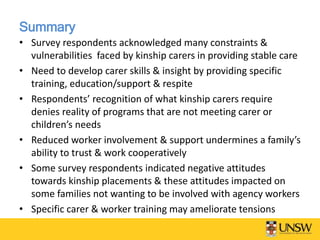

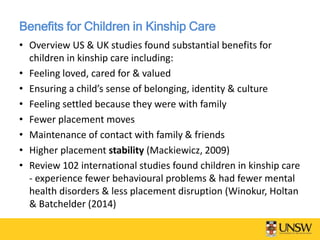

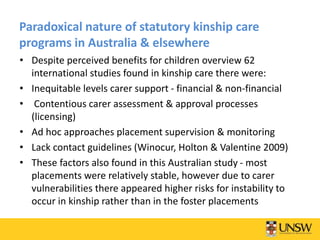

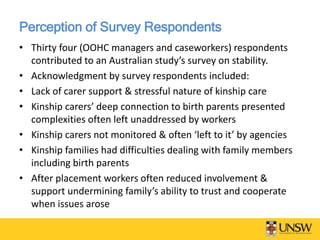

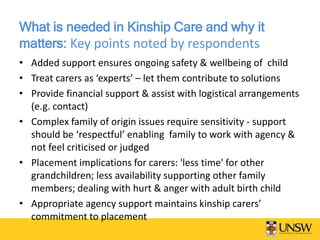

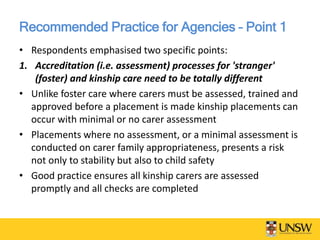

This document summarizes a study on resolving tensions between kinship carers and workers in statutory kinship care in Australia. It finds that while kinship care provides benefits for children, there are also challenges as kinship carers receive less support than foster carers. Survey respondents noted kinship carers need more training, education, and respite support to develop skills and manage complex family dynamics. The document recommends agencies take different approaches with kinship care, including assessing carers, providing financial support, and connecting carers to support groups, to best support placement stability and meet children's and carers' needs.

![Recommended Practice for Agencies - Point 2

2. Welfare agencies need to undertake fundamentally different

roles in foster & kinship care placements

Kinship care is unique. It is not foster care. At the same time it

is more than family support ... carers will need a model of

support which recognises the child, parents and kinship carers

as part of a family system with its own strengths, networks

and needs ... there is a strong case for redefining kinship care

as a separate category [with its set of regulations and

guidance] of looked after children ... this would be a major

step forward in recognising the commitment of kinship carers

to the child they have taken into their care. (Aldgate and

McIntosh (2006: 145)

• Agencies require specific kinship care workers for this role](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p1fp31mchugh-150520082249-lva1-app6891/85/Resolving-Tensions-between-Carers-and-Workers-in-Statutory-Kinship-Care-an-Australian-Study-11-320.jpg)