The limbic system is a set of brain structures located in the middle of the brain involved in emotion, behavior, motivation, long-term memory, and olfaction. It includes the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and other structures. The limbic system regulates emotions and plays an important role in learning, memory, and emotional responses. It is involved in the formation of memories related to events with emotional significance. The limbic system also influences the autonomic nervous system and endocrine system in the regulation of responses to stress and threats to survival.

![106

Q: NEUROHORMONES

Hormone Stimulated

1. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) Adrenocorticotropic hormone

(ACTH)

2. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) Thyroid-stimulating hormone

(TSH)

3. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) Luteinizing hormone (LH)

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

4. Somatostatin (somatotropin release-inhibiting factor

[SRIF])

Growth hormone (GH)

5. Growth-hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) GH

6. Oxytocin Prolactin

7. Arginine vasopressin (AVP) ACTH

Neurohormones: a neuronal secretory product of neuroendocrine transducer cells of

the hypothalamus. Chemical signals cause the release of these neurohormones from

the median eminence of the hypothalamus into the portal hypophyseal bloodstream

and coordinate their transport to the anterior pituitary to regulate the release of target

hormones. Pituitary hormones, in turn, act directly on target cells (e.g., ACTH on the

adrenal gland) or stimulate release of other hormones from peripheral endocrine

organs.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

CRH, ACTH, and cortisol levels all rise in response to a variety of physical

and psychic stresses and serve as prime factors in maintaining homeostasis and

developing adaptive responses to novel or challenging stimuli.

The hormonal response depends both on the characteristics of the stressor itself

and on how the individual assesses and is able to cope with it. Aside from

generalized effects on arousal, distinct effects on sensory processing, stimulus

habituation and sensitization, pain, sleep, and memory storage and retrieval

have been documented. In primates, social status can influence adrenocortical

profiles and, in turn, be affected by exogenously induced changes in hormone

concentration.

Pathological alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function have been

associated primarily with mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and

dementia of the Alzheimer's type, substance use disorders as well.

Disturbances of mood are found in more than 50 percent of patients with

Cushing's syndrome (characterized by elevated cortisol concentrations), with

psychosis or suicidal thought apparent in more than 10 percent of patients

studied. Cognitive impairments similar to those seen in major depressive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-108-320.jpg)

![113

TUBERO-INFUNDIBULAR:DA acts as prolactin inhibitory factor.

Metabolism:It is specifically metabolized by MAO-B.The main product is Homovanillic acid(HVA).

Receptors:Two groups-First,coupled with Gs protein[D1,5] and other one is coupled with Gi

protein[D2-4].D2 is present in caudate nucleus,D3 in nucleus accumbens and D4 in frontal lobe(also

found in heart & kidney).

DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA:Based on the observation that anti-dopaminergics(the

phenothiazines) are effective in schizophrenia & drugs that cause DA release (amphetamines)can

cause psychosis in non-schizophrenics.Dec. levels of urine HVA is found in responders to

antipsychotics

However there is room for 5-HT in this regard as the Serotonin Dopamine antagonists(SDA) have come

up.DA is also implicated in psychosis due to brain tumors and mania.

DOPAMINE has also role in affective disorders,levels may be low in depression and high in

mania.This is supported by the fact that Amphetamines have antidepressant action.Some studies

have shown low levels of DA metabolites in the depressed.

The D2 receptors of caudate nucleus suppress caudate activity i.e gating of motor acts.Decreased

D2 receptors thus decr. motor activity excessively resulting in bradykinesia.On other hand excess

D2 activity removes gating control and cause extraneous motor acts like tics & also gives rise to

intrusive thoughts as seen in OCD.OCD pts show inc. caudate DA-analog binding.

It has been observed that the potency of typical antipsychotics correlated with D2 receptor

antagonism as also the EPS.They were also effective in controlling positive symptoms because they

could block D2 receptors in mesolimbic pathway but not the negative symptoms as in the

mesocortical region the predominant neurotransmitter was 5-HT.The SDA which were more

selective for 5 HT2 were more useful in these regard.

Also studies have documented an inverse relation between D2 receptors and emotional

detachment(negativity).So typical antipsychotics which lower D2 levels may actually worsen the

negative symtoms instead of treating them

Cocaine addiction is much dependant on dopamine for its pleasure-giving effects.DA transporter is

necessary for its action.It has been seen that D1 receptors inhibit the desire for cocaine while D2

have opposite action.

Nicotine also acts via release of DA and glutamate.Nicotine analogues are under experimental

study to treat Parkinsonism and to reduce cognitive deficites due to Haloperidol.

NORADRENERGIC/ADRENERGIC SYSTEM

Noradrenergic tracts in CNS:The NA cell bodies are mostly located in locus cerulus of pons and

lateral tegmental area.The axons project to neocortex,all parts of limbic

system,thalamus,hypothalamus and to cerebellum,spinal cord.Limbic system & spinal cord gets

innervation from both groups while hypothalamus & brainstem gets innervated by lateral

tegmental area.Most of these are NA-ergic while a few adrenergic neurones are found in caudal

pons and medulla.

Metabolism:Formed from DA with help of DA β-hydroxylase.NA is converted in adrenal medulla

into Adrenaline by enzyme PNMT.Both these products are metabolised by MAO(mainly MAOA)and

COMT.

Receptors:Broadly of two types α, β . α receptor is of 2 types α1 and α2.α1 is of three subtypes

α1A,α1B and α1D.α2 receptor is of three types α2A,α2B and α2C.β receptor is three types:β1,β2

and β3. α1-receptors are associated with PIP-cascade,while otherα-receptors decrease cAMP and

β-receptors seem to stimulate formation of cAMP.β1 ,2 counteract α-receptor action and β-3

receptors regulate energy metabolism.

The BIOGENIC AMINE THEORY for mood disorders is developed based on the fact that the drugs

that inhibit reuptake of NA and 5-HT are useful in depression. Drugs that affect both or only NA or

only 5-HT are all effective. It is seen from animal models that an intact NA system is essential for

drugs that act on 5-HT system and vice versa.This shows the action of these systems is interlinked

but unfortunately the interrelationship and individual roles of these systems in pathophysiology is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-115-320.jpg)

![114

still not very clear.

In social phobias,there is incr. release of NA(both centrally+peripherally) and increased sensitivity

to NA.Thus beta-blockers have role here.

Sleep disorders:The disease Narcolepsy is characterised by repeated intrusion of REM sleep during

daytime activities characterized by Cataplexy,Sleep paralysis and hypnagogic/hypnopompic

hallucinations.The NA-ergic system seems to be at fault in this case and α1-agonist Modanafil has

proved use in this case.This proves the role of NA in maintaining wakefulness and indeed bursting

of NAergic neurons are decreased in slow wave sleep and absent in REM sleep.Insomnia in anxiety

states is due to incr. NA levels.

The psychiatric drugs that are most commonly associated with NA system are the drugs which

inhibit uptake of NA(and 5-HT to lesser extent)i.e the tricyclic antidepressants,the MAOI(which

inhibit NA metabolism) as well as other atypical drugs e.g Venlafaxine[Inhibits α2-autoreceptors

and heteroceptors(on 5-HT neurones)],Mirtazapine(blocks presynaptic α2-

receptor),Bupropion(Also DA uptake inhibitor) and nefazodone.The TCAs at first cause inc.NA levels

which stimulate the α2 autoreceptors(thereby decreasing NA levels),then after 2-3 wks the

presynaptic autoreceptors get desensitized & normal firing ensues which leads to increased NA

conc. in synaptic cleft(due to reuptake inhibition) which correlates well with therapeutic

antidepressant effect.

The β -blockers are also used for psychiatric disorders such as social phobias,tremors(akathesia and

lithium induced).

The central sympatholytic property of Clonidine, α2-agonist has been used in opioid withdrawal.

The α2-antagonist Yohimbine is sometimes used to counteract the sexual adverse effects of SSRIs.

BIOGENIC AMINES FORMED FROM DEFINITE PRECURSORS

This category includes following neurotransmitters:

SEROTONIN(5-HT)

ACETYL CHOLINE

HISTAMINE

SEROTONERGIC SYSTEM

SEROTONERGIC TRACTS IN CNS:The major cell bodies of serotonergic neurones are located in

upper pons & midbrain-median and dorsal raphe nuclei,caudal locus cerulus,area postrema &

interpeduncular area.These neurones project to basal ganglia,limbic system & cerebral

cortex.Neurones from median raphe project to limbic system & from dorsal raphe project to

thalamus,striatum.Neocortex receives input from both groups.

SEROTONIN METABOLISM:The precursor amino acid is tryptophan,the availability of which is the

rate-limiting step.Dietary variation in tryptophan can effect 5-HT levels in brain e.g diet rich in

carbohydrate causes insulin release which stimulates tryptophan uptake and incr. 5-HT levels.Diet

rich in proteins cause the reverse effect.Tryptophan depletion causes irritability and hunger while

excess of it promotes sense of well-being.Tryptophan is converted to 5-HT by enzyme L-Tryptophan

hydroxylase.Synthesized 5-HT is packaged into granules for release on depolarization.Action is

ended by reuptake into presynaptic membrane by a transporter,genetic polymorphism of which

creates 2-4% of the biological variation inlevels of anxiety.5-HT activity is absent in REM sleep.

Once its action is over,5-HT is catabolized by MAO-A isozyme to form 5-HIAA.

SEROTONERGIC RECEPTORS:Previously only 2 types were known-5-HT1 and 5-HT2(on basis of

affinity for 5-H3T),but now 14 different subtypes are known.These are broadly divided to two

types:

A)Ion-channel dependant:includes 5-HT3.It is associated with Na+ rel. on activation.

B)G-Protein coupled:These are of two subtypes,those involved with the IP3-DAG pathway(includes 5-

HT2) and cAMP pathway(5-HT1 and 5-HT4-7).These may be inhibitory type(5-HT1,5) or excitatory(5-

HT4,6,7).The inhibitory ones decrease cAMP and excitatory ones increase cAMP.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-116-320.jpg)

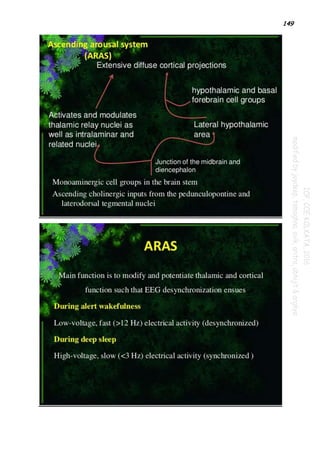

![146

FUNCTIONS OF RETICULAR FORMATIONS:

Regulating Sleep-Wake Transitions

The physiological change from a state of deep sleep to wakefulness is reversible and mediated by

the RAS.[3] Inhibitory influence from the brain is active at sleep onset, likely coming from the

preoptic area (POA) of the hypothalamus. During sleep, neurons in the RAS will have a much lower

firing rate; conversely, they will have a higher activity level during the waking state. Therefore, low

frequency inputs (during sleep) from the RAS to the POA neurons result in an excitatory influence

and higher activity levels (awake) will have inhibitory influence. In order that the brain may sleep,

there must be a reduction in ascending afferent activity reaching the cortex by suppression of the

RAS.

Attention

The reticular activating system also helps mediate transitions from relaxed wakefulness to periods

of high attention.[6] There is increased regional blood flow (presumably indicating an increased

measure of neuronal activity) in the midbrain reticular formation (MRF) and thalamic intralaminar

nuclei during tasks requiring increased alertness and attention.Refer the 2 snap shot portion

immediately below...](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-148-320.jpg)

![174

there must be a reduction in ascending afferent activity reaching the cortex by suppression of the

RAS.

Attention

The reticular activating system also helps mediate transitions from relaxed wakefulness to periods

of high attention. There is increased regional blood flow (presumably indicating an increased

measure of neuronal activity) in the midbrain reticular formation (MRF) and thalamic intralaminar

nuclei during tasks requiring increased alertness and attention.

Clinical Relevance

Anesthetic Effects

One intuitive hypothesis, first proposed by Magoun, is that anesthetics might achieve their potent

effects by reversibly blocking neural conduction within the reticular activating system, thereby

diminishing overall arousal. However, further research has suggested that selective depression of

the RAS may be too simplistic an explanation to fully account for anesthetic effects. This remains

a major unknown and point of contention between experts of the reticular activating system.[citation

needed]

Pain

Direct electrical stimulation of the reticular activating system produces pain responses in cats and

educes verbal reports of pain in humans.[citation needed] Additionally, ascending reticular

activation in cats can produce mydriasis,[citation needed] which can result from prolonged pain.

These results suggest some relationship between RAS circuits and physiological pain pathways.

Developmental Influences

There are several potential factors that may adversely influence the development of the reticular

activating system:

Regardless of birth weight or weeks of gestation, premature birth induces persistent deleterious

effects on pre-attentional (arousal and sleep-wake abnormalities), attentional (reaction time and

sensory gating), and cortical mechanisms throughout development.

Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke is known to produce lasting arousal, attentional and cognitive

deficits in humans. This exposure can induce up-regulation of nicotinic receptors on α4b2 subunit

on Pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) cells, resulting in increased tonic activity, resting membrane

potential, and hyperpolarization-activated cation current. These major disturbances of the intrinsic

membrane properties of PPN neurons result in increased levels of arousal and sensory gating deficits](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-176-320.jpg)

![196

2. NREM Sleep

-EEG of NREM sleep is characterized by sleep spindles, K-complexes, slow waves (.5 to 2 Hz), and

slow oscillations (mainly 0.7 to 1 Hz).

-Brain activation generally decreases in NREM sleep, particularly SWS, characterized by an overall

decrease in cerebral blood flow.

-PET imaging studies show the deactivation of many structures, including the brainstem, thalamus,

anterior hypothalamus, basal forebrain, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and frontal, parietal, and

mesiotemporal cortical areas.

-The control of NREM sleep involves multiple structures ranging from the lower brainstem through

the thalamus, hypothalamus, and forebrain.

-The generation of sleep oscillations is mediated by cortico-cortical, cortico-thalamo-cortical, and

thalamoreticular loops.

-Shortly before the transition from waking to sleep, changes in the activity of cholinergic,

noradrenergic, histaminergic, hypocretinergic, and glutamatergic neuromodulatory systems with

diffuse projections to the ARAS bring about a change in the firing mode of thalamic and cortical

neurons.

-Thalamocortical cells are hyperpolarized, whereas reticulothalamic cells are facilitated and

further inhibit thalamocortical cells, with the consequence that sensory stimuli are gated at the

thalamic level and often fail to reach the cortex. Rebound firing due to the activation of intrinsic

currents in thalamocortical cells leads to the emergence of oscillations.

-Intracellular recordings have shown that the slow oscillation is the result of a brief

hyperpolarization of cortical neurons. The hyperpolarization phase, also known as the down state,

is followed by a slightly longer depolarization phase, known as the up state, during which the firing

of cortical neurons entrains and synchronizes spindle sequences in thalamic neurons, resulting in

EEG-detectable spindles.

-K-complexes are made up of the cortical depolarization phase followed by its triggered spindle.

-The slow oscillation also organizes delta waves, which can be generated both within the thalamus

and in the cortex.

-The importance of hypothalamic structures for sleep induction is recognized in early studies.

Electrical stimulation of the anterior hypothalamus resulted in increased slow wave activity

in the cortex.

In encephalitis lethargica lesions occurred in the anterior hypothalamus and were

characterized by severe insomnia.

The ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO)[part of ant. Hypothalamus] may be a possible sleep

switch.

Neurons scattered through the anterior hypothalamus and the basal forebrain, also play a

major role in initiating and maintaining sleep.

These neurons when active, release γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and the peptide galanin

and inhibit most wakefulness-promoting areas.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-198-320.jpg)

![239

Temporal lobe epilepsy

Temporal lobe epilepsy is a form of focal epilepsy, a chronic neurological condition

characterized by recurrent seizures. They fall into two main categories: partial-onset

(focal or localization-related) epilepsies and generalized-onset epilepsies. Partial-

onset epilepsies account for about 60% of all adult epilepsy cases.

Temporal lobe epilepsies are a group of medical disorders in which persons

experience recurrent epileptic seizures arising from one or both temporal lobes of

the brain. Two main types are recognized according to the International League

Against Epilepsy[ILAE]-

• Medial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE) : arises in the hippocampus,

parahippocampal gyrus and amygdale which are located in the inner aspect of the

temporal lobe.

• Lateral temporal lobe epilepsy (LTLE) : arises in the neocortex on the outer surface

of the temporal lobe of the brain.

Because of strong interconnections, seizures beginning in either the medial or

lateral temporal areas often spread to involve both areas and also to neighboring

areas on the same side of the brain as well as the temporal lobe on the opposite side

of the brain. Temporal lobe seizures can also spread to the adjacent frontal lobe and

to the parietal and occipital lobes.

Symptoms

The symptoms felt by the person, and the signs observable by others, during seizures

which begin in the temporal lobe depend upon the specific regions of the temporal

lobe and neighboring brain areas affected by the seizure. The International League

Against Epilepsy (ILAE) recognizes three types of seizures which persons with TLE

may experience.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/paper1part2-210910204808/85/Paper-1-part-2-241-320.jpg)