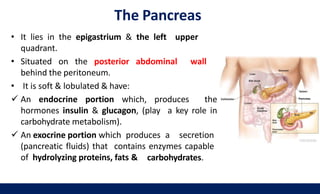

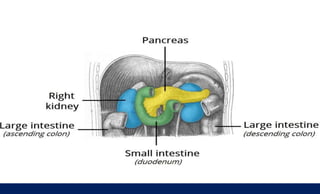

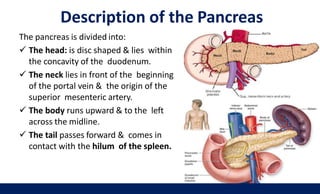

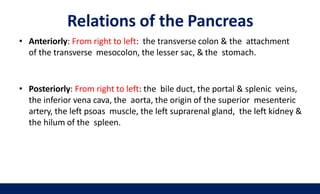

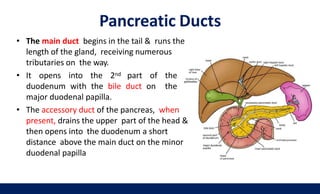

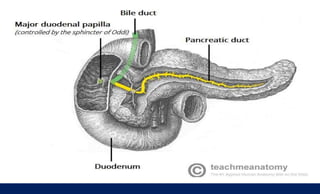

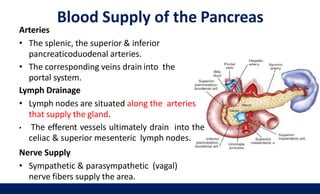

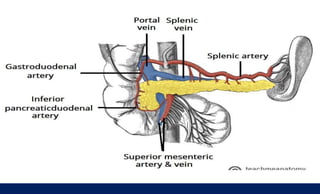

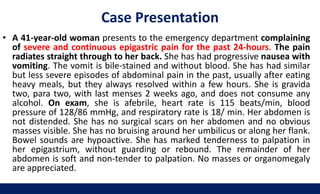

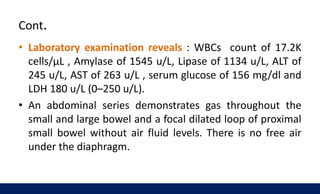

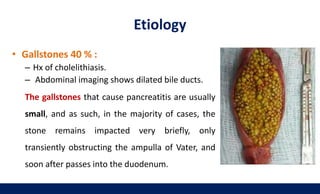

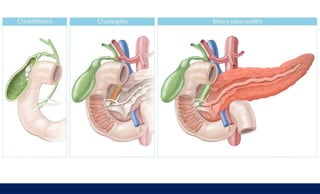

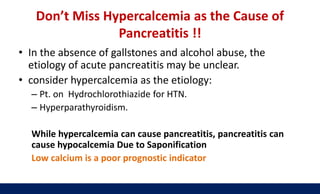

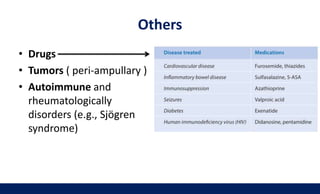

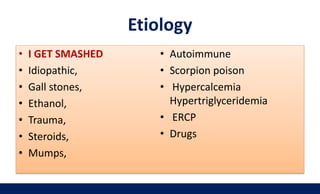

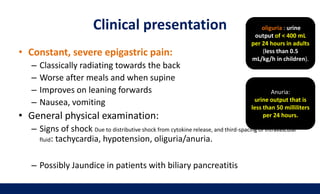

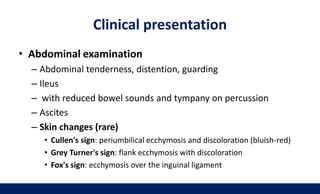

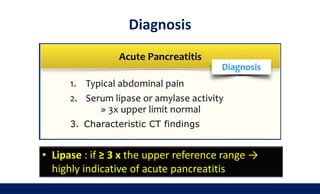

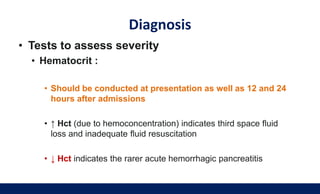

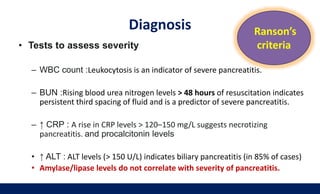

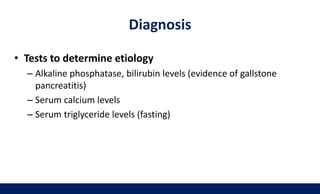

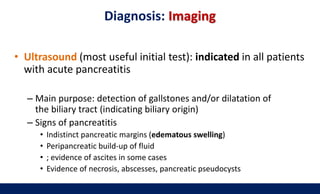

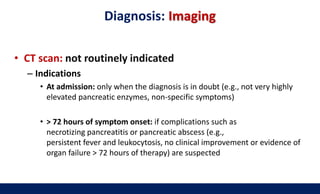

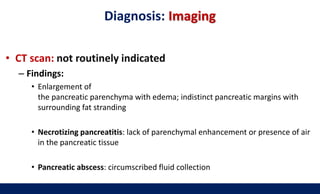

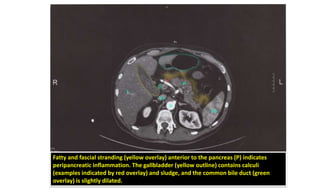

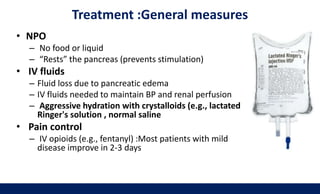

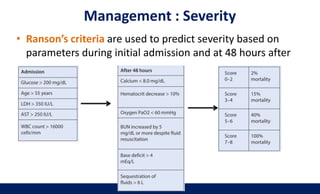

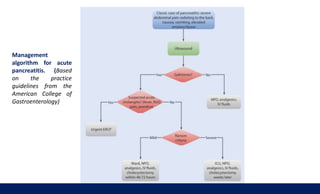

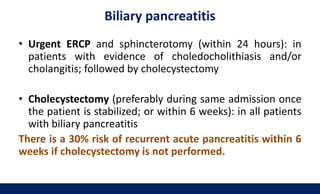

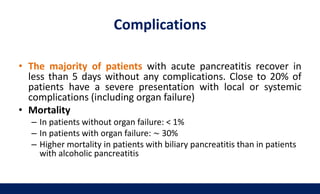

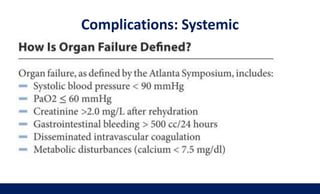

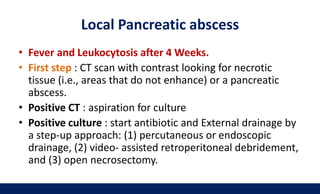

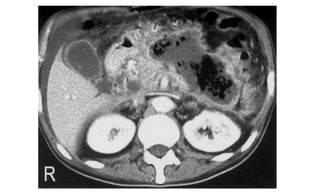

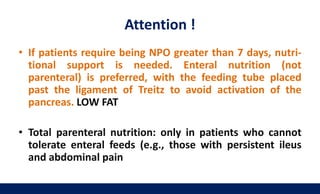

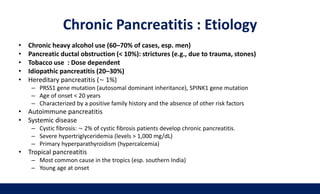

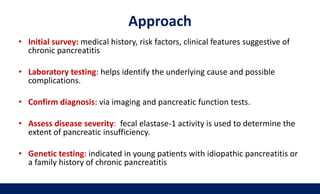

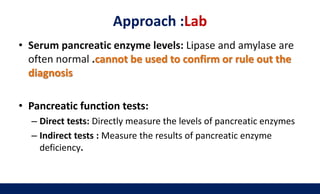

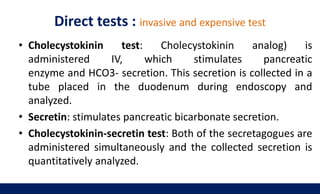

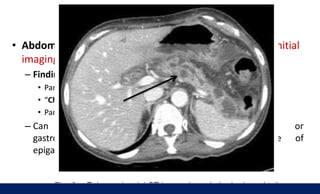

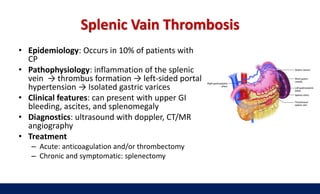

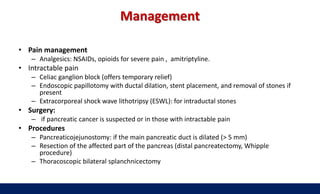

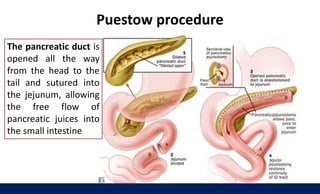

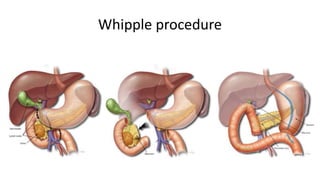

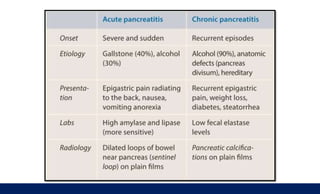

The document provides a detailed overview of pancreatitis, covering both acute and chronic forms, along with anatomy, causes, differential diagnoses, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. It discusses the anatomy of the pancreas, common causes of pancreatitis such as gallstones and alcohol, and emphasizes the importance of differentiating between various potential complications. It also outlines the management and interventions required for acute pancreatitis, including urgent procedures for biliary pancreatitis, and highlights the clinical implications of chronic pancreatitis.