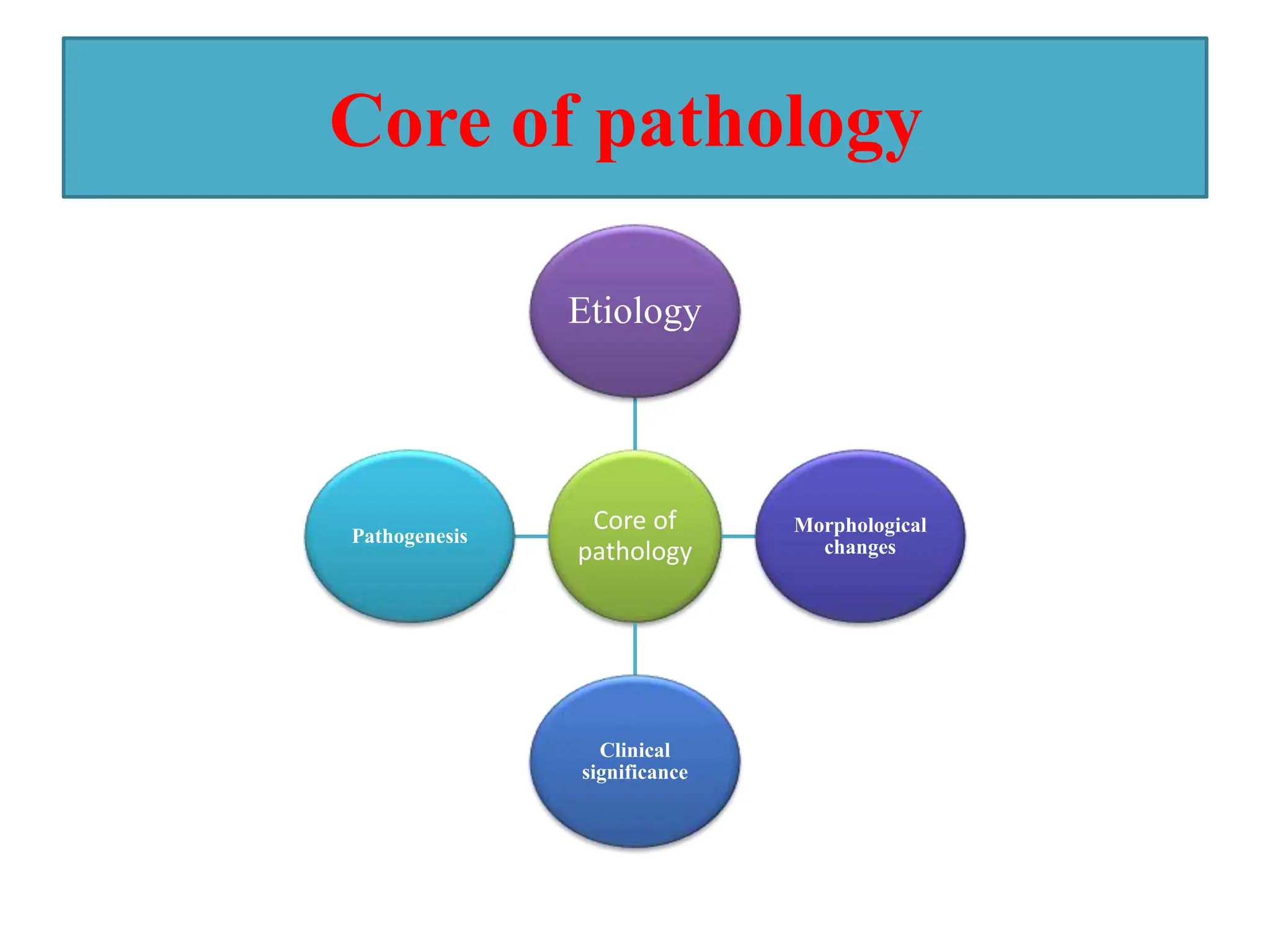

This document provides an overview of pathology and inflammation. It defines pathology as the scientific study of disease and outlines its main classifications. It also describes the core components of pathology including etiology, morphological changes, clinical significance, and pathogenesis. Different types of cell injuries, necrosis, and cellular adaptations such as atrophy, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and metaplasia are discussed. The document concludes with a definition and causes of inflammation.