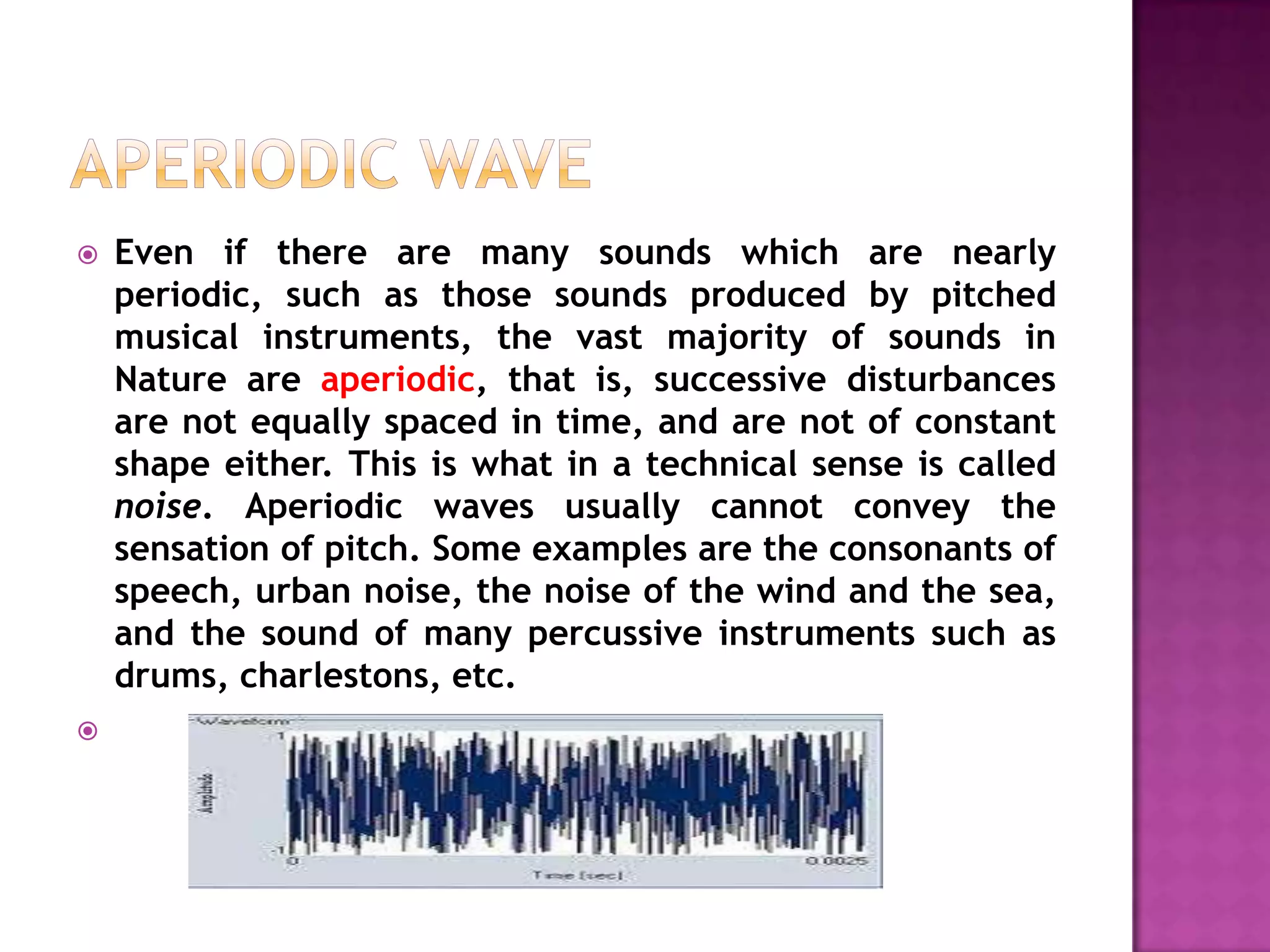

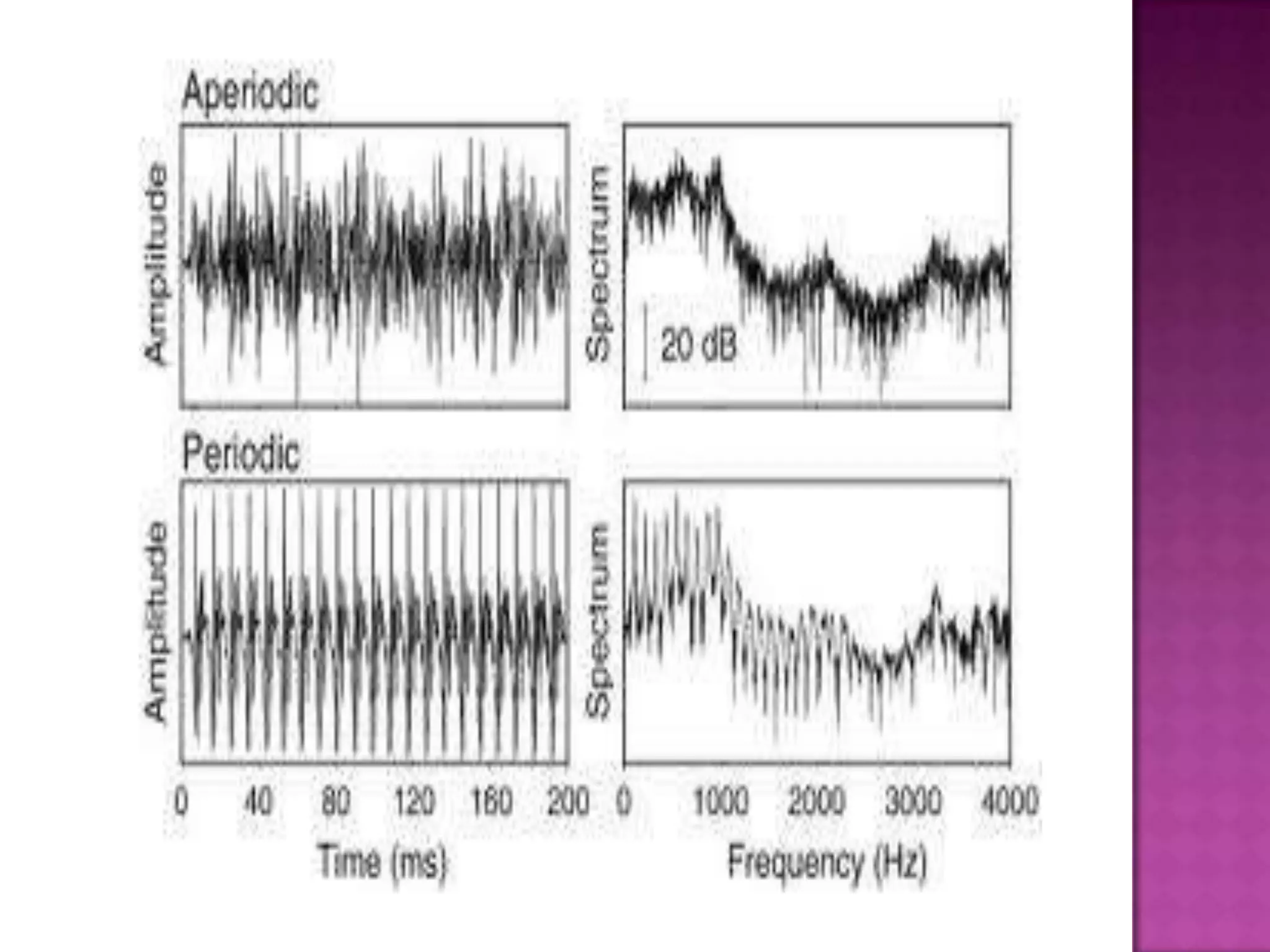

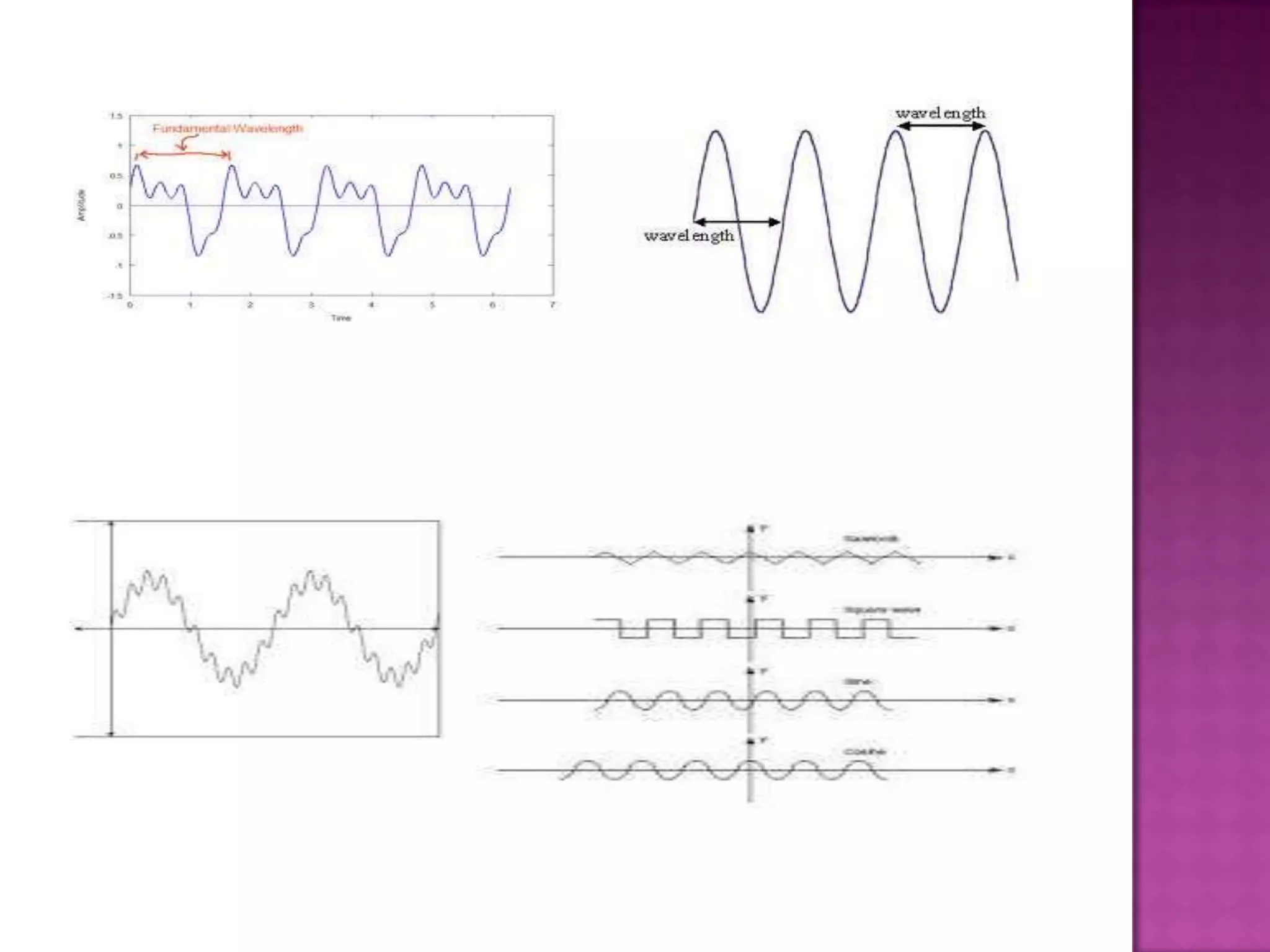

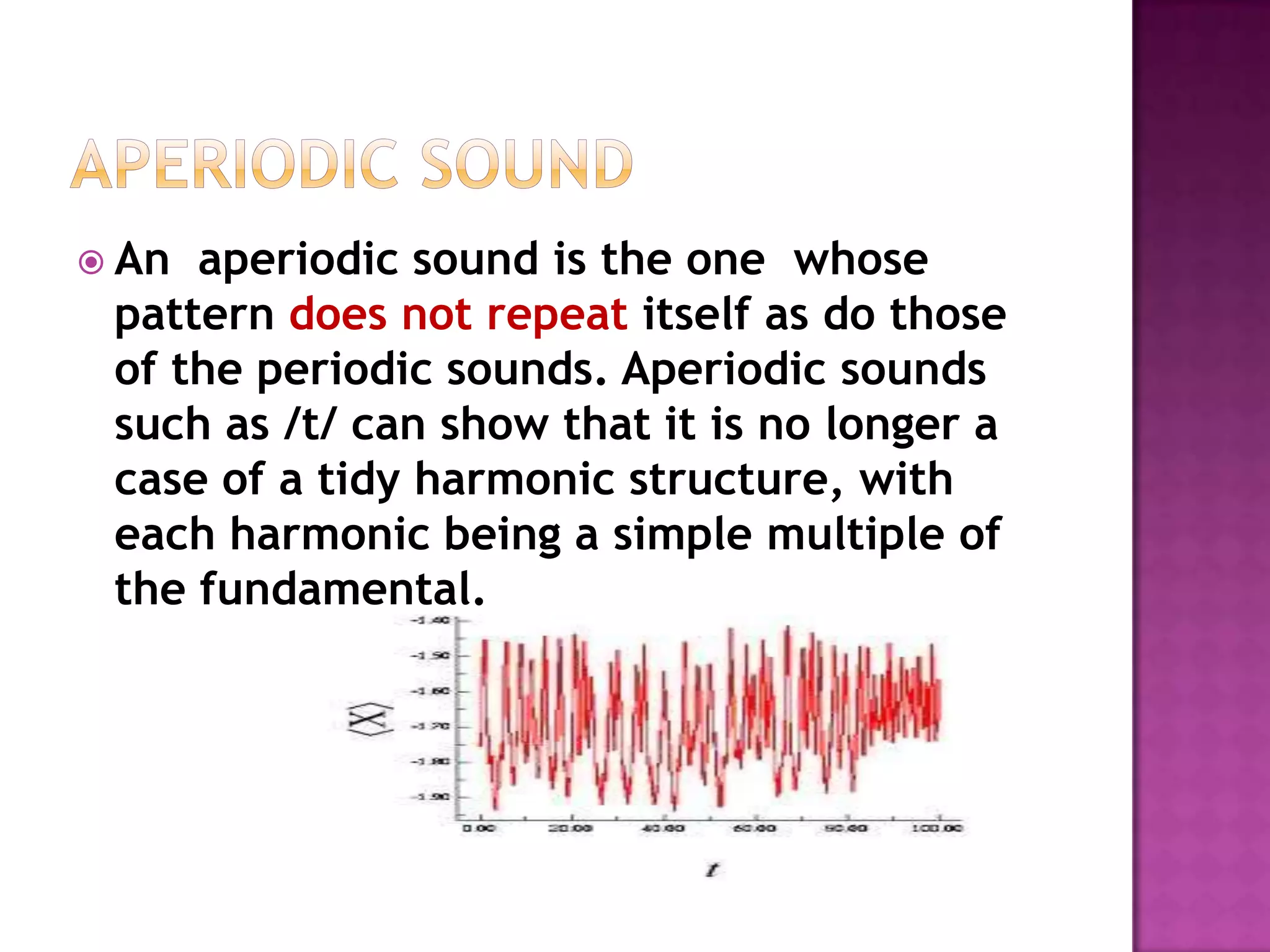

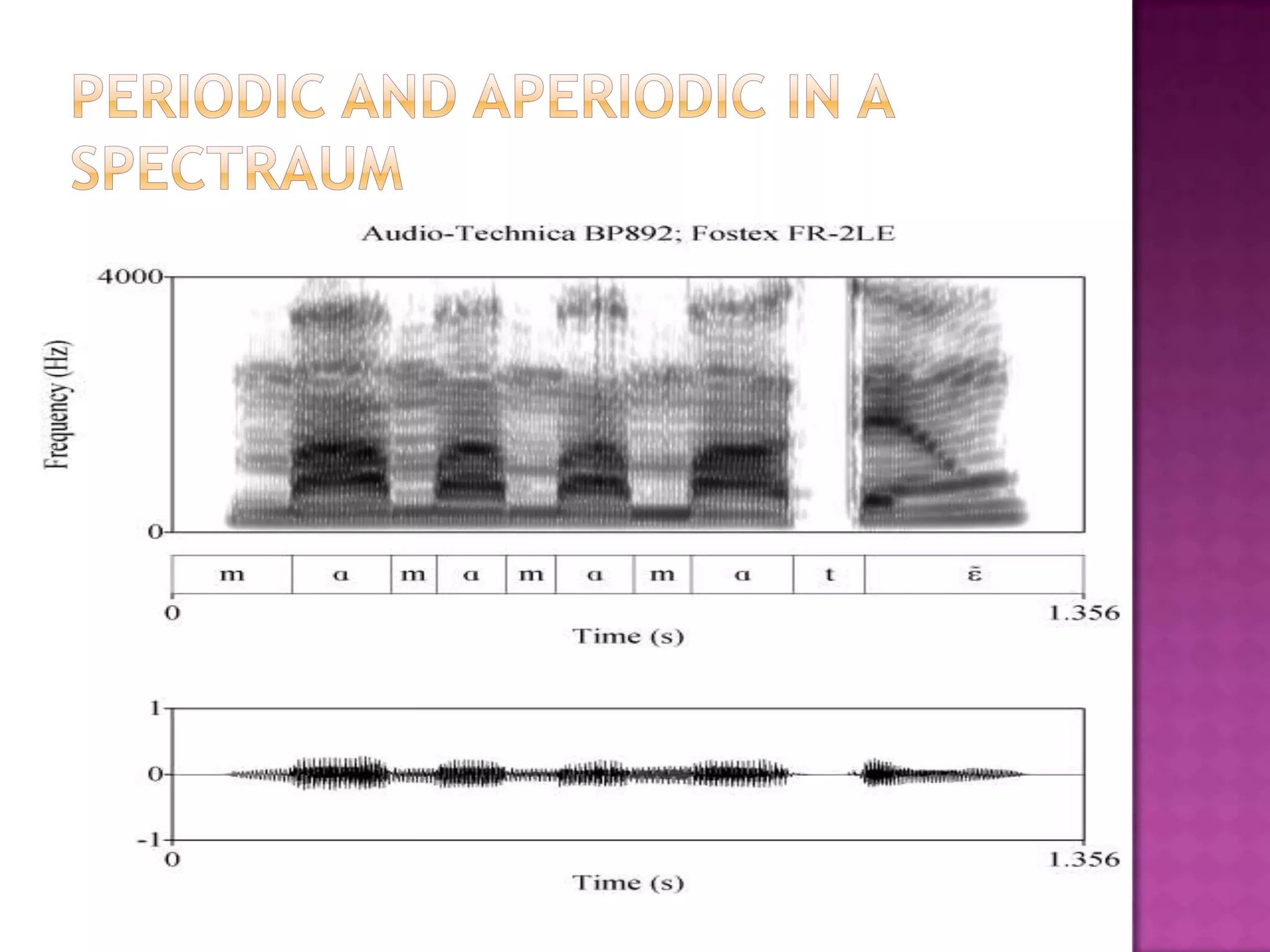

Sound is created by pressure disturbances traveling through an elastic medium like air. These pressure disturbances propagate as waves, which can be periodic or aperiodic. Periodic waves have regular, repeating patterns of vibration and are associated with the perception of pitch. They can be analyzed into combinations of sinusoidal components called harmonics. In contrast, aperiodic waves do not have a regular repeating pattern and are generally not associated with a clear pitch. Both periodic and aperiodic waves are important in speech communication.