This document discusses phenylketonuria (PKU), a genetic disorder caused by a deficiency in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. This enzyme is needed to break down the amino acid phenylalanine. Without it, phenylalanine builds up to high levels in the blood and brain, which can cause intellectual disability if not treated early. The document outlines the causes, symptoms, diagnosis through newborn screening, and lifelong treatment through a phenylalanine-restricted diet for PKU patients. It also discusses milder forms that do not require dietary treatment and the rare cases caused by a deficiency in the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin.

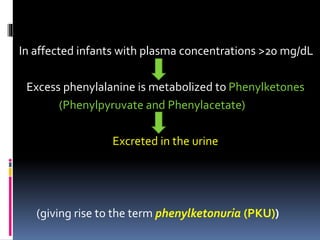

![ The severity of hyperphenylalaninemia depends on the

degree of enzyme deficiency .

May vary from very high plasma concentrations

( >20 mg/dL, classic phenylketonuria [PKU] ) to

mildly elevated levels, hyperphenylalaninemia

(2-6 mg/dL).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phenylketonuriapku-drpadmesh-150519122420-lva1-app6892/85/Phenylketonuria-PKU-Dr-Padmesh-3-320.jpg)