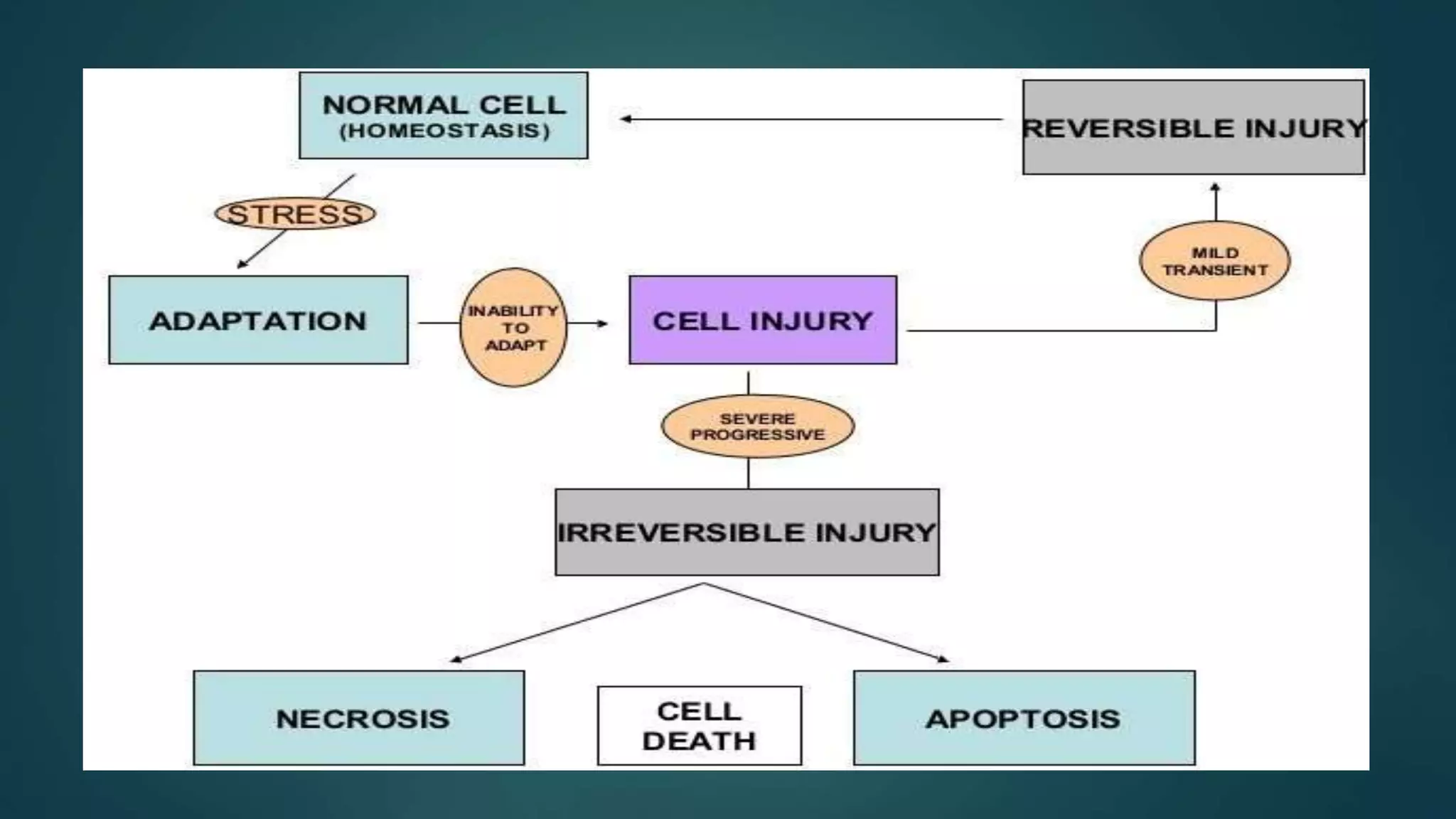

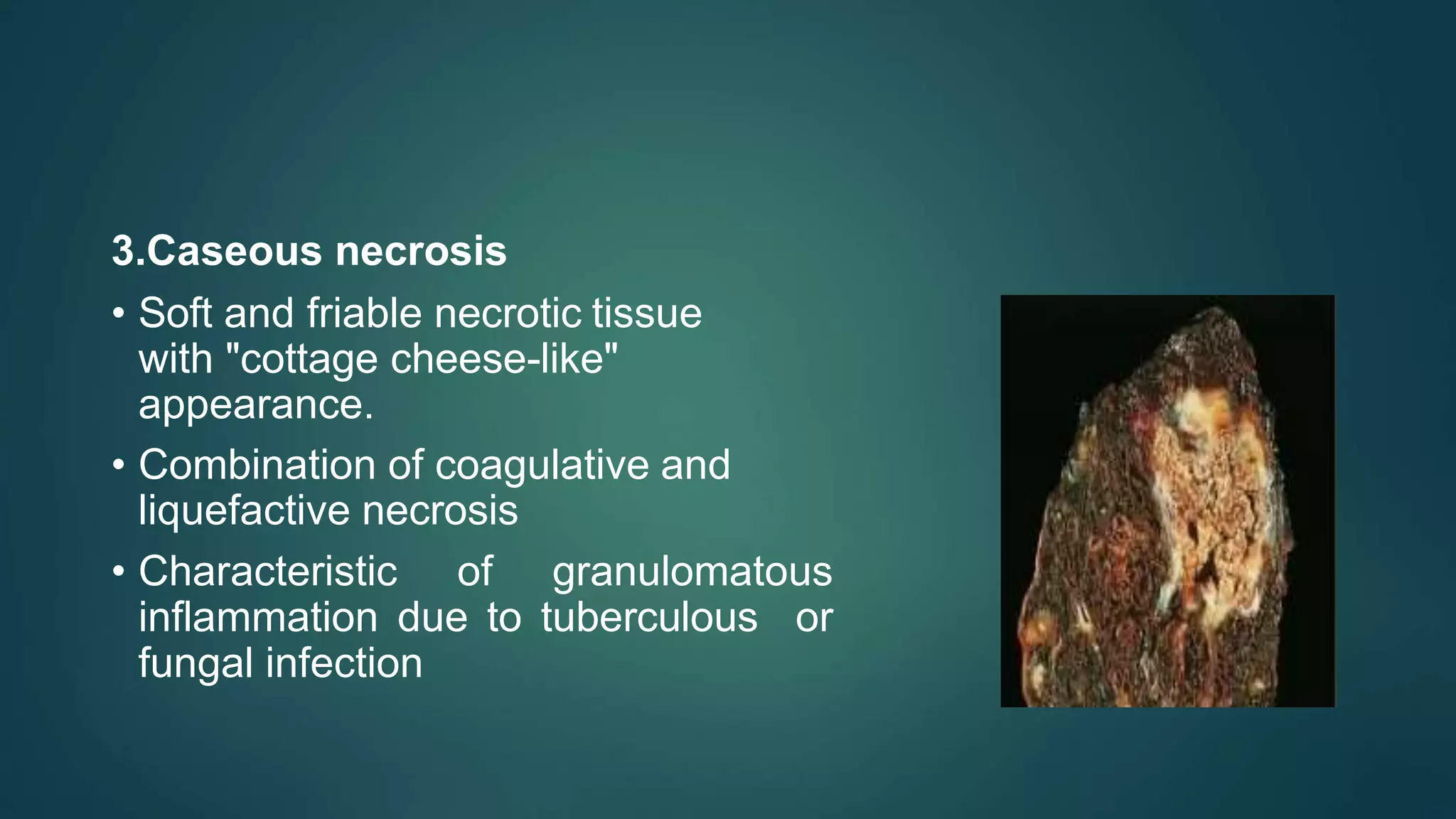

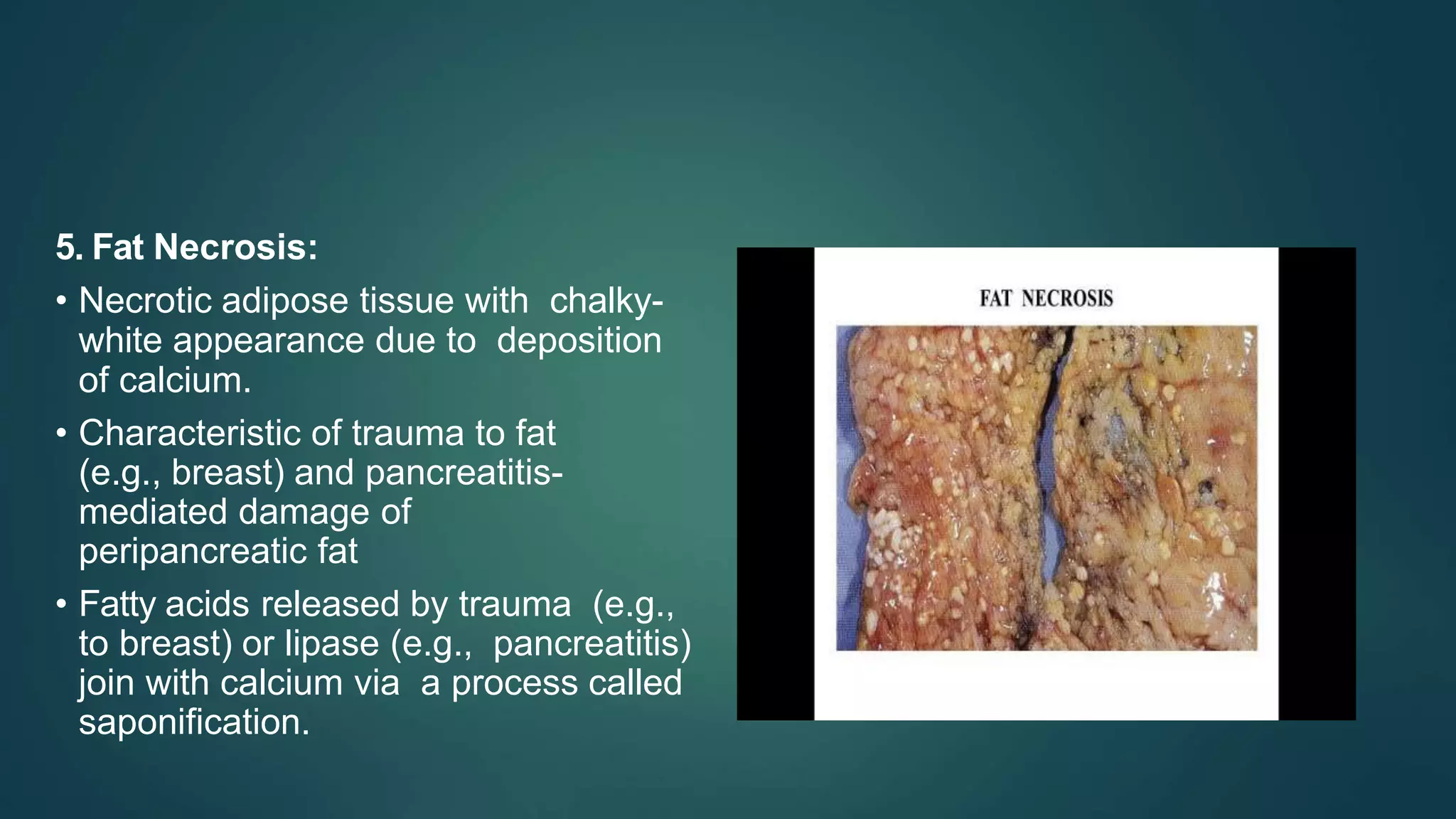

This document discusses cell adaptation, injury, and death. It describes how cells can adapt to stress through hypertrophy, hyperplasia, metaplasia, or atrophy. Prolonged or excessive stress can lead to cell injury, which is initially reversible but becomes irreversible over time due to membrane damage. The two main forms of cell death are necrosis, which is unprogrammed and inflammatory, and apoptosis, which is genetically programmed and does not induce inflammation. Necrosis can be coagulative, liquefactive, caseous, gangrenous, or fibrinoid depending on its characteristics.