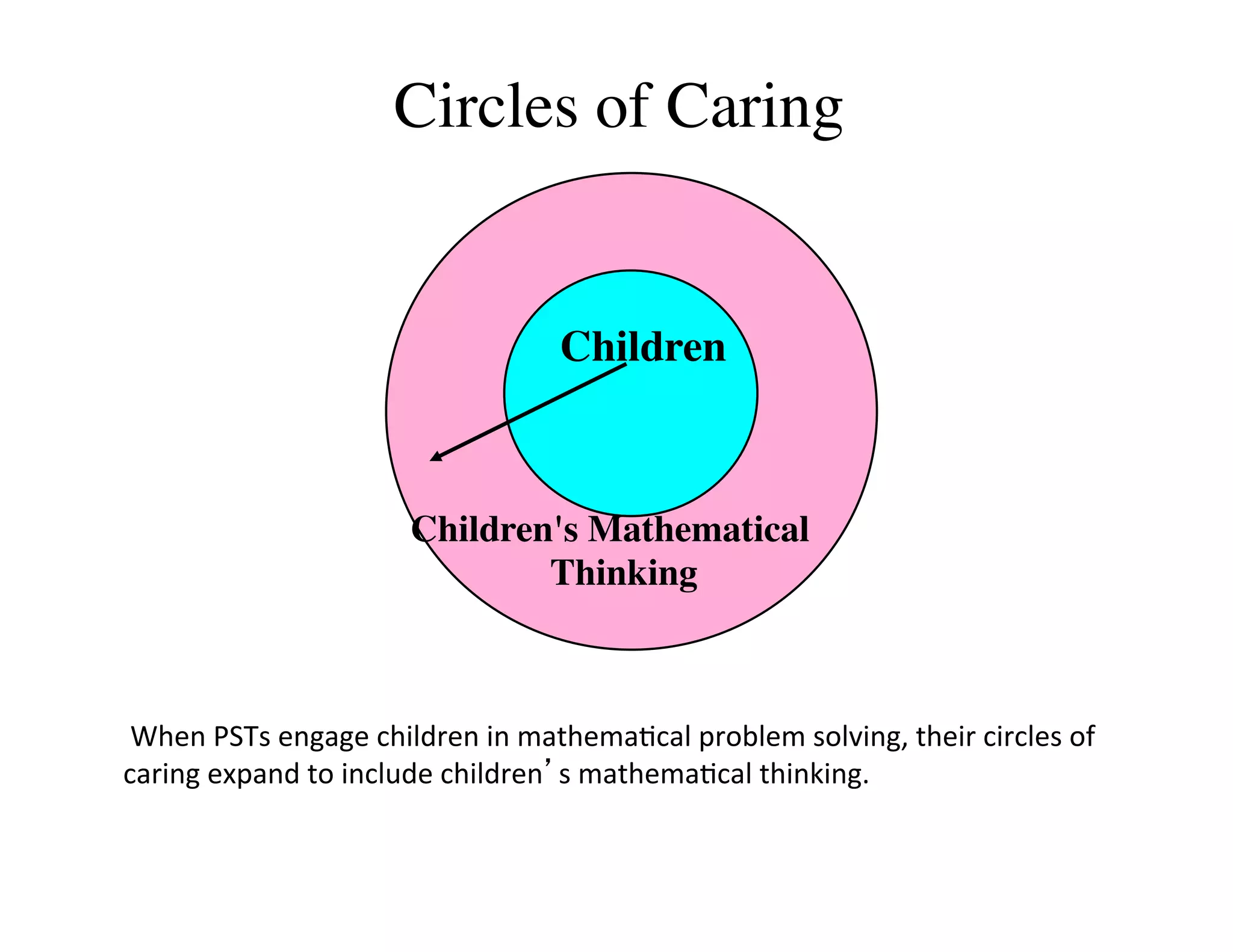

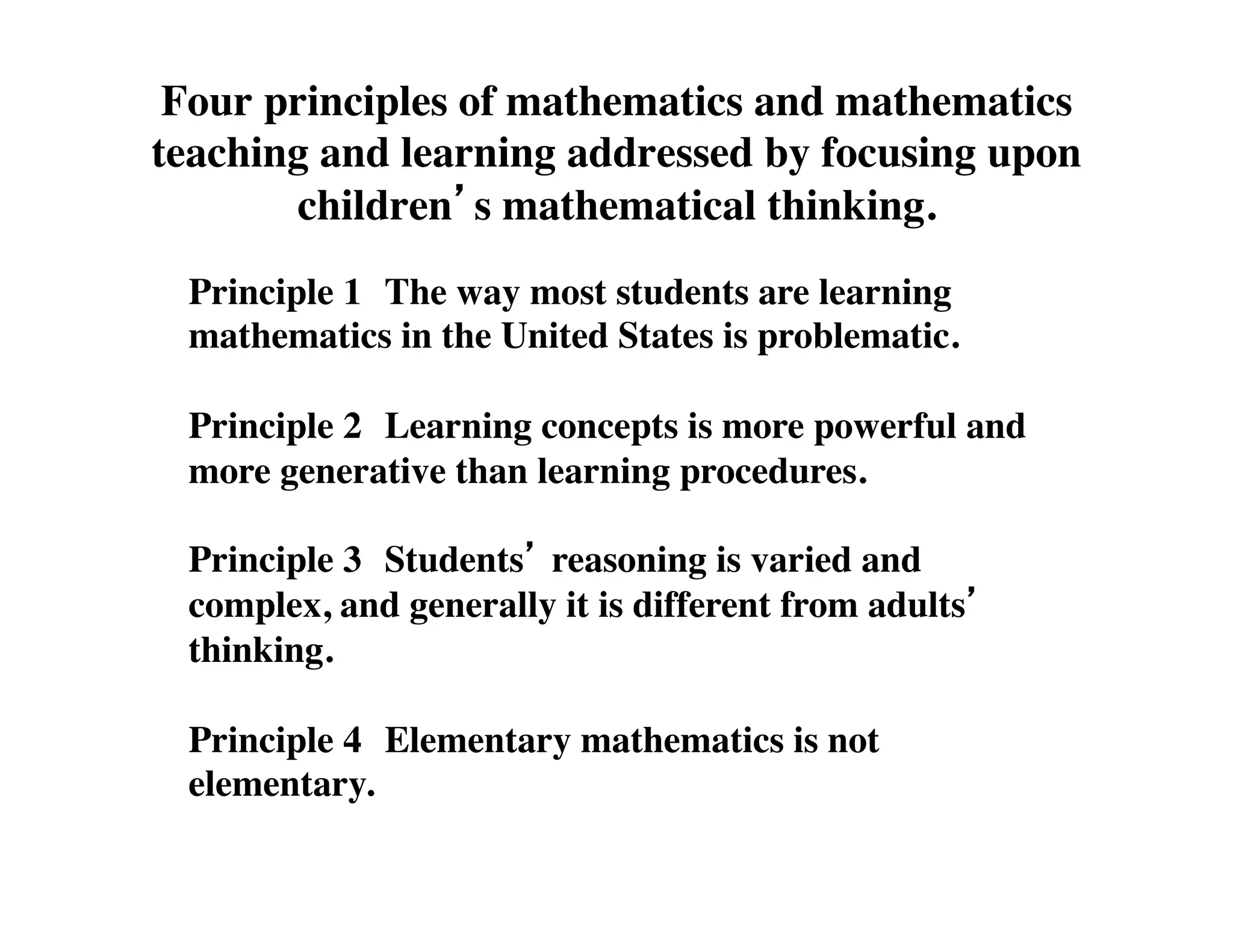

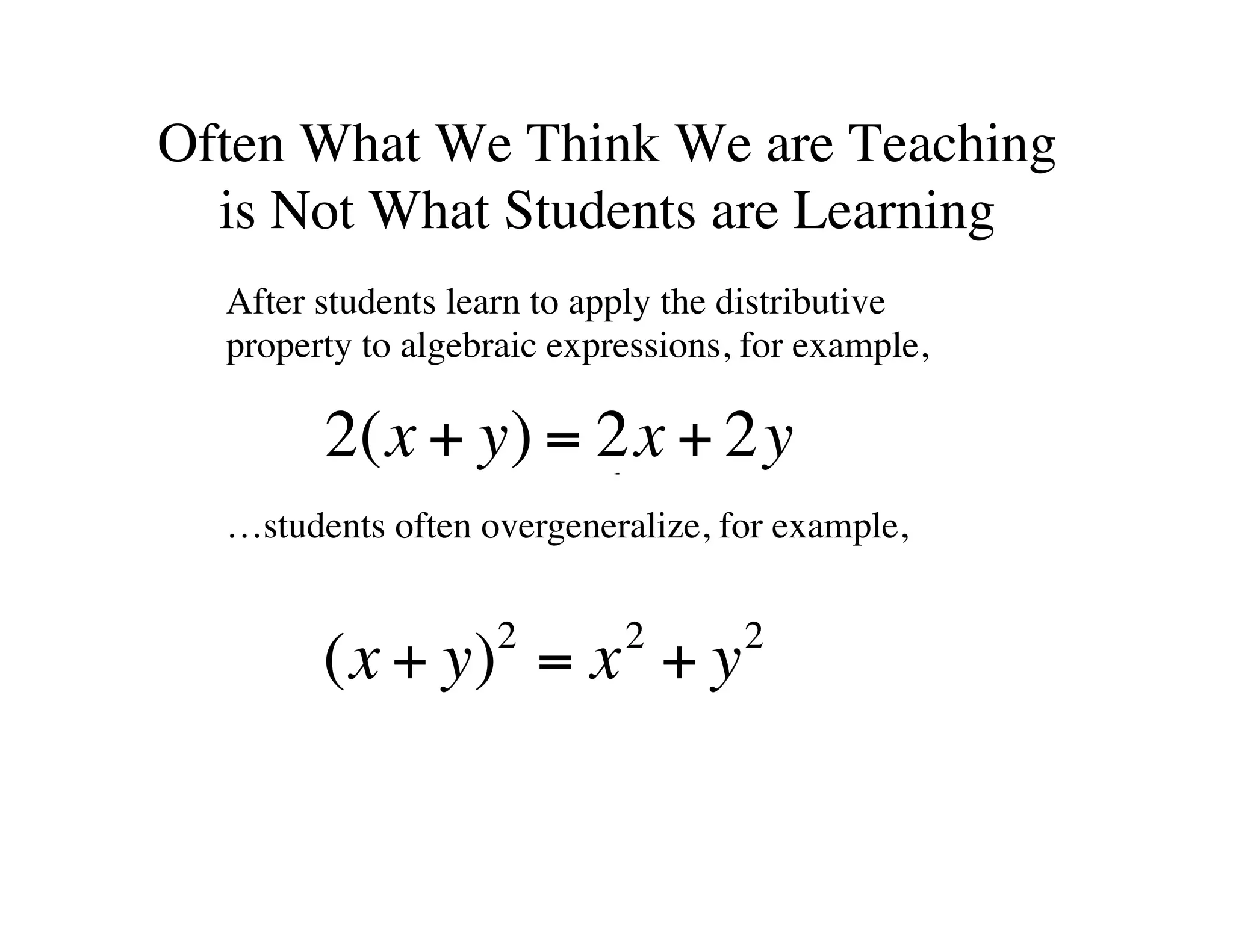

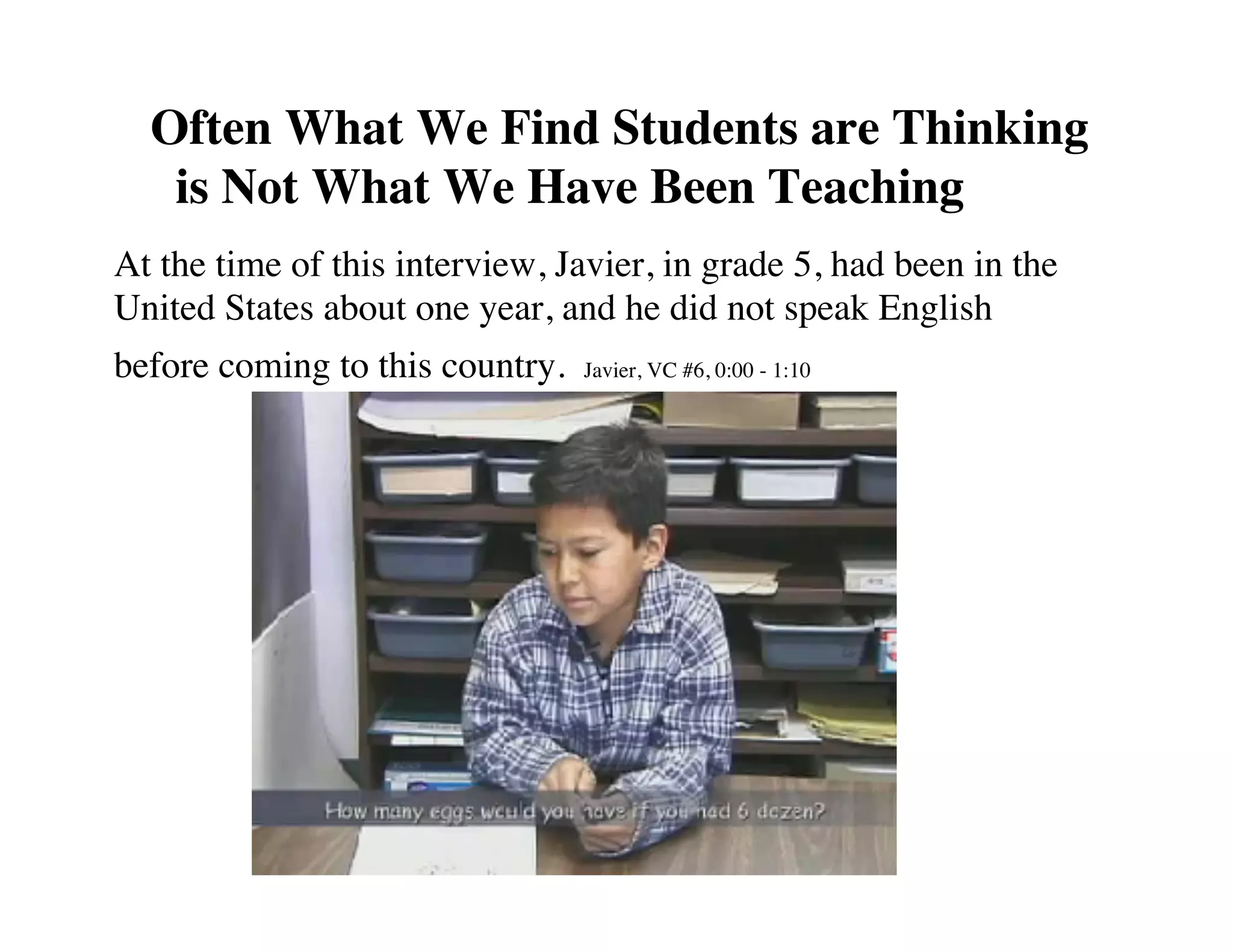

![Javier*, Grade 5

How many eggs are in six cartons (of one dozen)?

Javier thinks for 15 seconds, and says, “72.”

I: How did you get that?

Javier writes and says, “5 times 12 is 60, and 12

more is 72.”

I: “How did you know 12 x 5 is 60?”

J: “Because 12 times 10 equals 120. If I take

the [sic] half of 120, that would be 60.”

*At the time of this interview, Javier had been in the United States about one year, and

he did not speak English before coming to this country.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/qwc5hktcgvdpwp1guzyw-signature-ad95e2248ce0b328f93e90463efa1e299db3423ce6a37df2f25301dada4a2fc7-poli-140924075046-phpapp01/75/Philipp-pm-slides-61-2048.jpg)

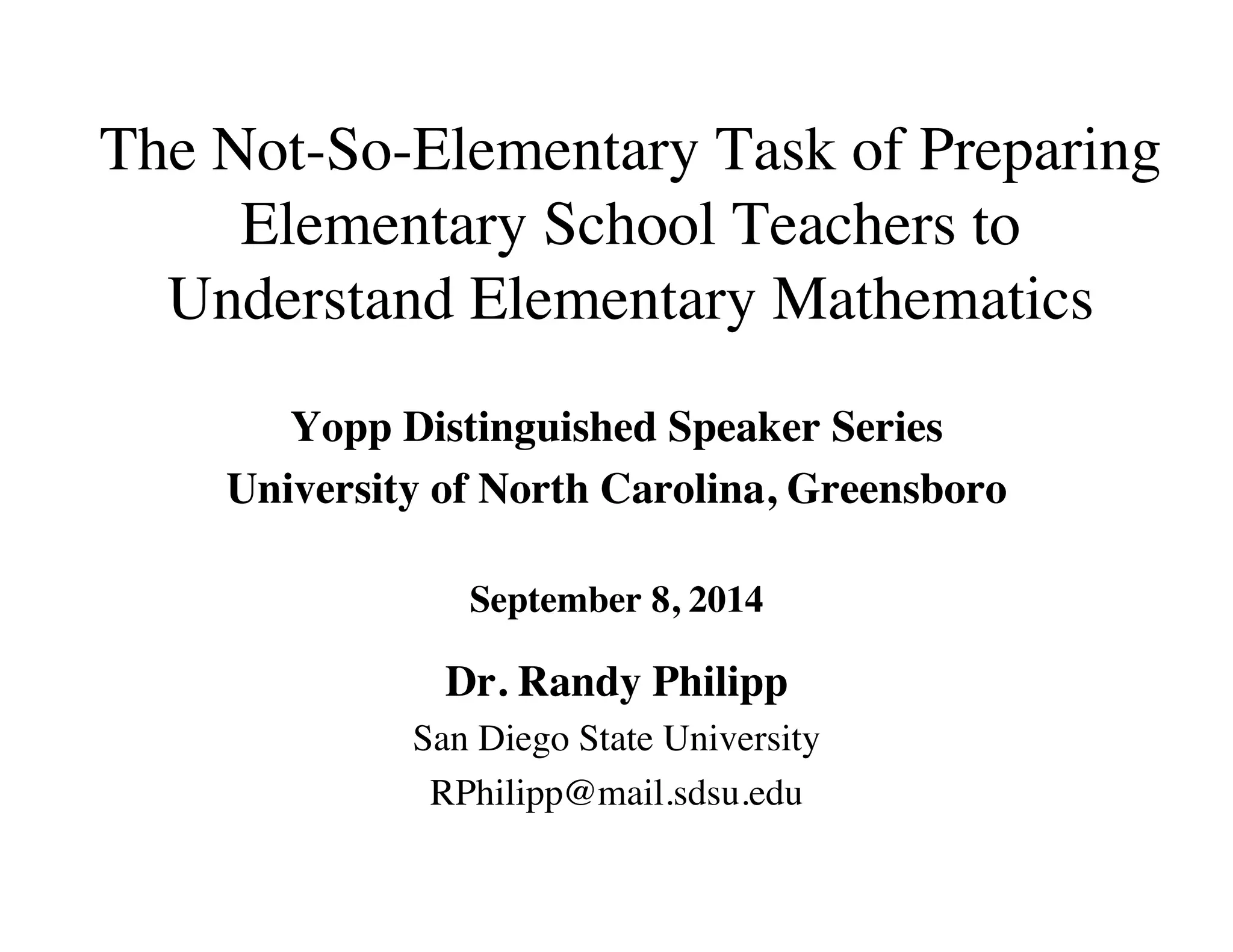

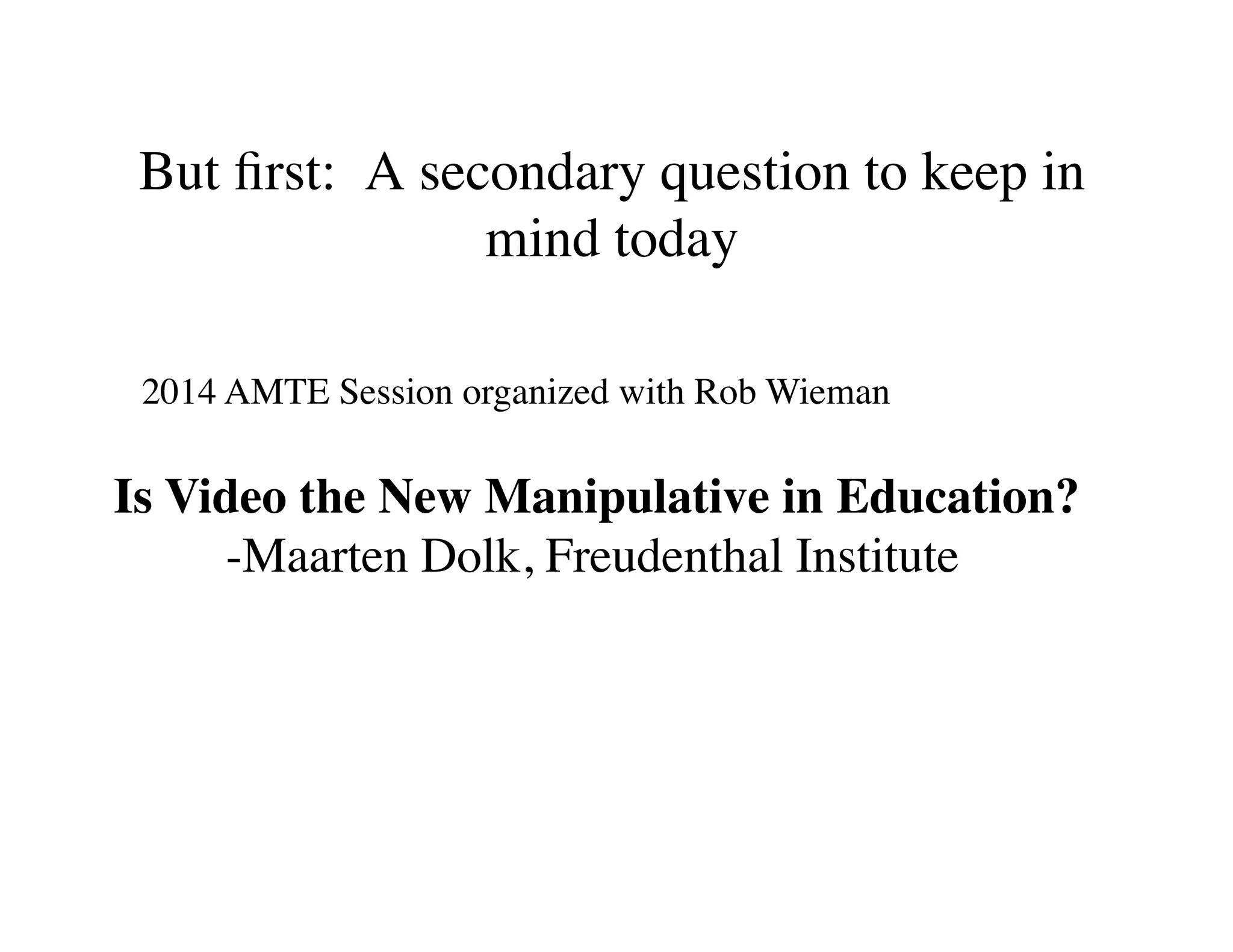

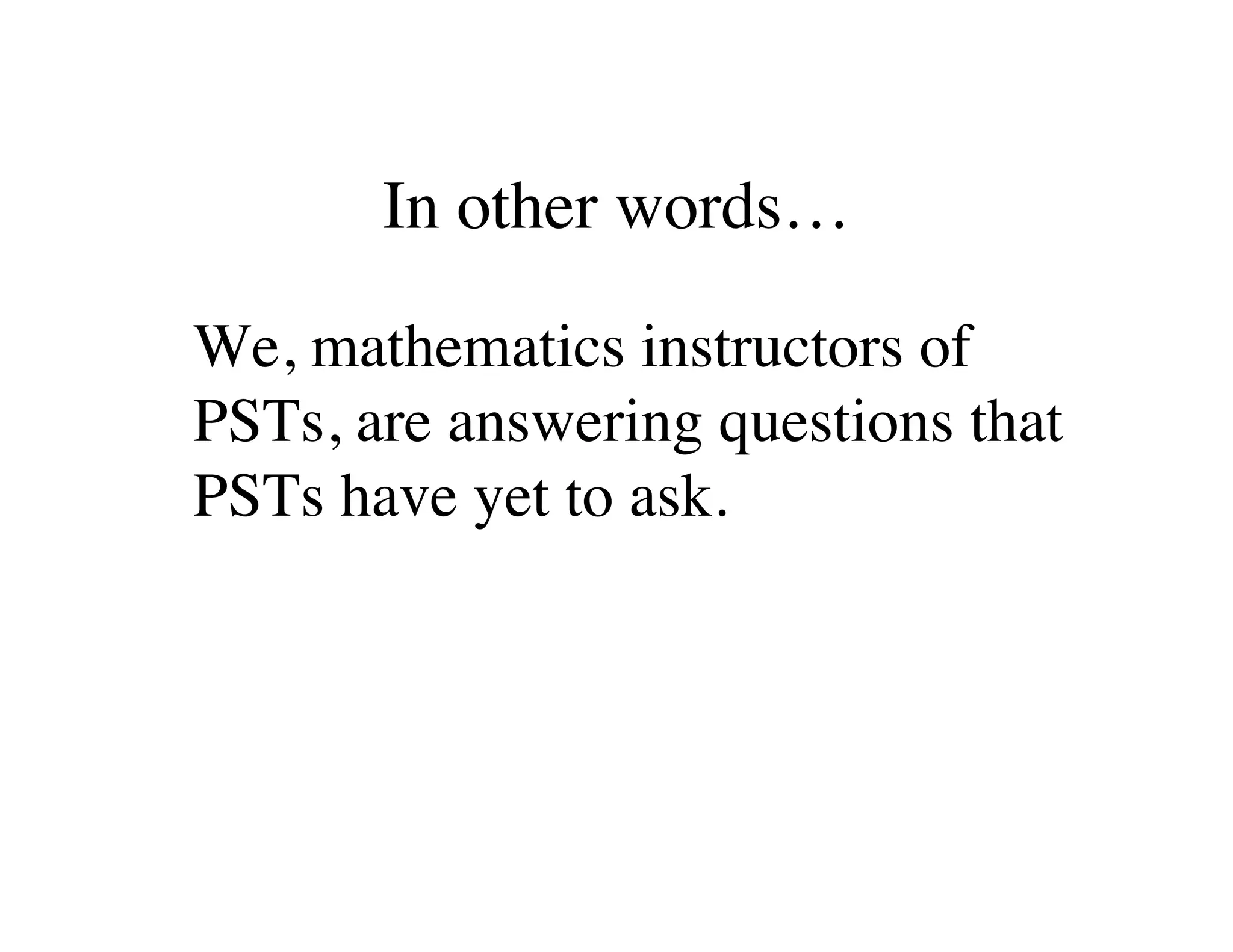

![One Representation of Javier’s Thinking

6 x 12

= (5 x 12) + (1 x 12)

= [(1

2

x 10) x 12] + 12

= [1

2

x (10 x 12)] + 12

= [1

2

x (120)] + 12

= 60 + 12

= 72

(Distributive prop. of x over +)

(Substitution property)

(Associative property of x)

Place value

What would a teacher need to know to

understand Javier’s thinking, and where do

teachers learn this?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/qwc5hktcgvdpwp1guzyw-signature-ad95e2248ce0b328f93e90463efa1e299db3423ce6a37df2f25301dada4a2fc7-poli-140924075046-phpapp01/75/Philipp-pm-slides-62-2048.jpg)