Pearson is a global learning company active in 70 countries, recognized for its collaboration with educators to enhance teaching and learning experiences. The document outlines products and services aimed at improving educational outcomes, particularly in higher education and K-12. It includes a comprehensive guide to engineering mathematics, covering topics from algebra to complex analysis.

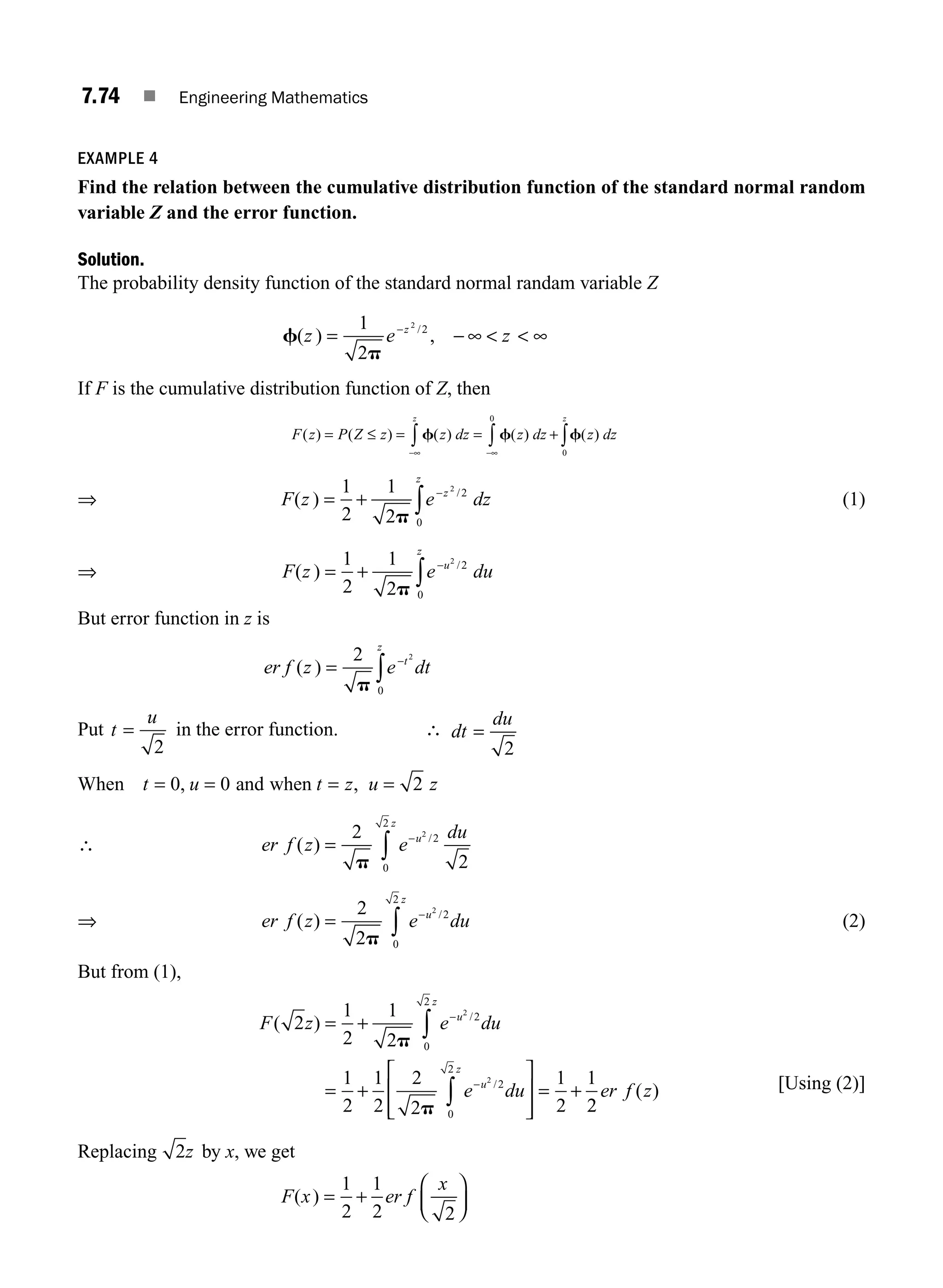

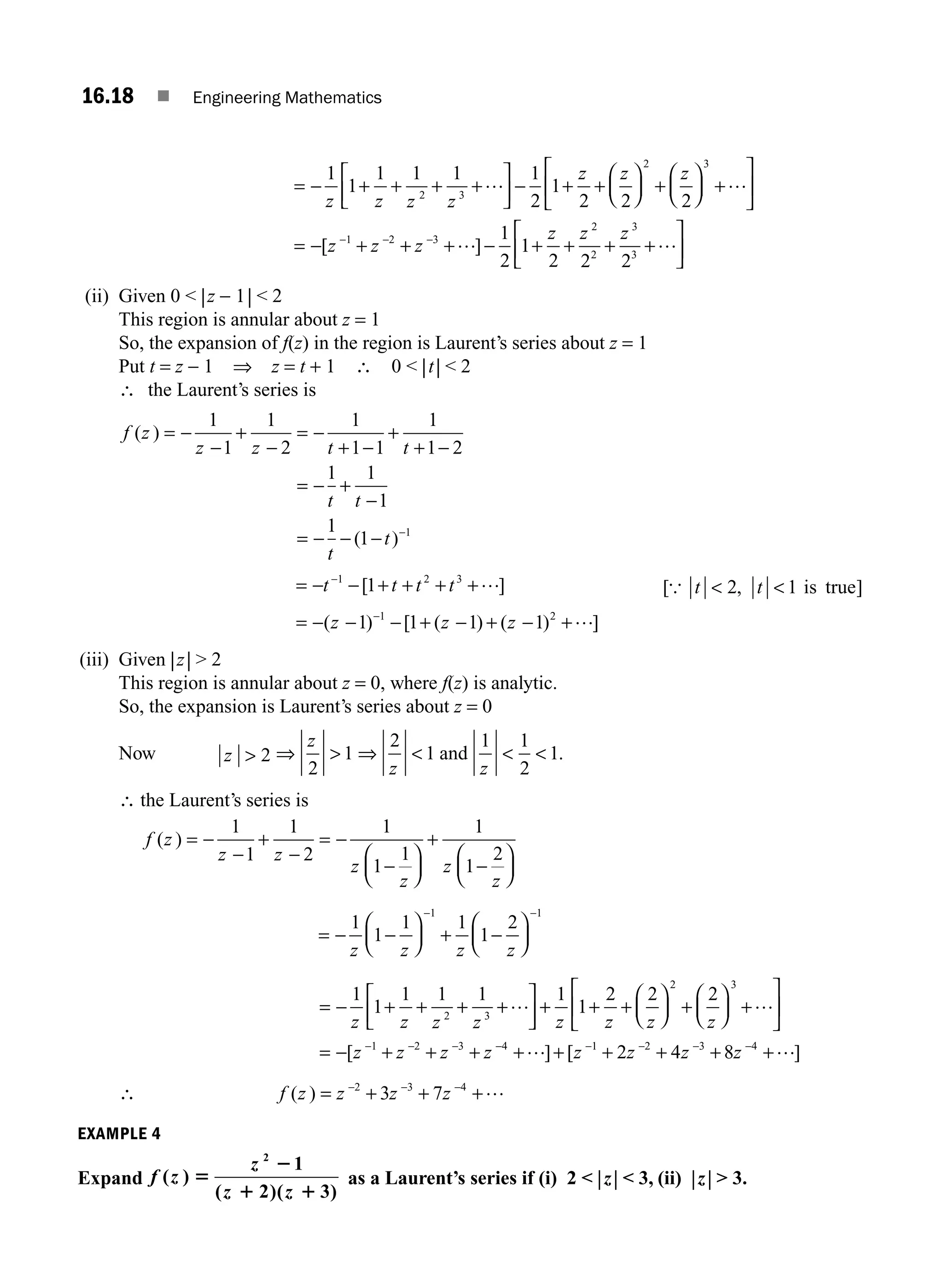

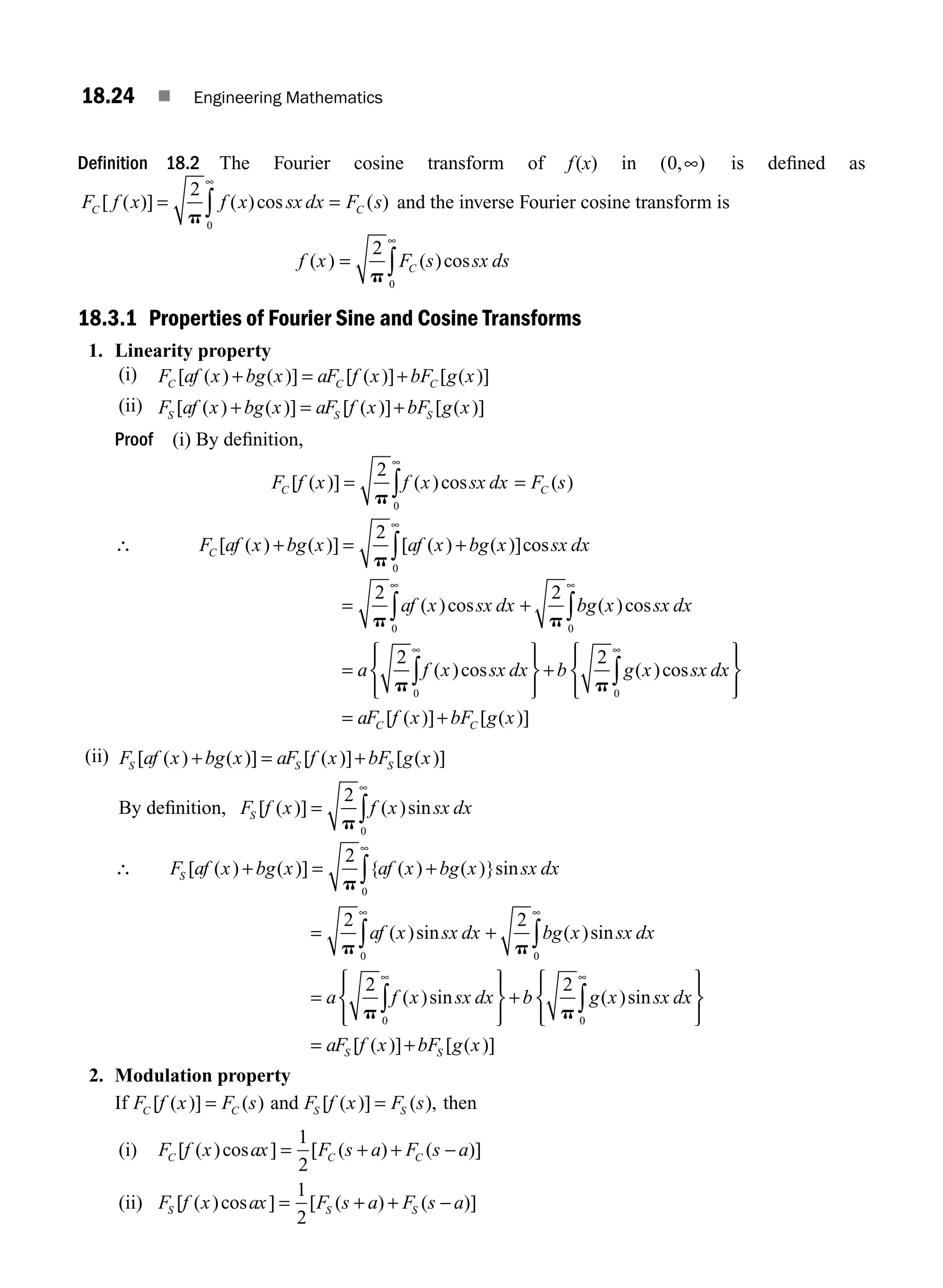

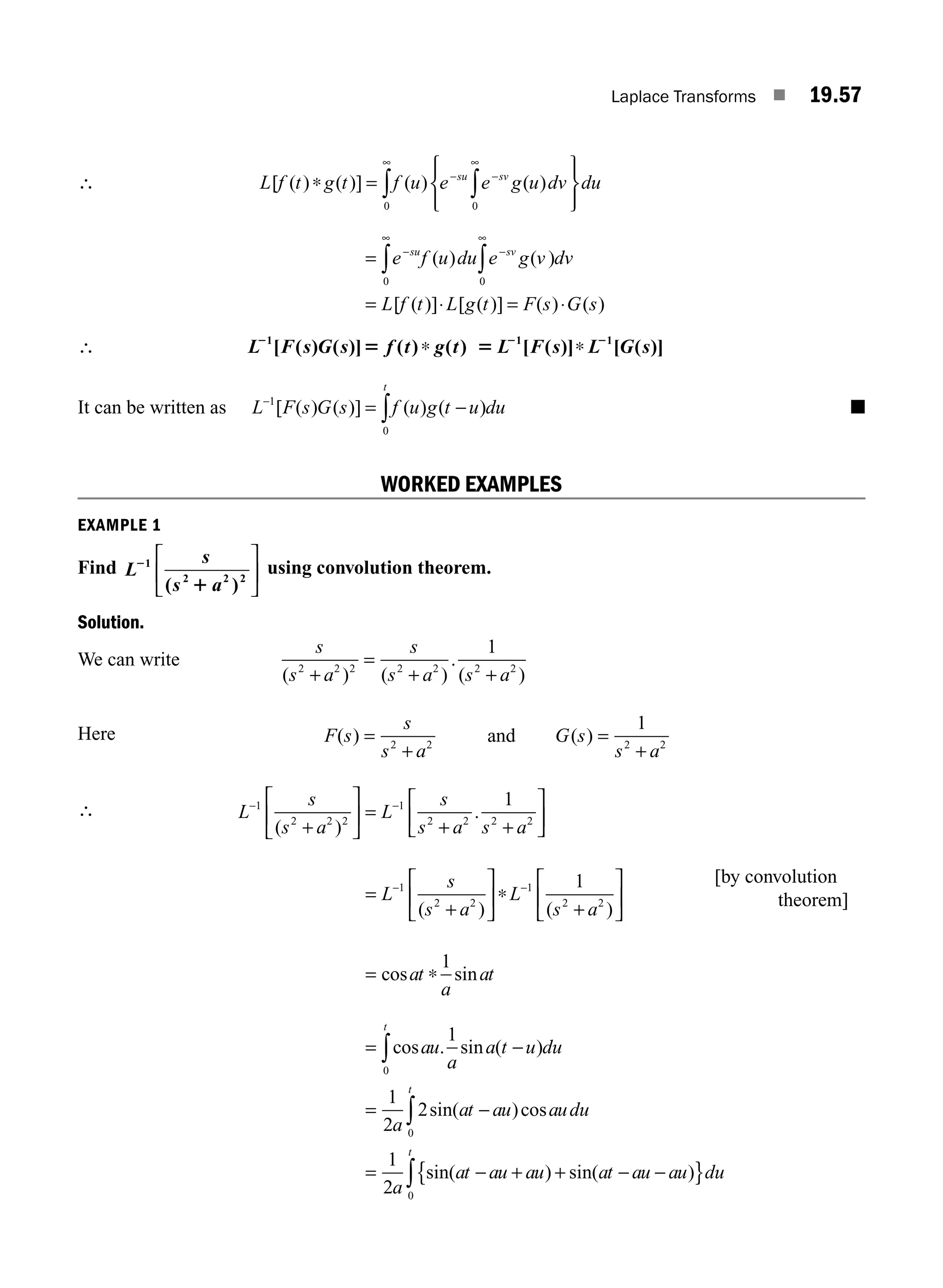

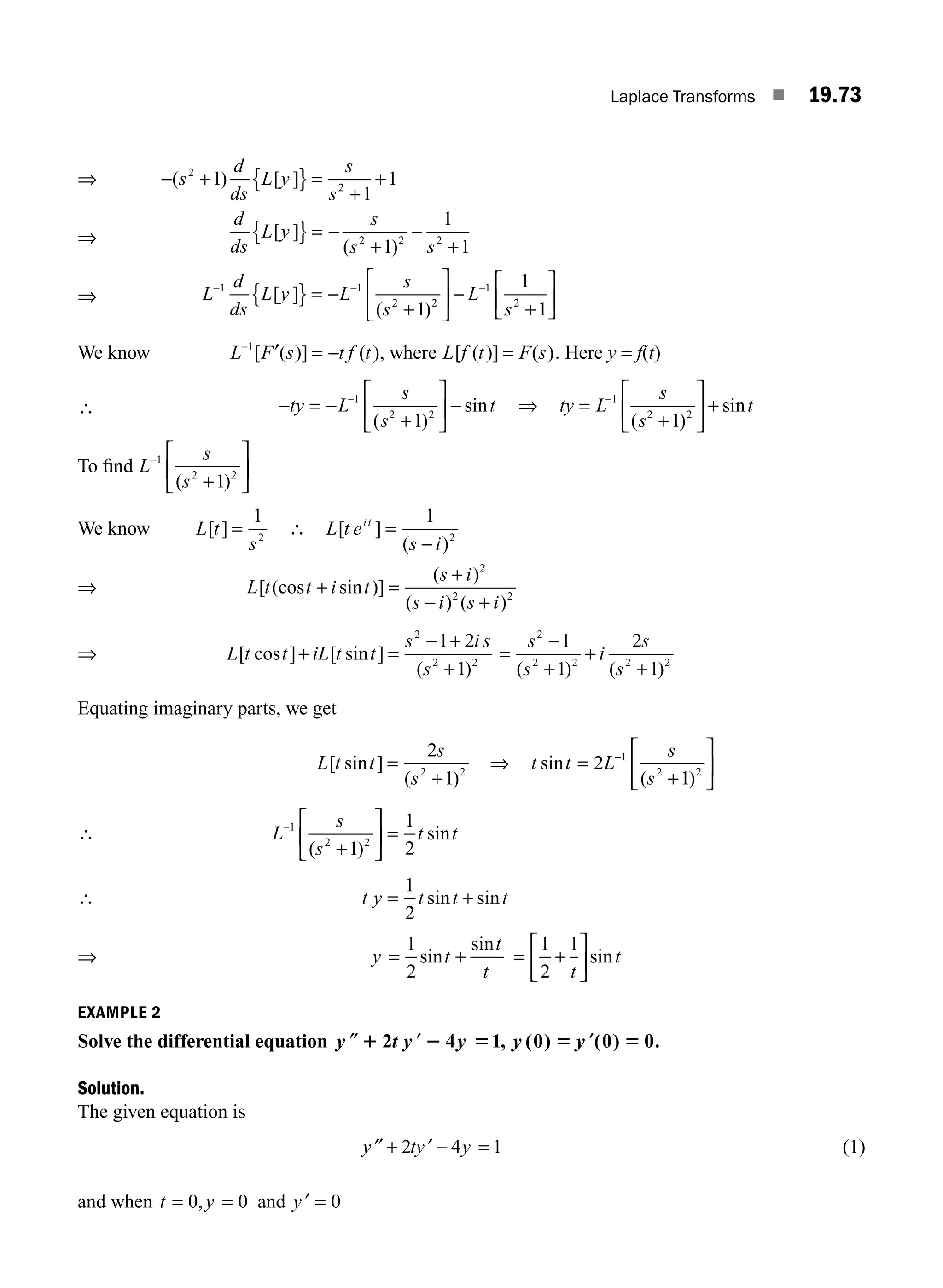

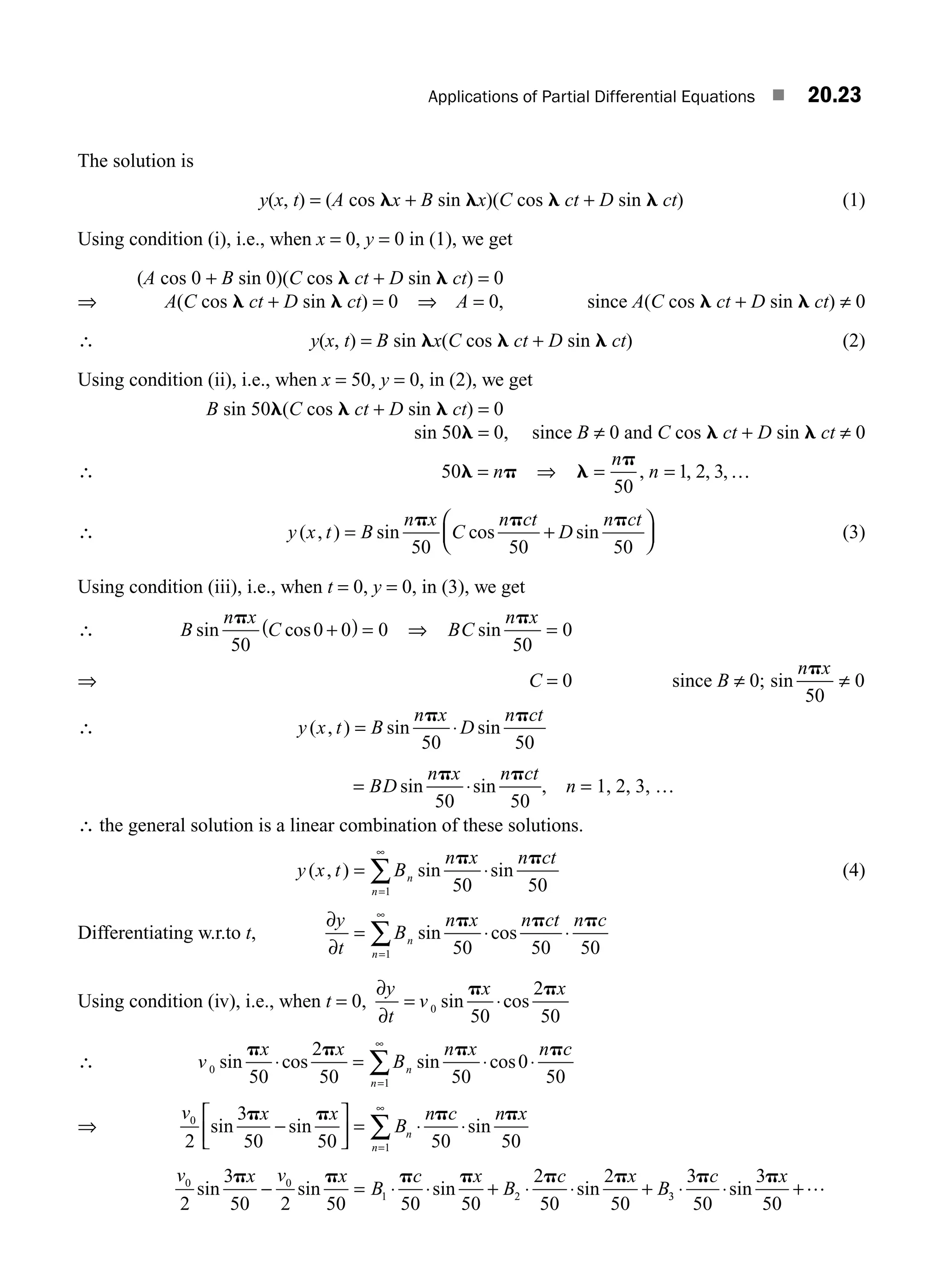

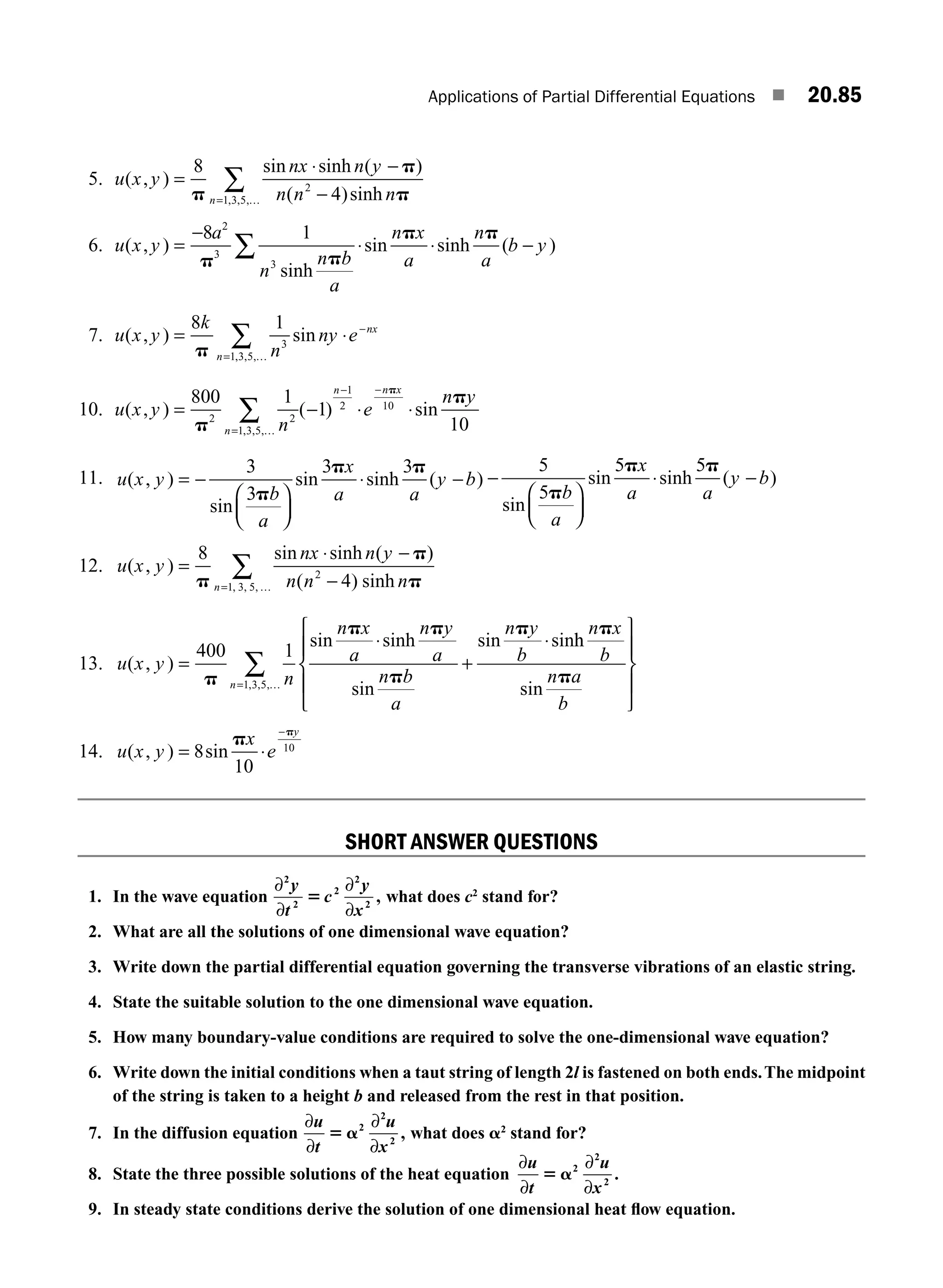

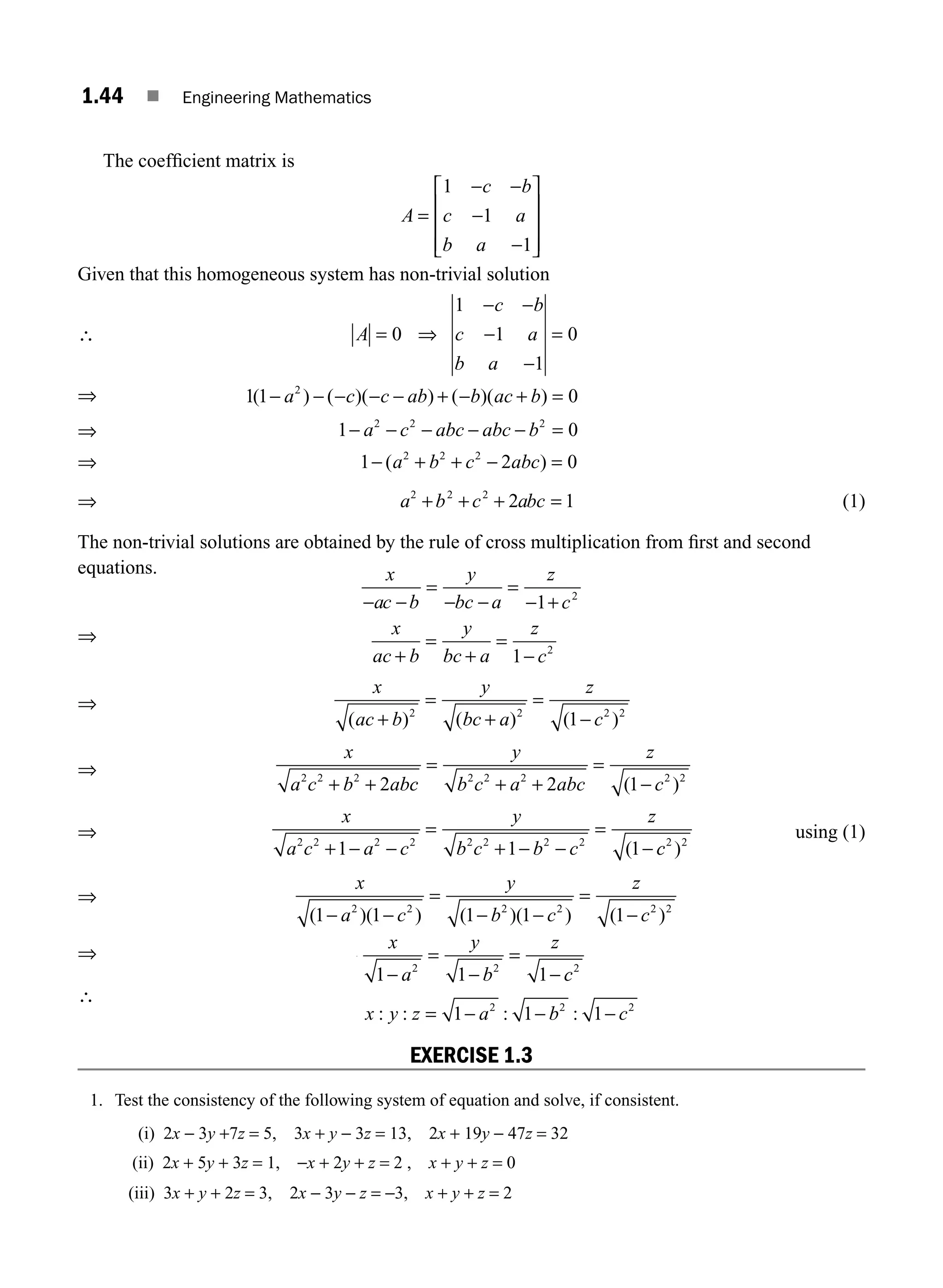

![xxiv n Contents

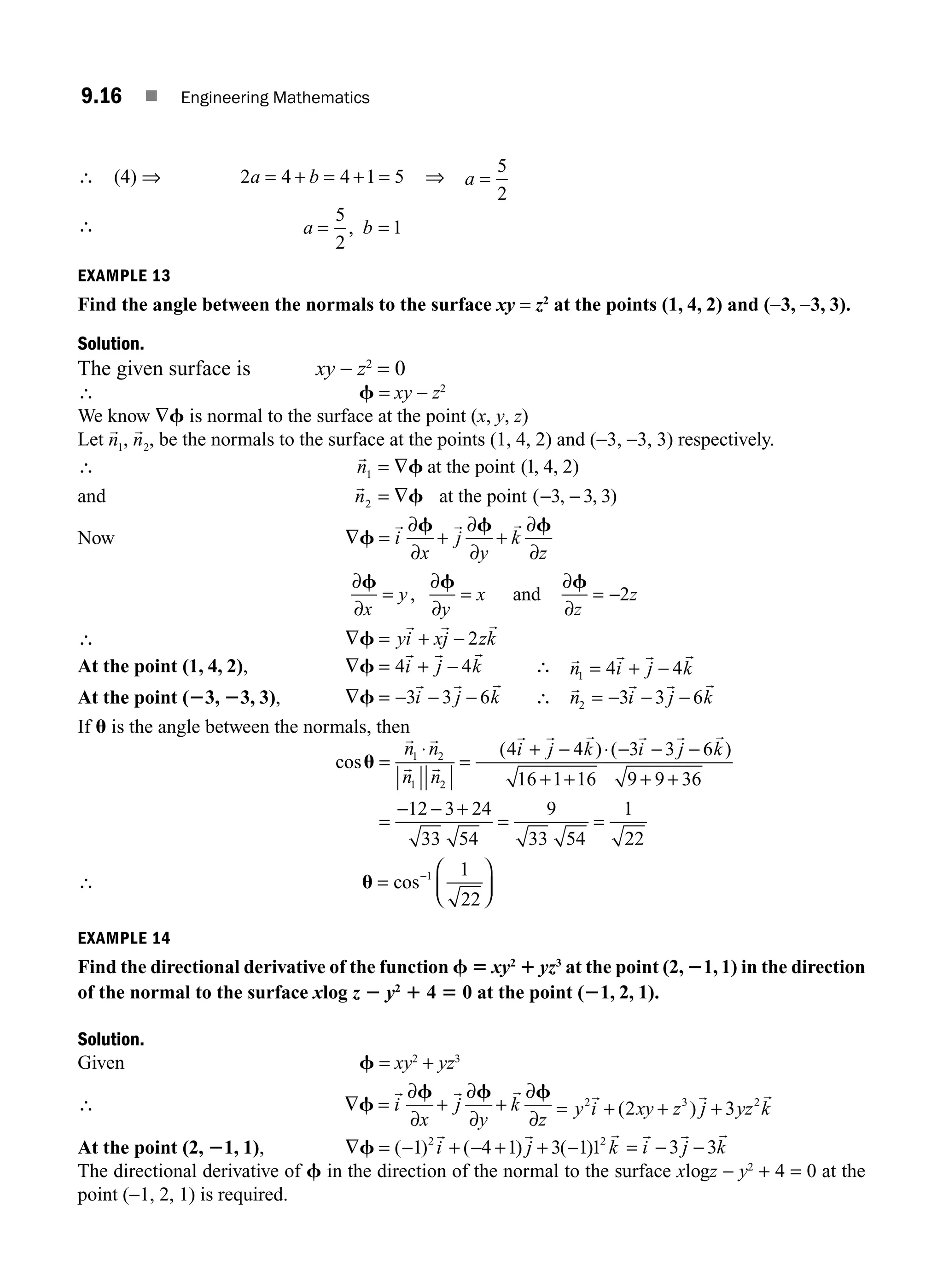

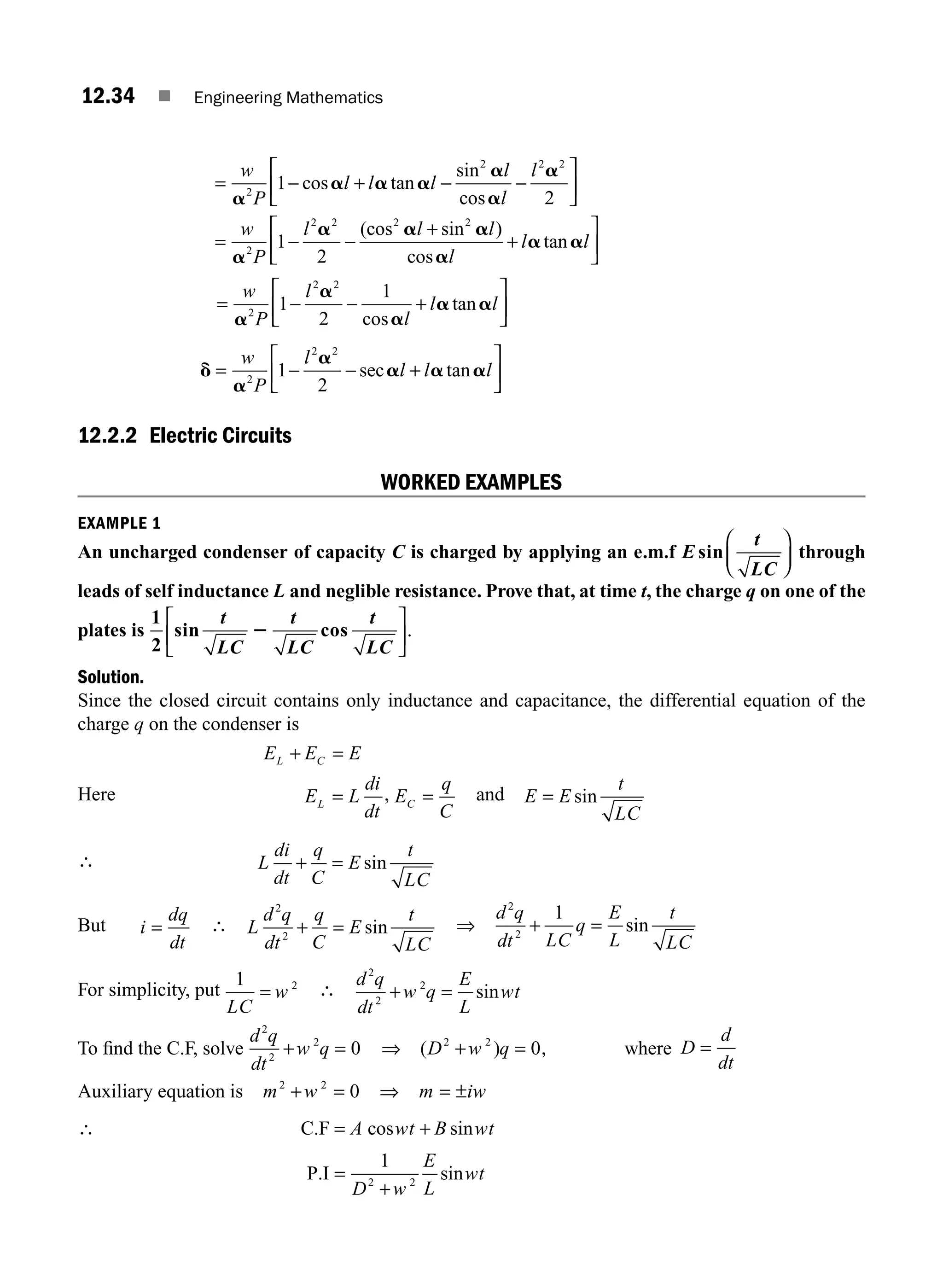

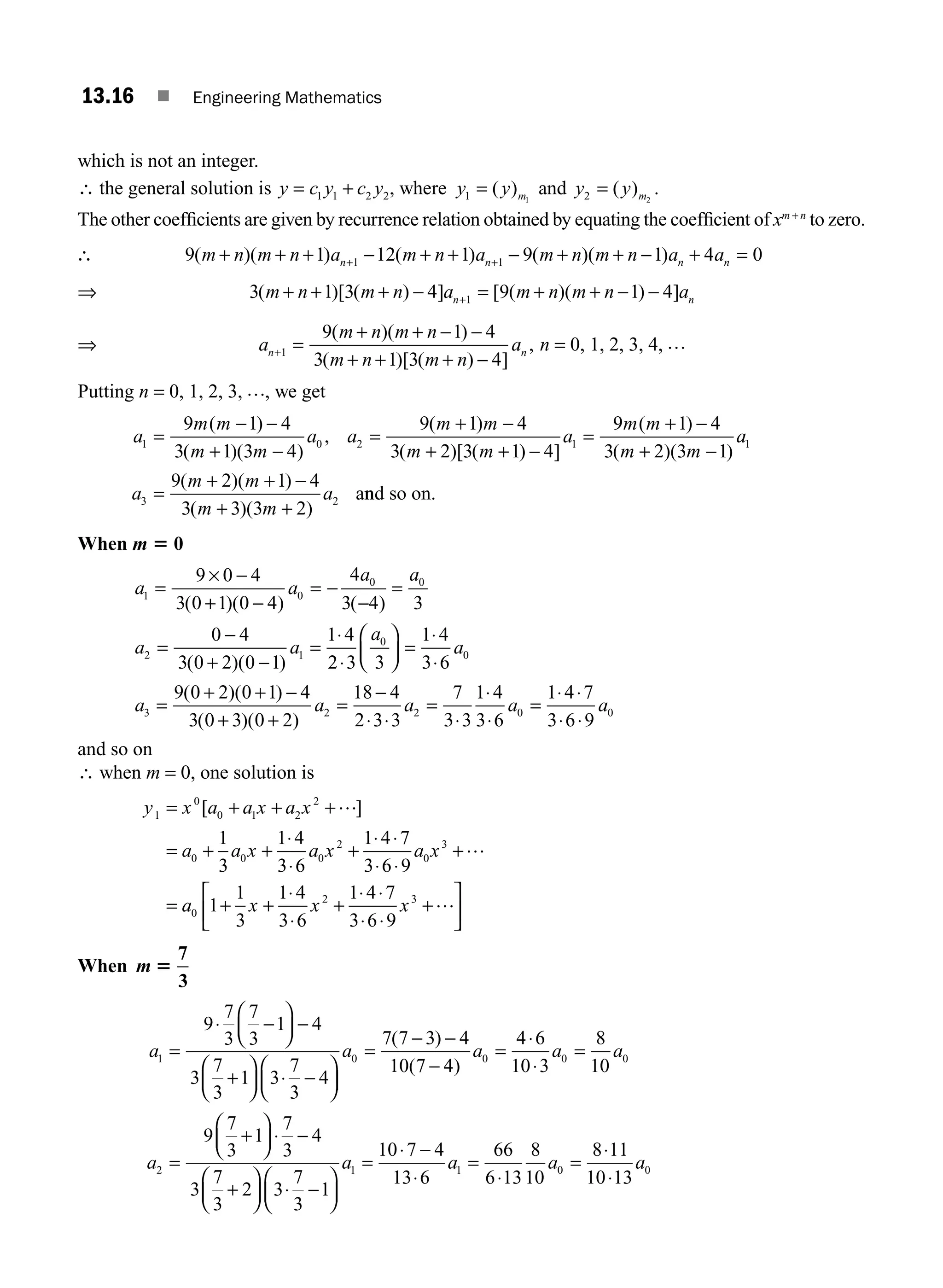

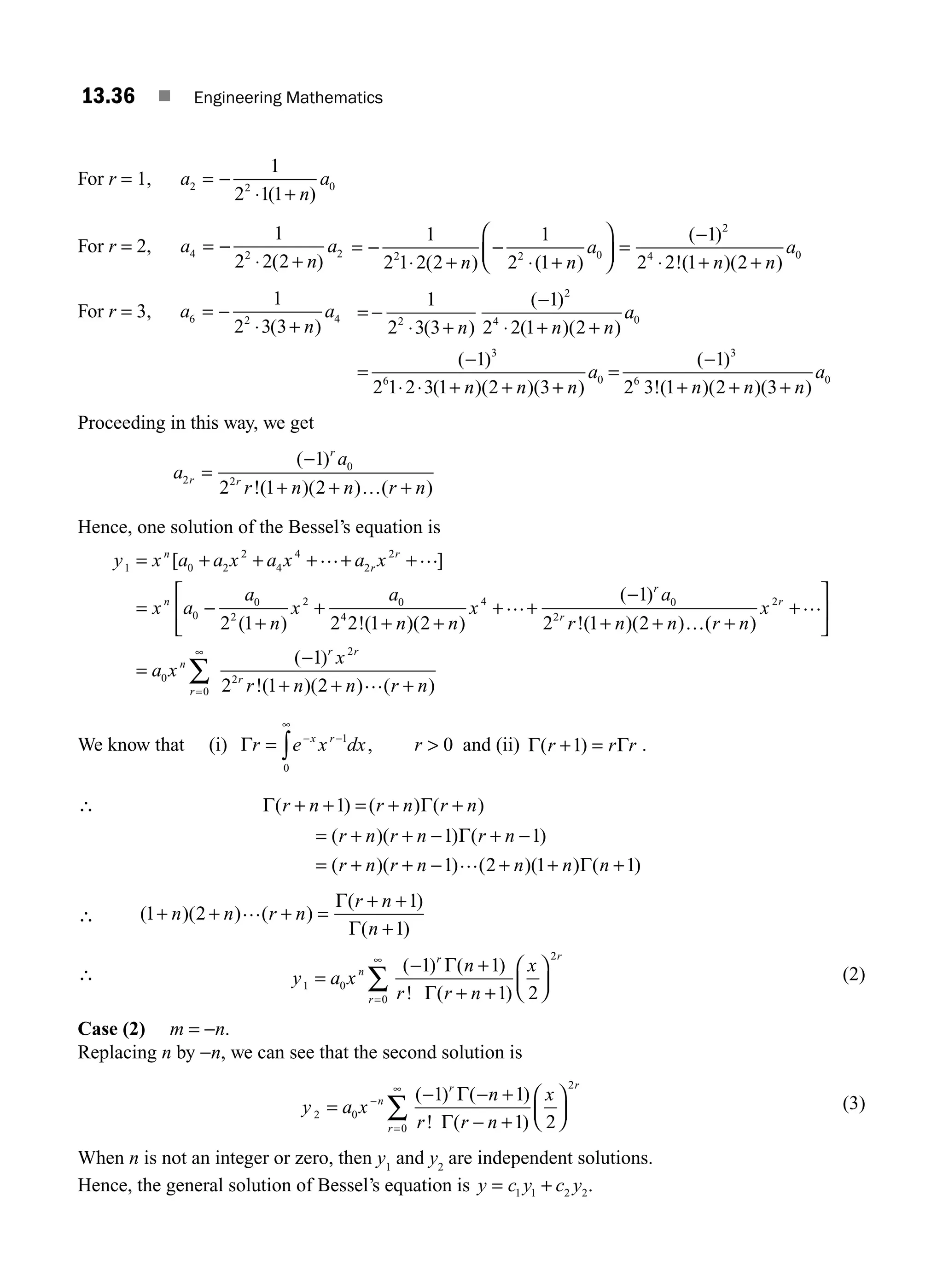

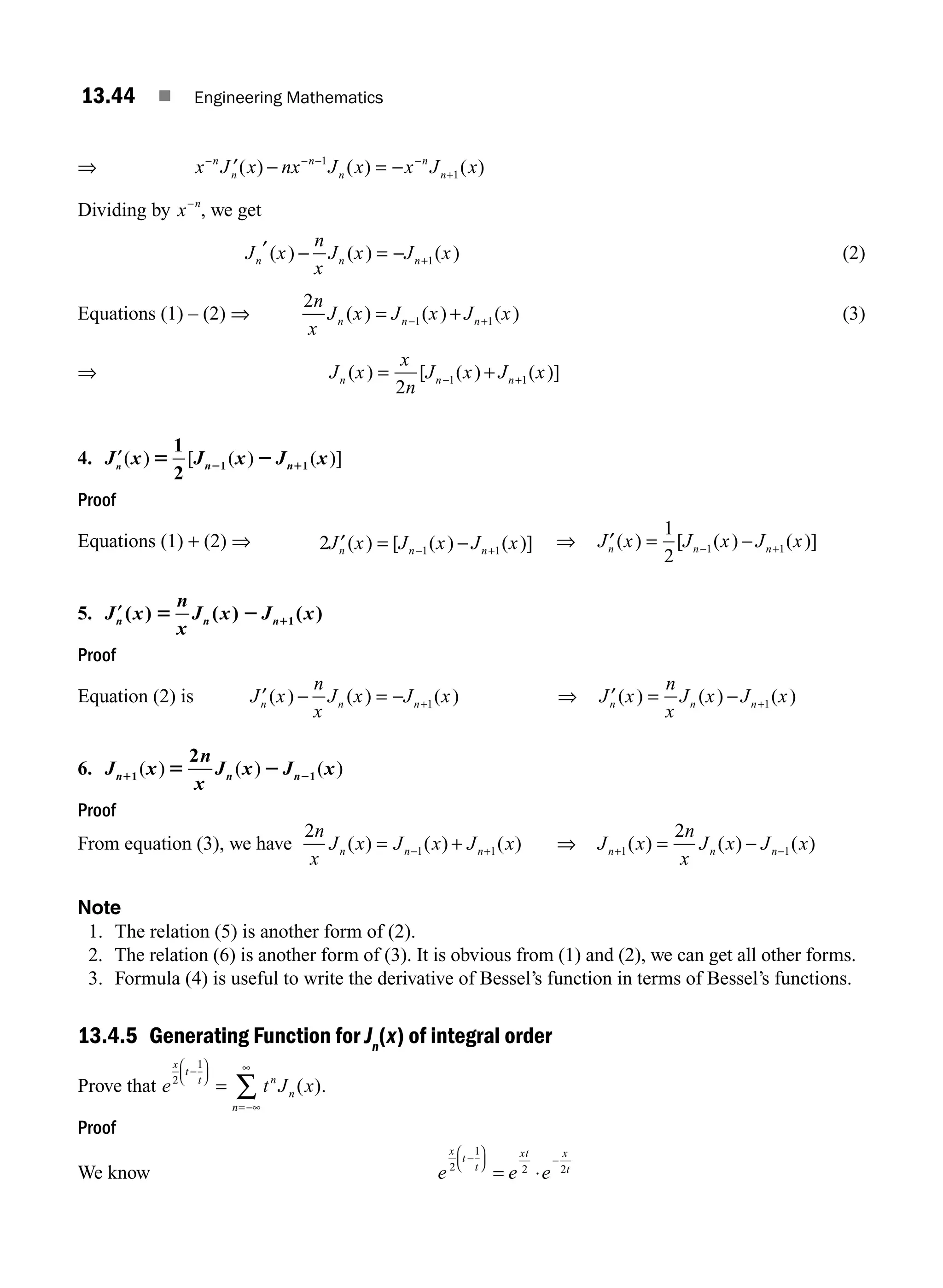

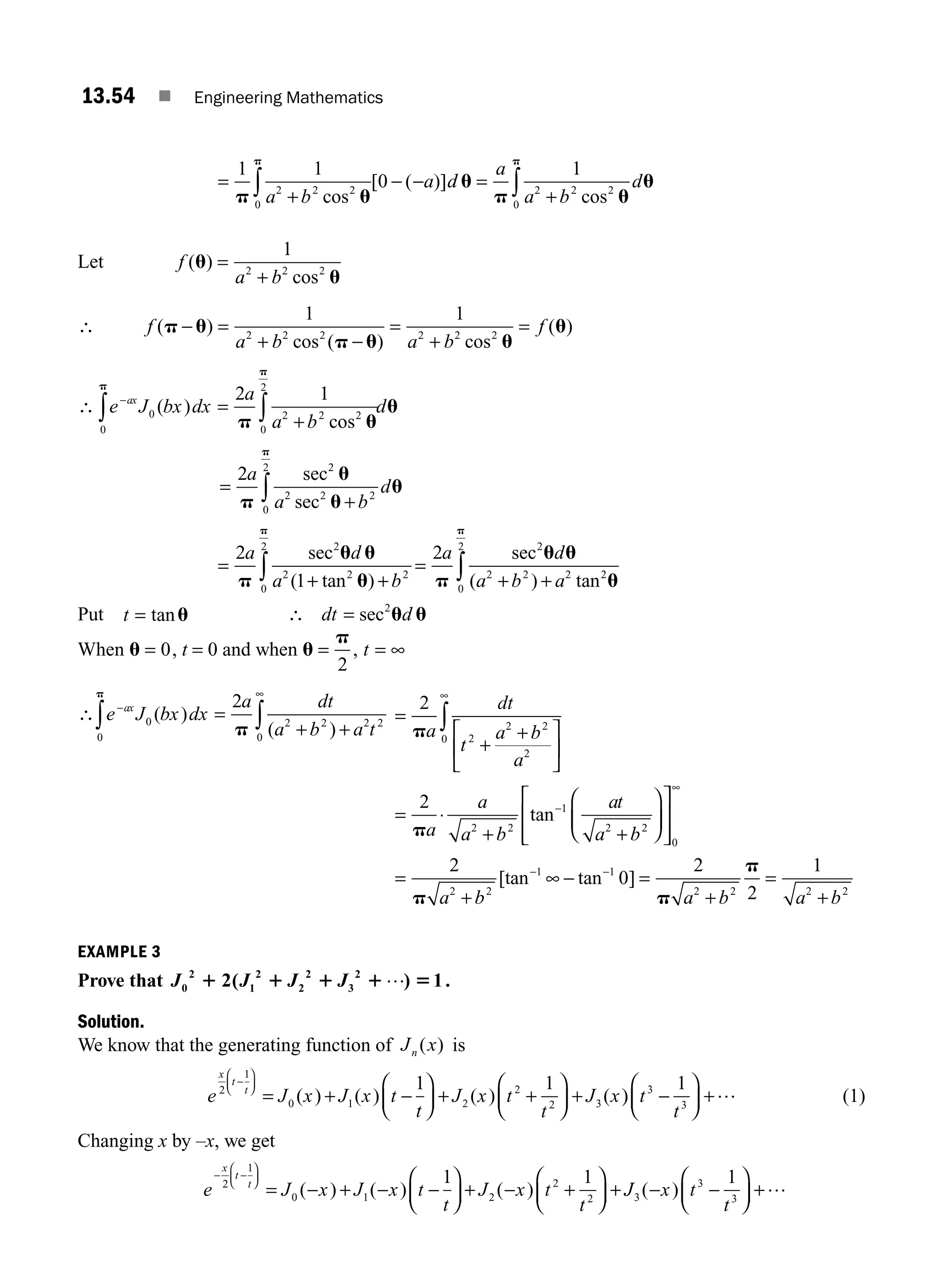

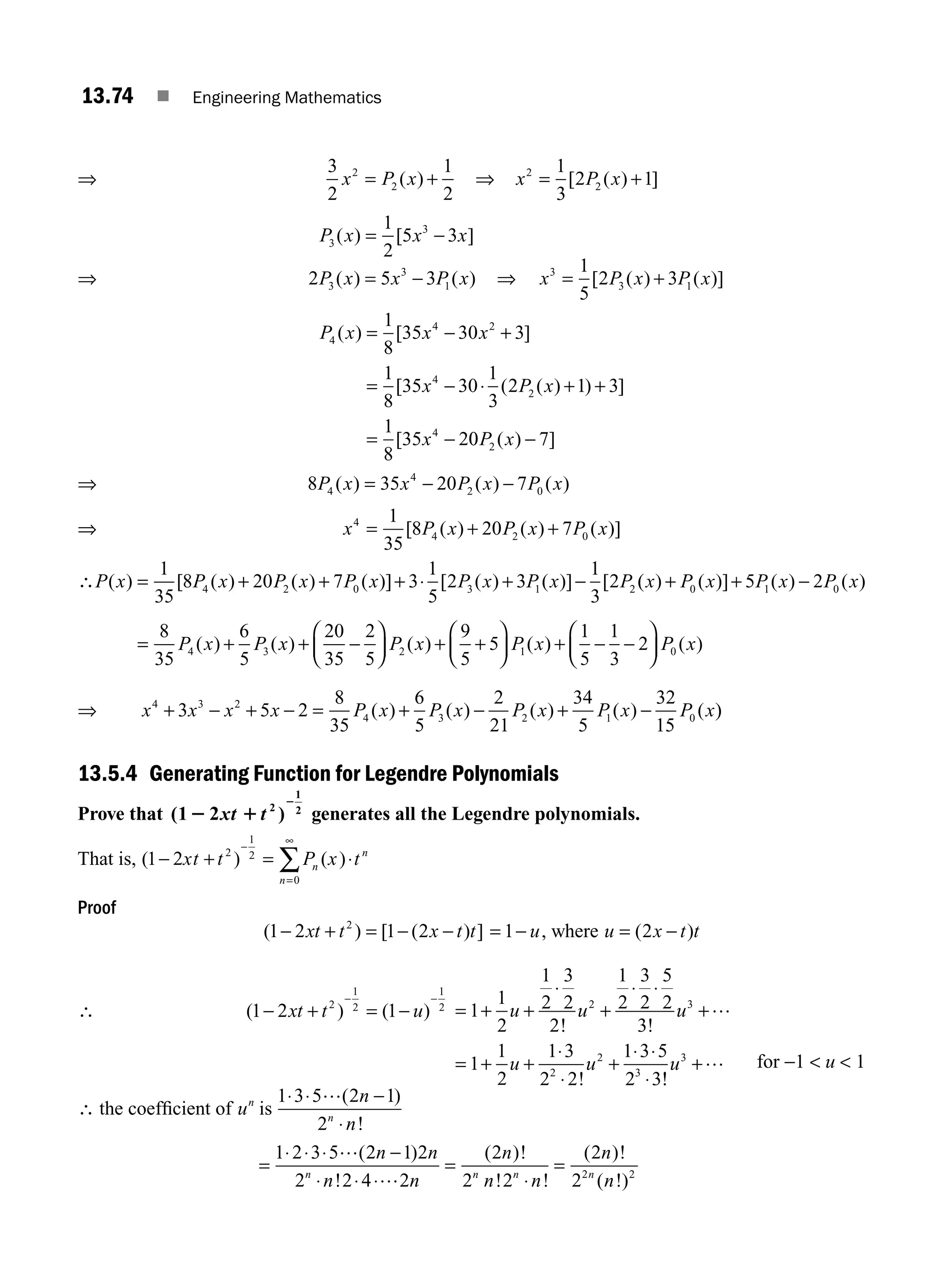

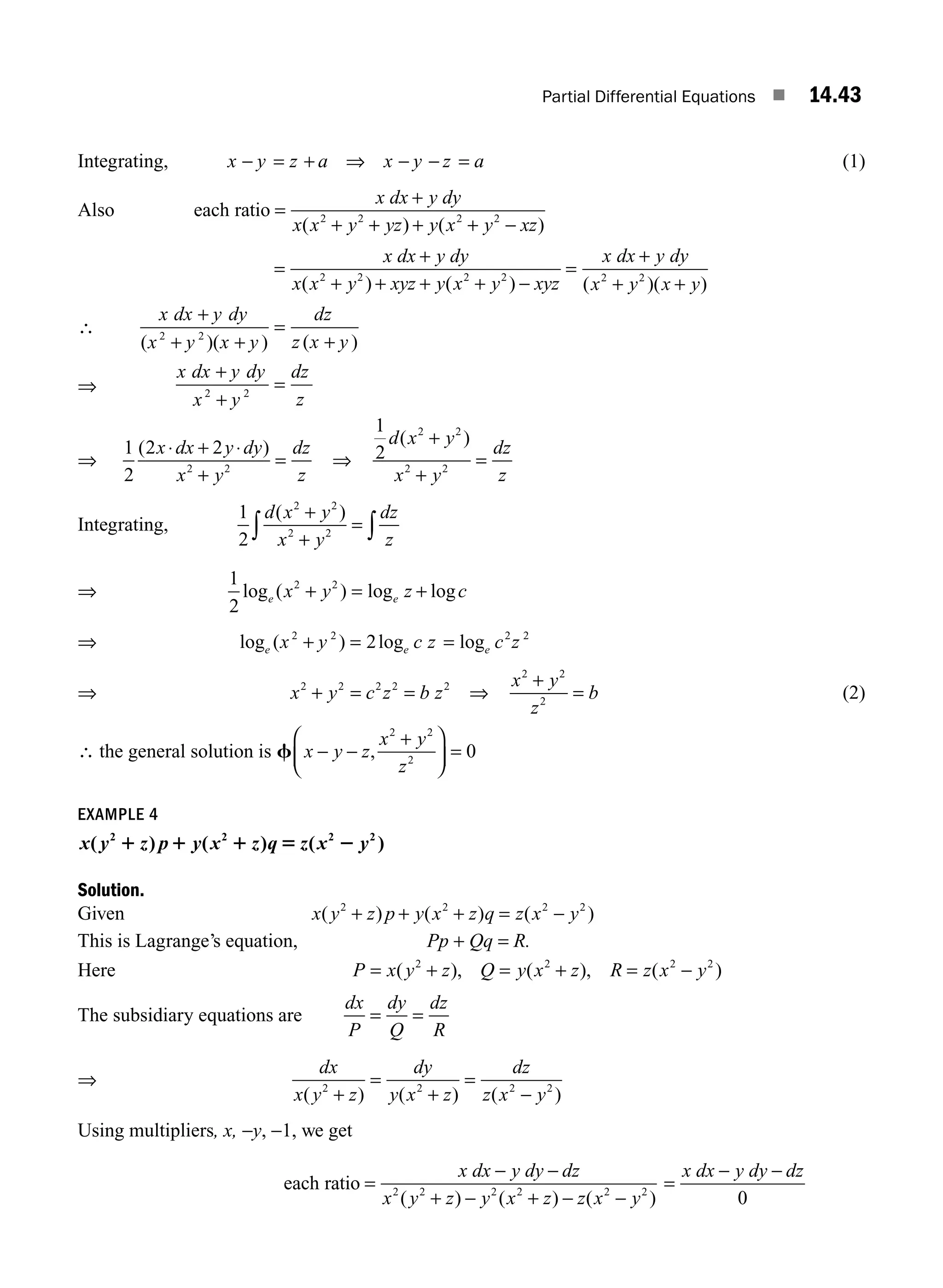

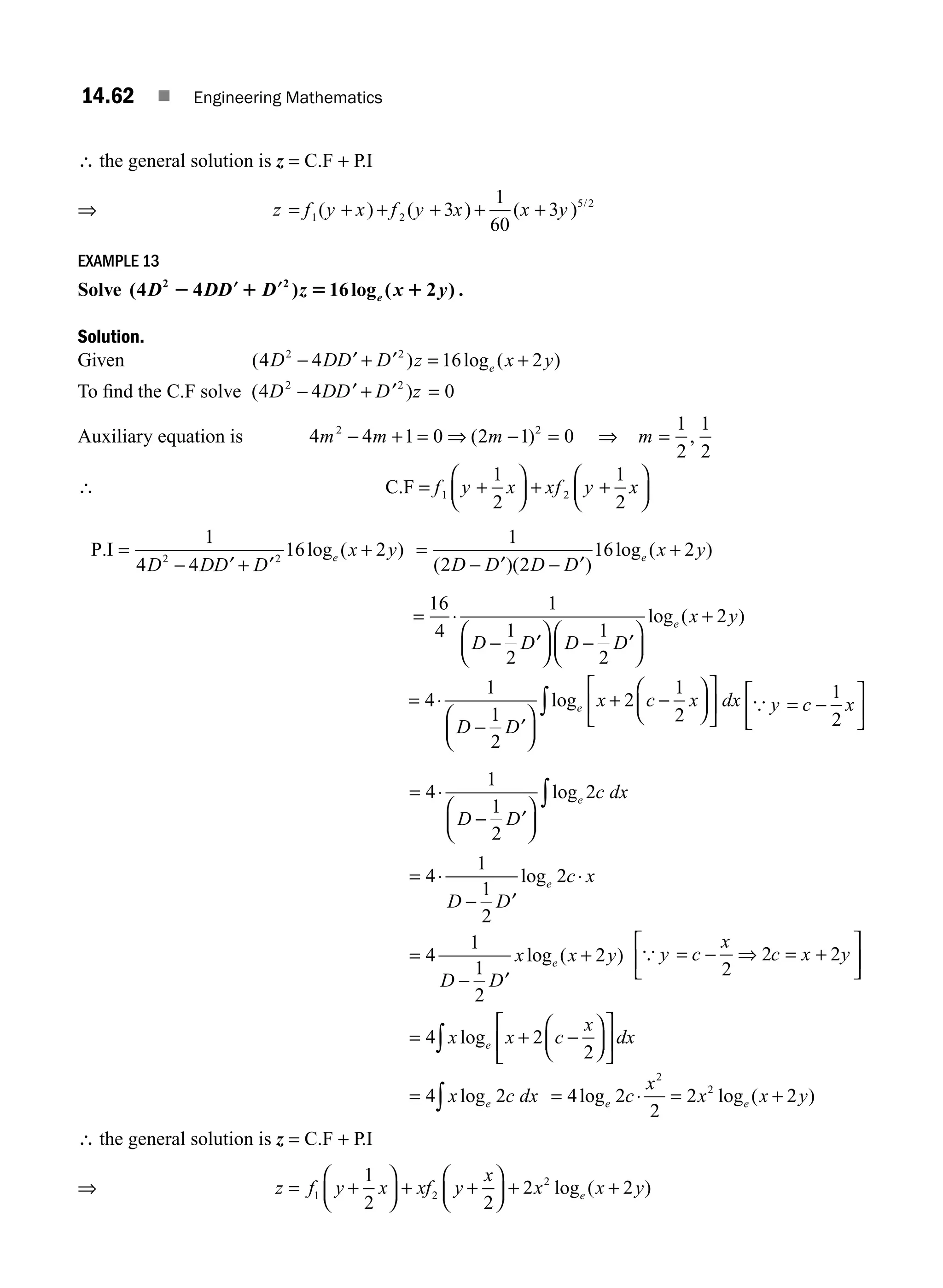

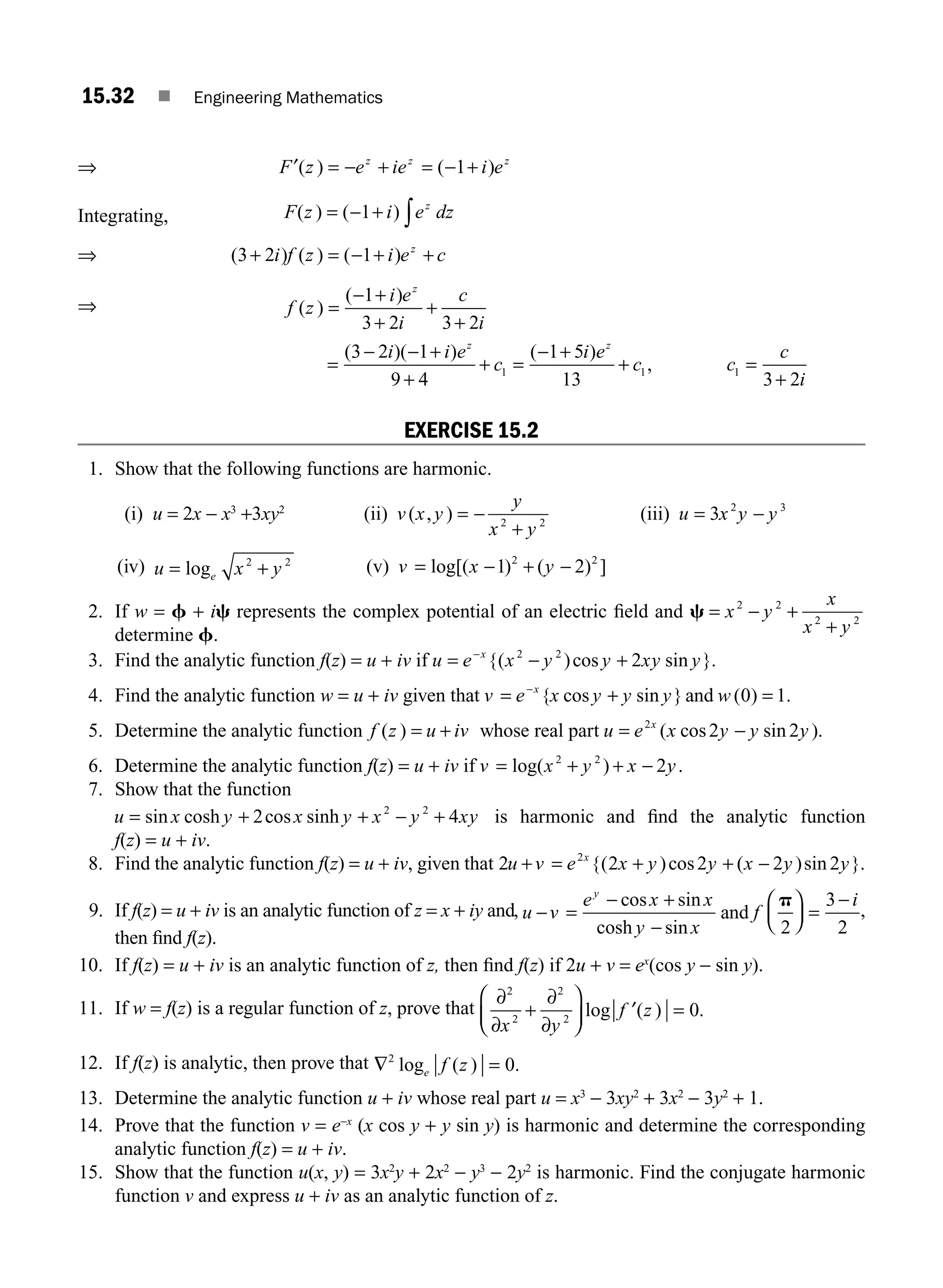

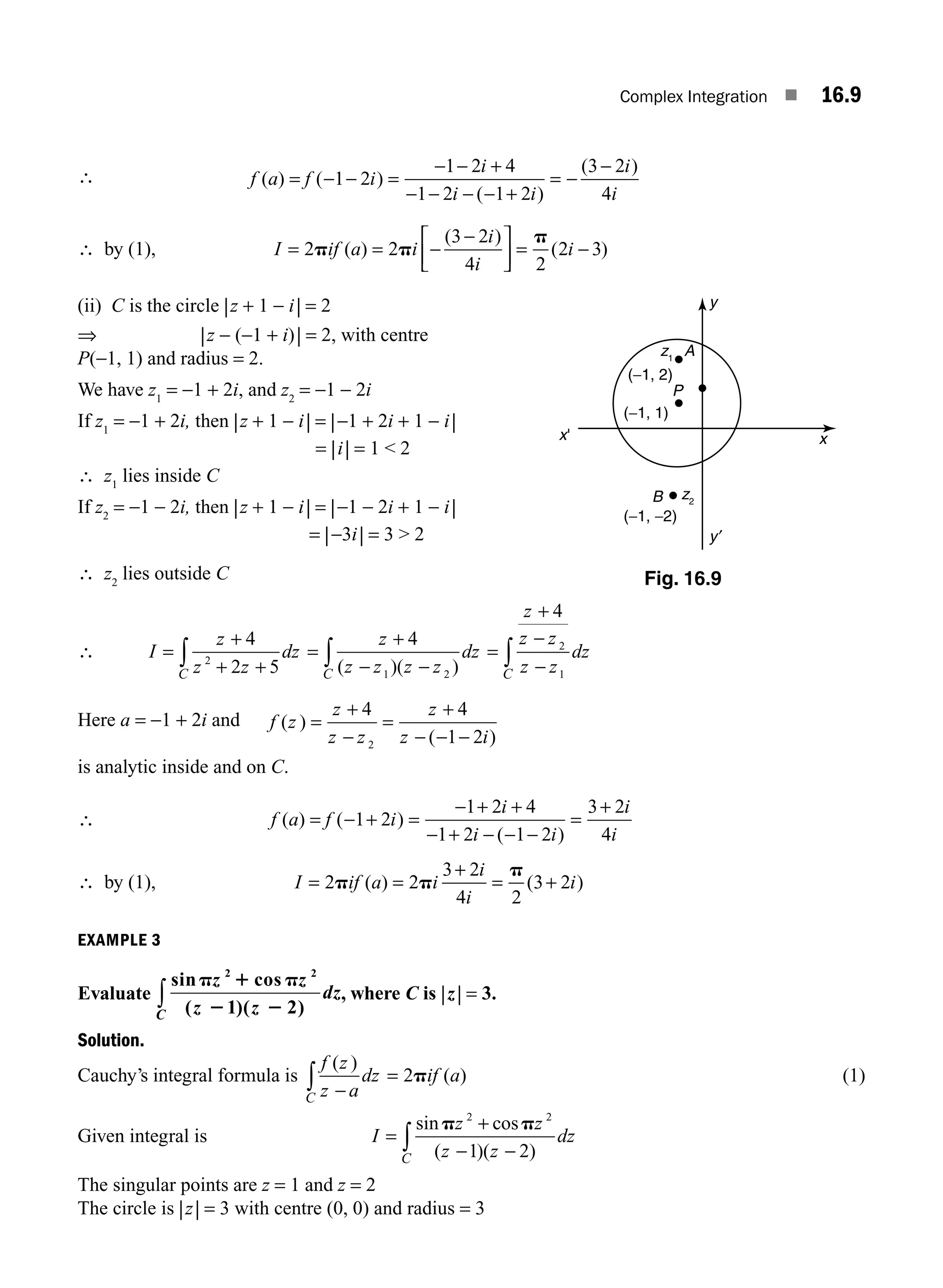

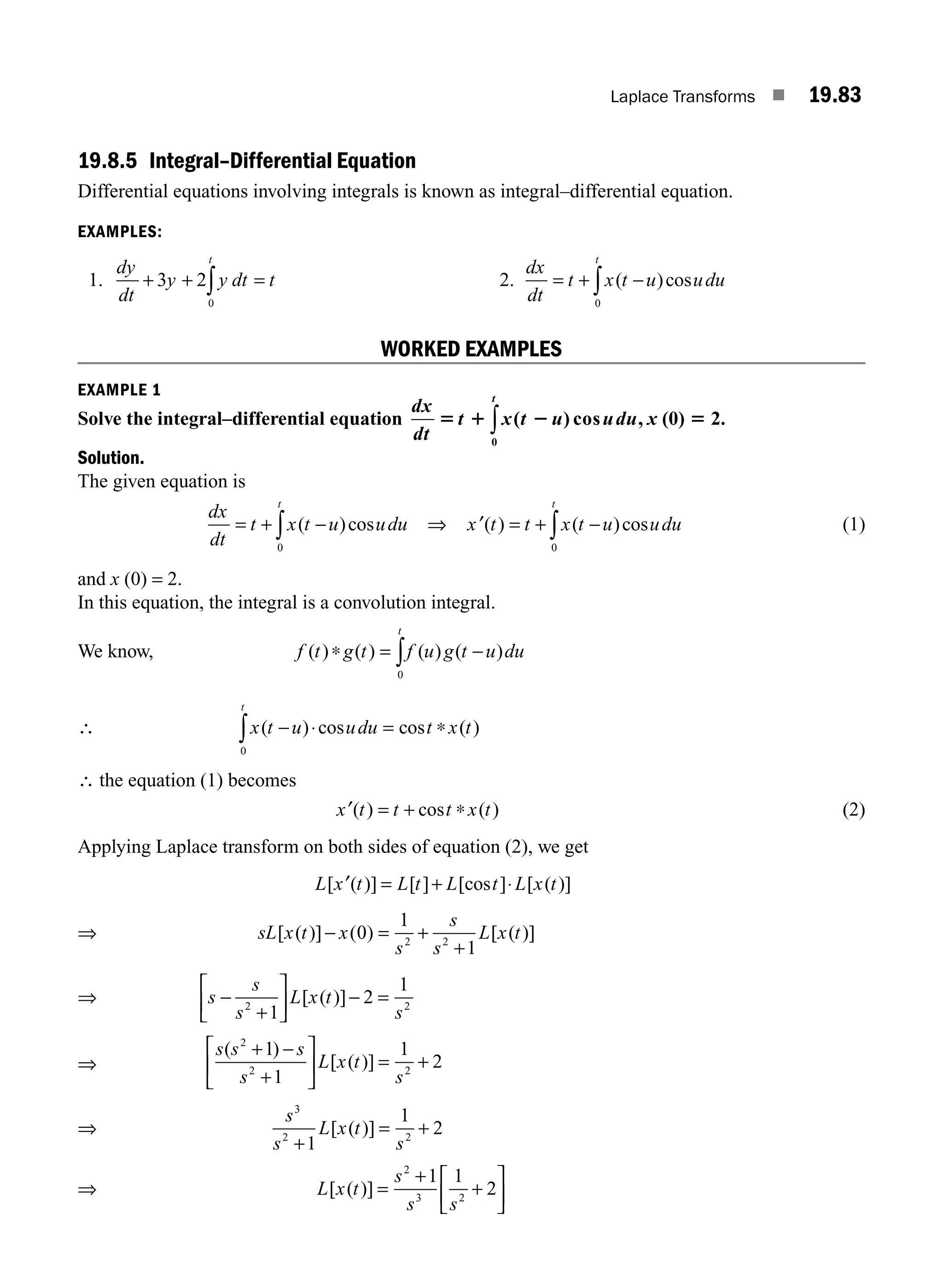

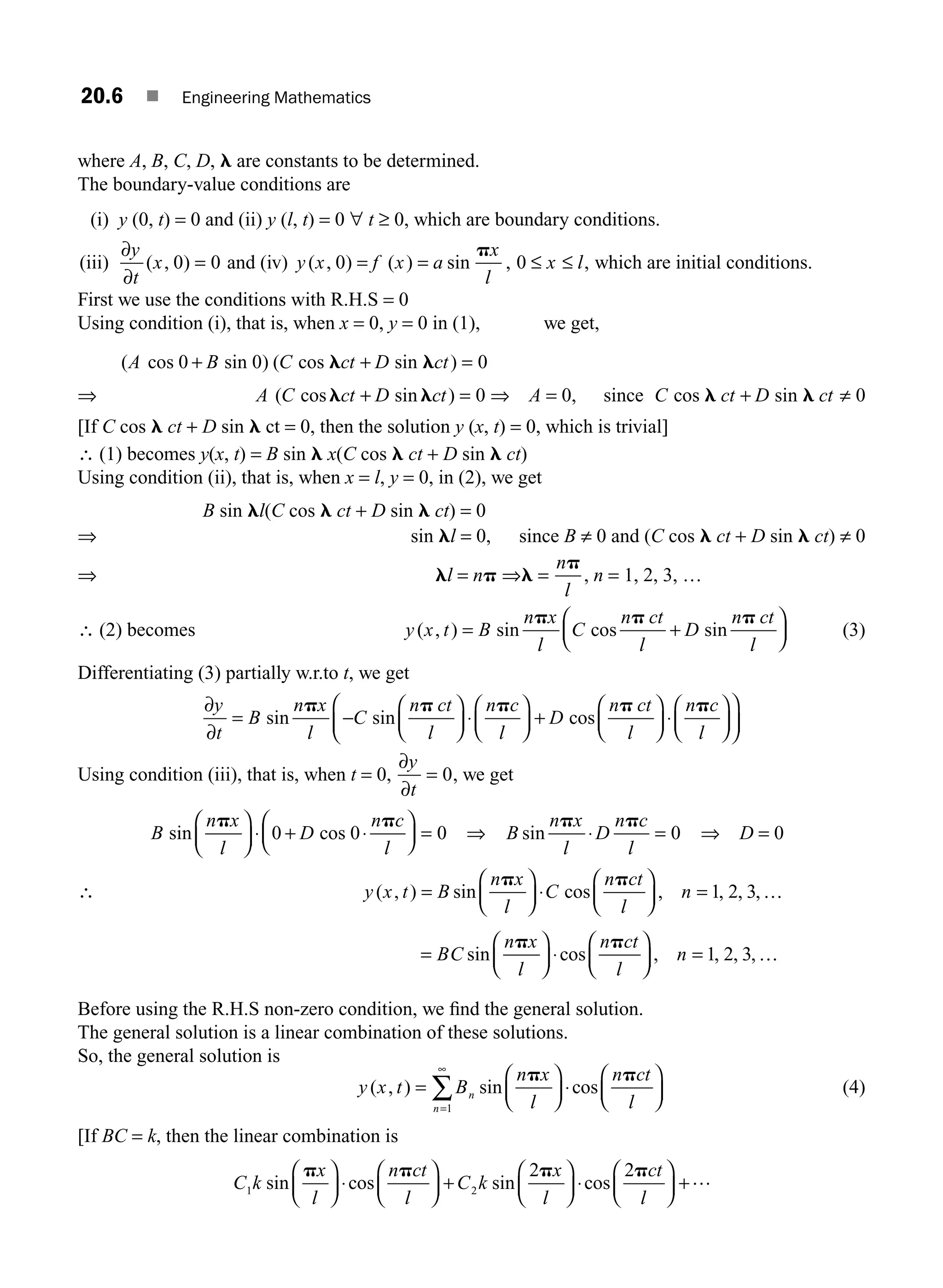

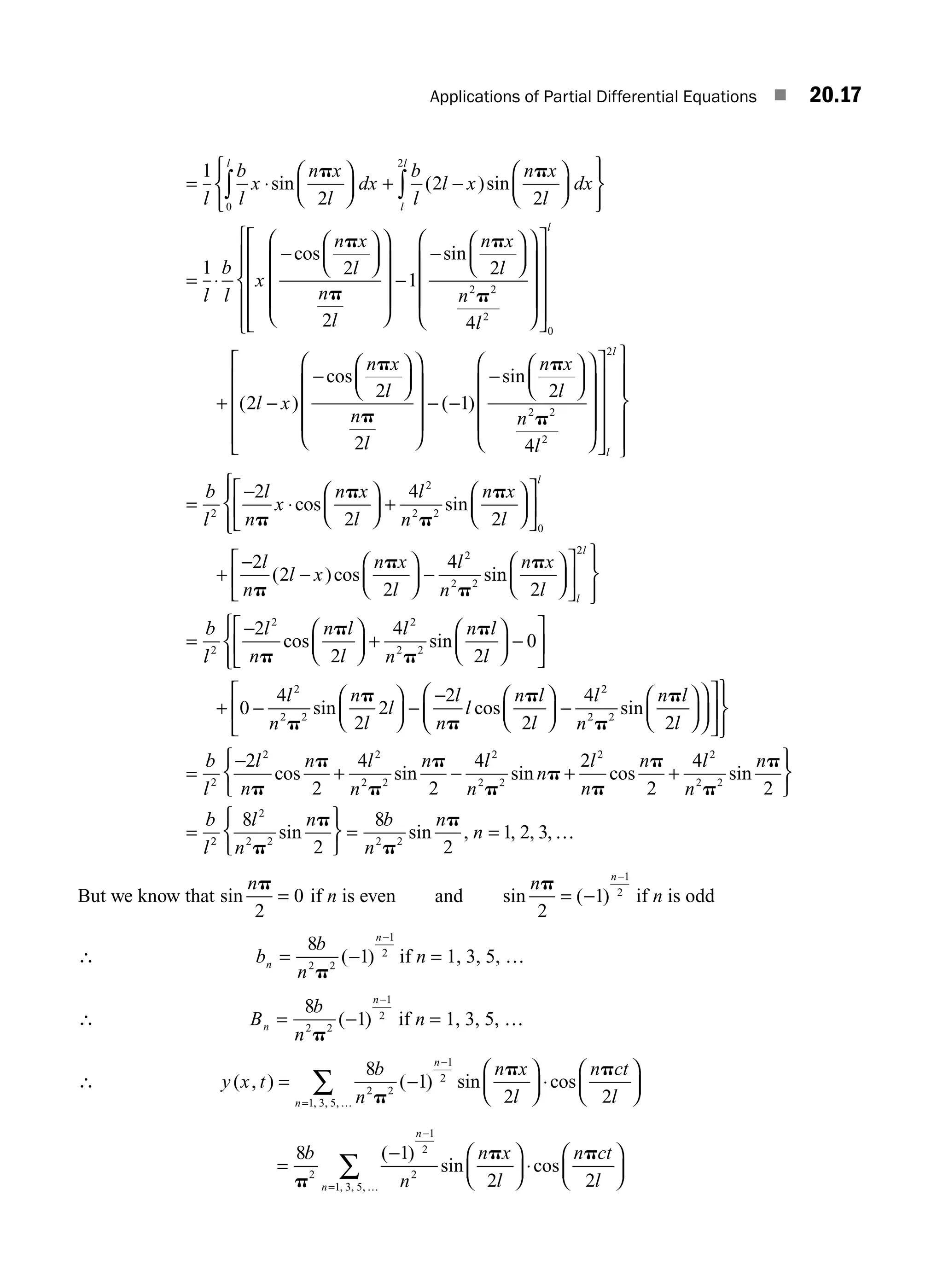

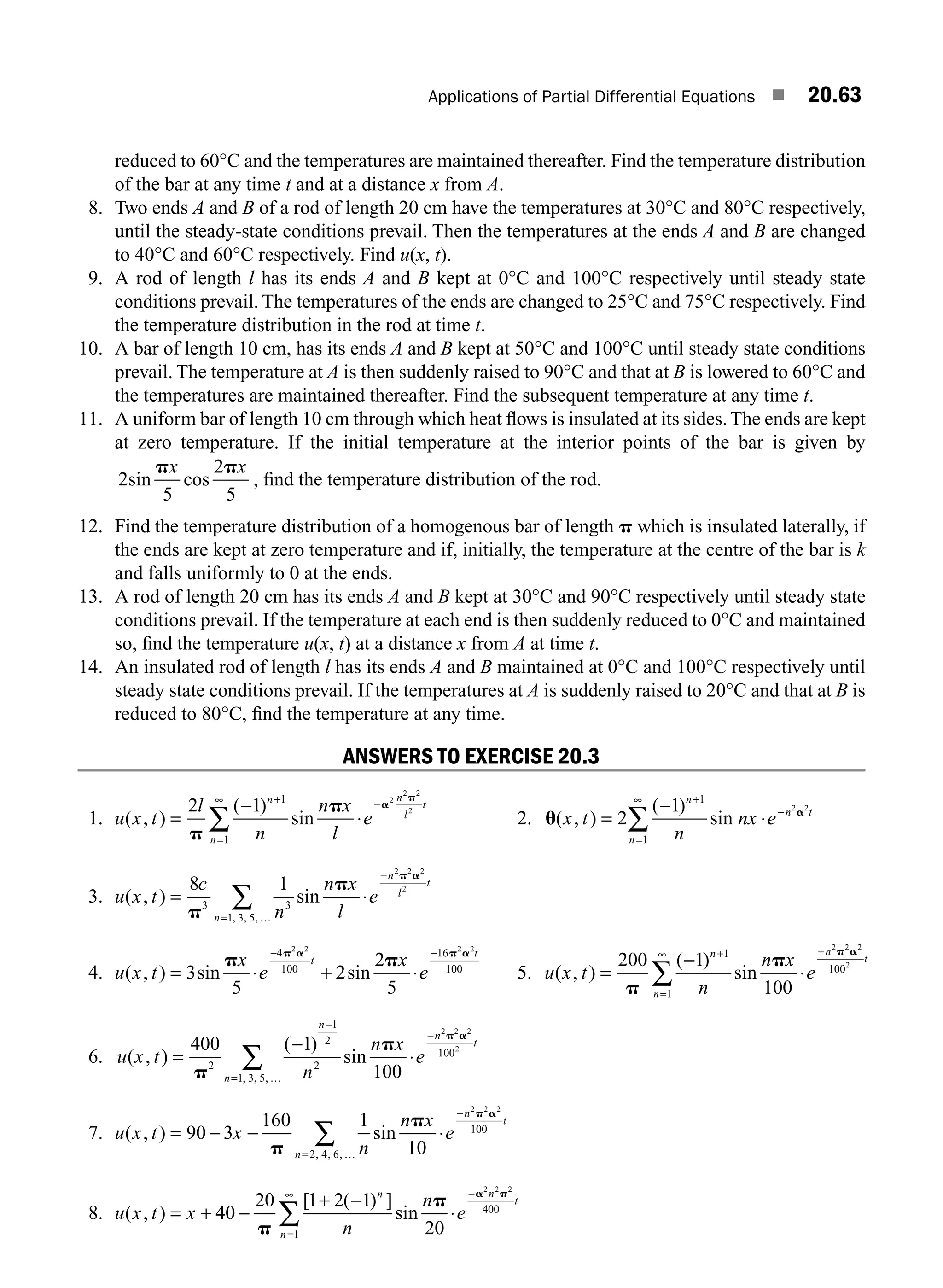

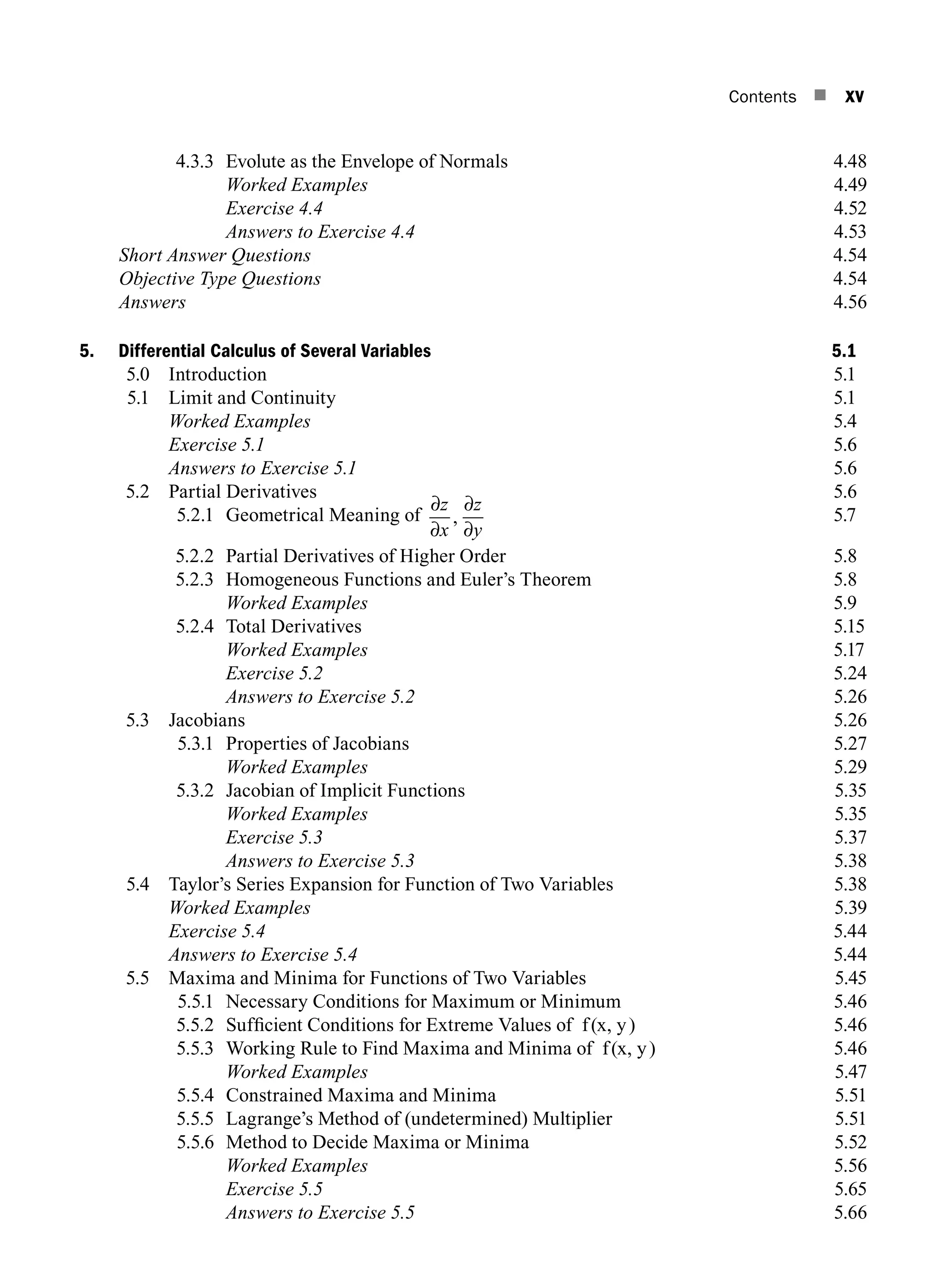

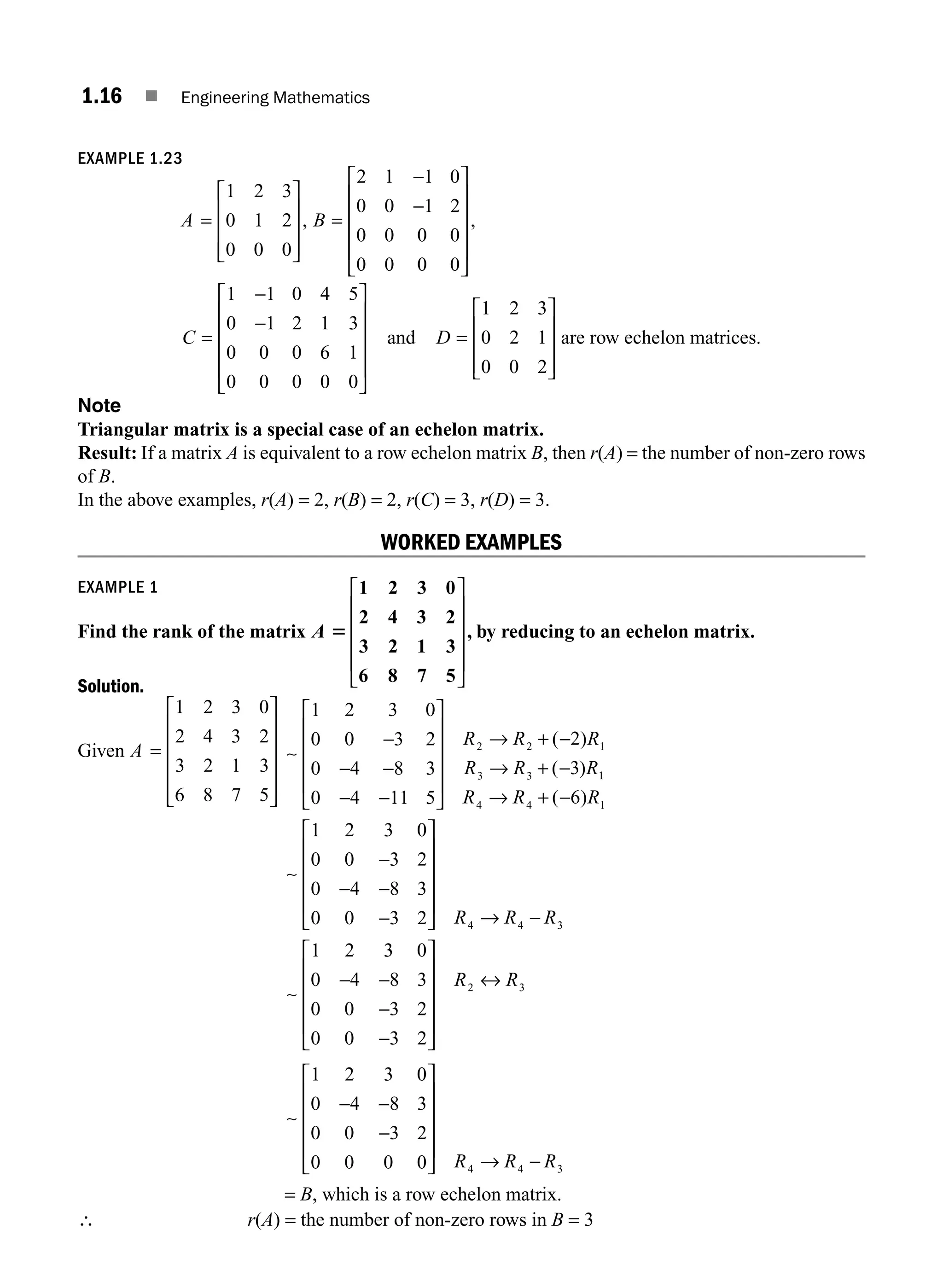

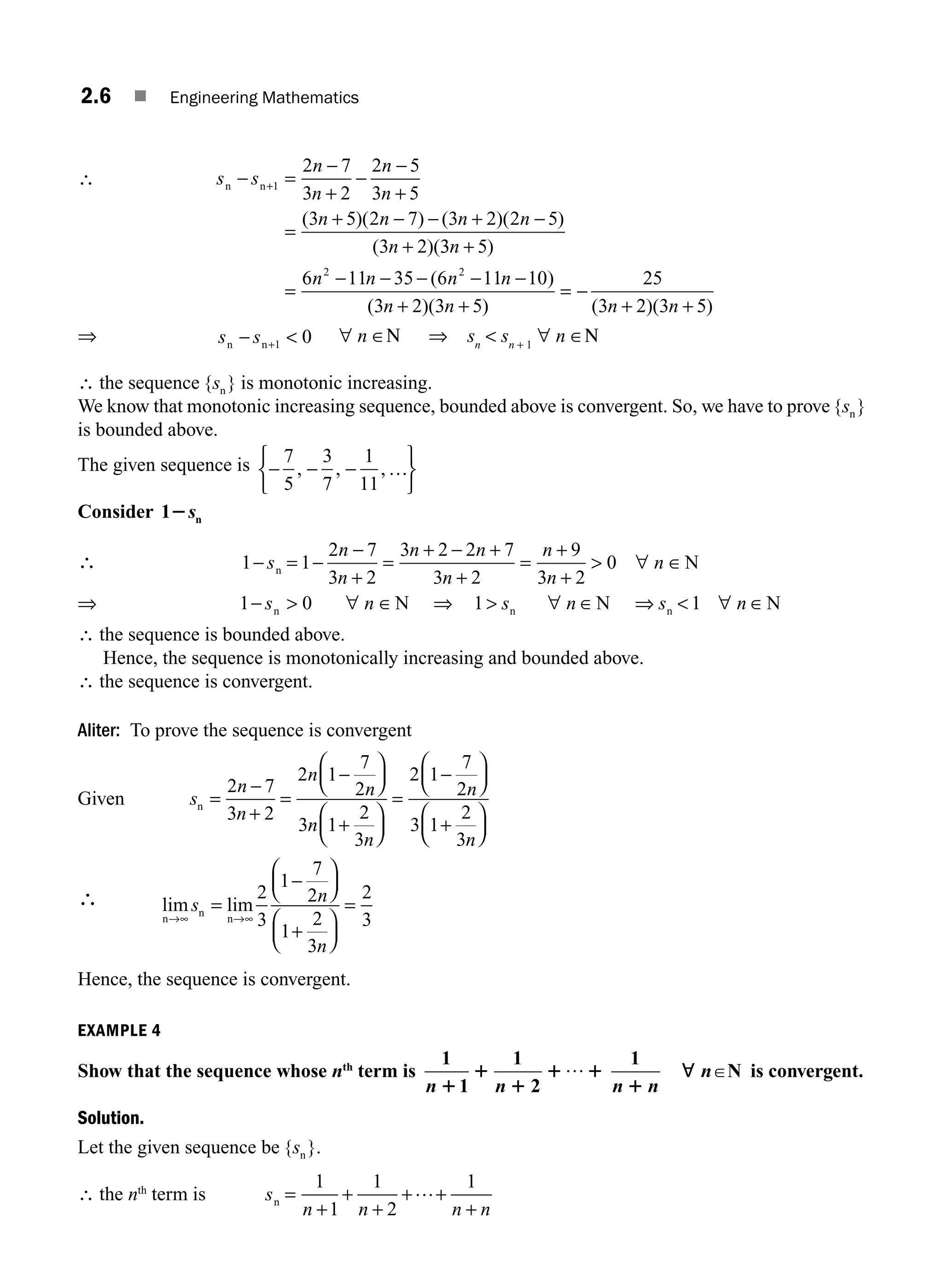

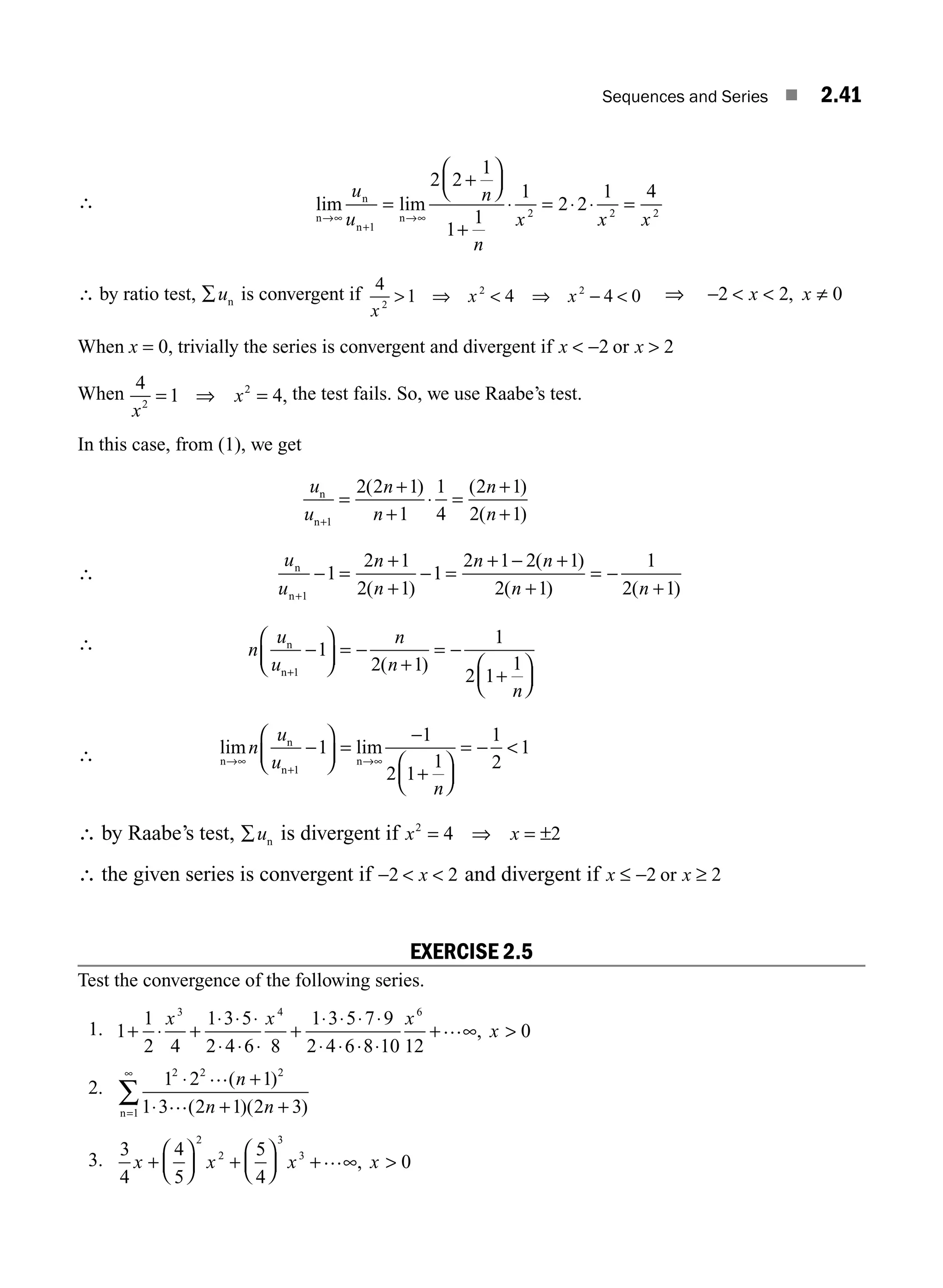

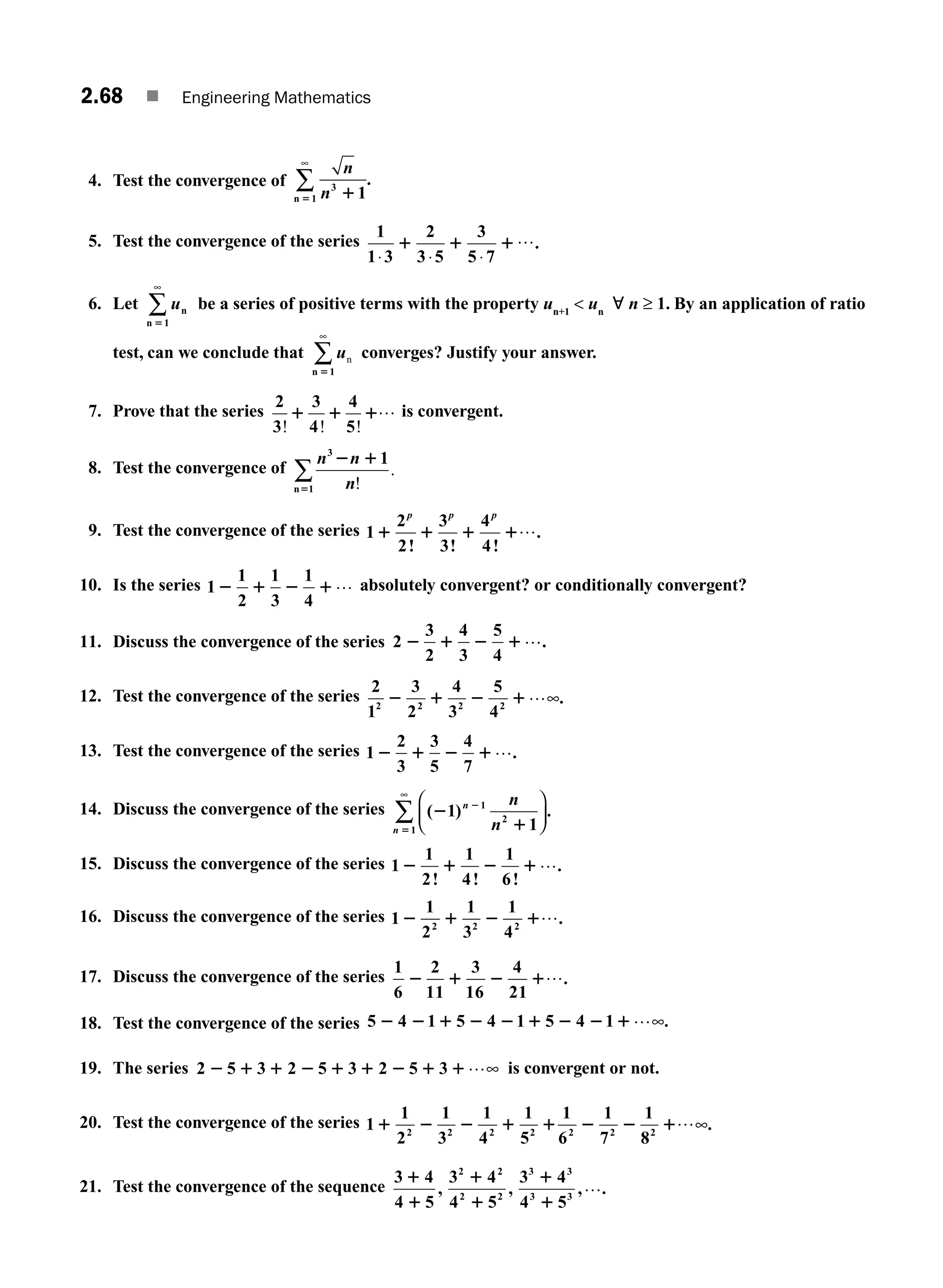

13.2 Frobenius Method 13.9

Worked Examples13.11

Exercise 13.213.33

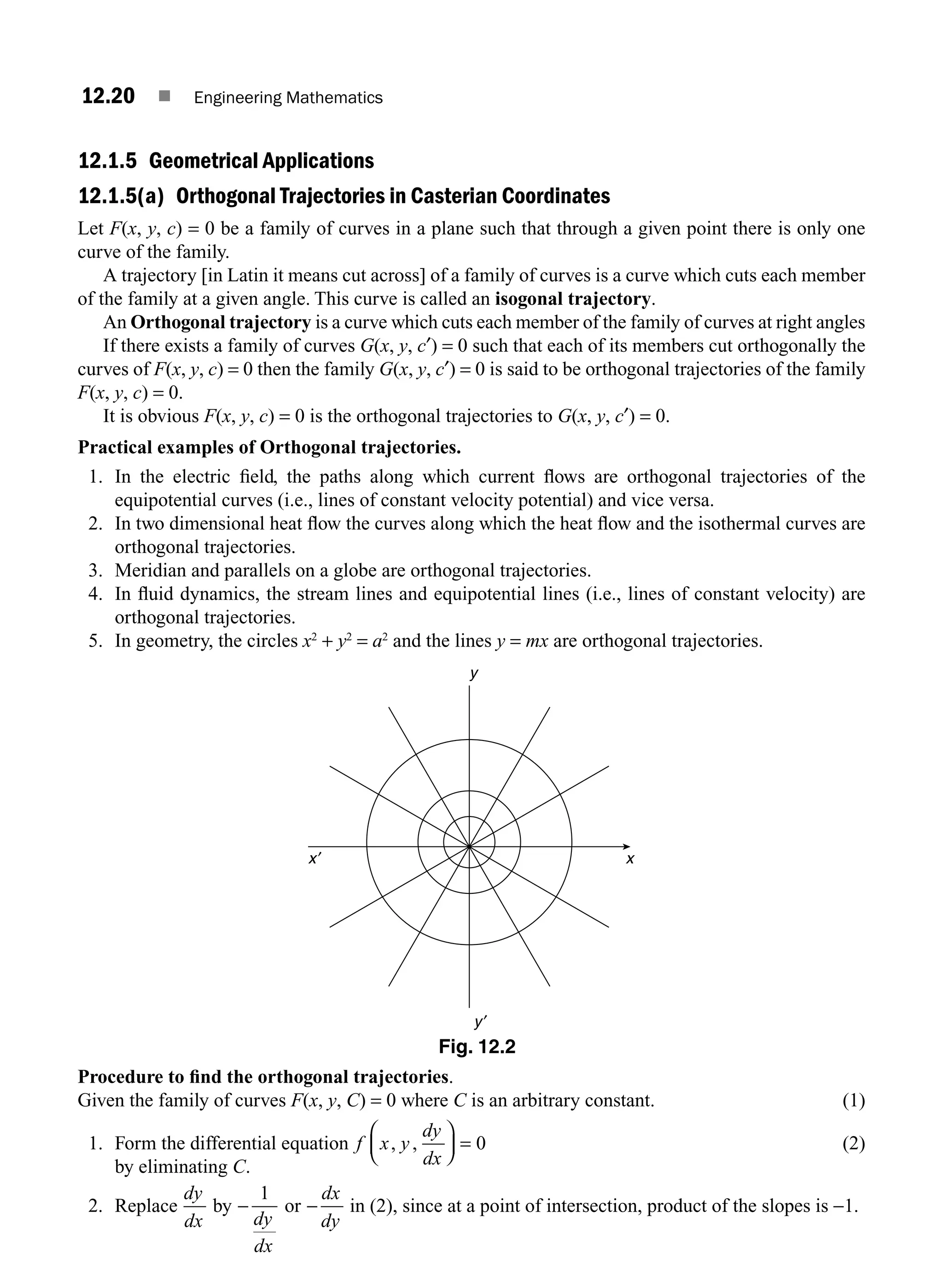

Answers to Exercise 13.213.33

13.3 Special Functions 13.34

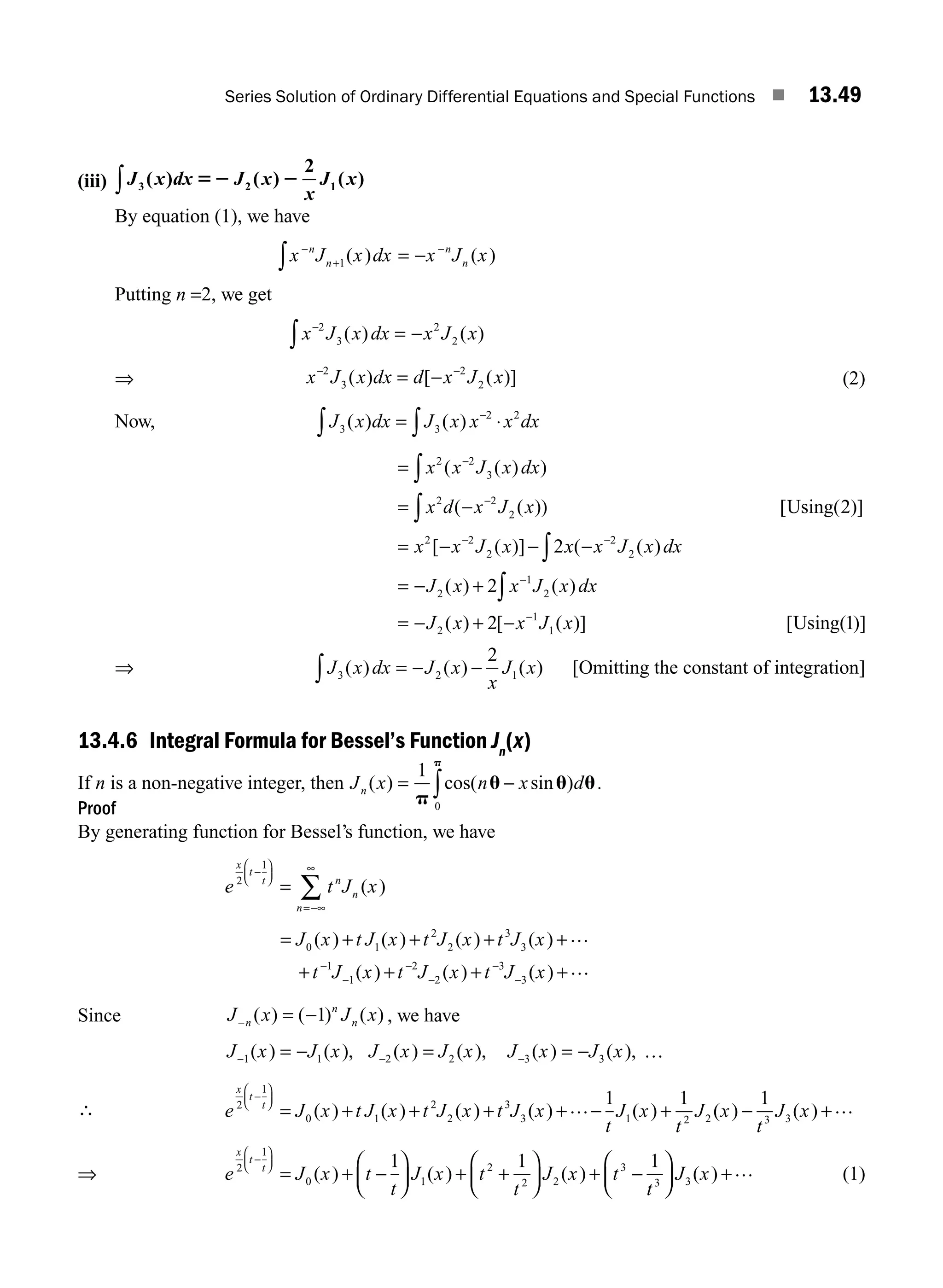

13.4 Bessel Functions 13.34

13.4.1 Series Solution of Bessel’s Equation 13.34

13.4.2 Bessel’s Functions of the First Kind 13.37

Worked Examples13.39

13.4.3 Some Special Series 13.40

13.4.4 Recurrence Formula for Jn (x)13.41

13.4.5 Generating Function for Jn (x) of Integral Order 13.44

Worked Examples13.46

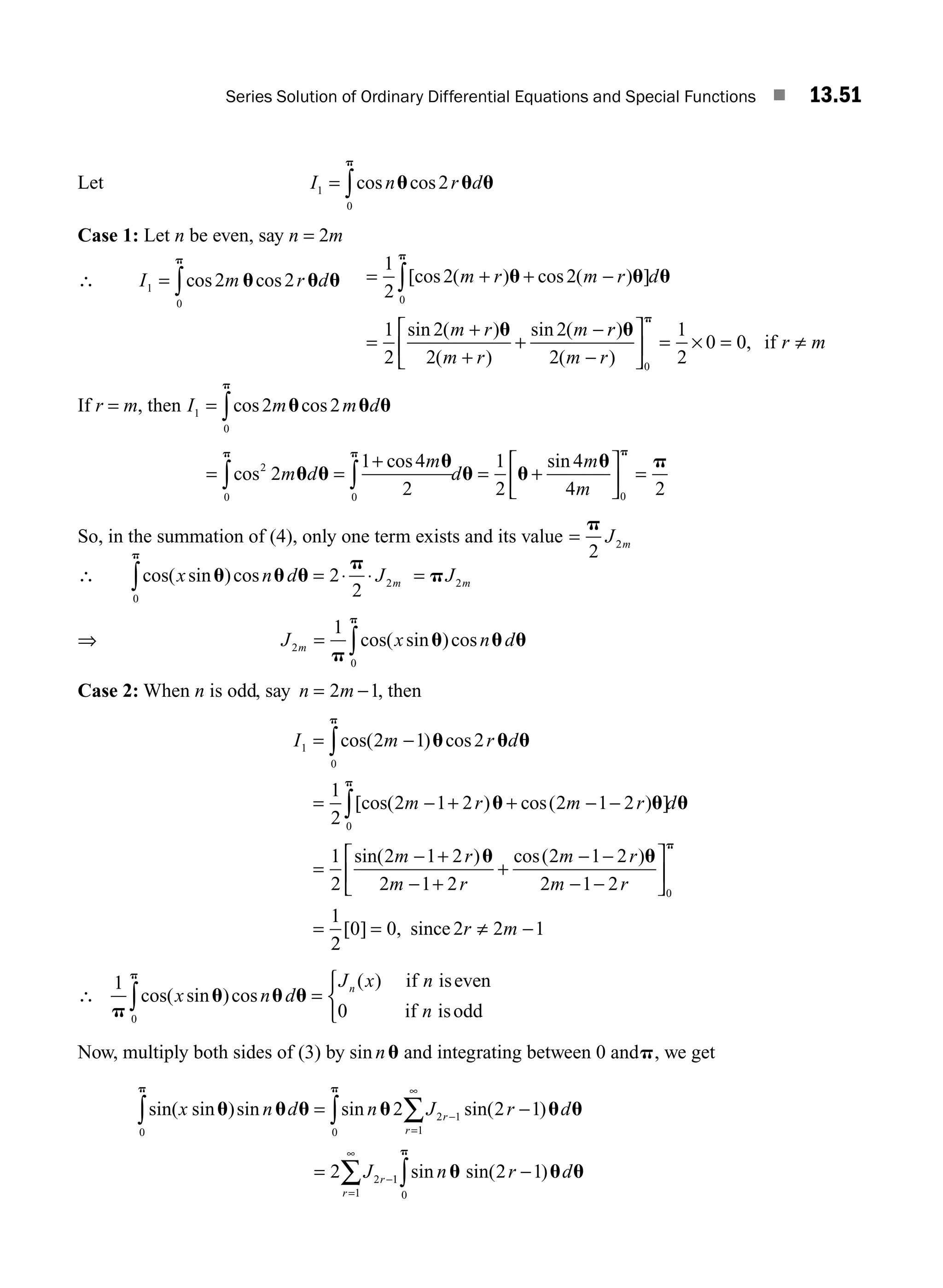

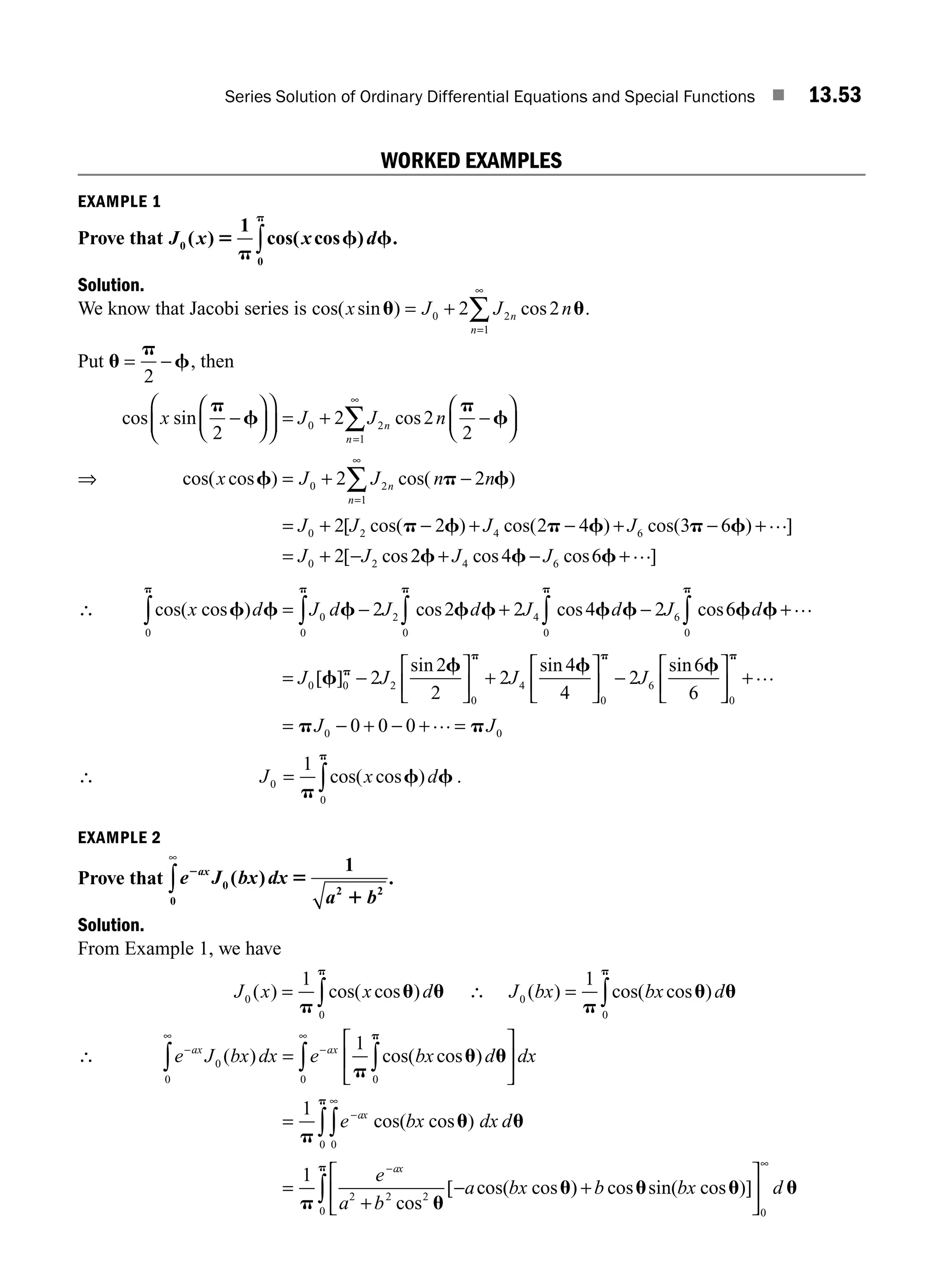

13.4.6 Integral Formula for Bessel’s Function Jn (x) 13.49

Worked Examples13.53

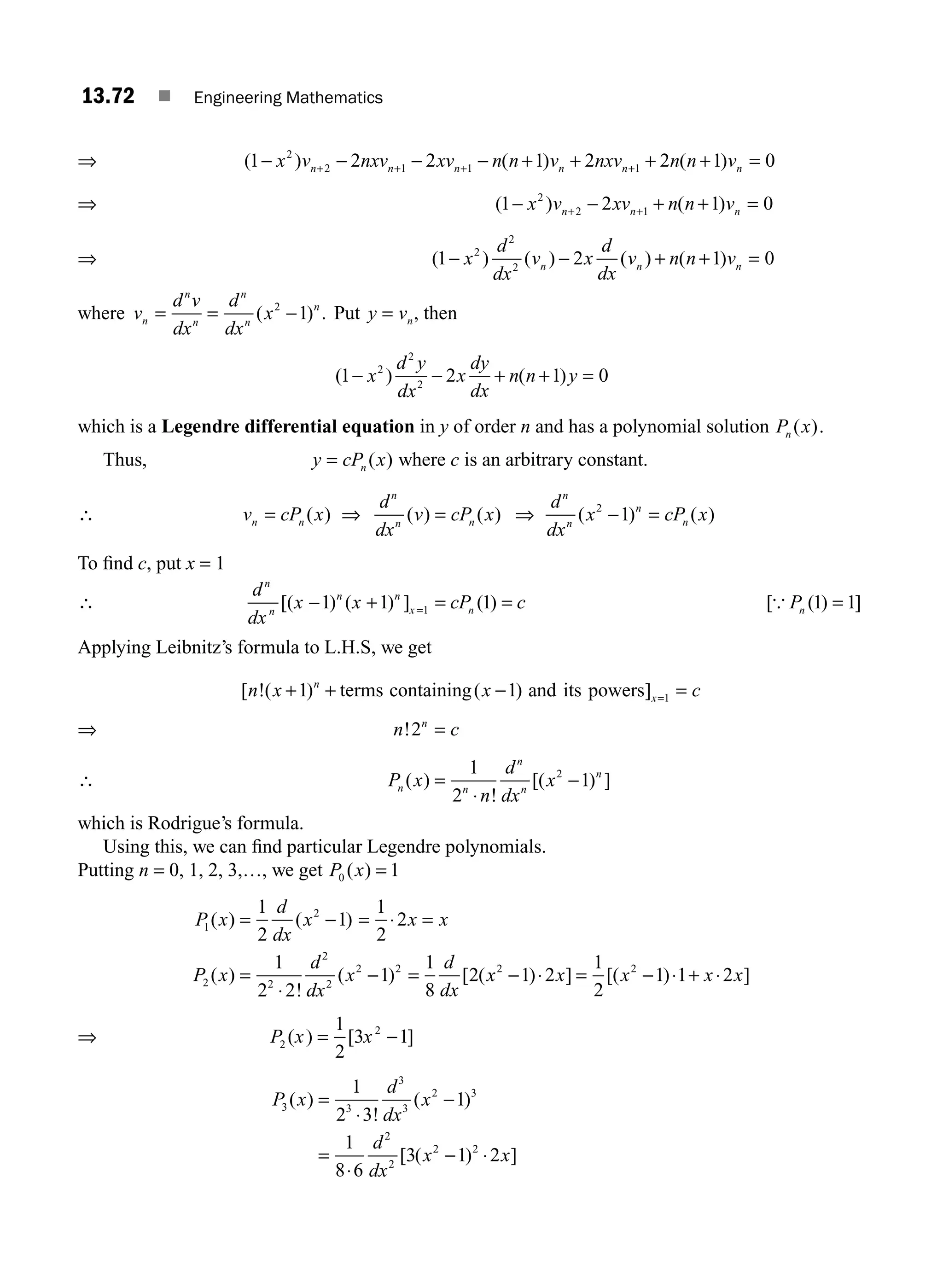

13.4.7 Orthogonality of Bessel’s Functions 13.56

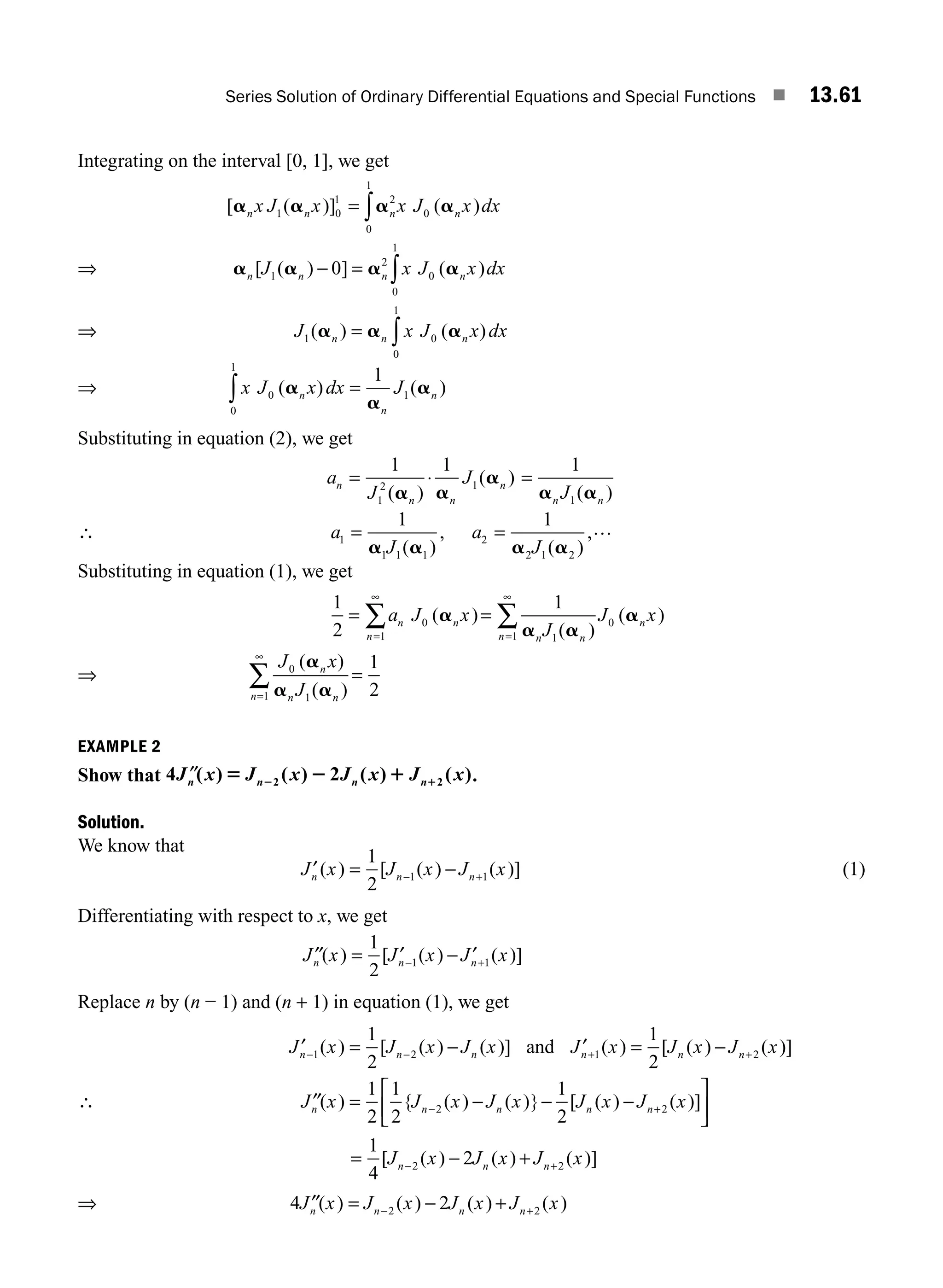

13.4.8 Fourier–Bessel Expansion of a Function f(x)13.59

Worked Examples13.60

13.4.9 Equations Reducible to Bessel’s Equation 13.62

Worked Examples13.62

Exercise 13.313.65

Answers to Exercise 13.313.66

13.5 Legendre Functions 13.66

13.5.1 Series Solution of Legendre’s Differential Equation 13.66

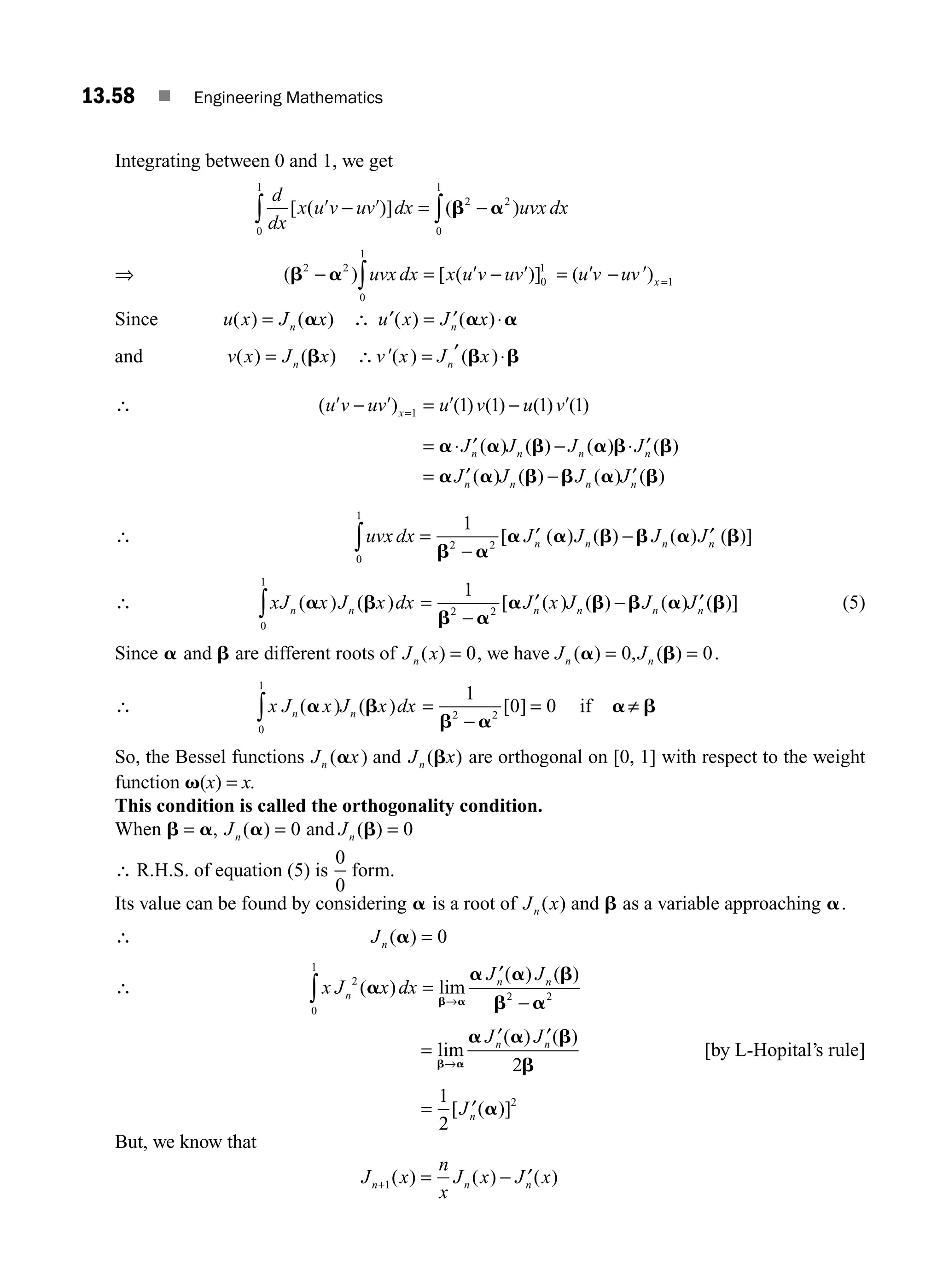

13.5.2 Legendre Polynomials 13.71

13.5.3 Rodrigue’s Formula 13.71

Worked Examples13.73

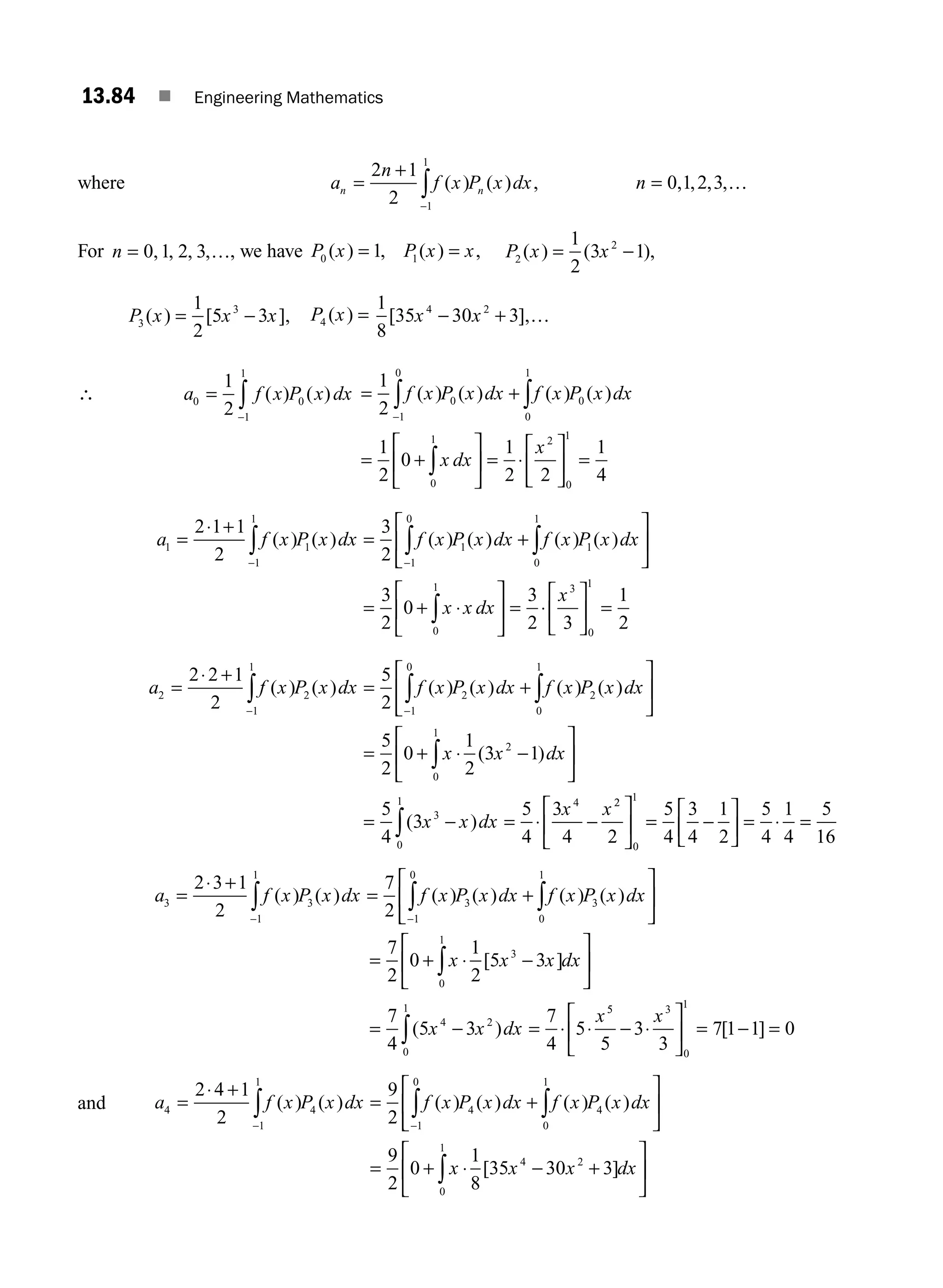

13.5.4 Generating Function for Legendre Polynomials 13.74

Worked Examples13.75

13.5.5 Orthogonality of Legendre Polynomials in [-1, 1] 13.77

Worked Examples13.80

13.5.6 Fourier–Legendre Expansion of f(x) in a Series of Legendre

Polynomials13.83

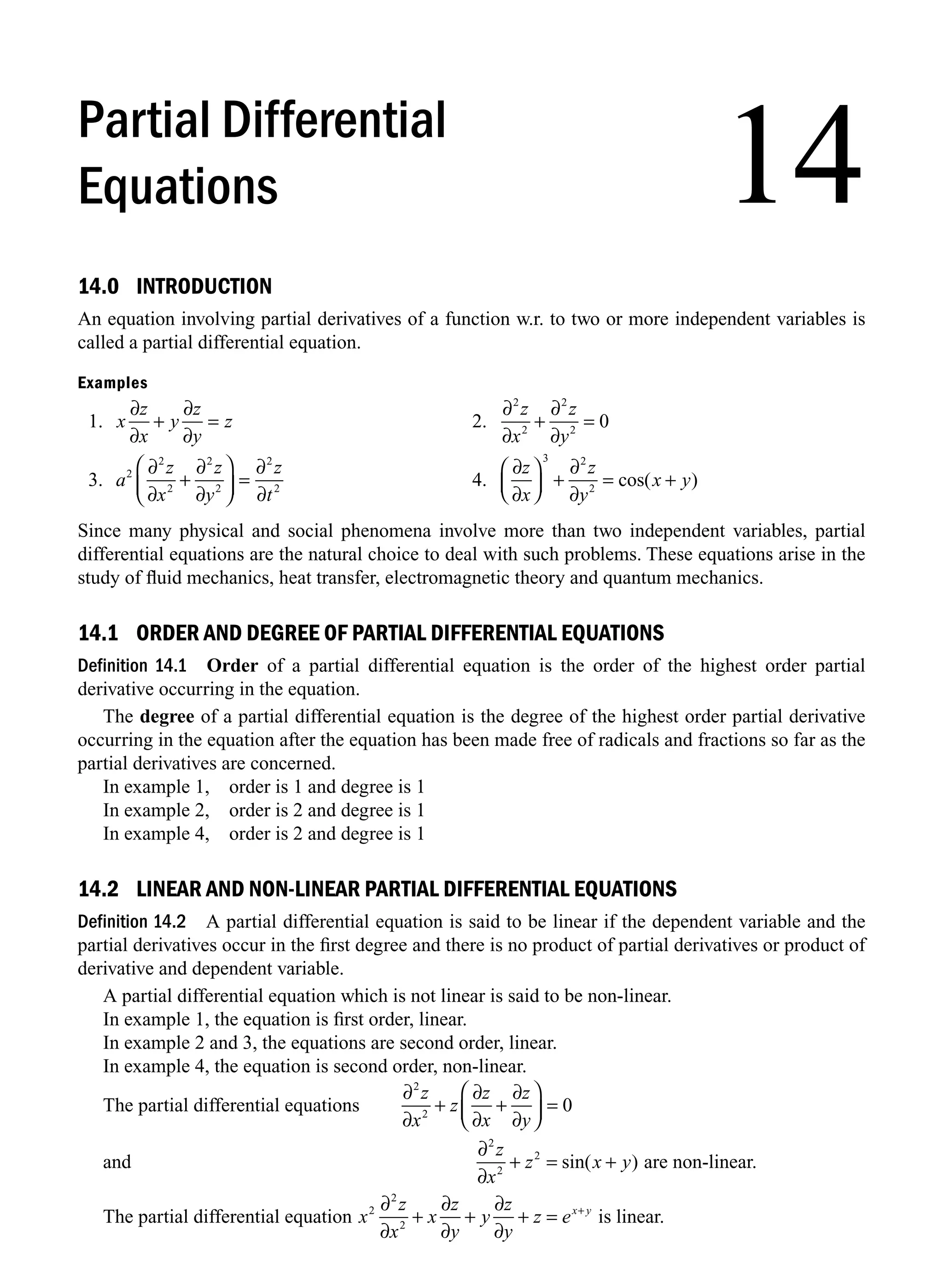

Worked Examples13.83

Exercise 13.413.85

Answers to Exercise 13.413.85

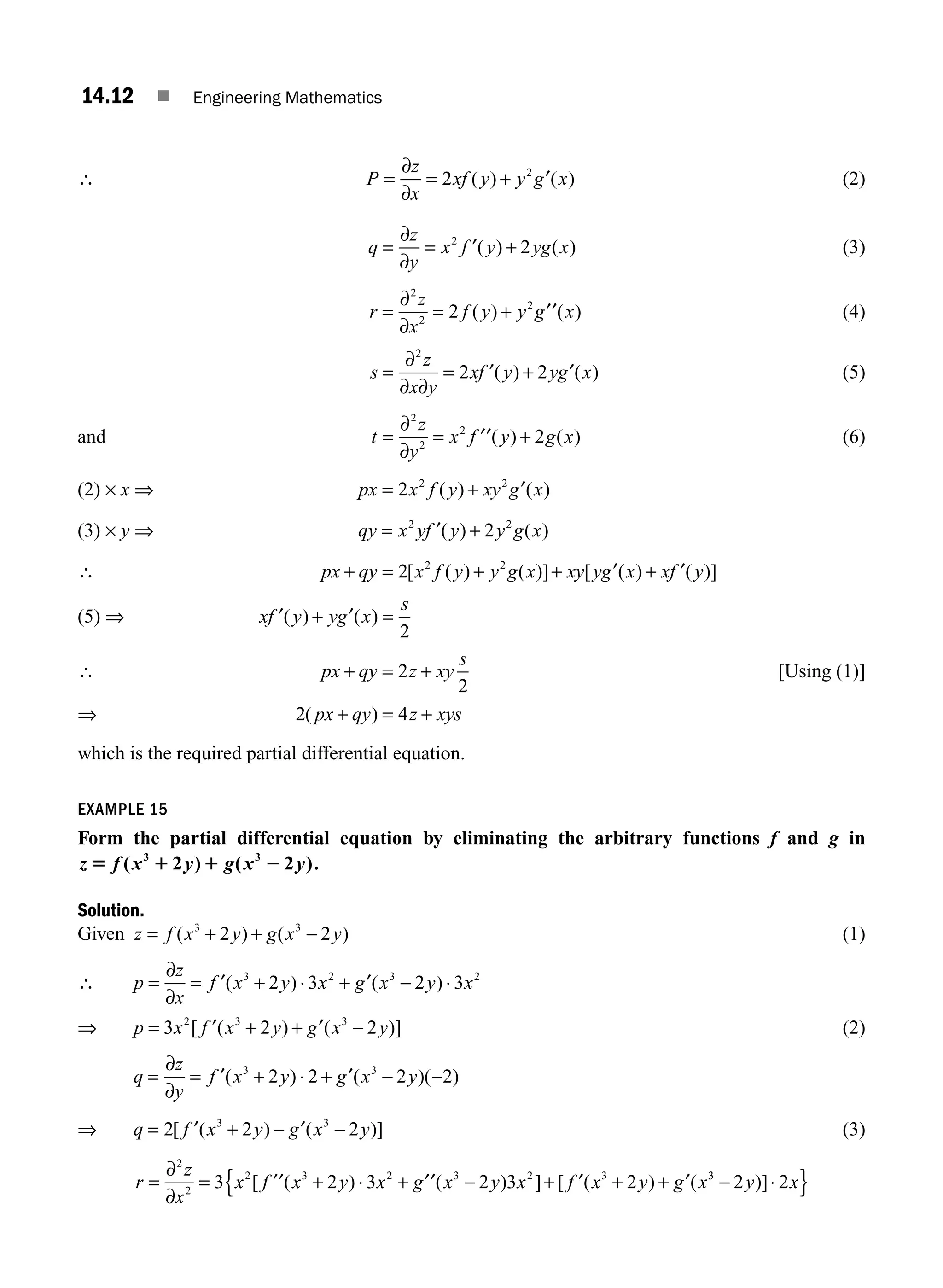

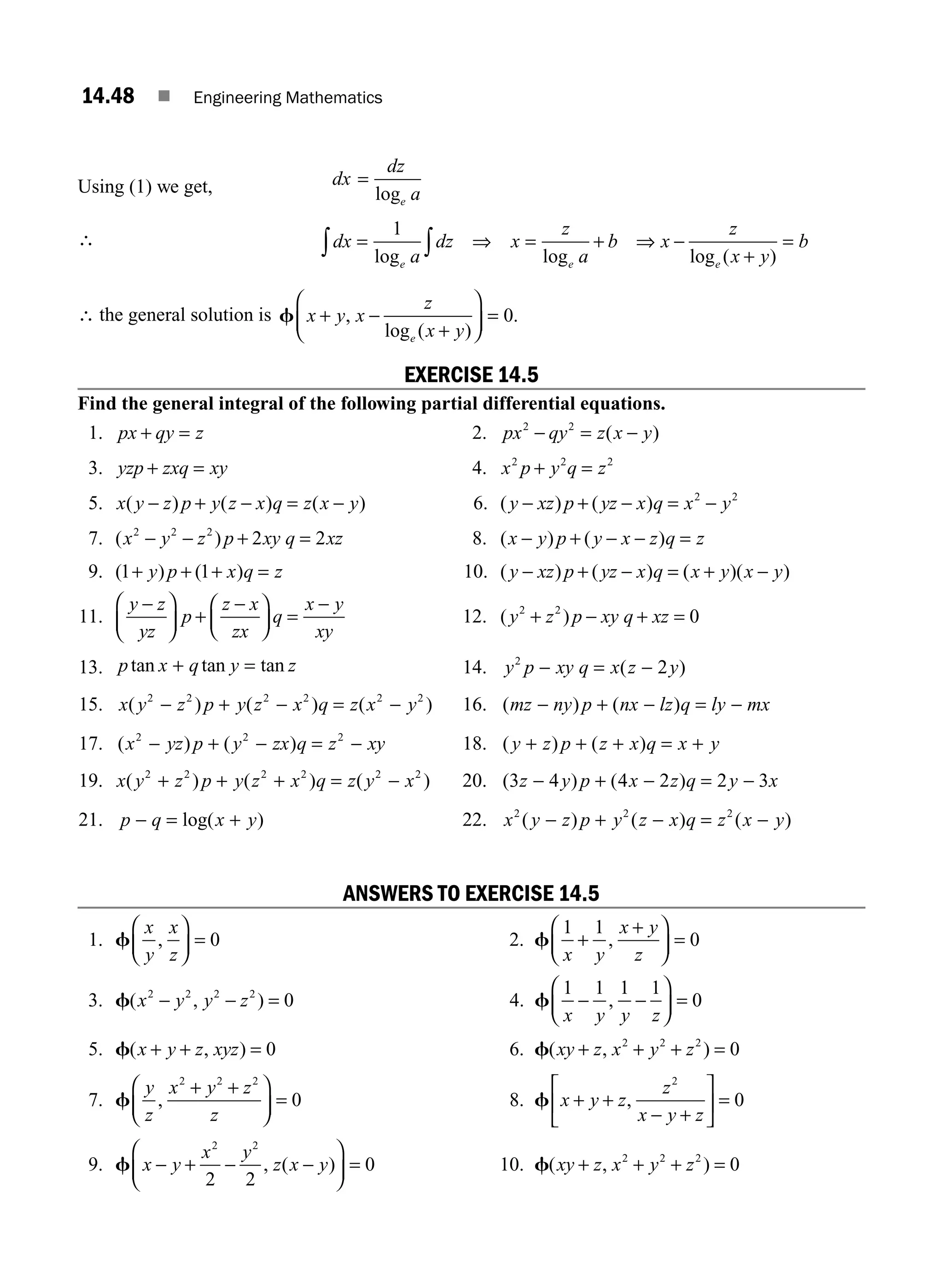

14. Partial Differential Equations 14.1

14.0 Introduction 14.1

14.1 Order and Degree of Partial Differential Equations 14.1

14.2 Linear and Non-linear Partial Differential Equations 14.1

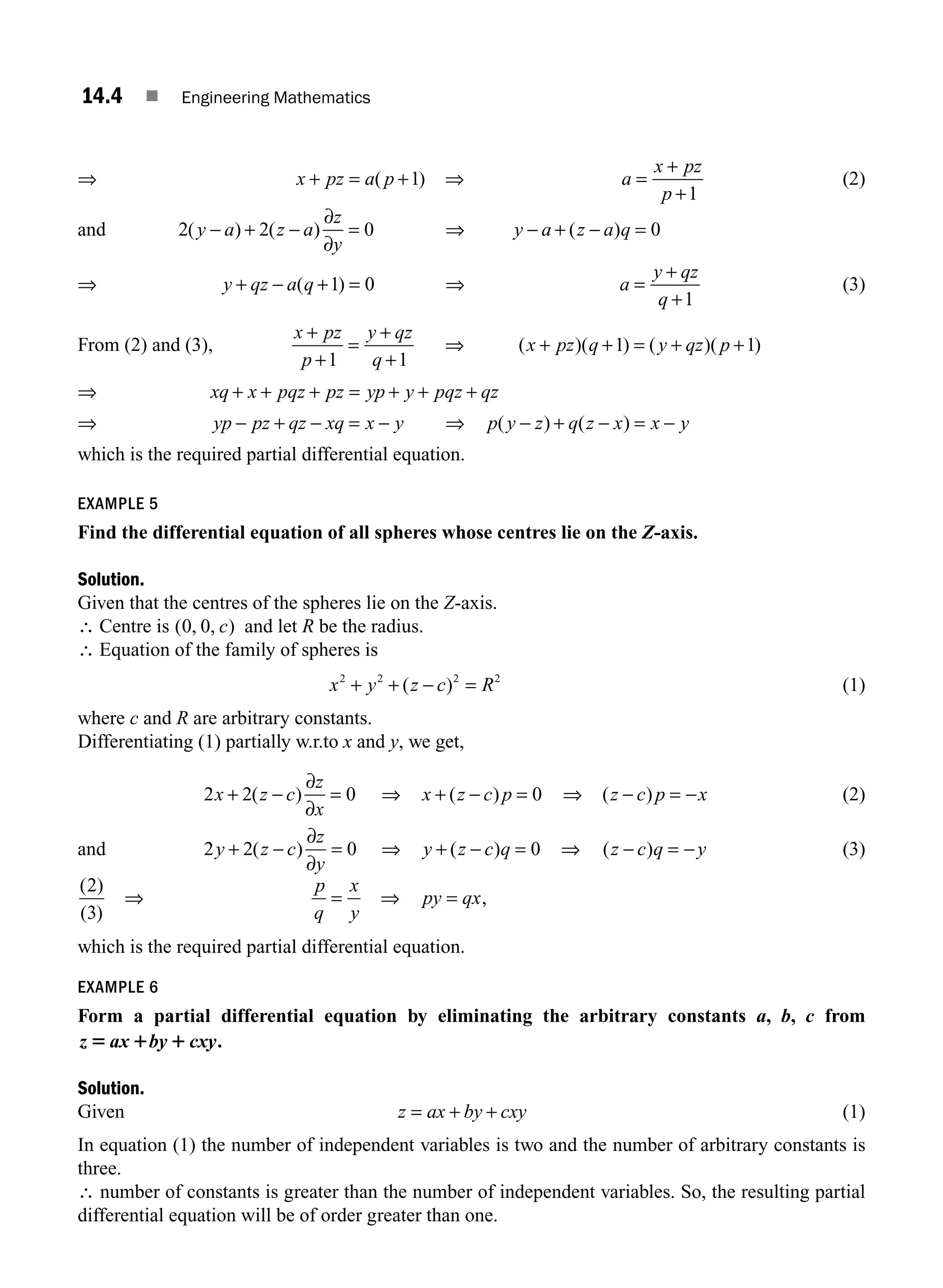

14.3 Formation of Partial Differential Equations 14.2

Worked Examples 14.2

Exercise 14.114.15

Answers to Exercise 14.114.15

A01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _FM - (Reprint).indd 24 3/2/2017 6:17:55 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-25-2048.jpg)

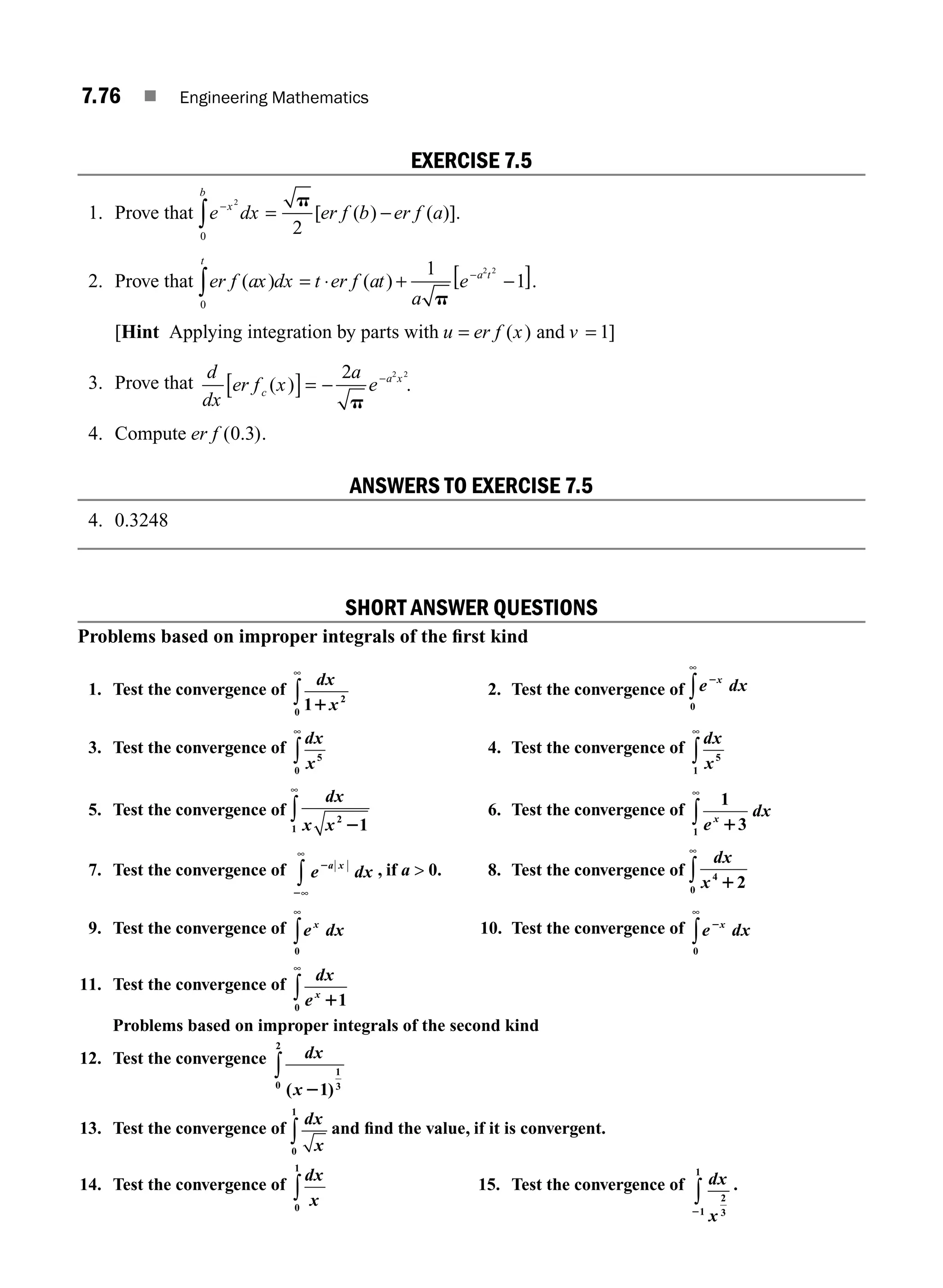

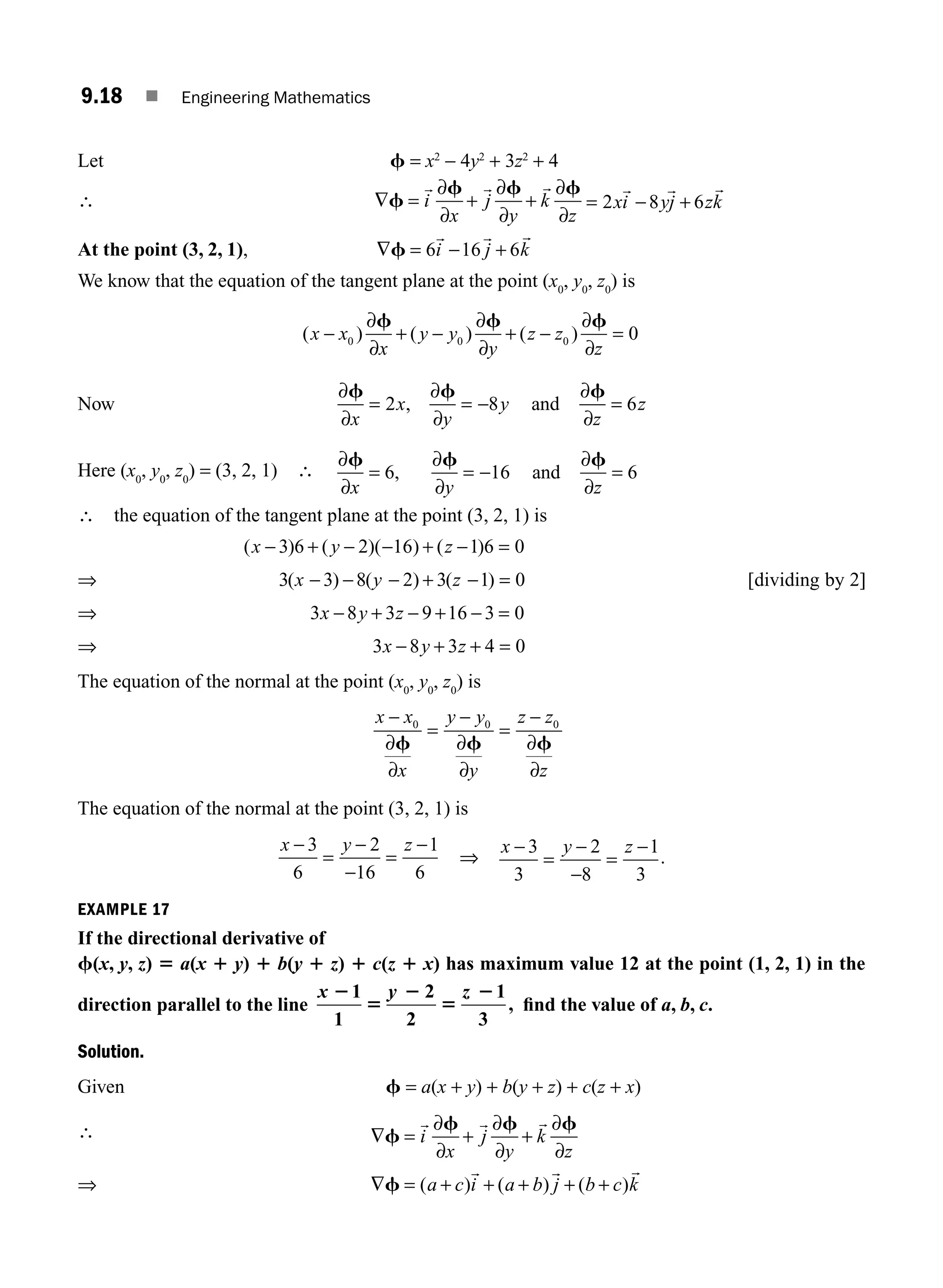

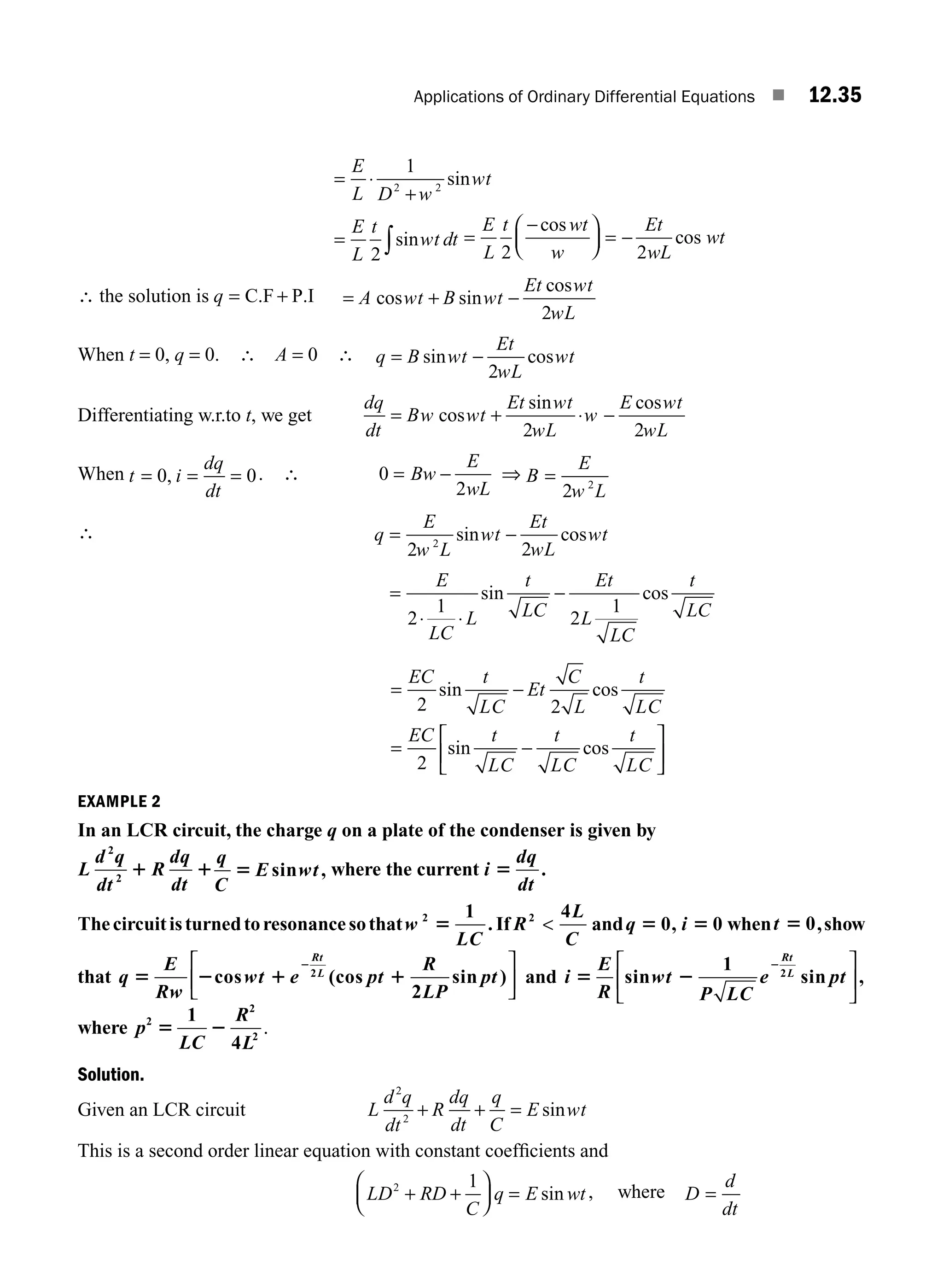

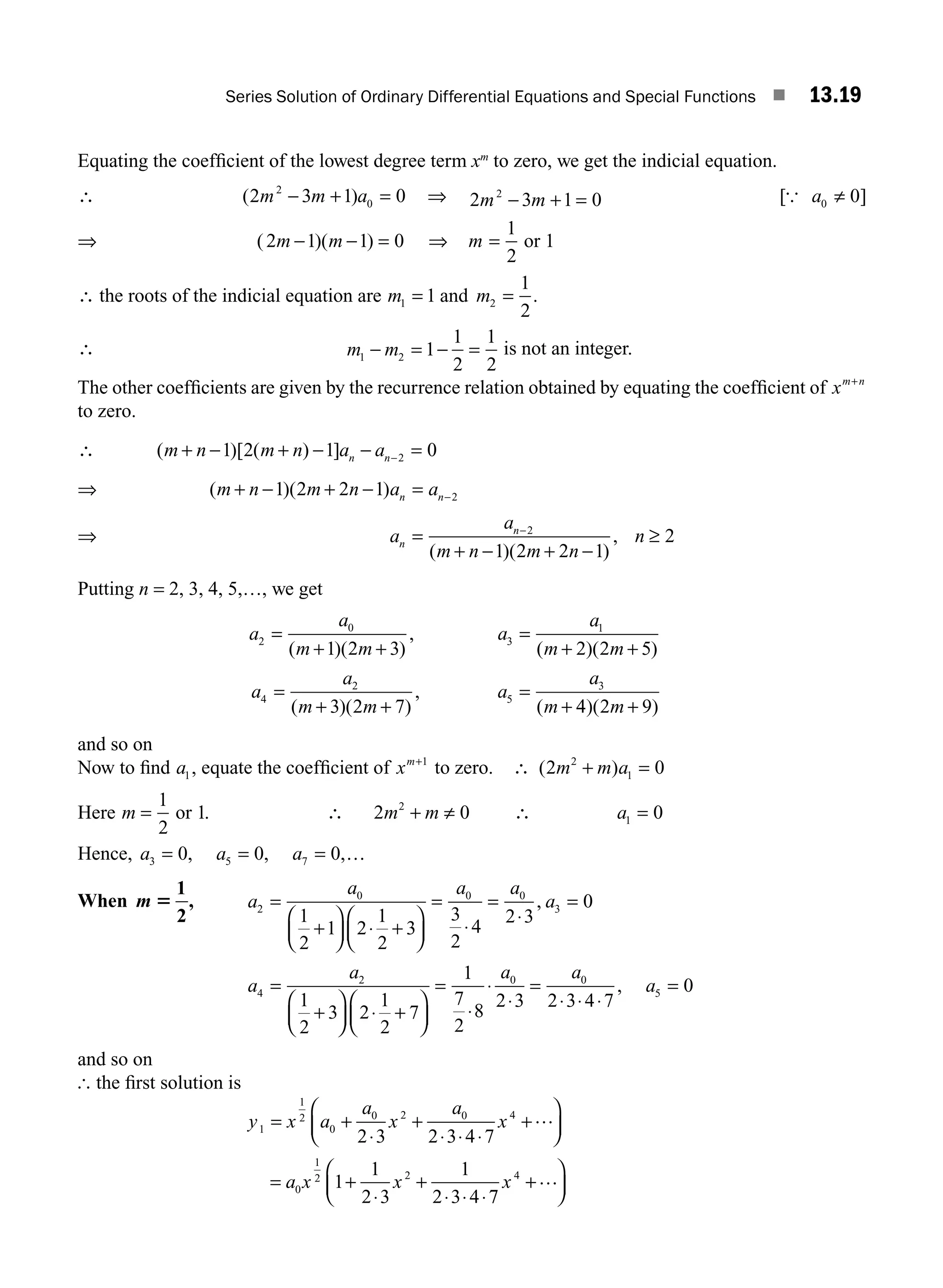

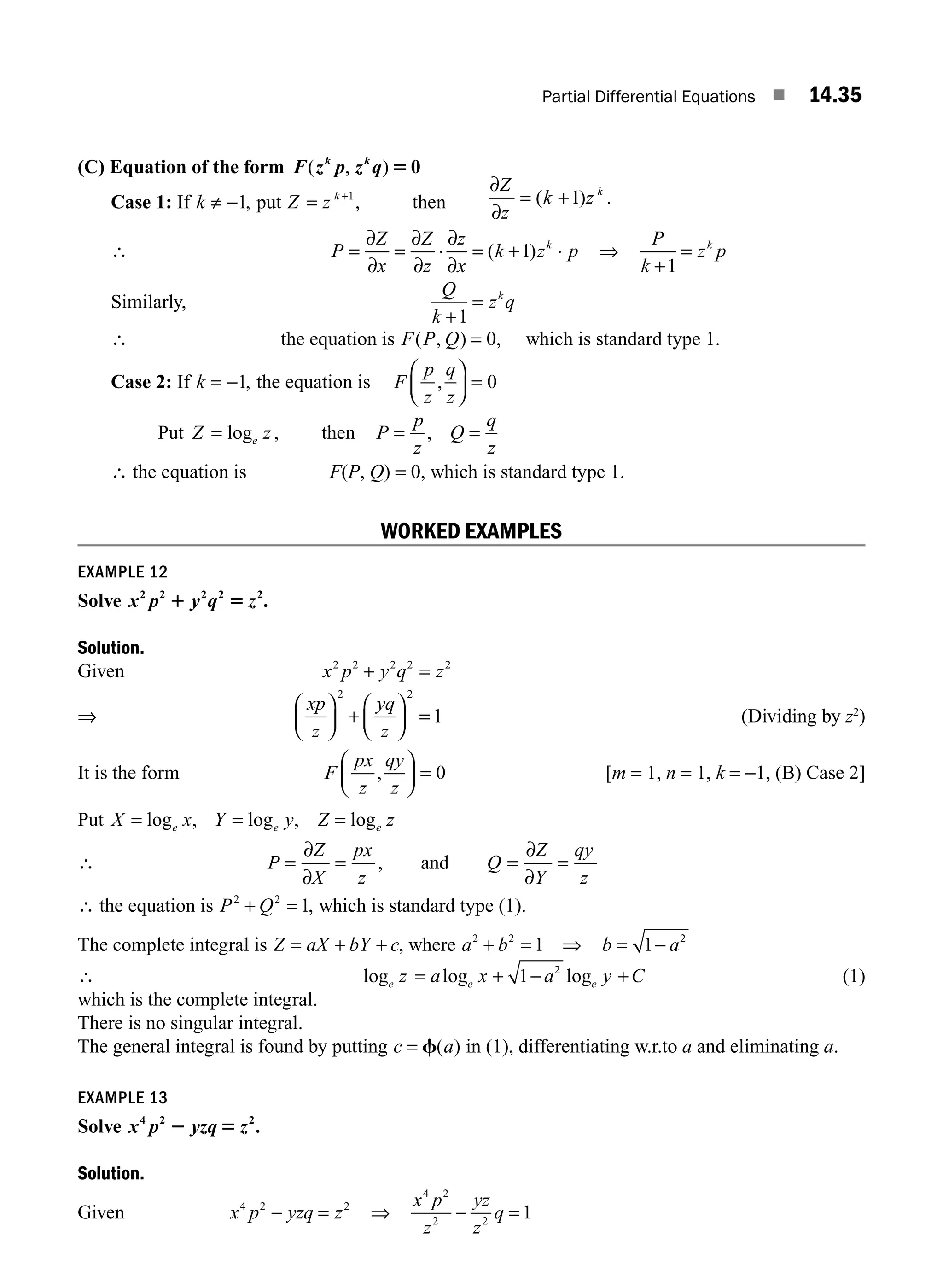

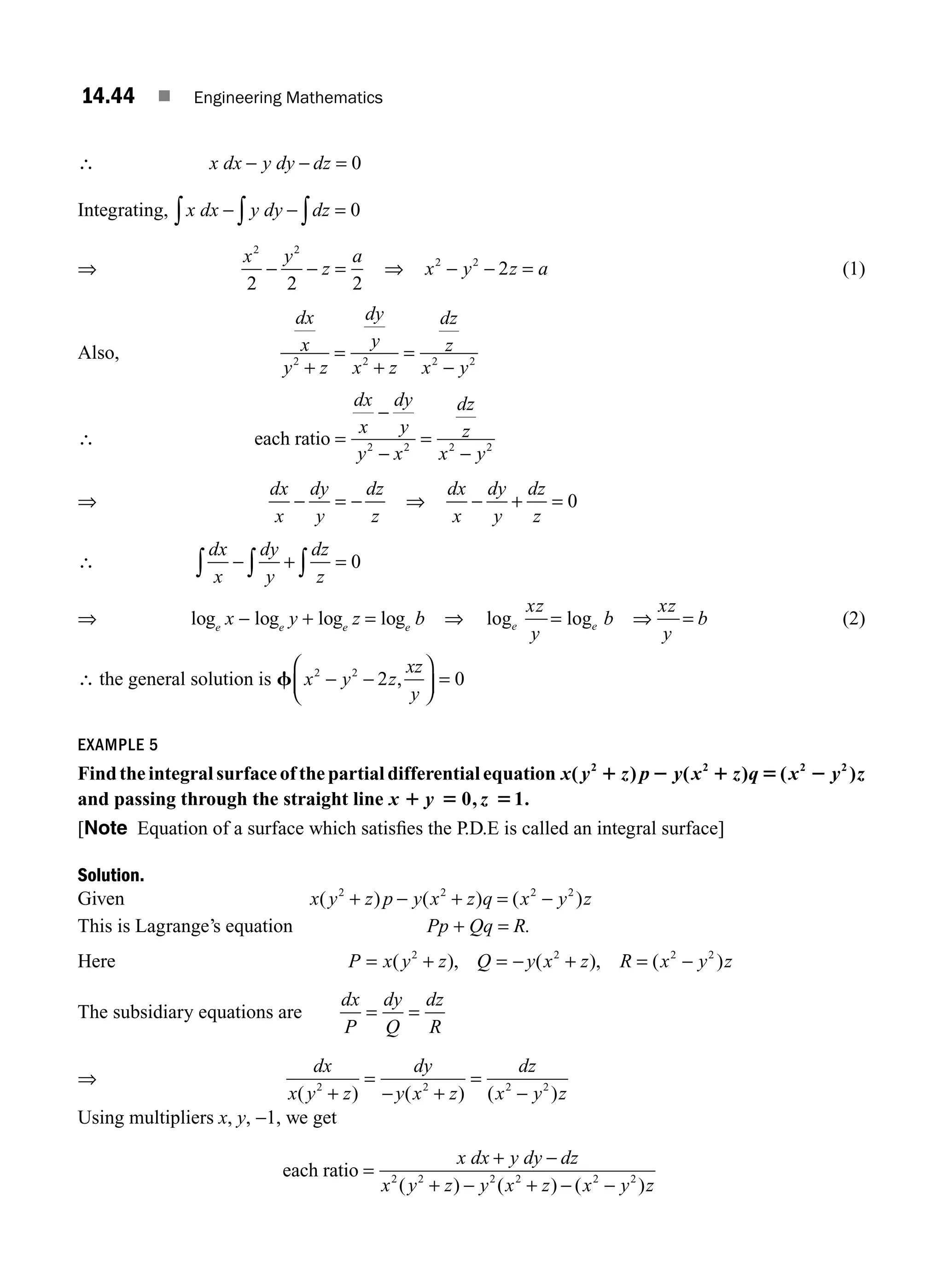

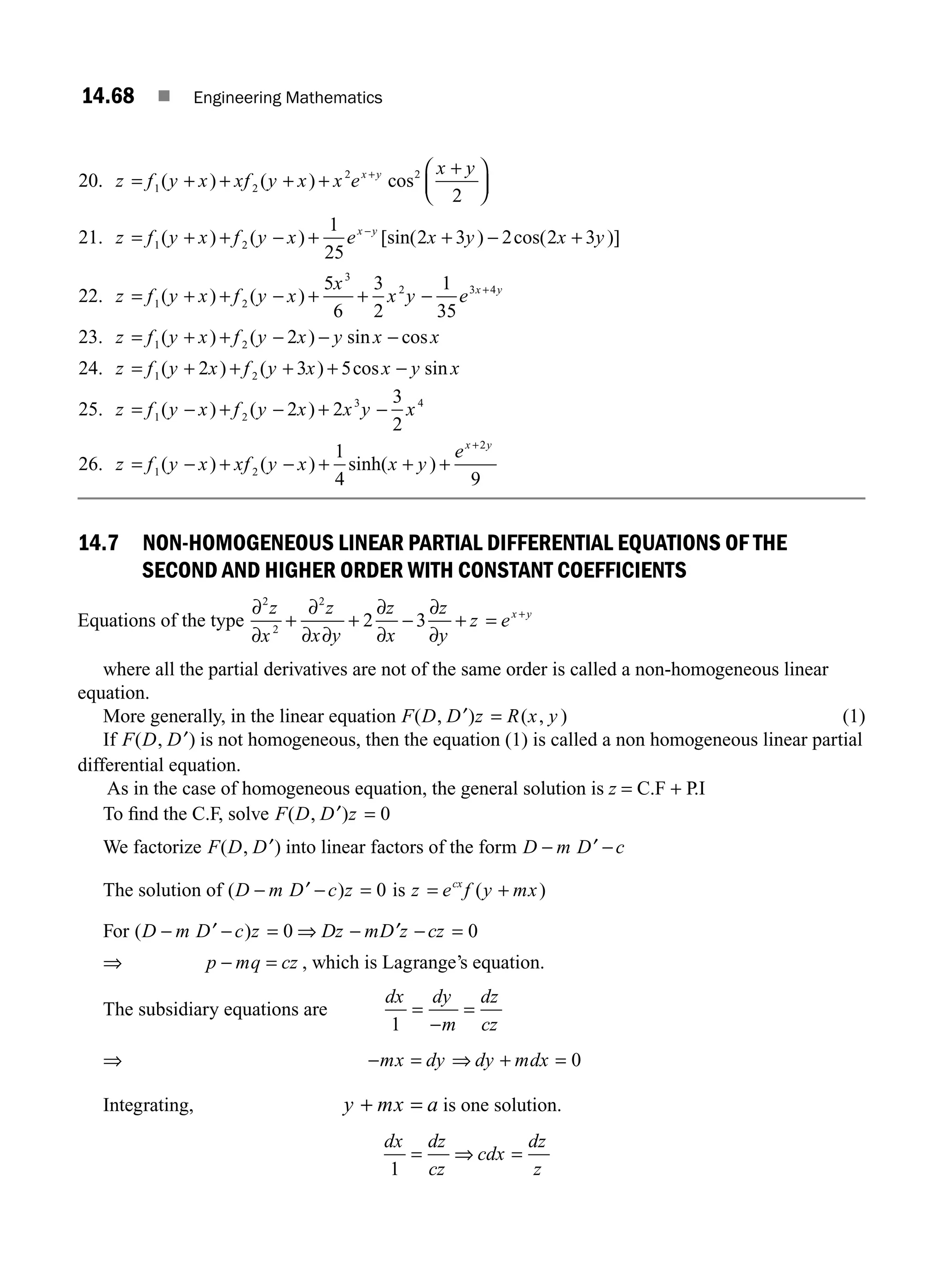

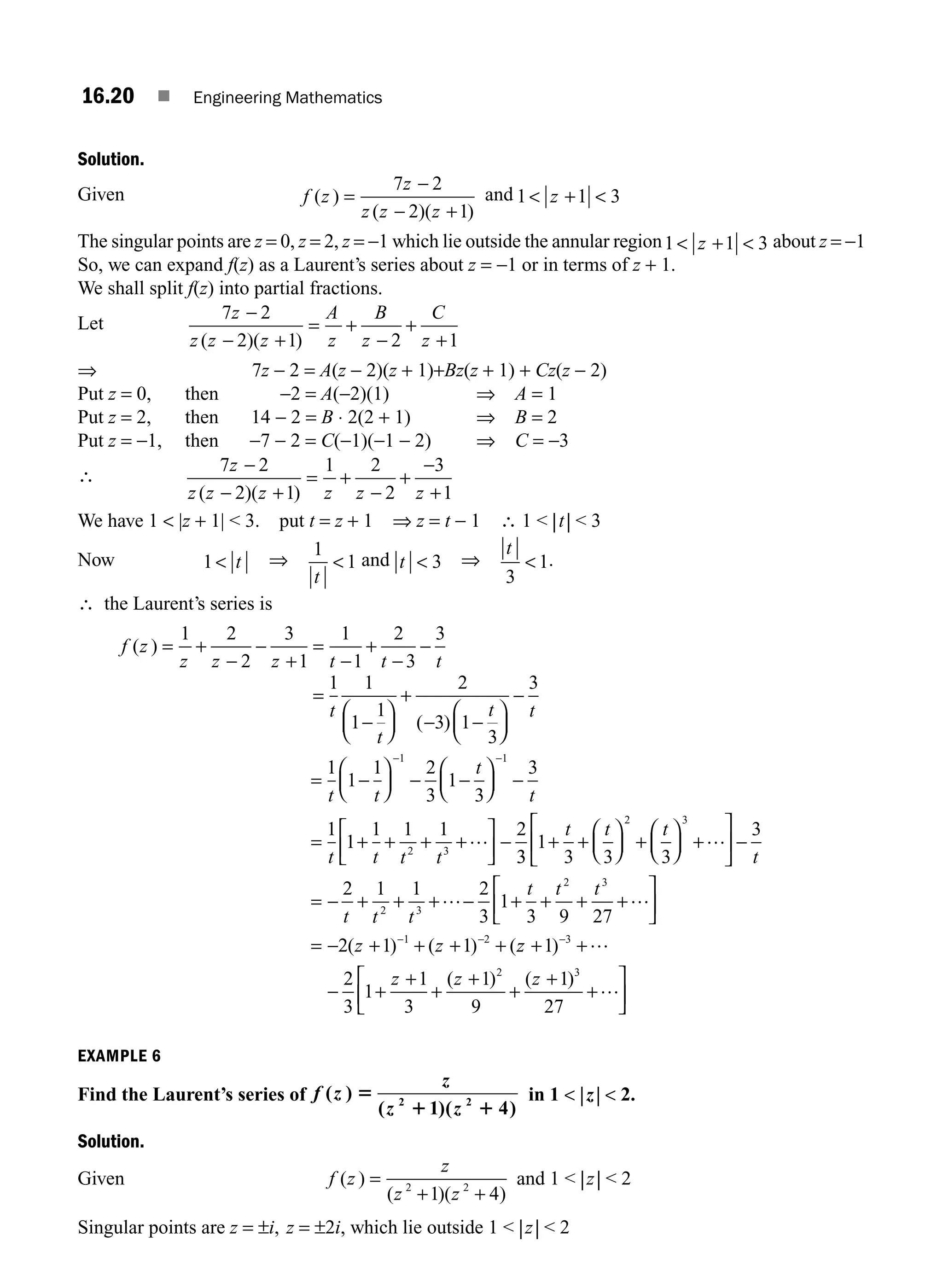

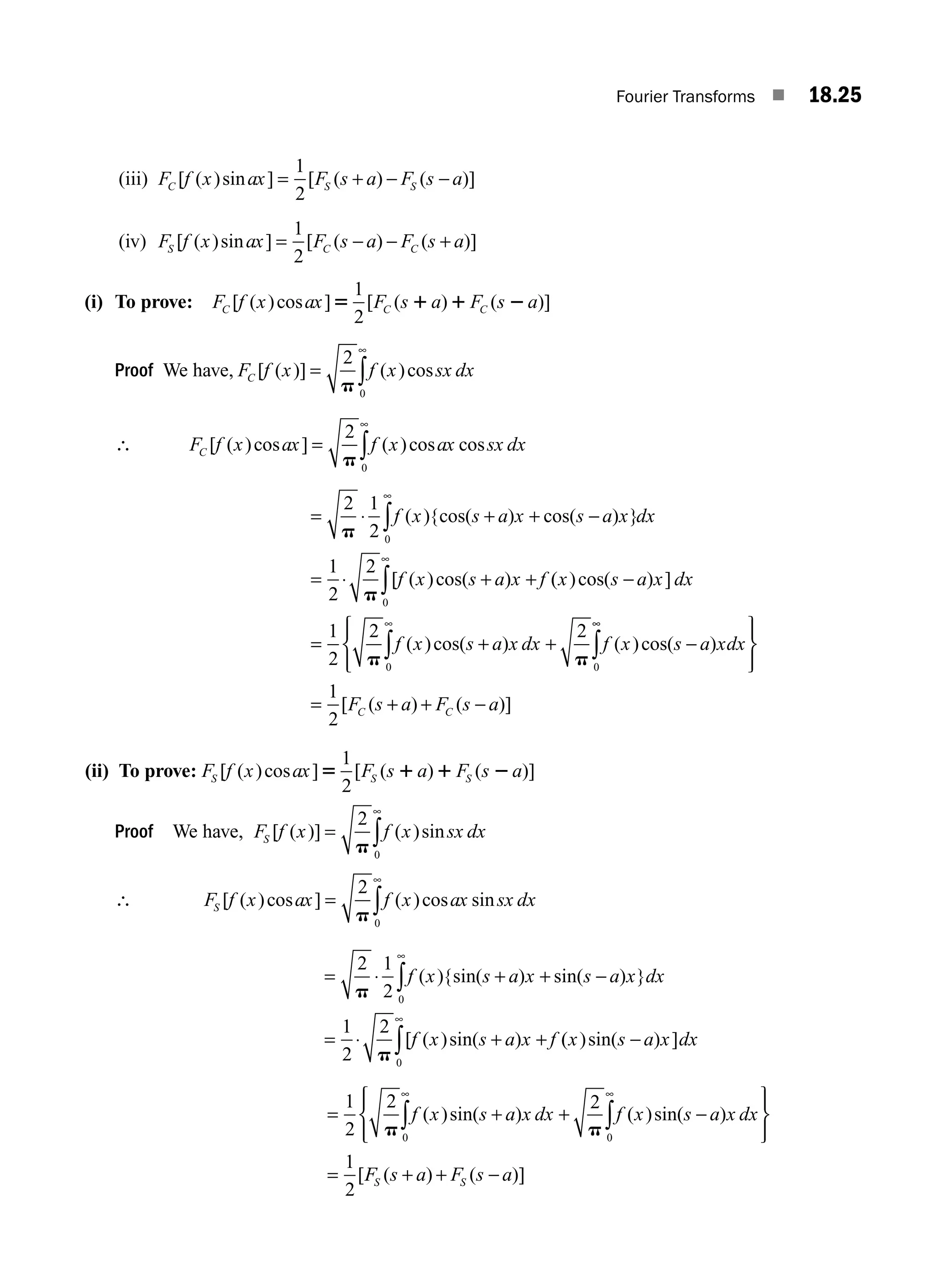

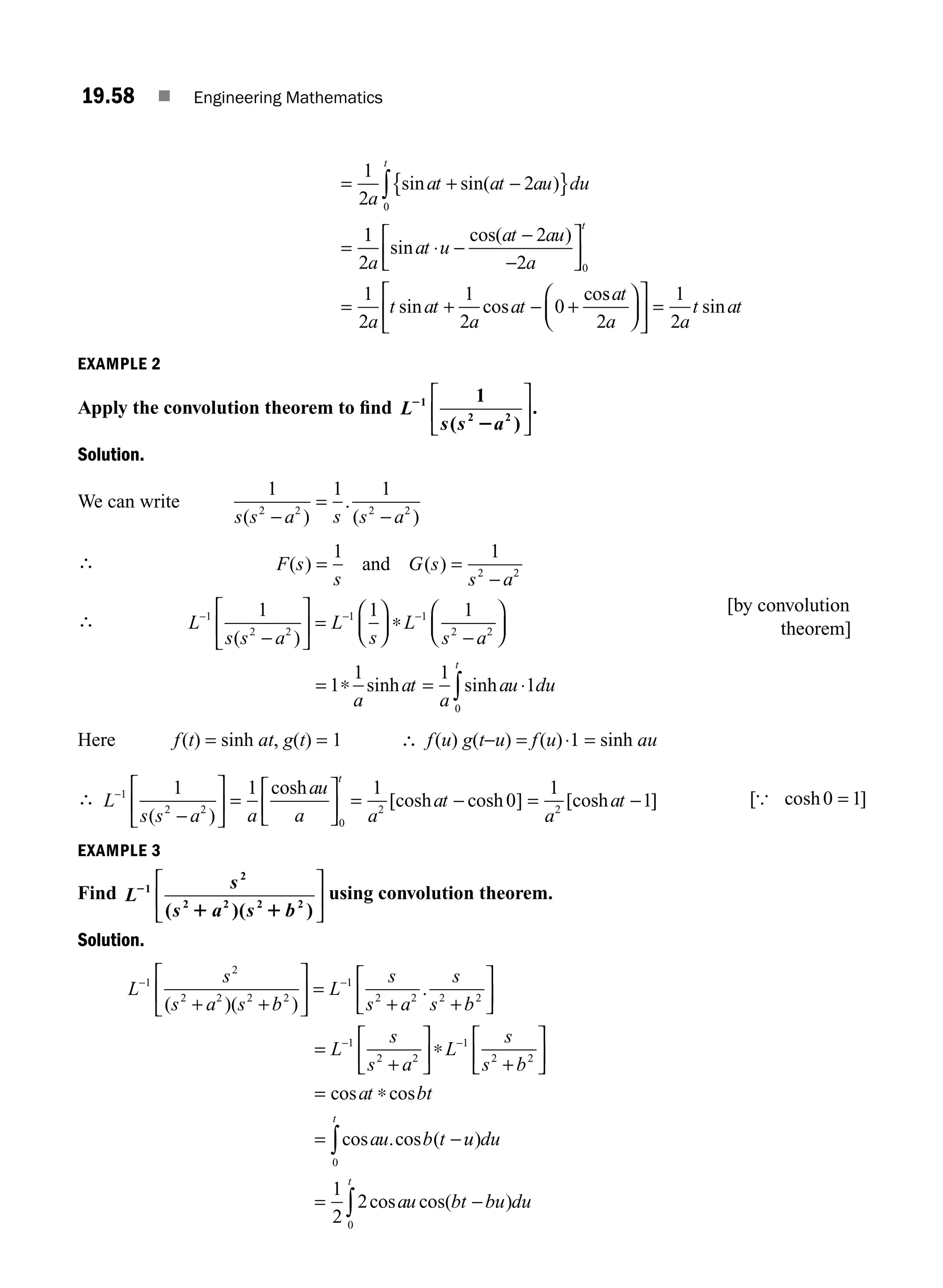

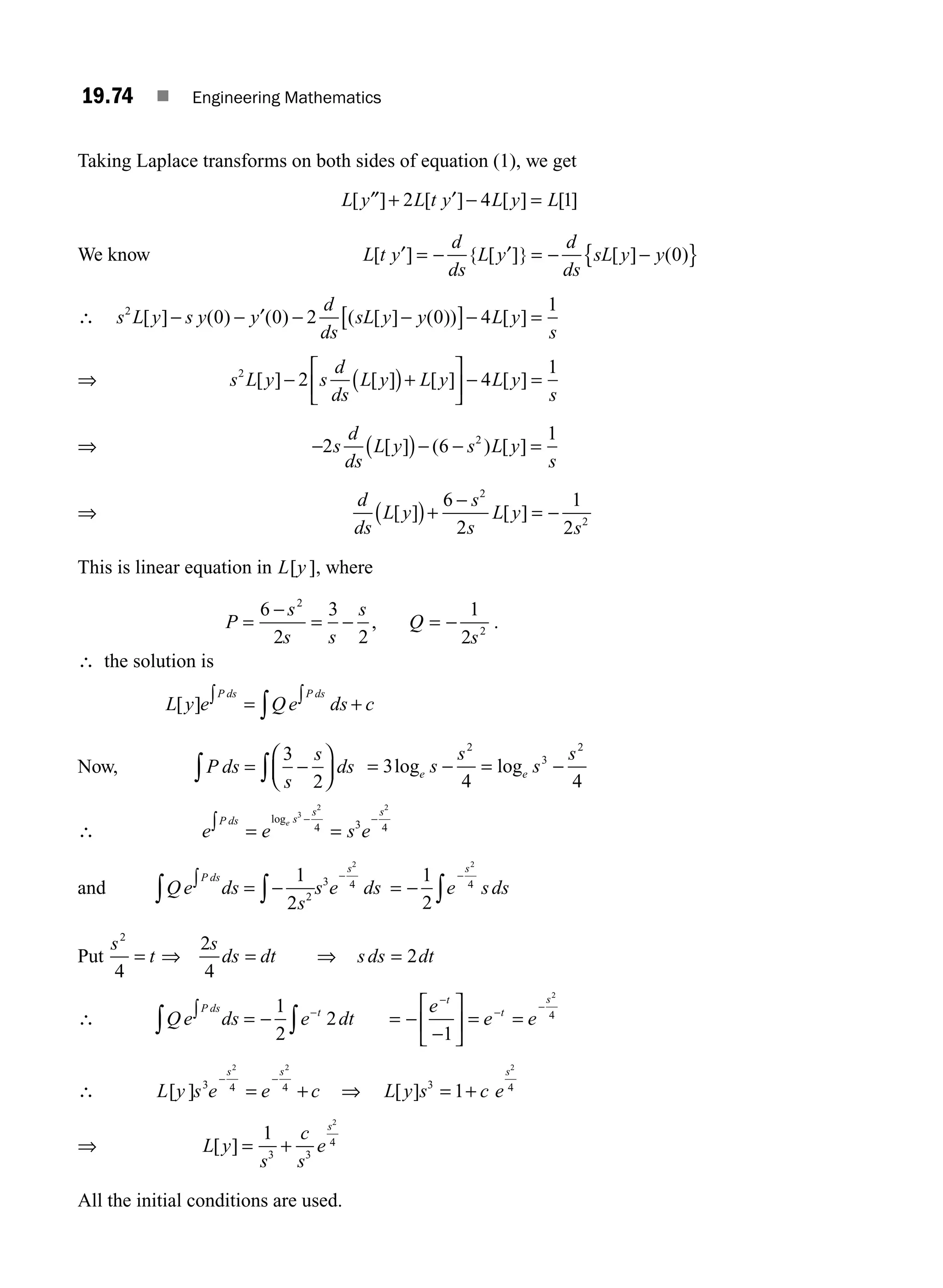

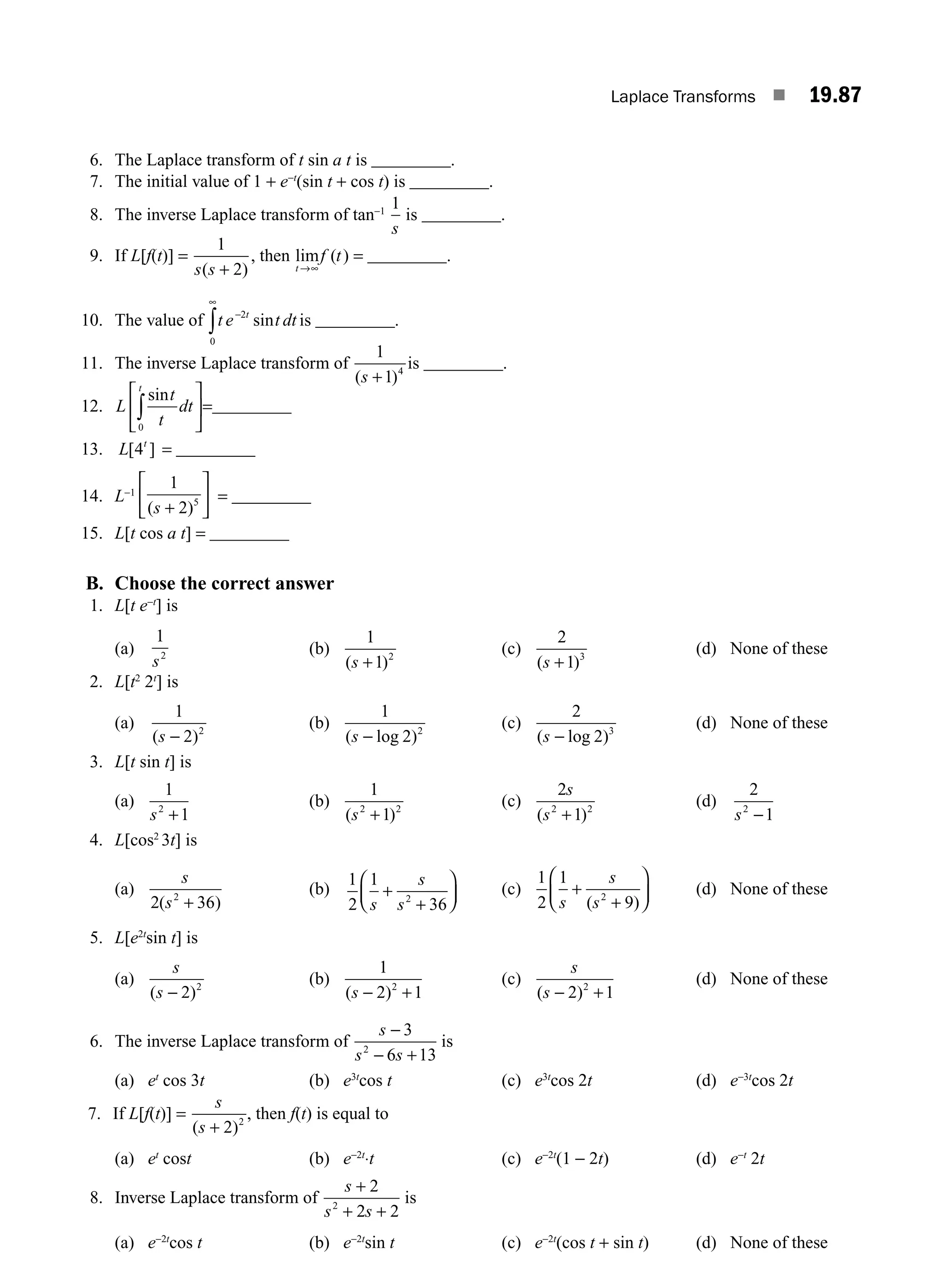

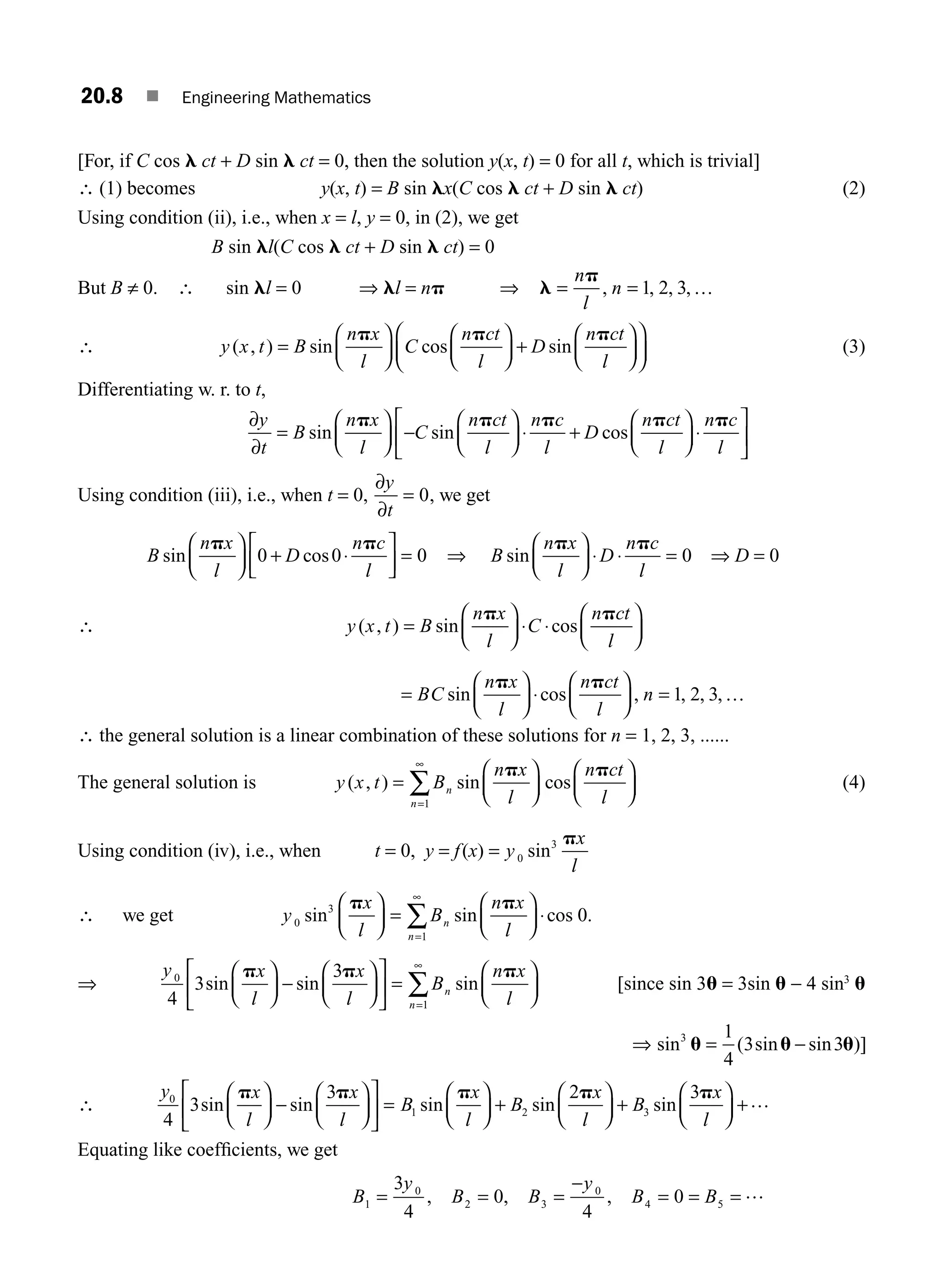

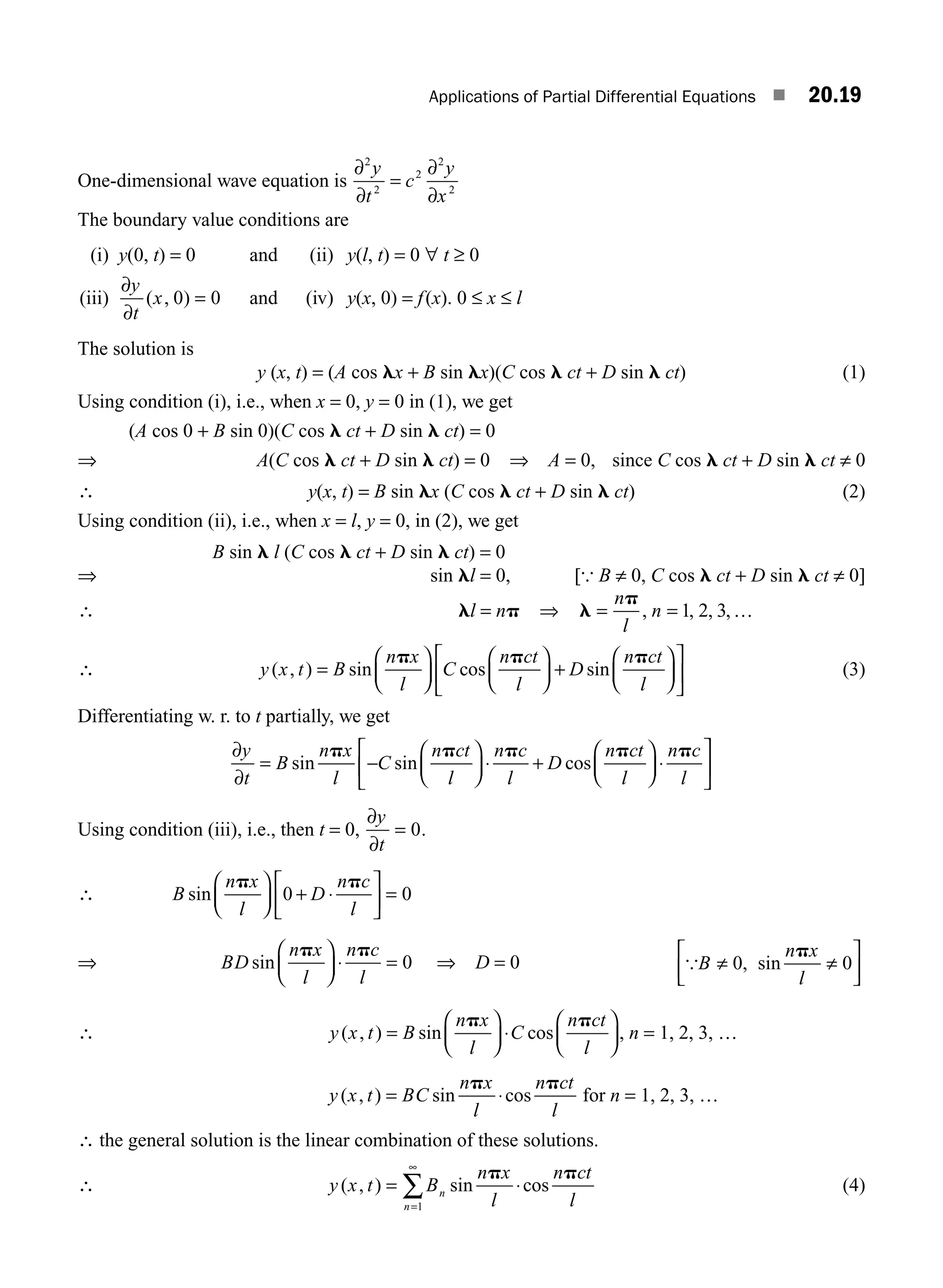

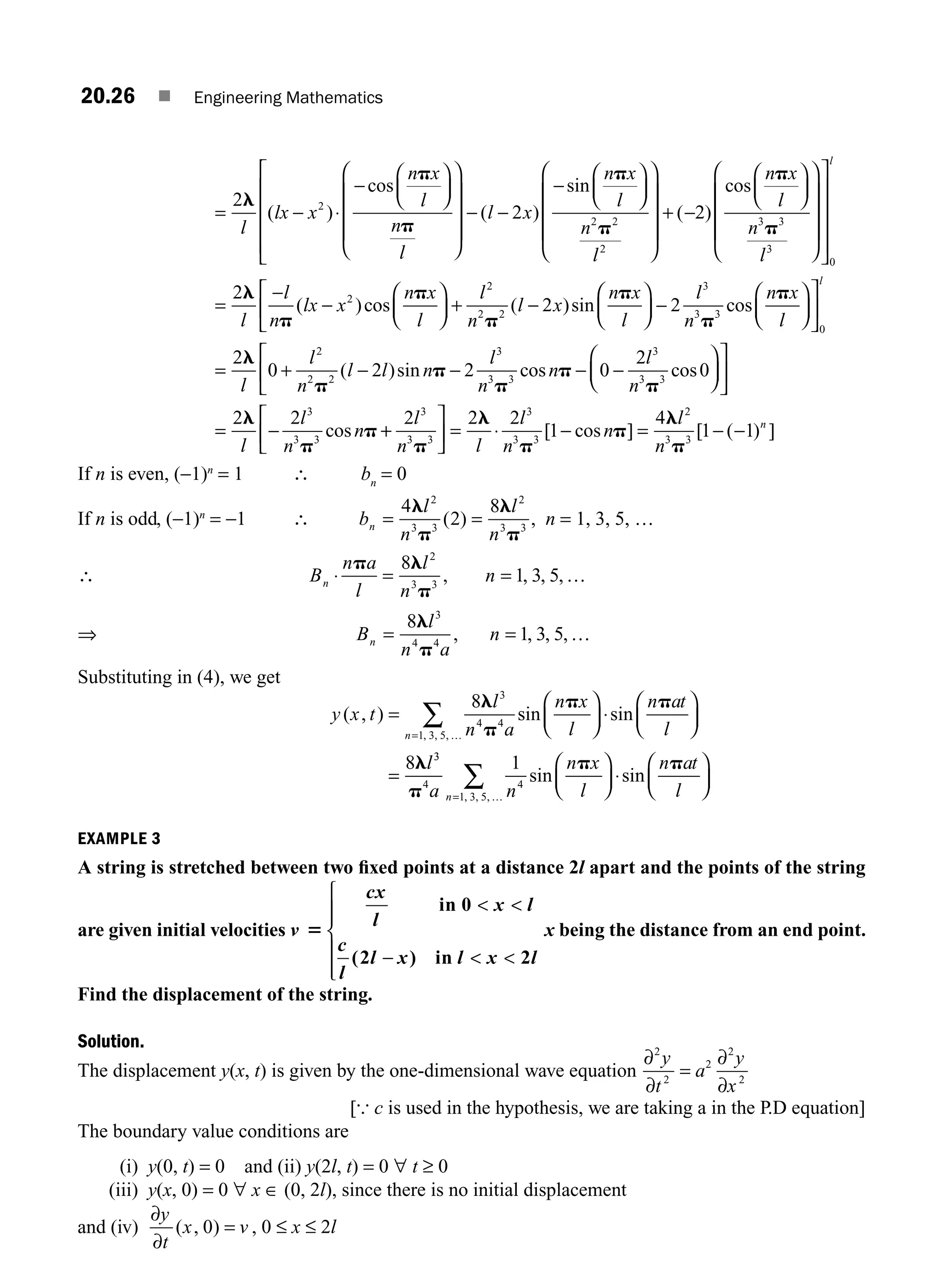

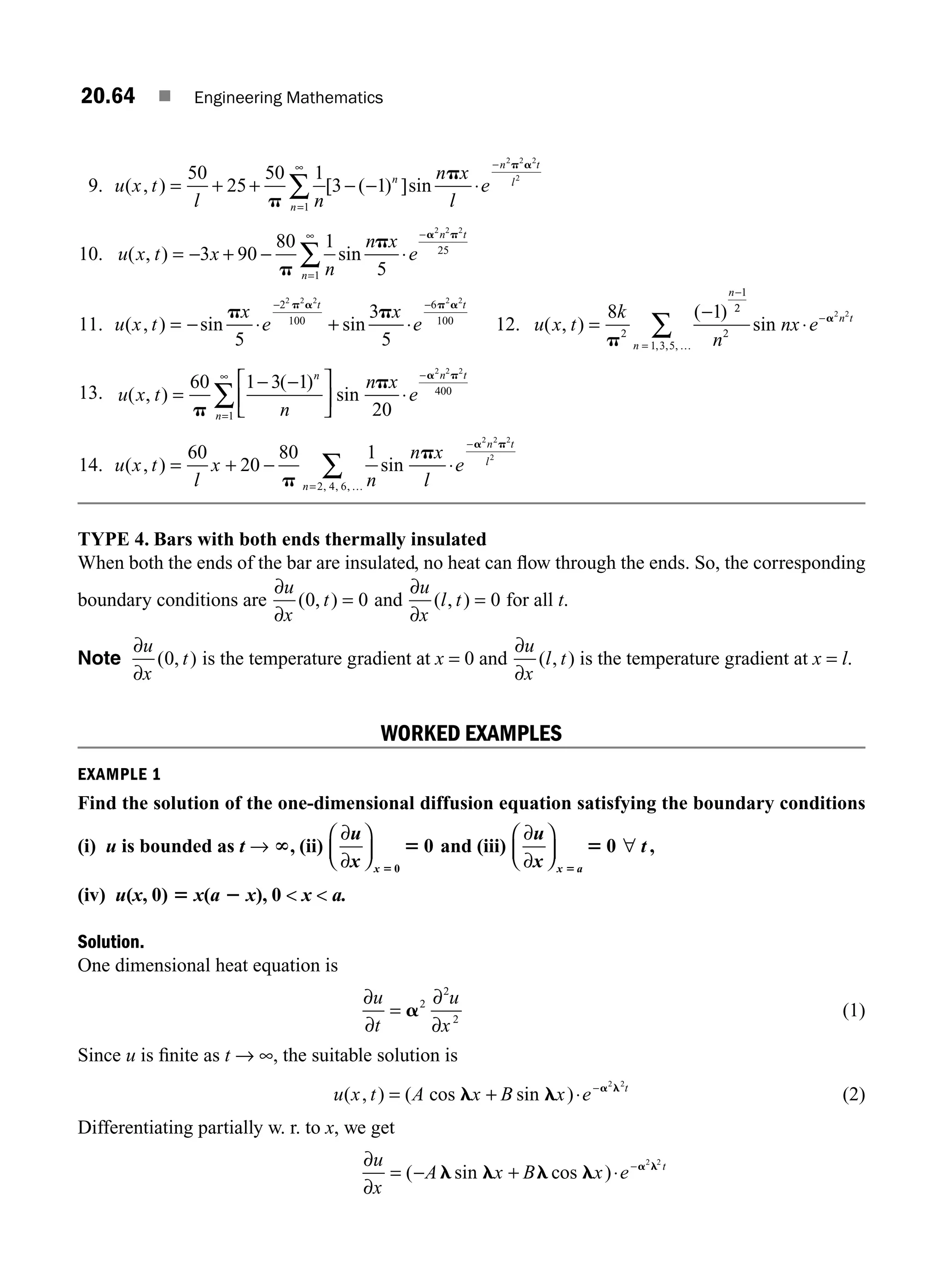

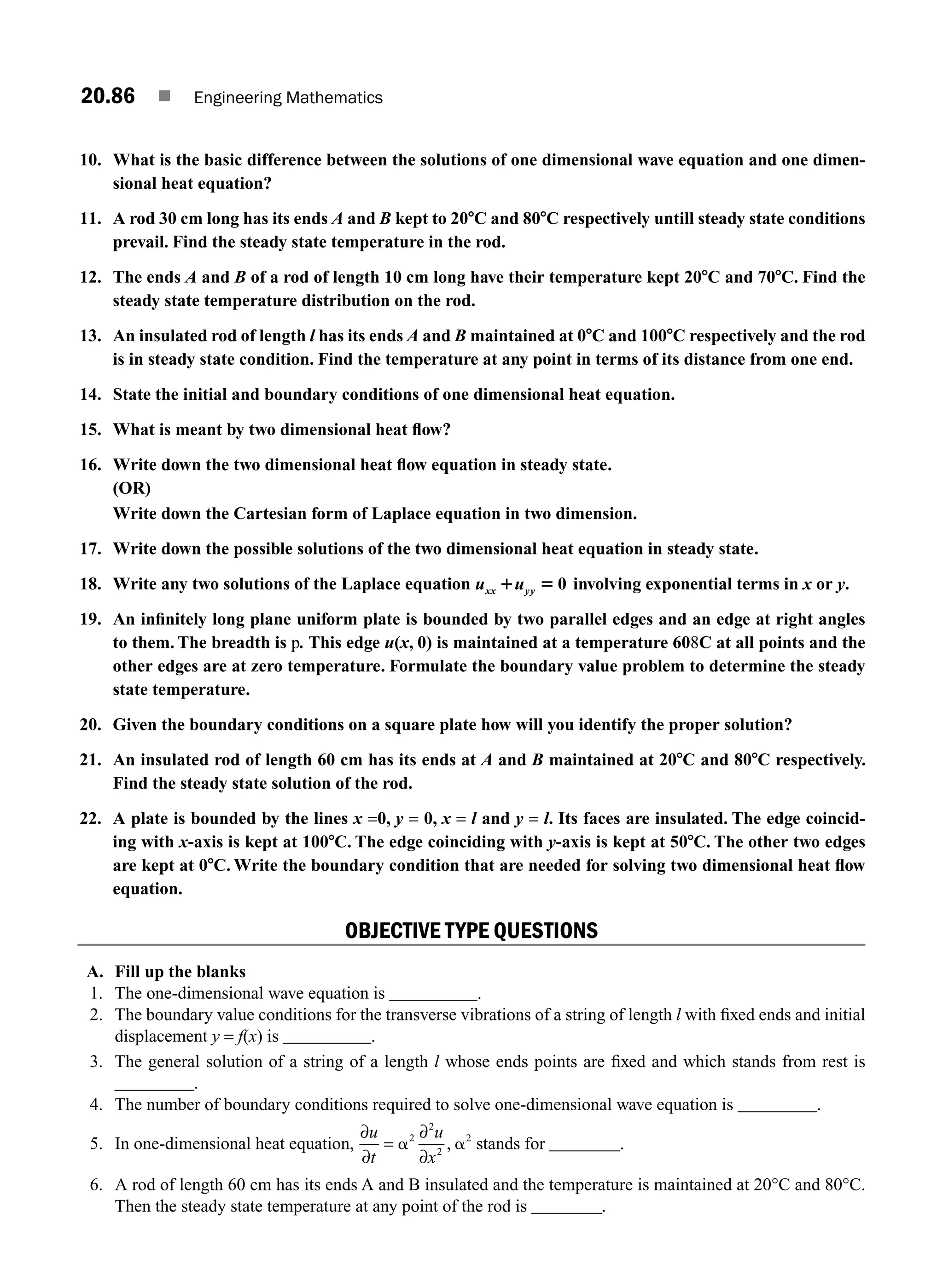

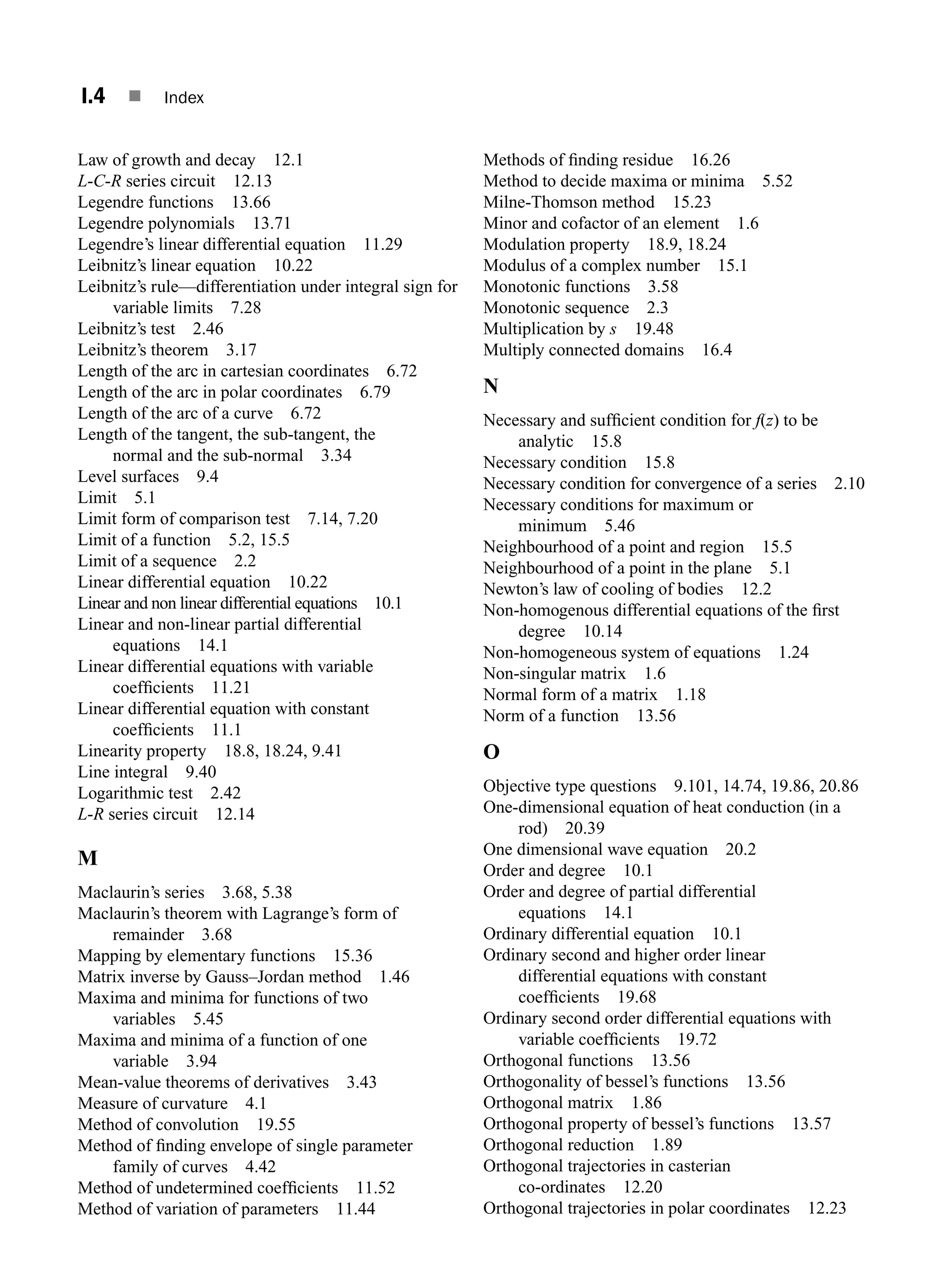

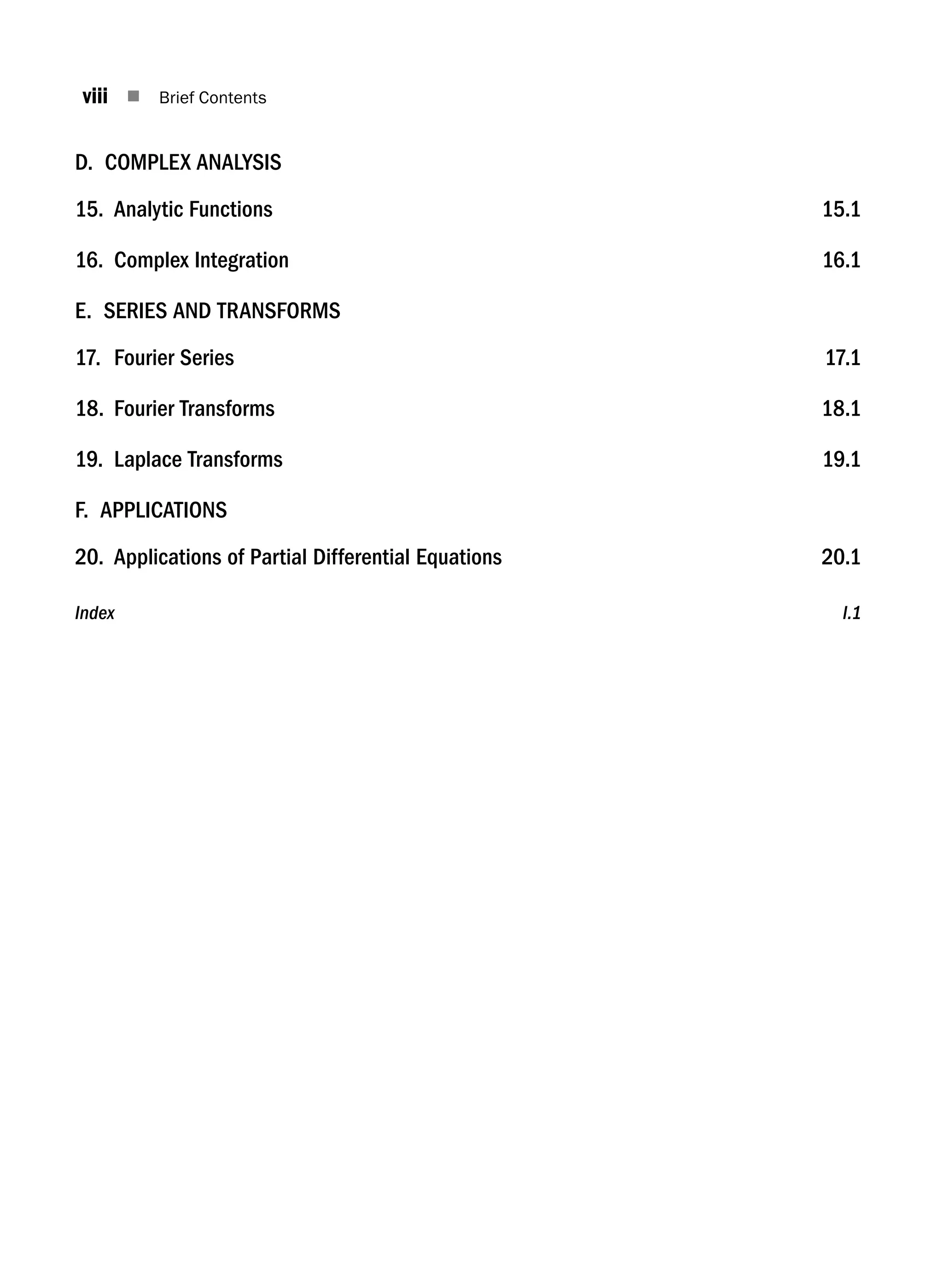

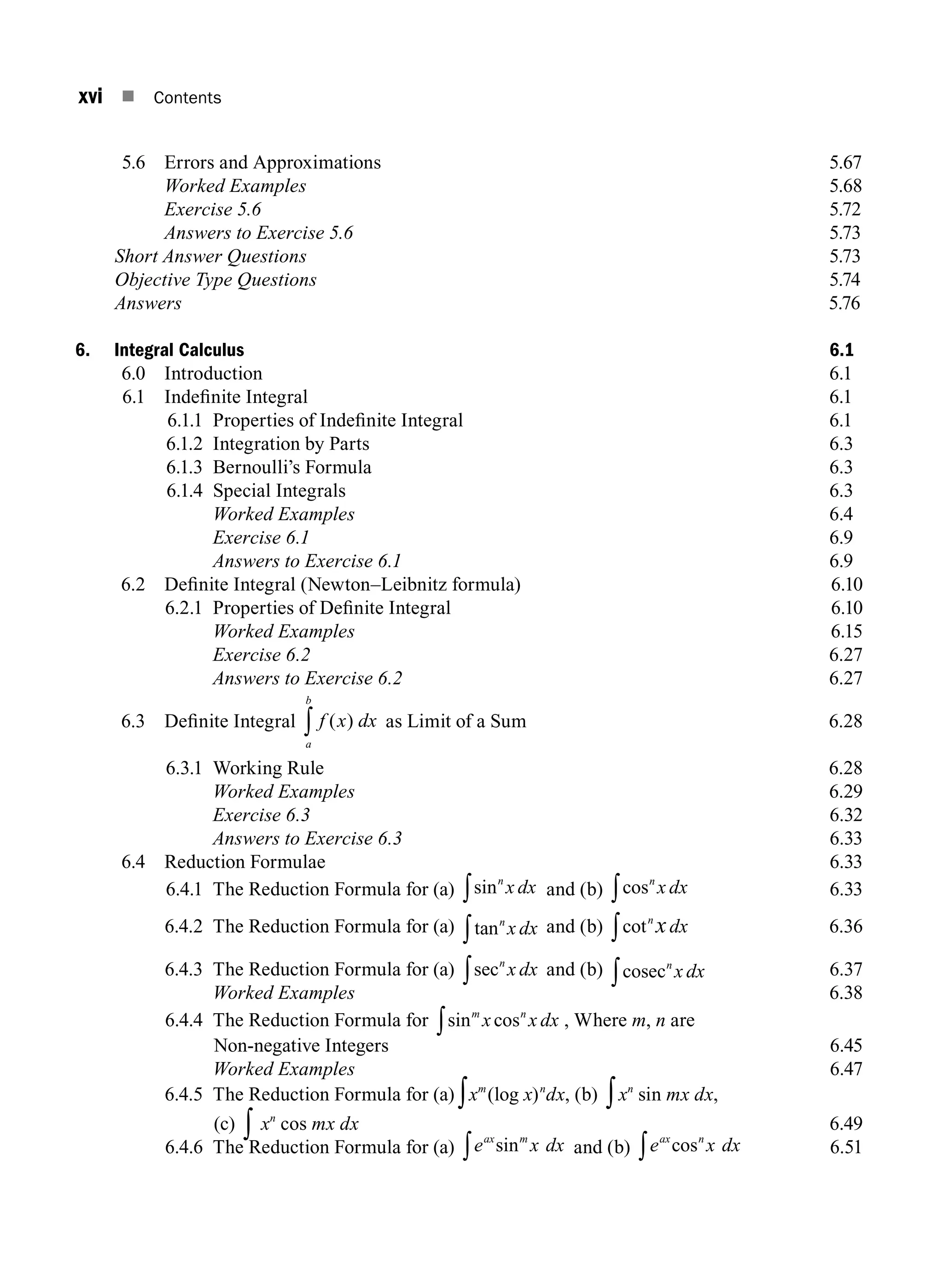

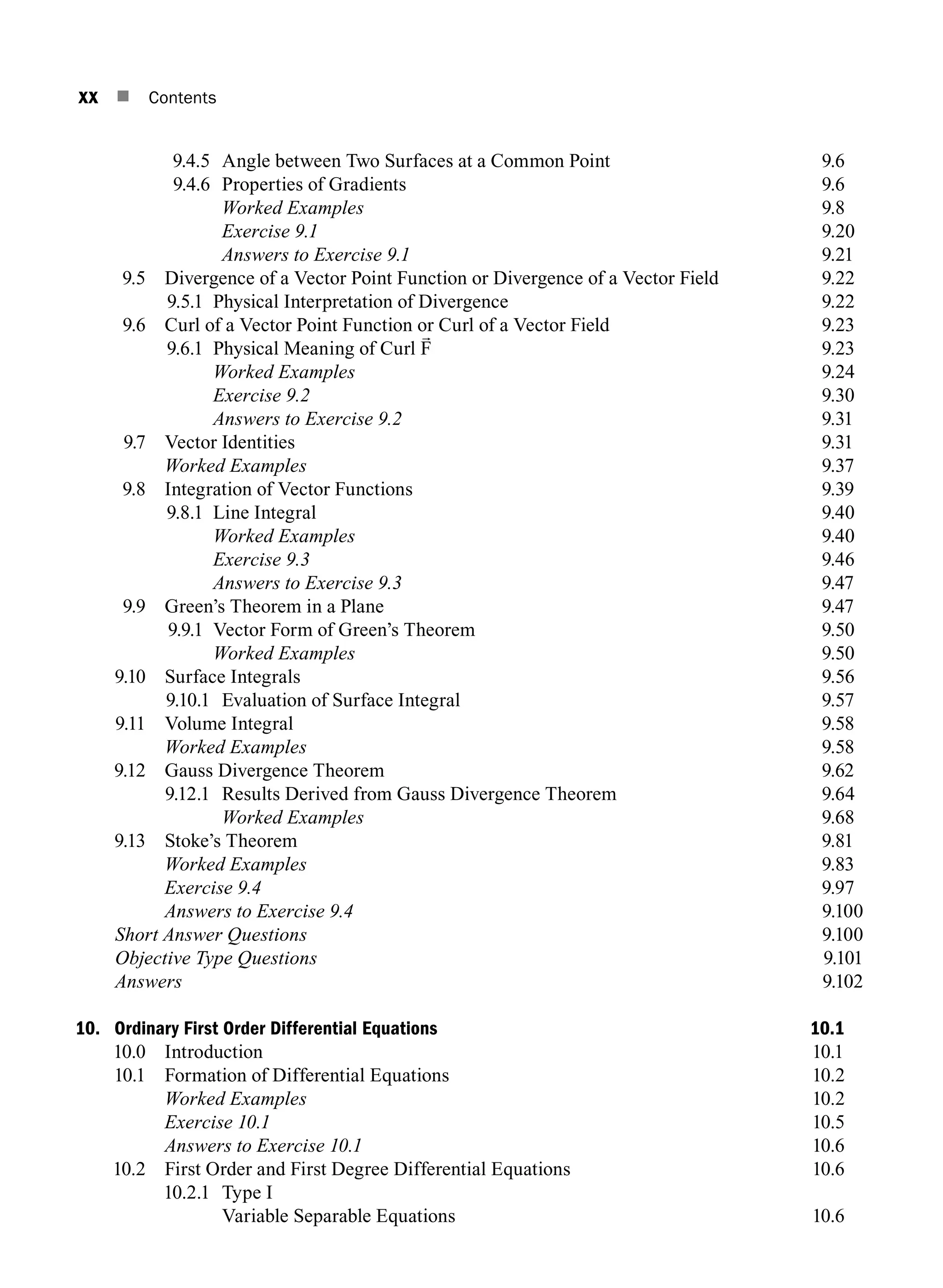

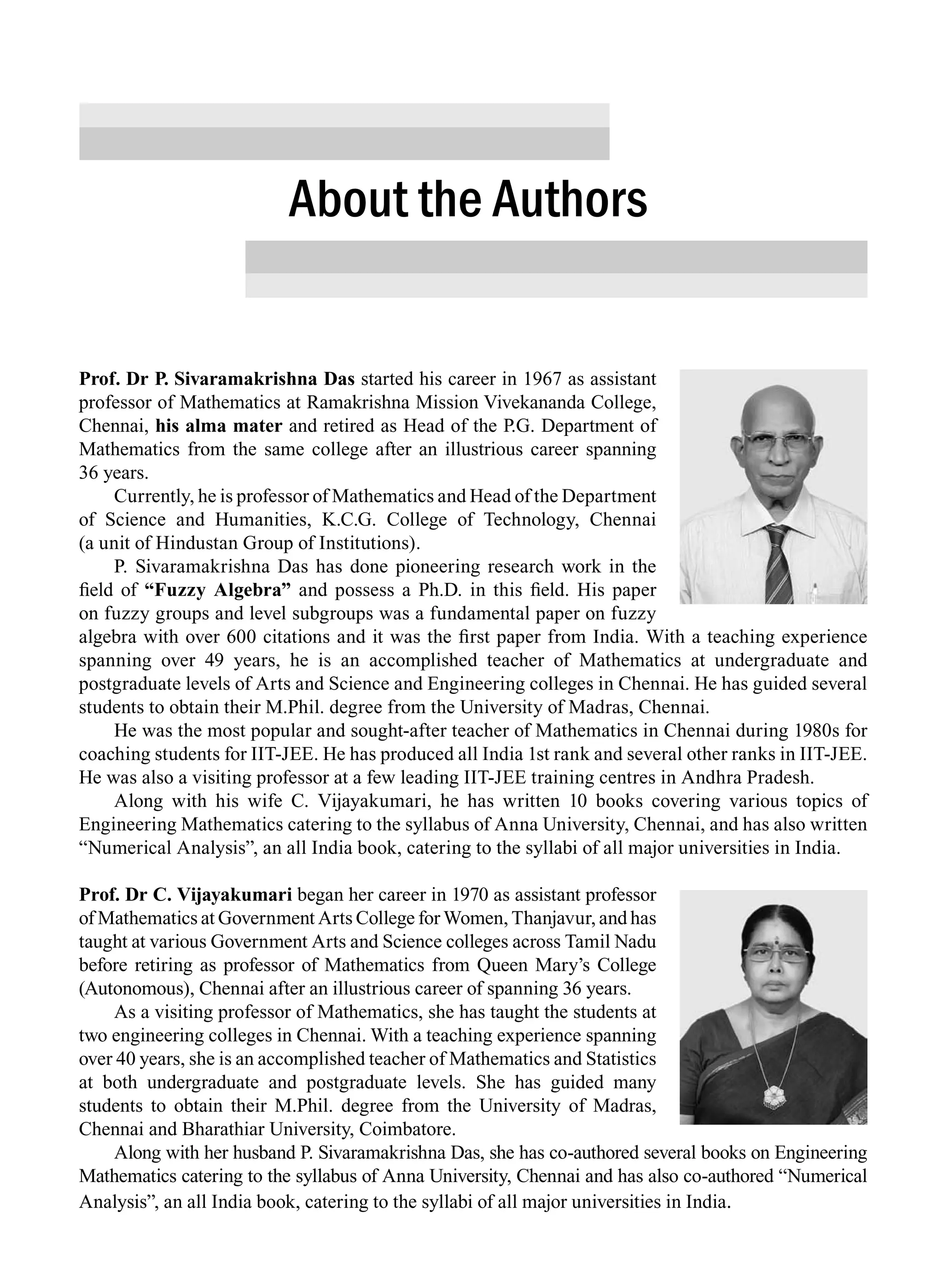

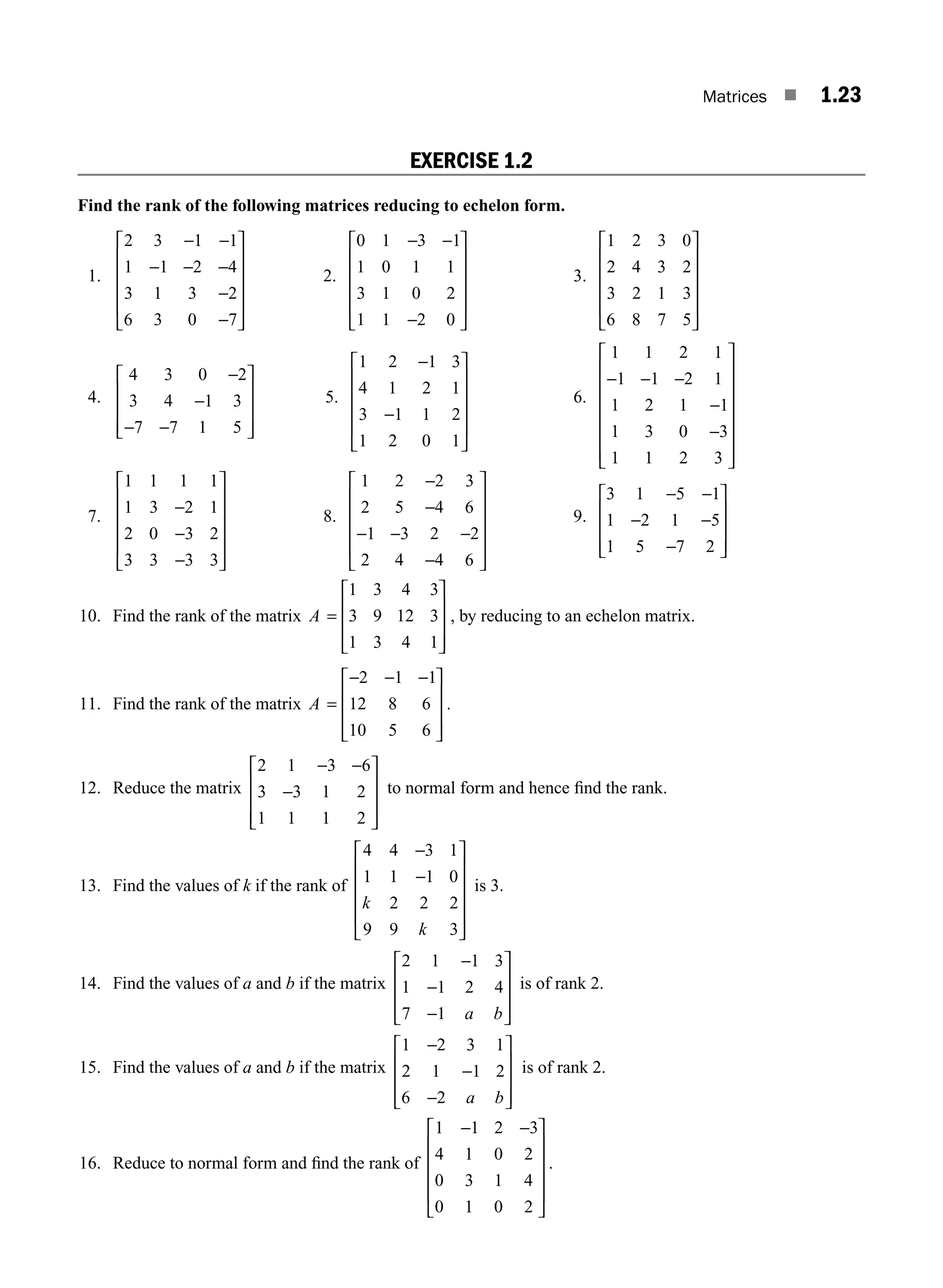

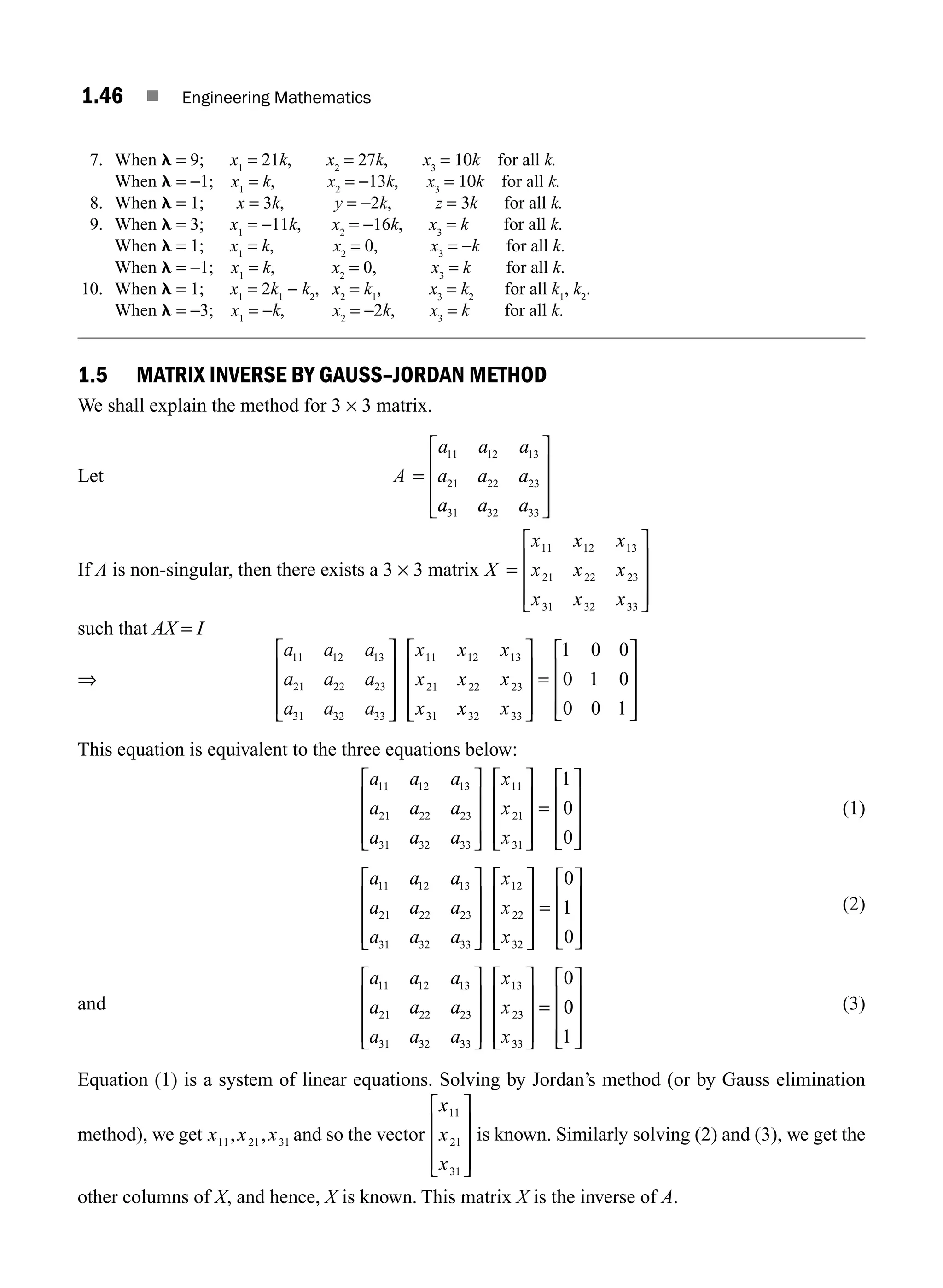

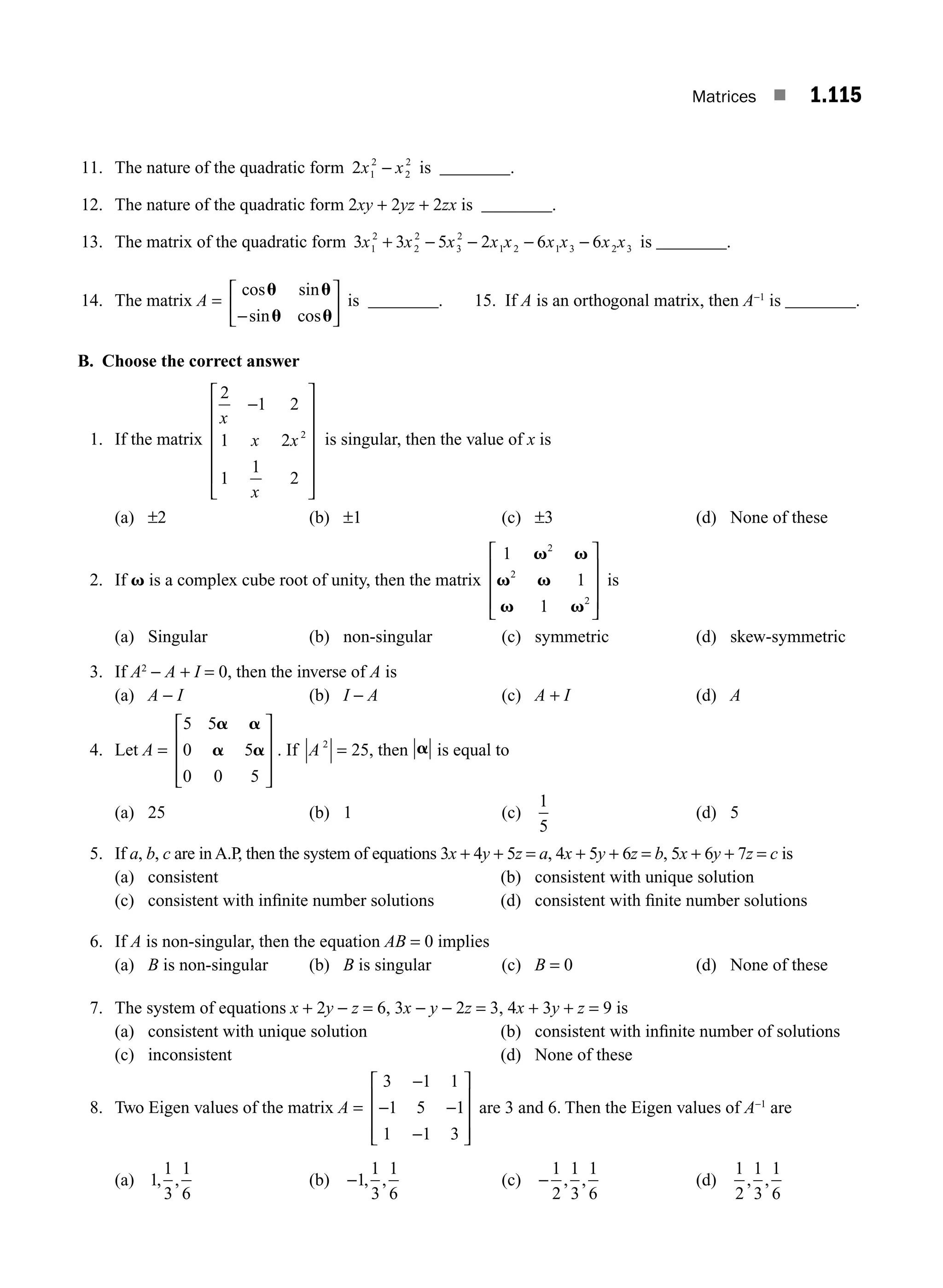

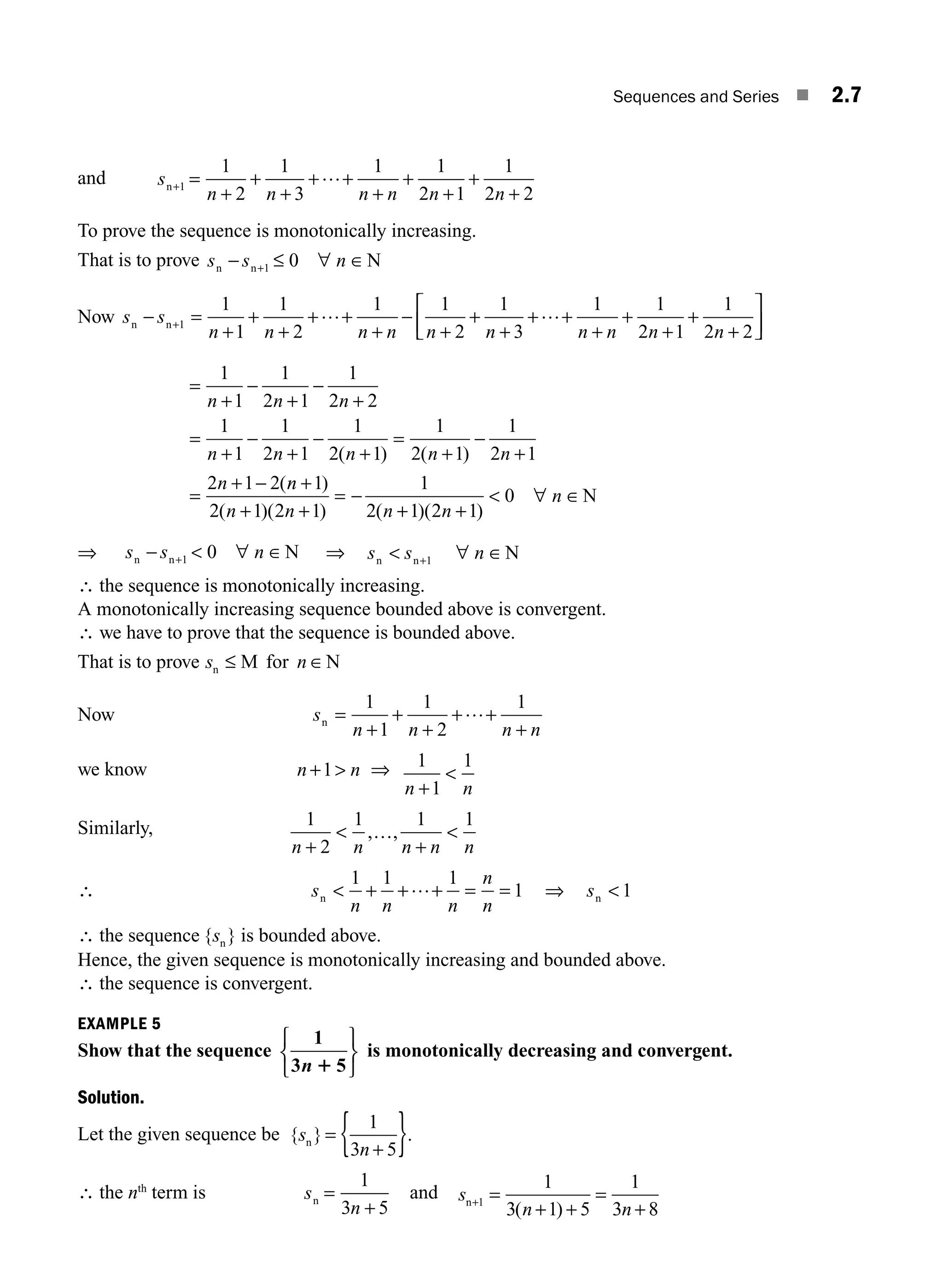

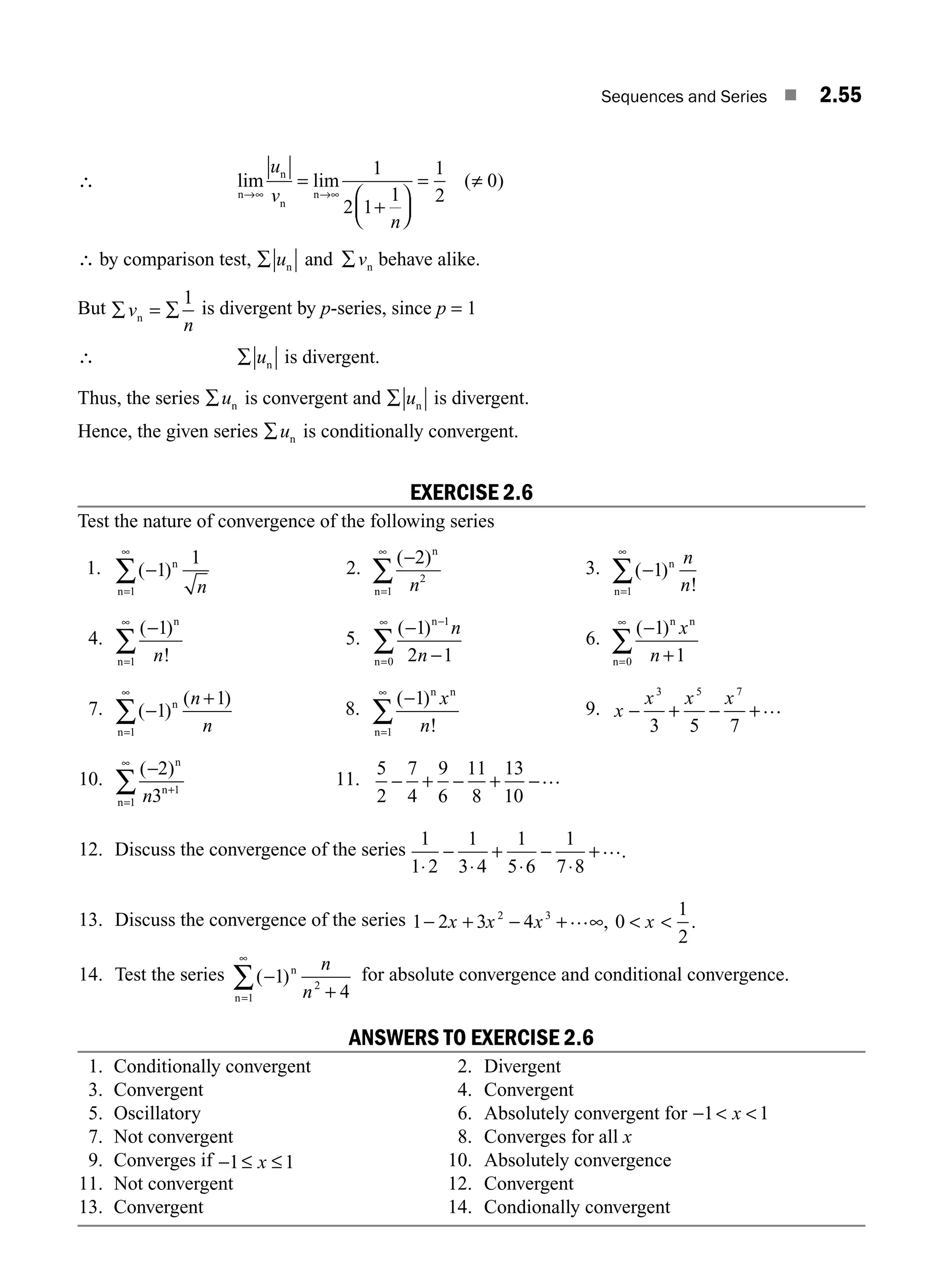

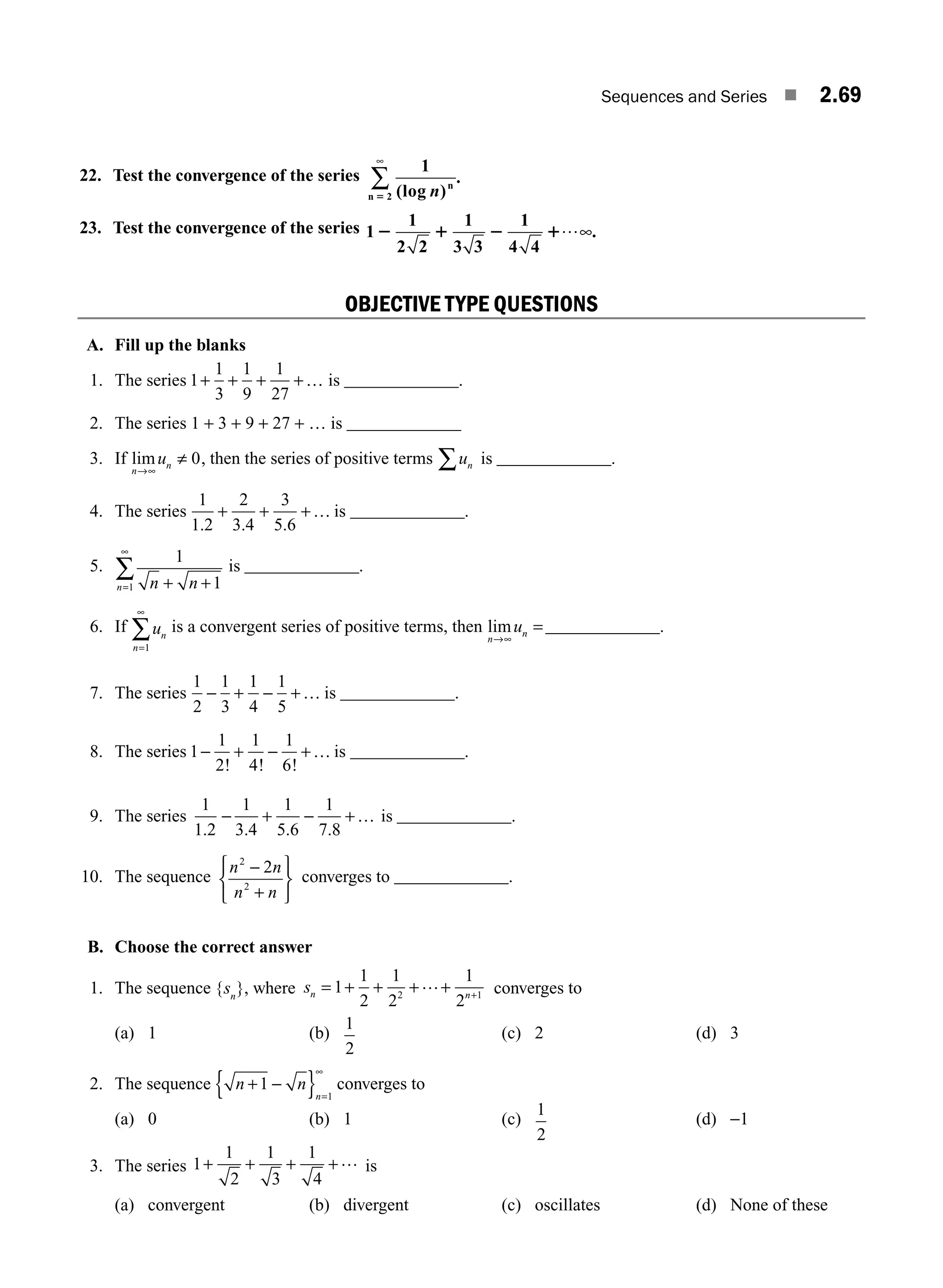

![1.0 INTRODUCTION

The concept of matrices and their basic operations were introduced by the British mathematician

Arthur Cayley in the year 1858. He wondered whether this part of mathematics will ever be used.

However, after 67 years, in 1925, the German physicist Heisenberg used the algebra of matrices in his

revolutionary theory of quantum mechanics. Over the years, the theory of matrices have been found as

an elegant and powerful tool in almost all branches of Science and Engineering like electrical networks,

graph theory, optimisation techniques, system of differential equations, stochastic processes, computer

graphics, etc. Because of the digital computers, usage of matrix methods have become greatly fruitful.

In this chapter, we review some of the basic concepts of matrices. We shall discuss two important

applications of matrices, namely consistency of system of linear equations and the eigen value problems.

1.1 BASIC CONCEPTS

Definition 1.1 Matrix

A rectangular array of mn numbers (real or complex) arranged in m rows (horizontal lines) and

n columns (vertical lines) and enclosed in brackets [ ] is called an m × n matrix.

The numbers in the matrix are called entries or elements of the matrix.

Usually an m × n matrix is written as

A

a a a a

a a a a a

a a a a a

j n

j n

i i i ij in

=

a11 12 13 1 1

21 22 23 2 2

1 2 3

… …

… …

… …

A A A A A

A

A A A

a a a a a

m m m mj mn

1 2 3 … …

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

where aij

is the element lying in the ith

row and jth

column, the first suffix refers to row and the second

suffix refers to column.

The matrix A is briefly written as

A = [aij

]m × n

, i = 1, 2, 3, …, m, j = 1, 2, 3, …, n

If all the entries are real, then the matrix A is called a real matrix.

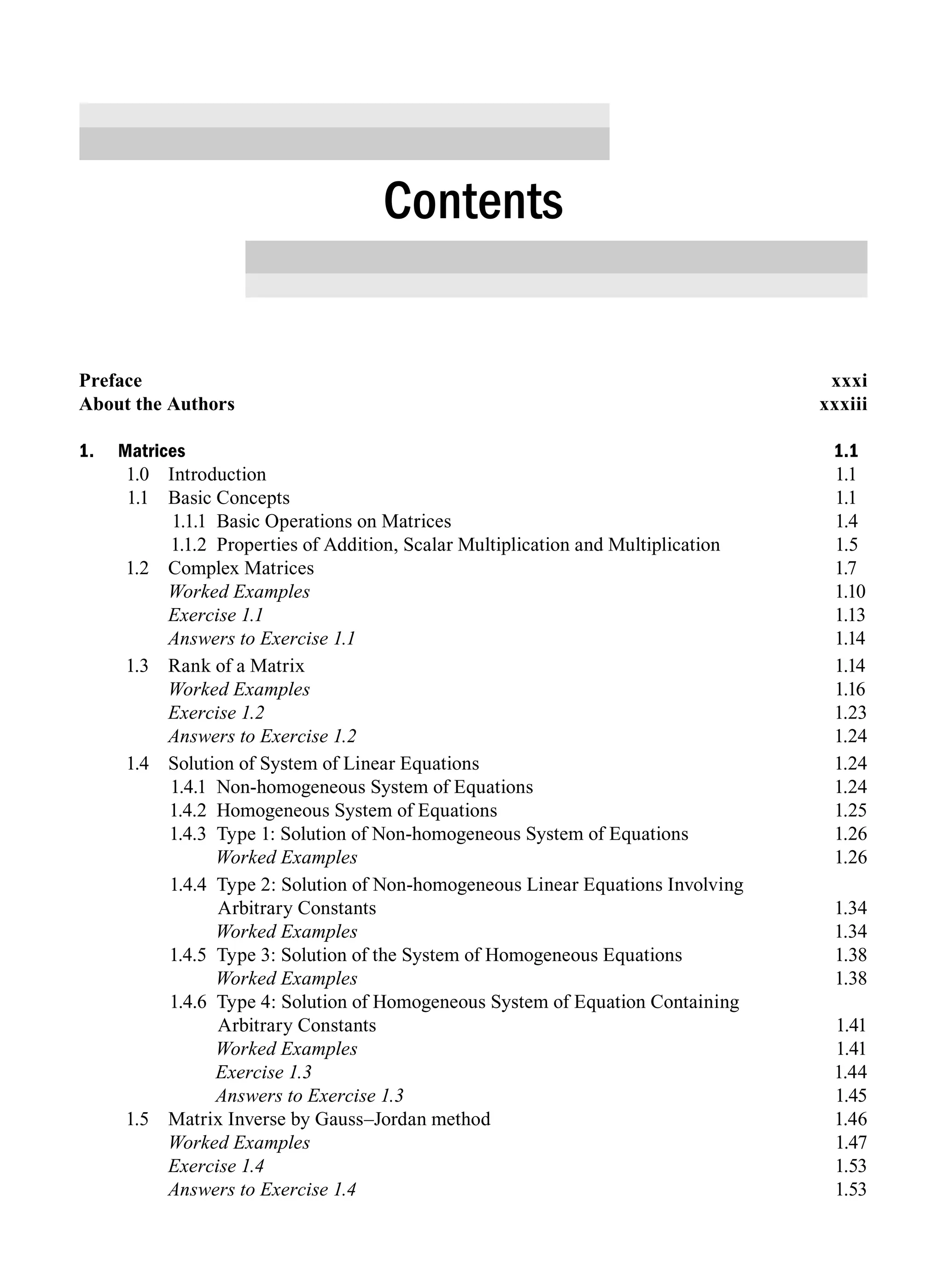

Definition 1.2 Square Matrix

In a matrix, if the number of rows = number of columns = n, then it is called a square matrix of order n.

If A is a square matrix of order n, then A = [aij

]n × n

, i = 1, 2, 3, …, n; j = 1, 2, 3, …, n.

Definition 1.3 Row Matrix

A matrix with only one row is called a row matrix.

1

Matrices

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 1 5/30/2016 4:34:37 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-38-2048.jpg)

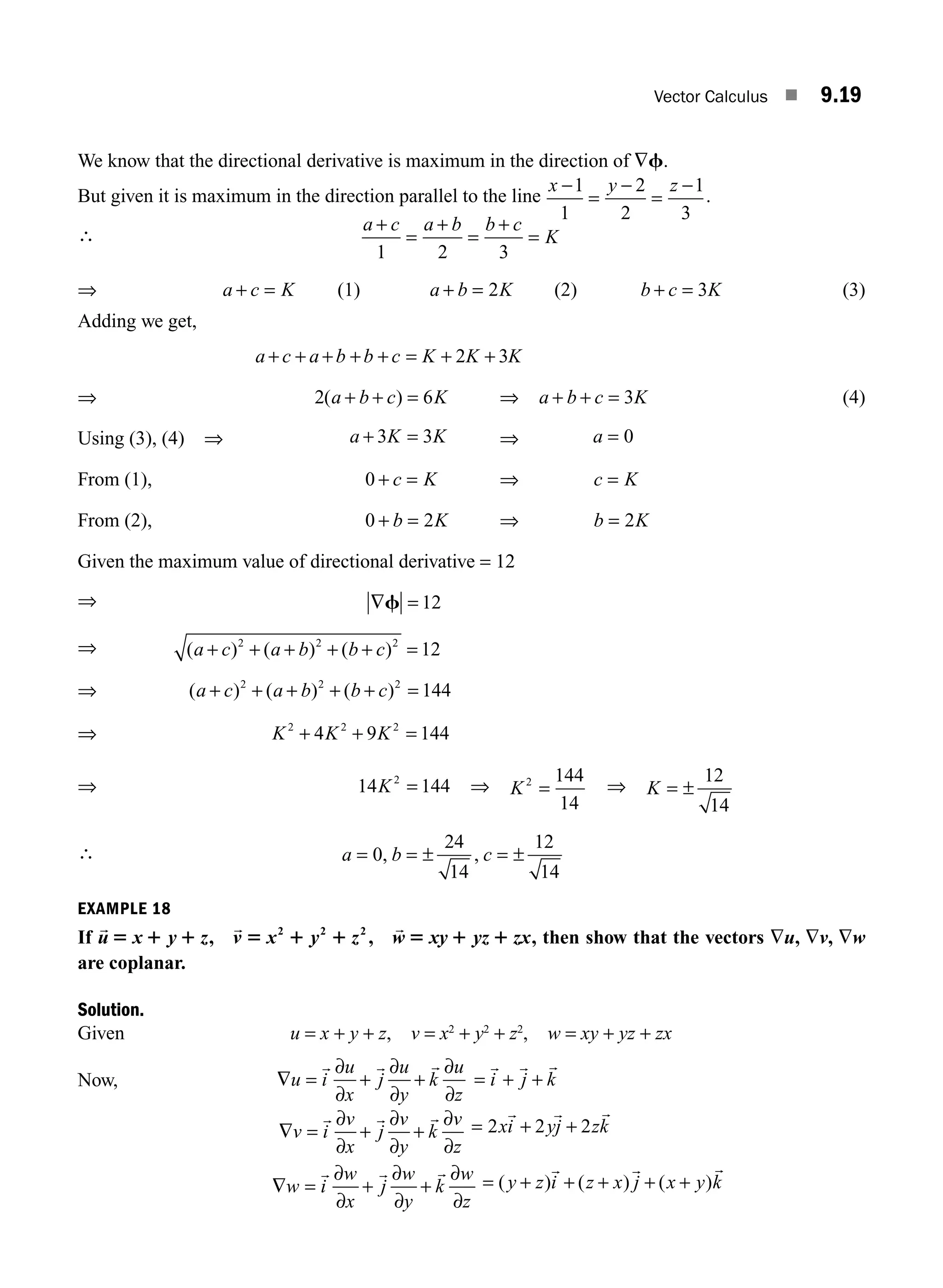

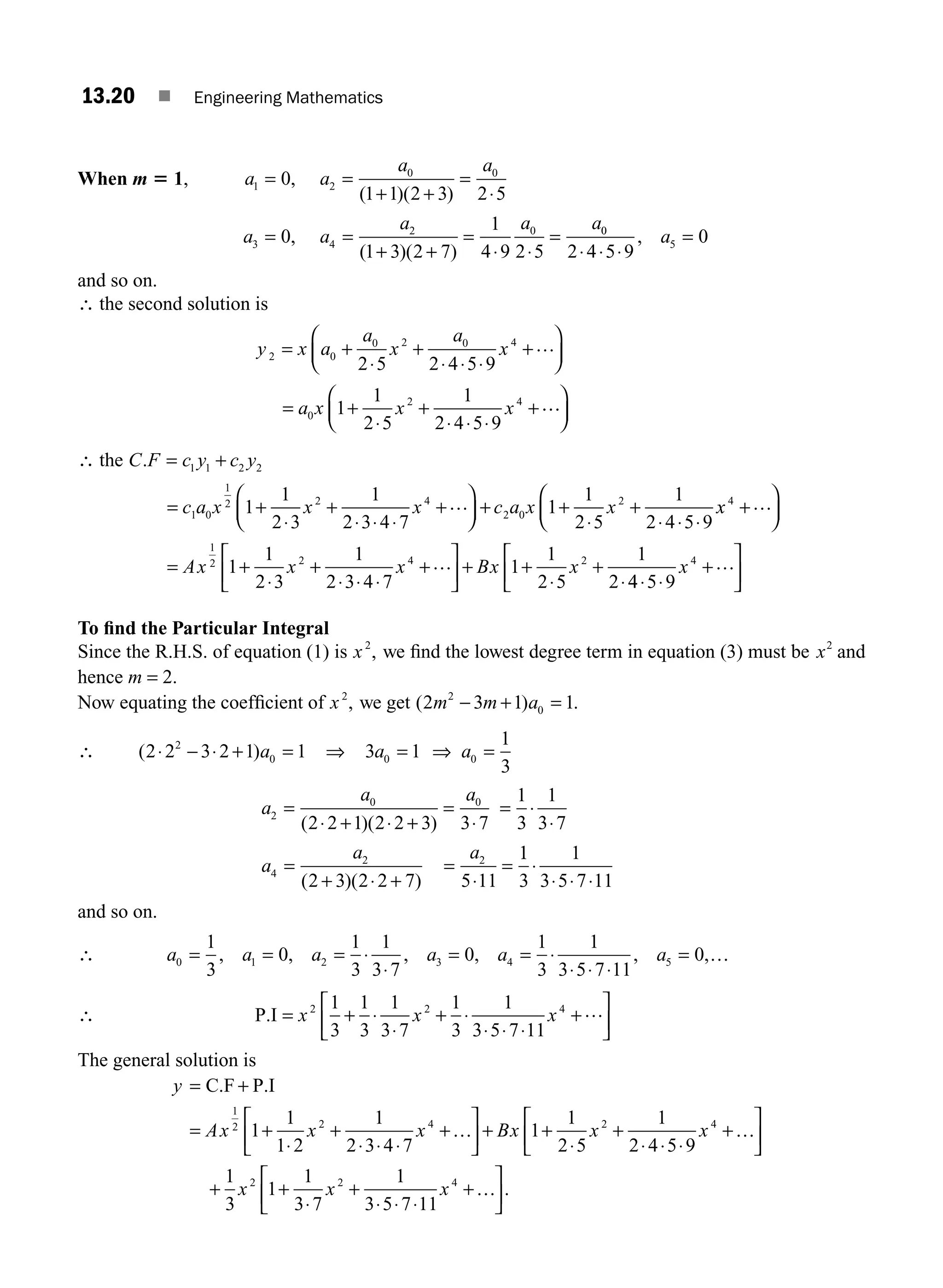

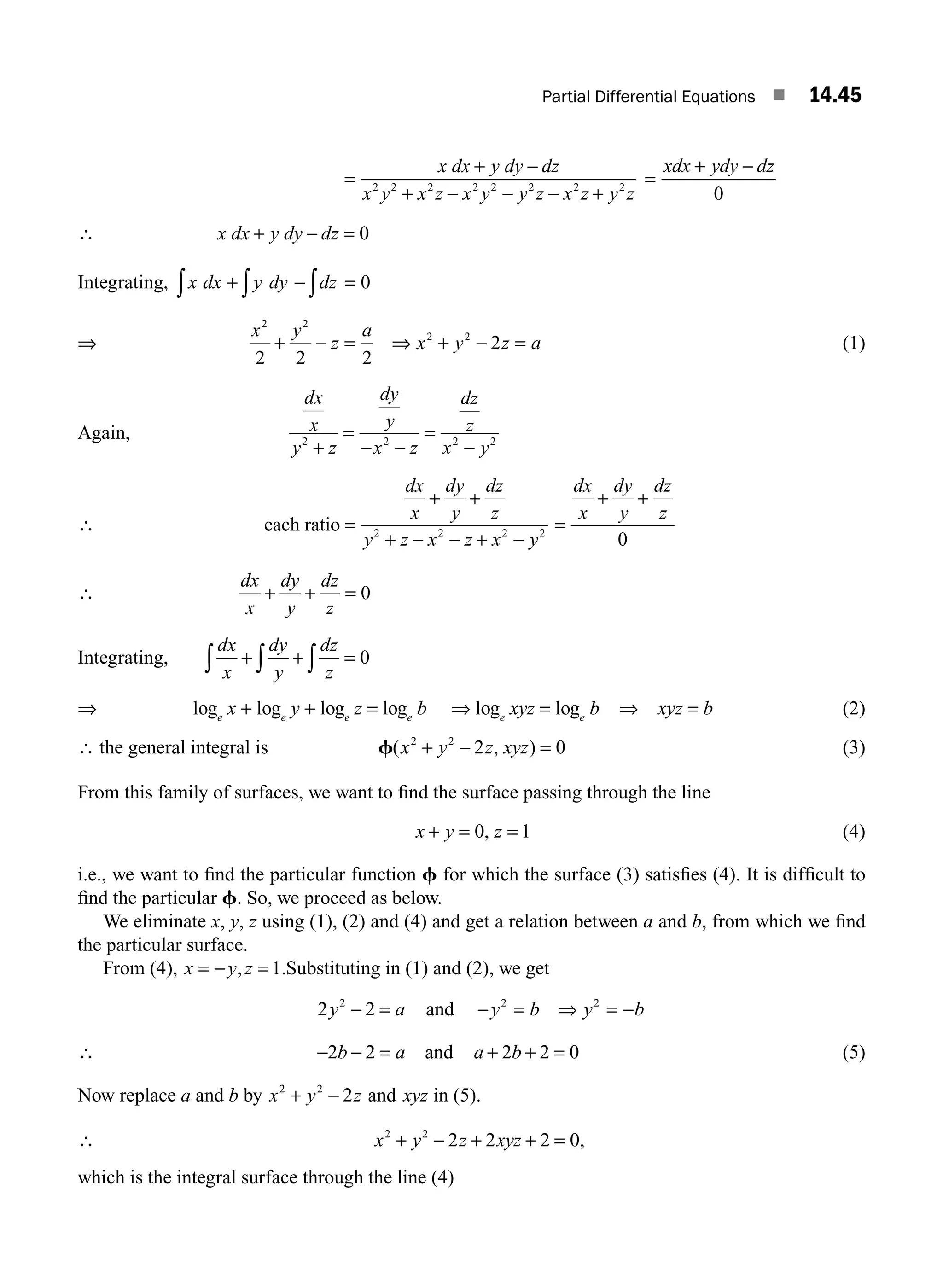

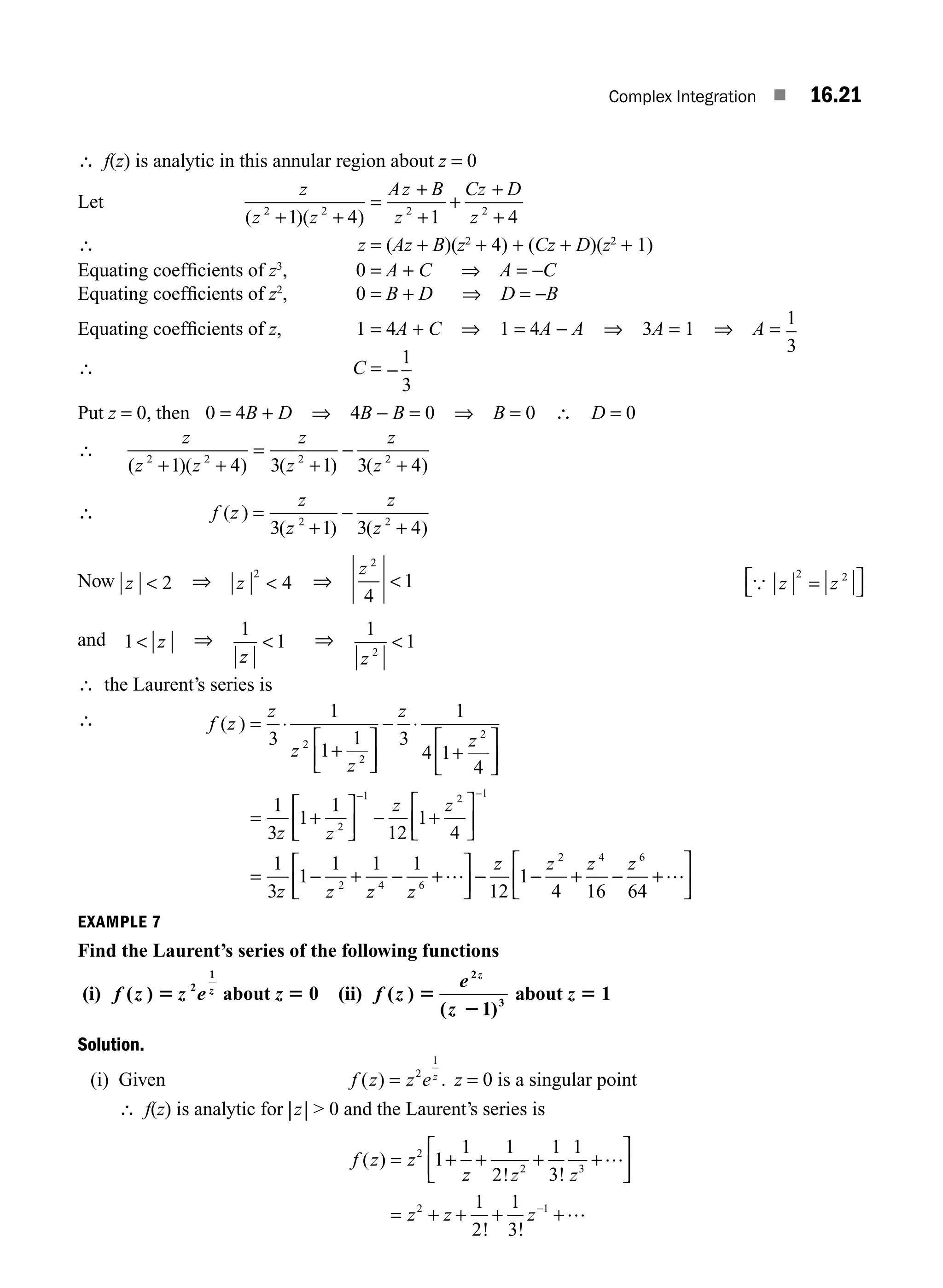

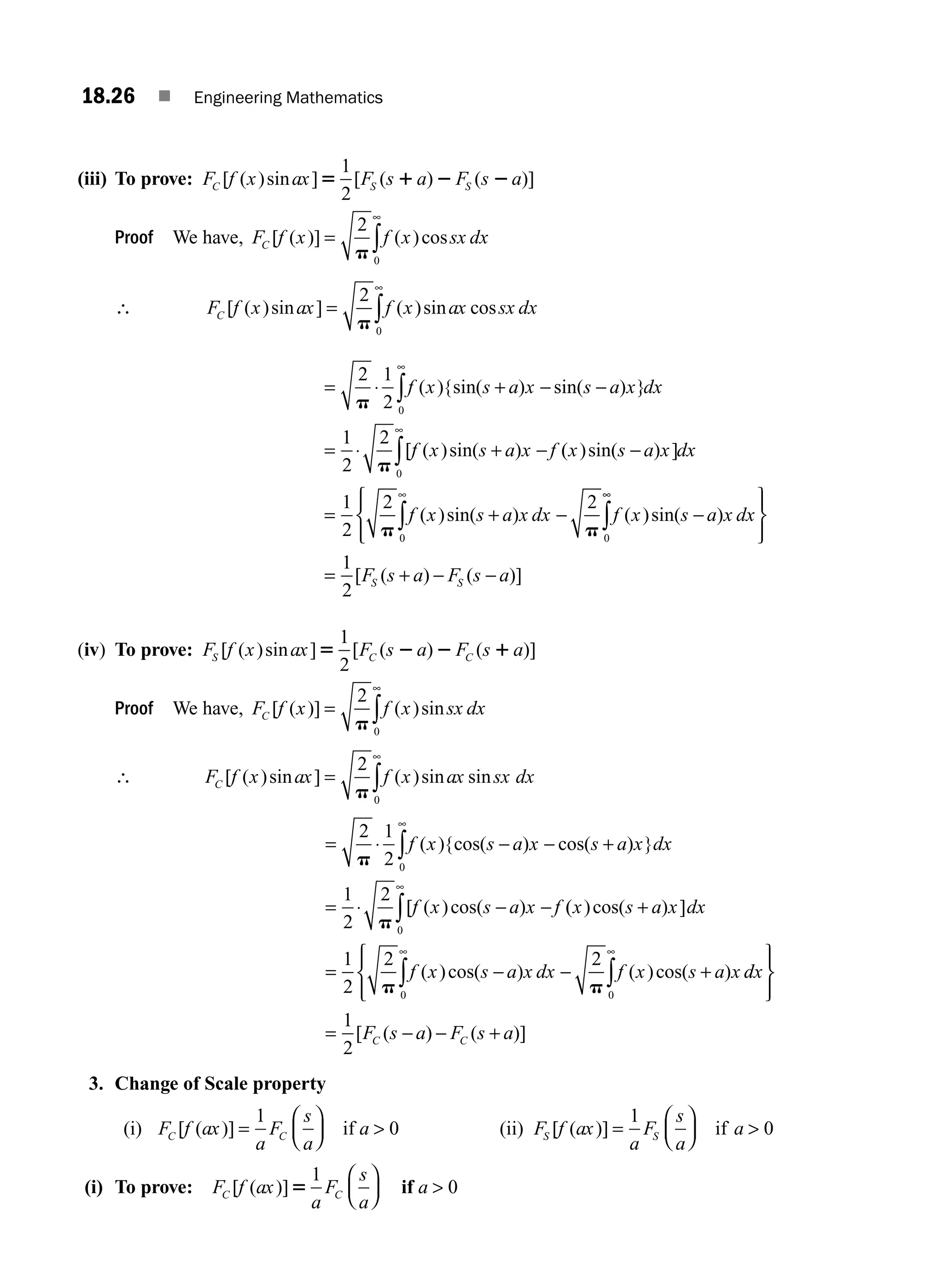

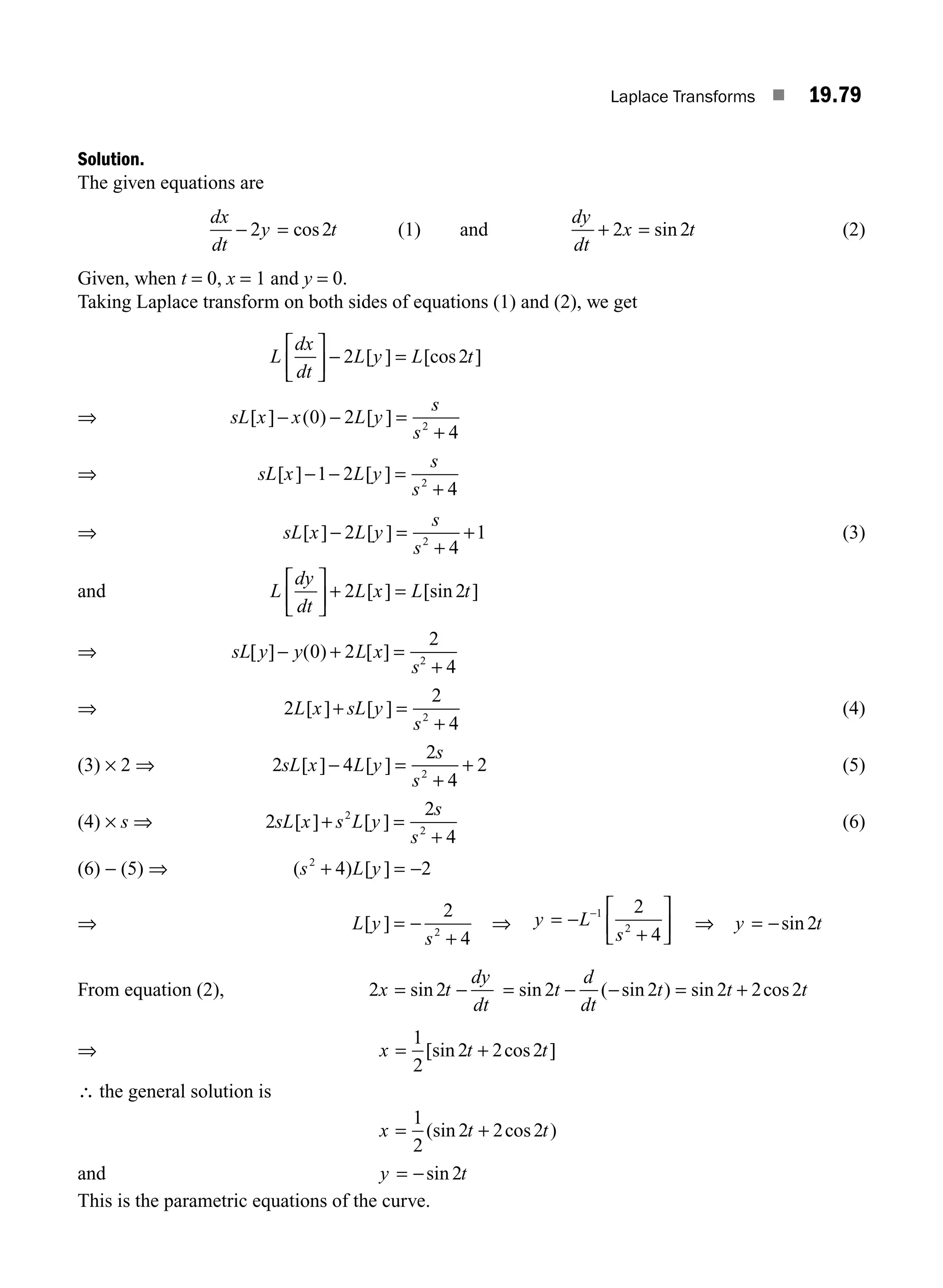

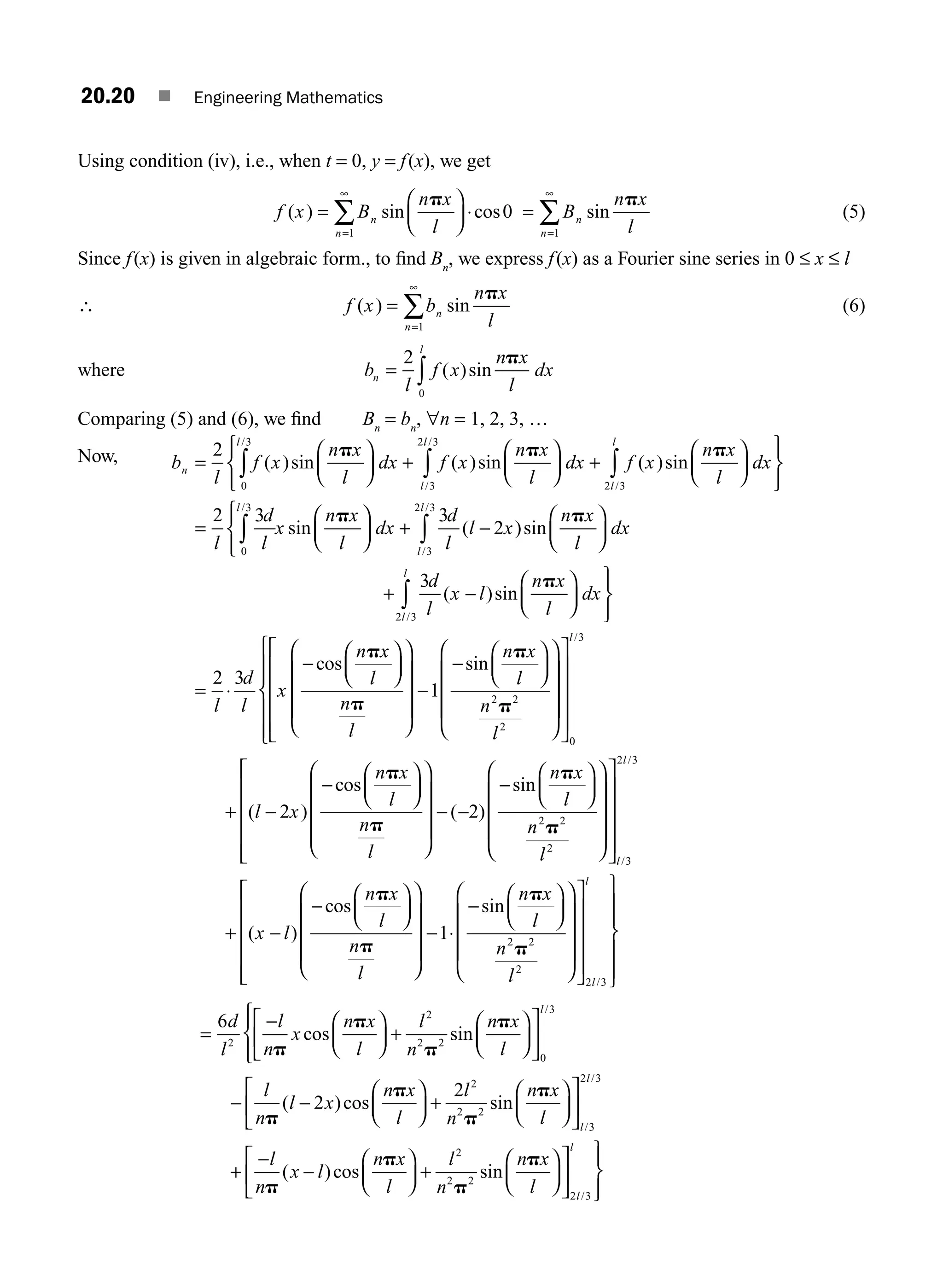

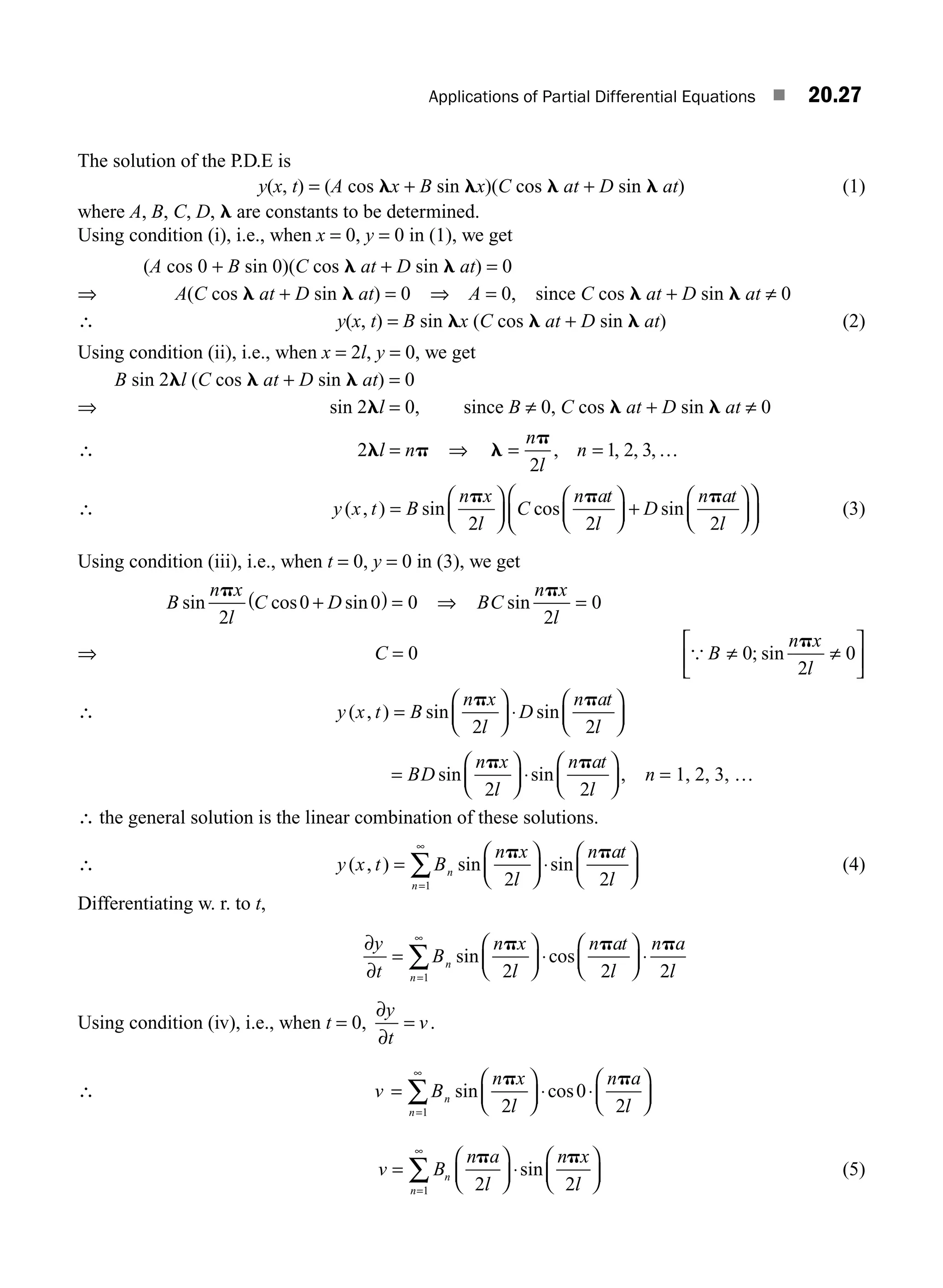

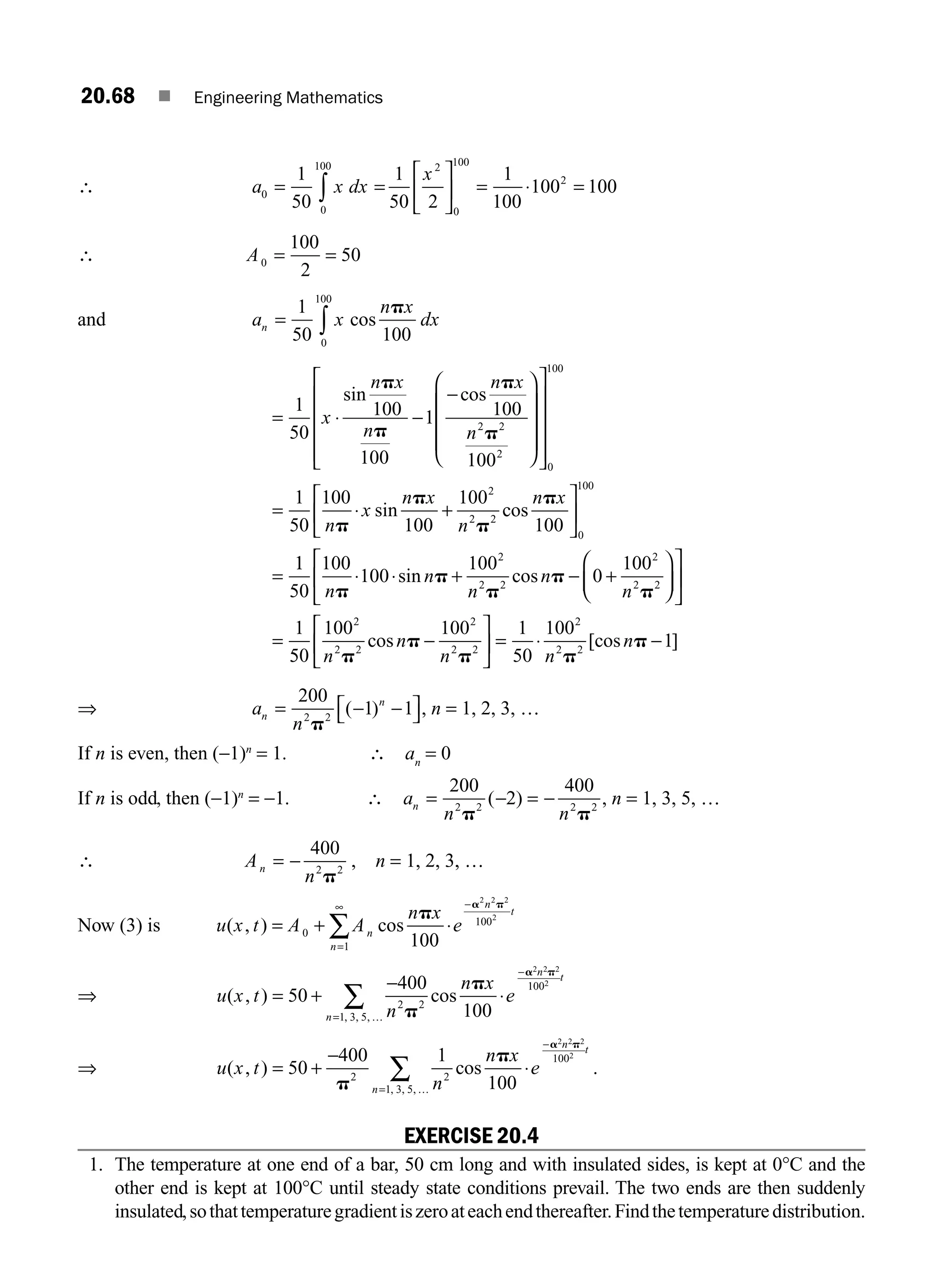

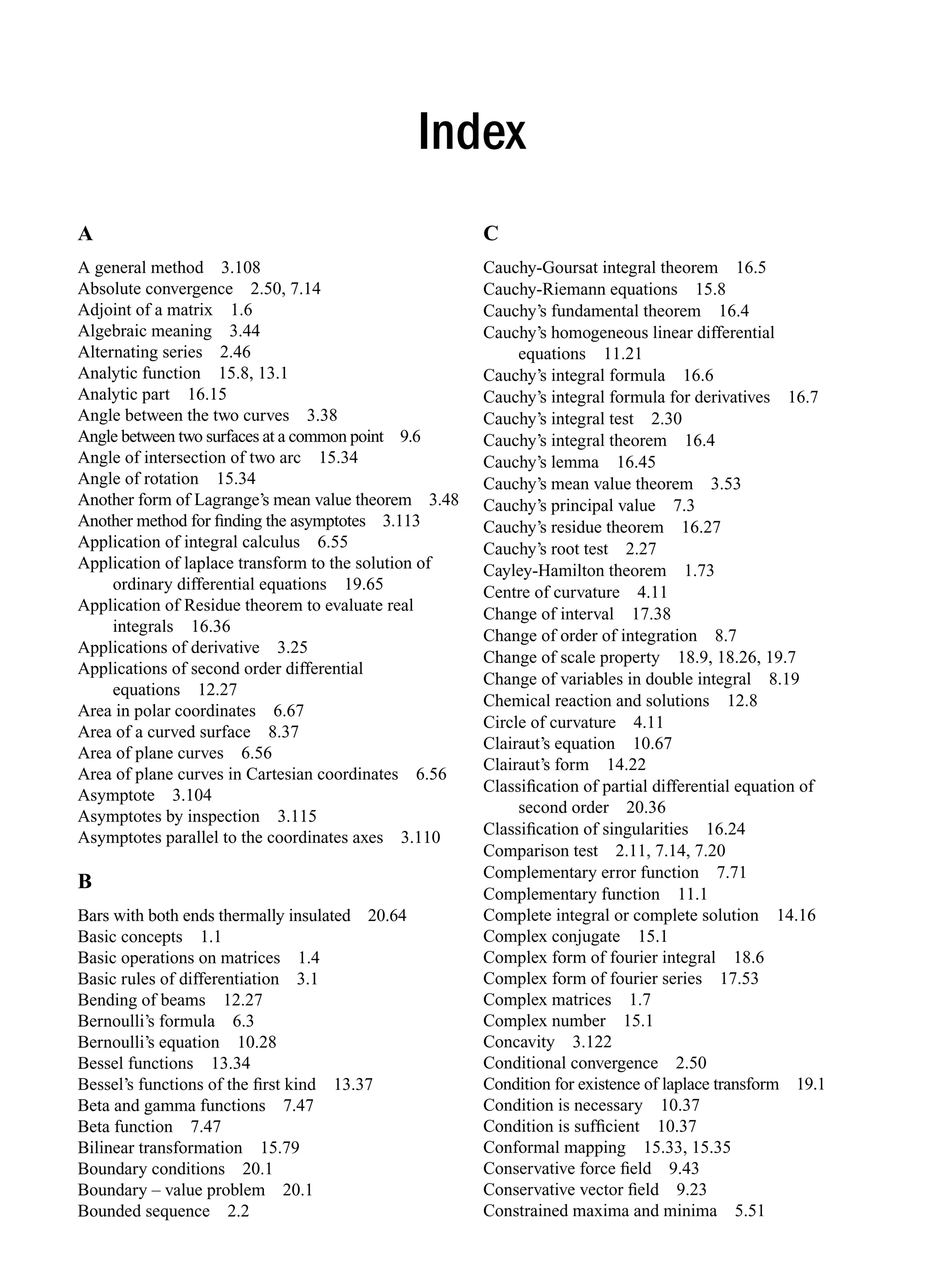

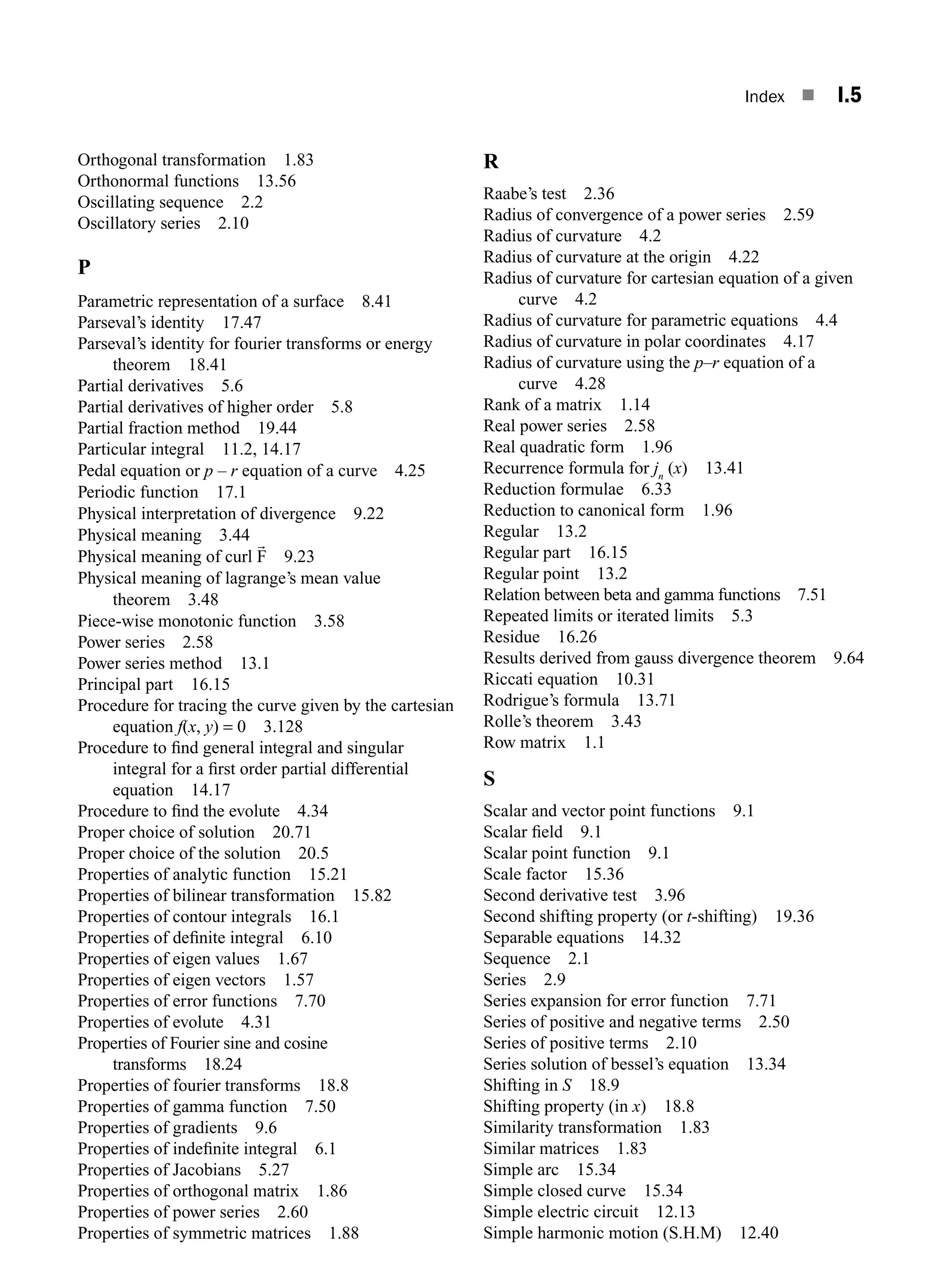

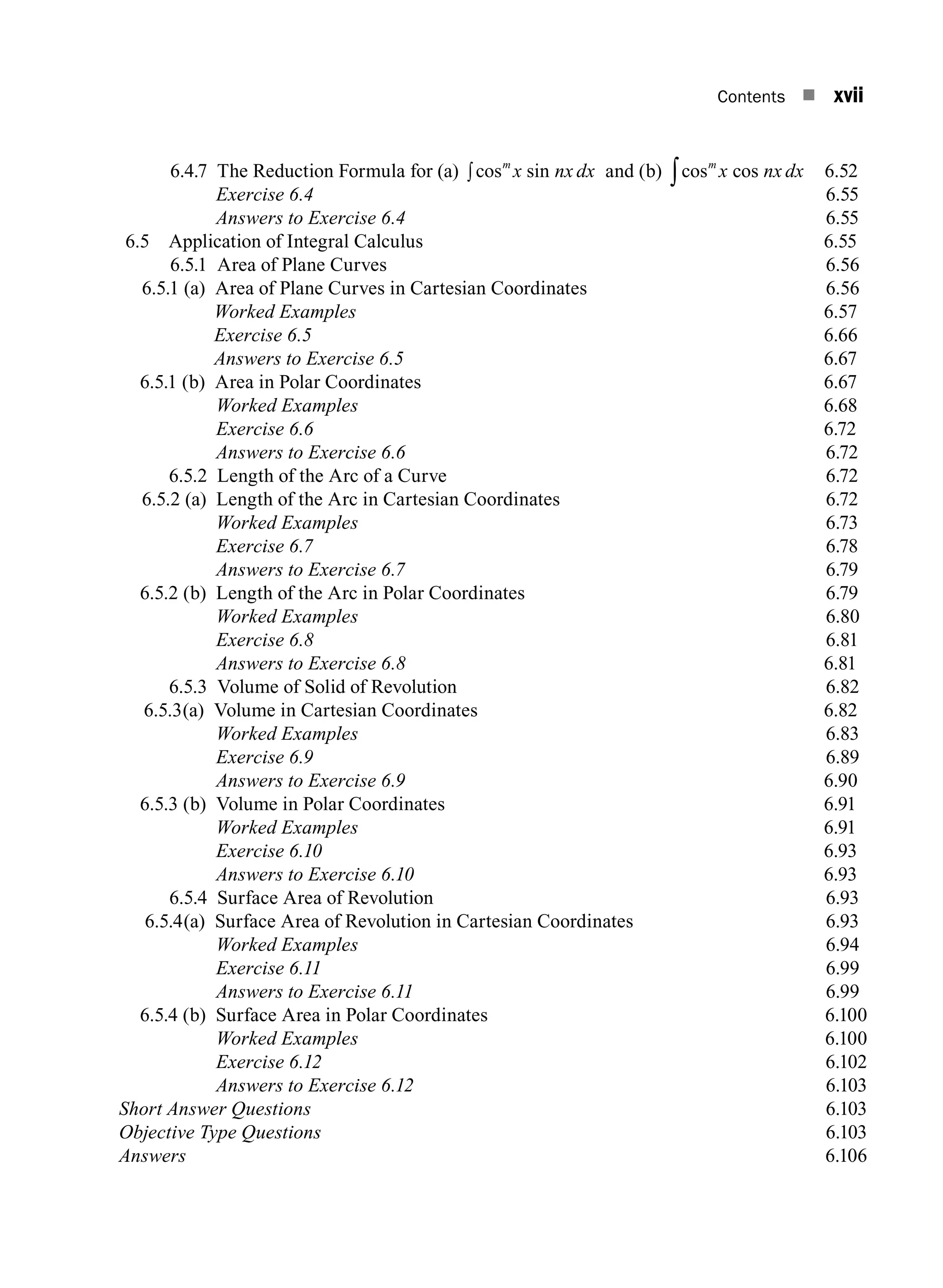

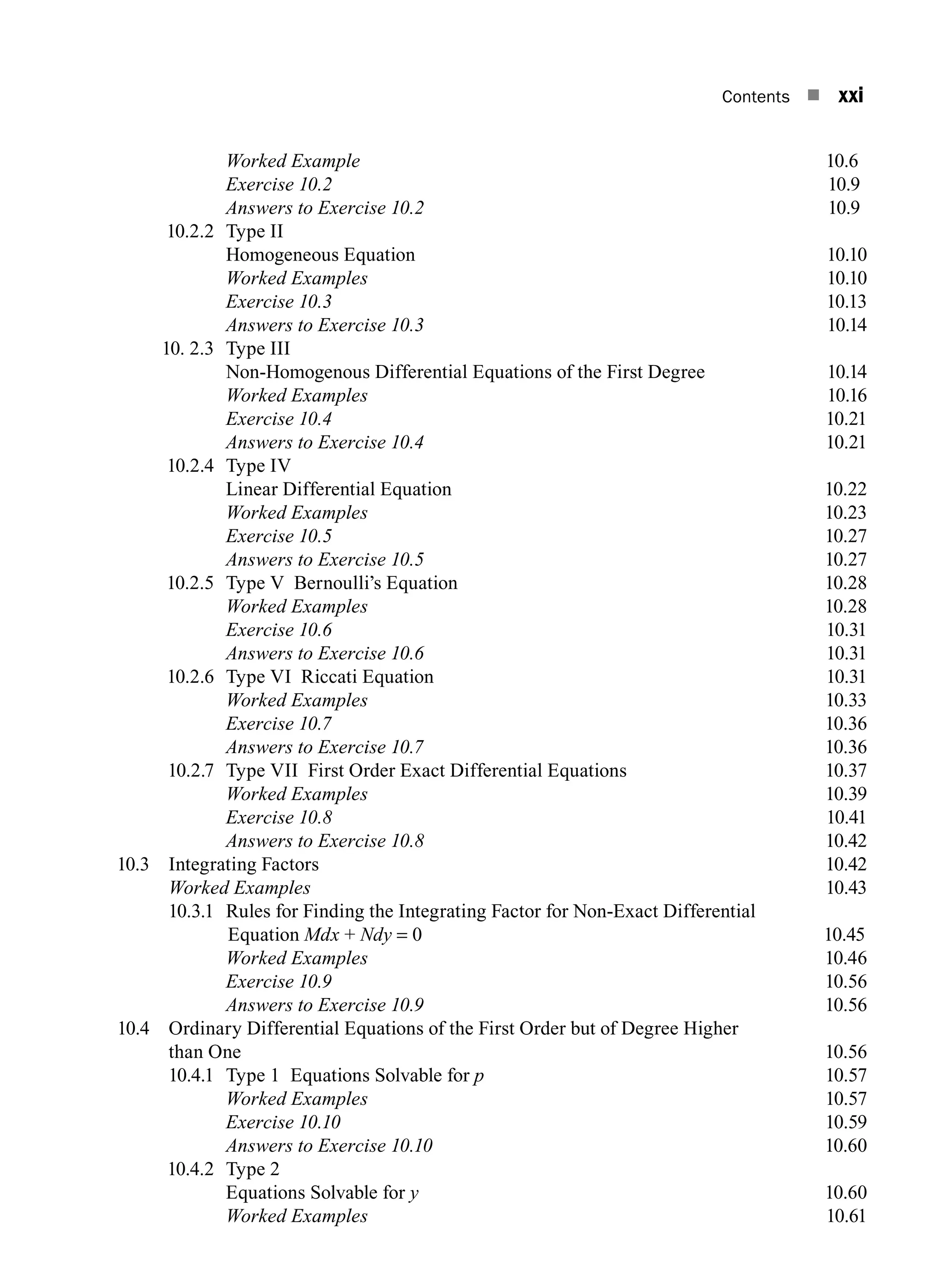

![1.2 ■ Engineering Mathematics

EXAMPLE 1.1

Let A = [a11

a12

a13

… a1n

]. It is a row matrix with n columns. So, it is of type 1 × n.

EXAMPLE 1.2

Let A = [1, 2, 3, 4]. It is a row matrix with 4 columns. So, it is a row matrix of type 1 × 4.

Definition1.4 Column Matrix

A matrix with only one column is called a column matrix.

EXAMPLE 1.3

Let A

a

a

a

an

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

11

21

31

1

:

It is a column matrix with n rows. So, it is of type n × 1.

EXAMPLE 1.4

Let A = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1

0

2

1

3

It is a column matrix with 5 rows. So, it is of type 5 × 1.

Definition 1.5 Diagonal Matrix

A square matrix A = [aij

] with all entries aij

= 0 when i ≠ j is is called a diagonal matrix.

In other words a square matrix in which all the off diagonal elements are zero is called a diagonal

matrix.

EXAMPLE 1.5

(1) A

a

ann

=

…

…

…

11 0 0 0

0 0

0 0 0

0 22

a

: : :

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

is a diagonal matrix of order n.

(2) A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 0 0

0 3 0

0 0 4

is a diagonal matrix of order 3.

(3) A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 0 0 0

0 2 0 0

0 0 3 0

0 0 0 0

is a diagonal matrix of order 4.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 2 5/30/2016 4:34:38 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-39-2048.jpg)

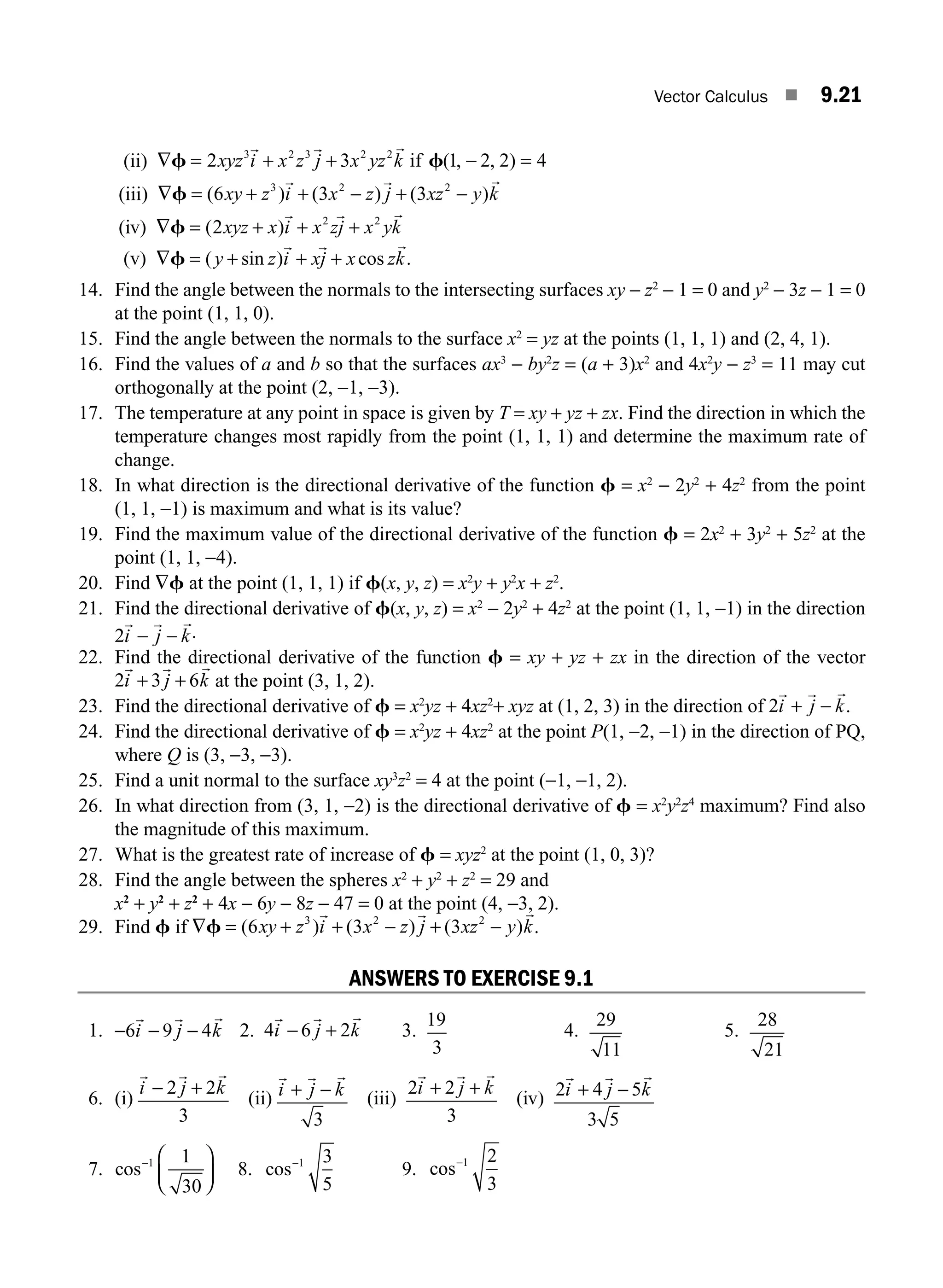

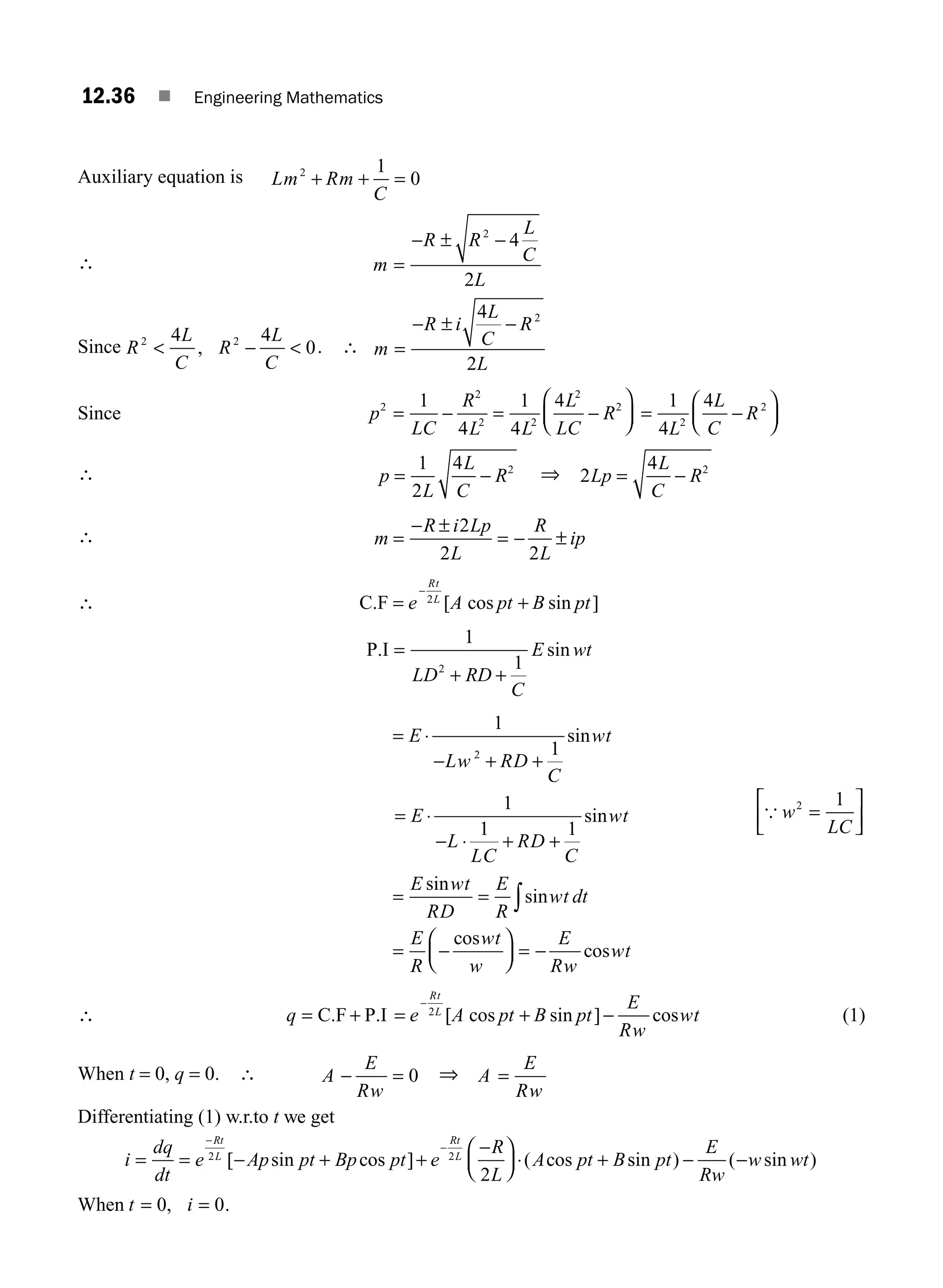

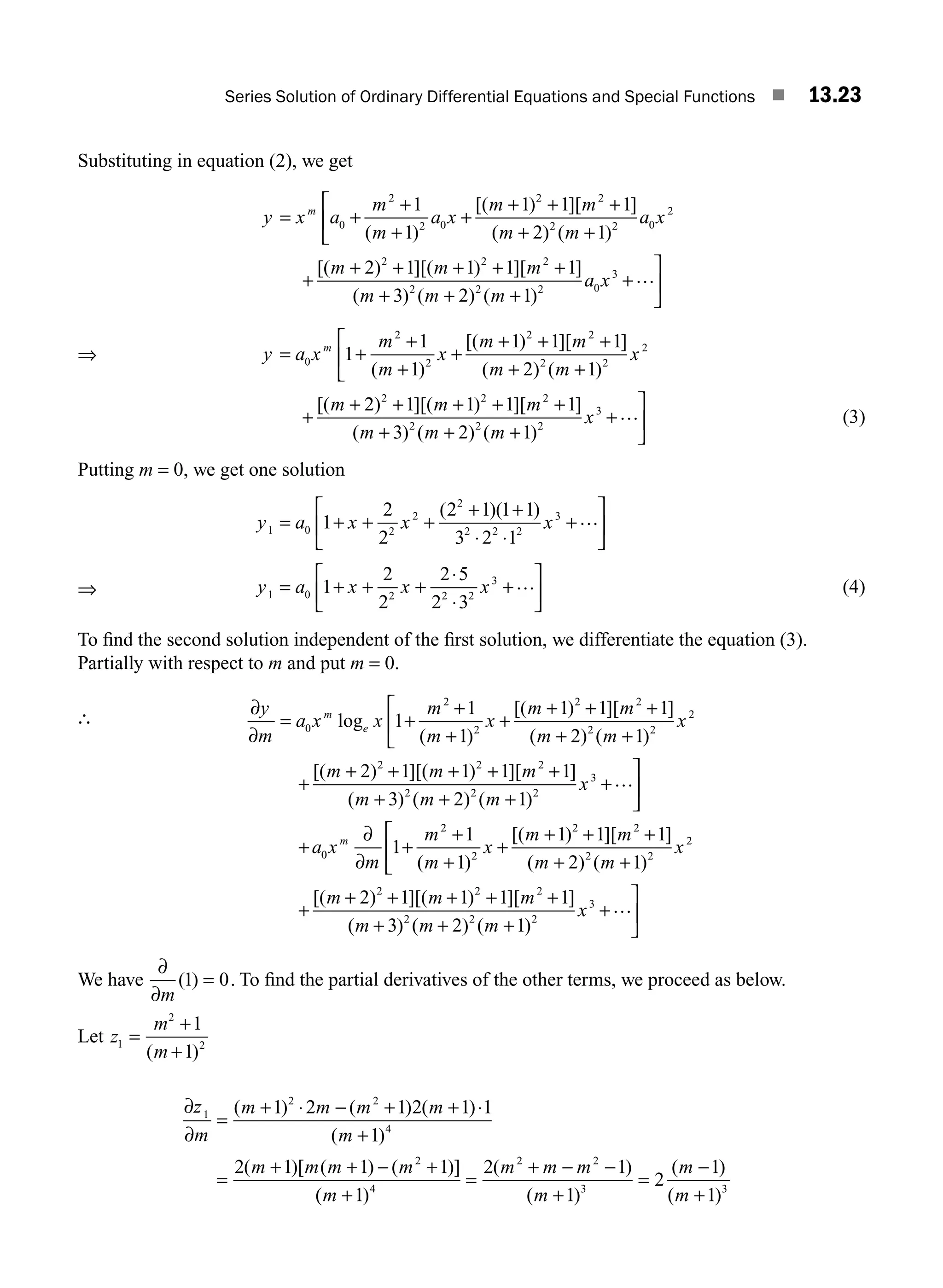

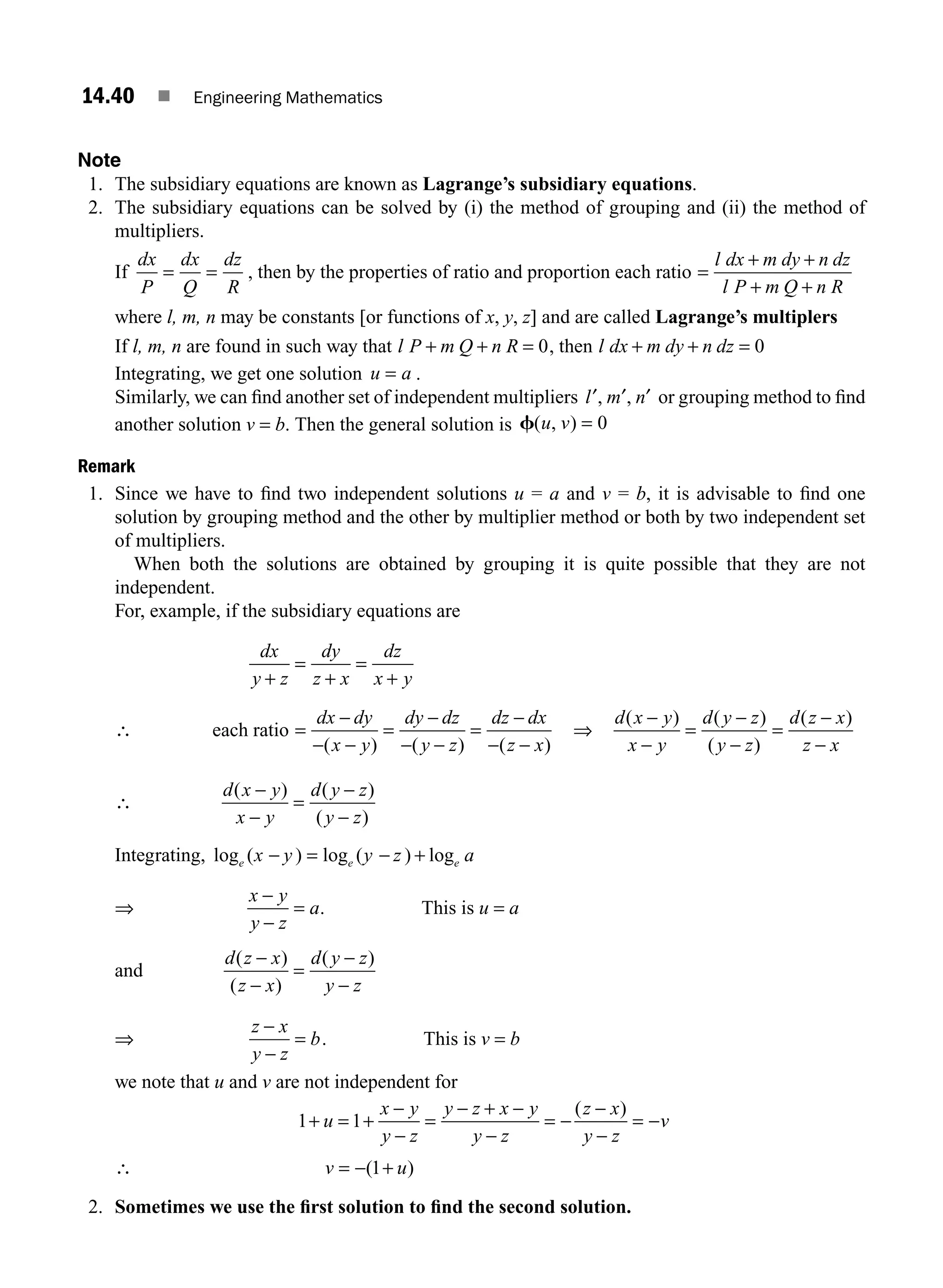

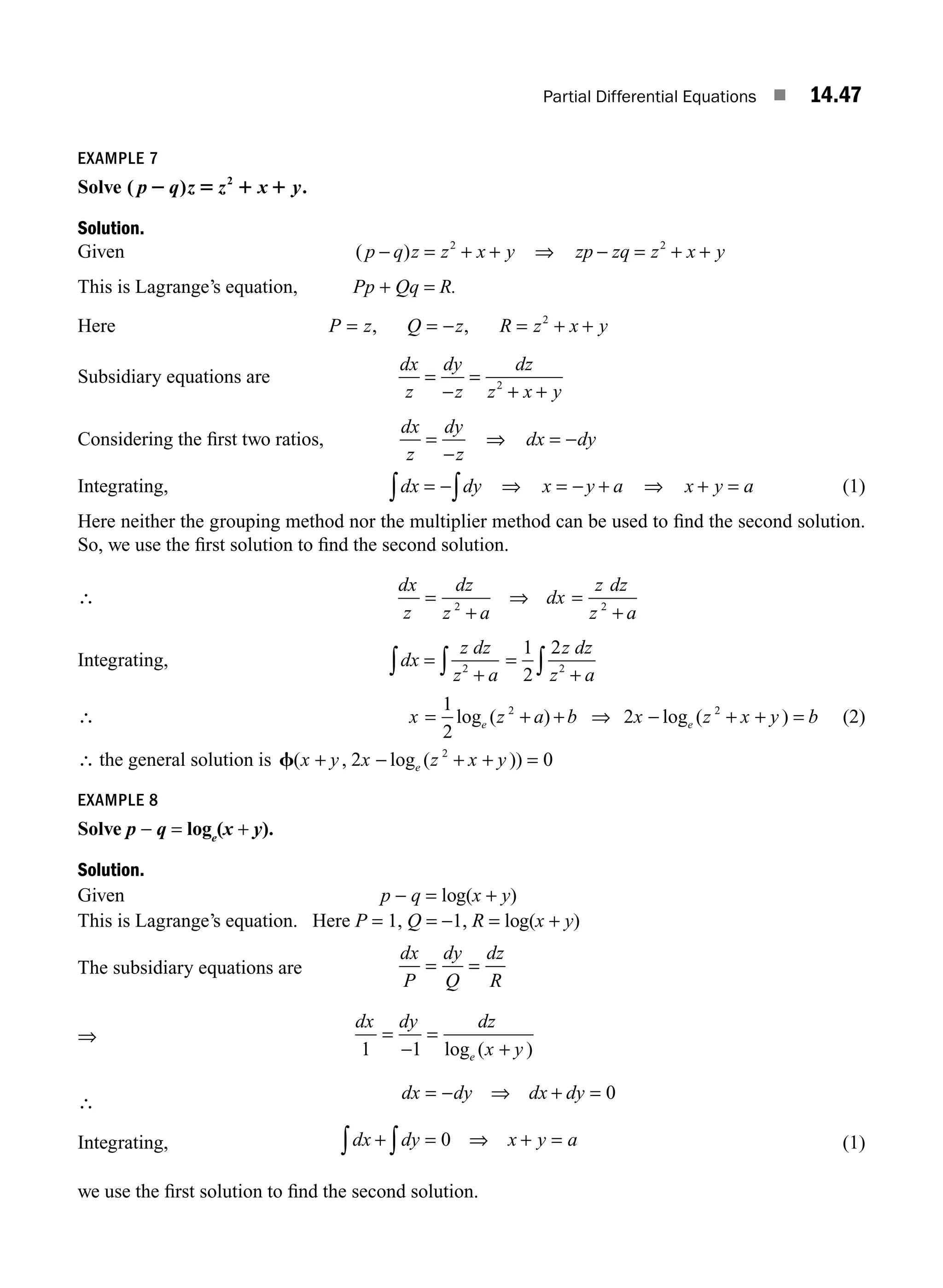

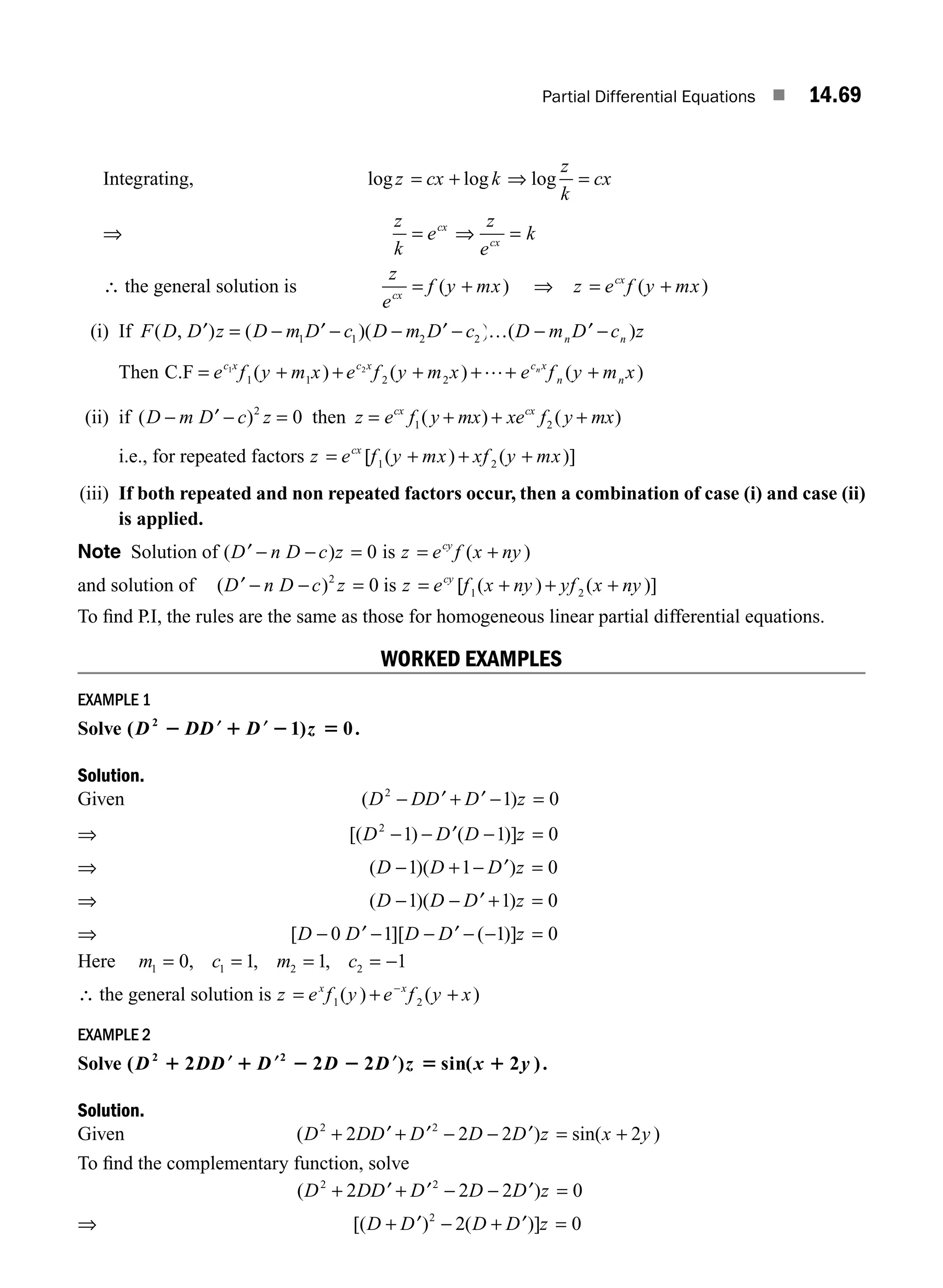

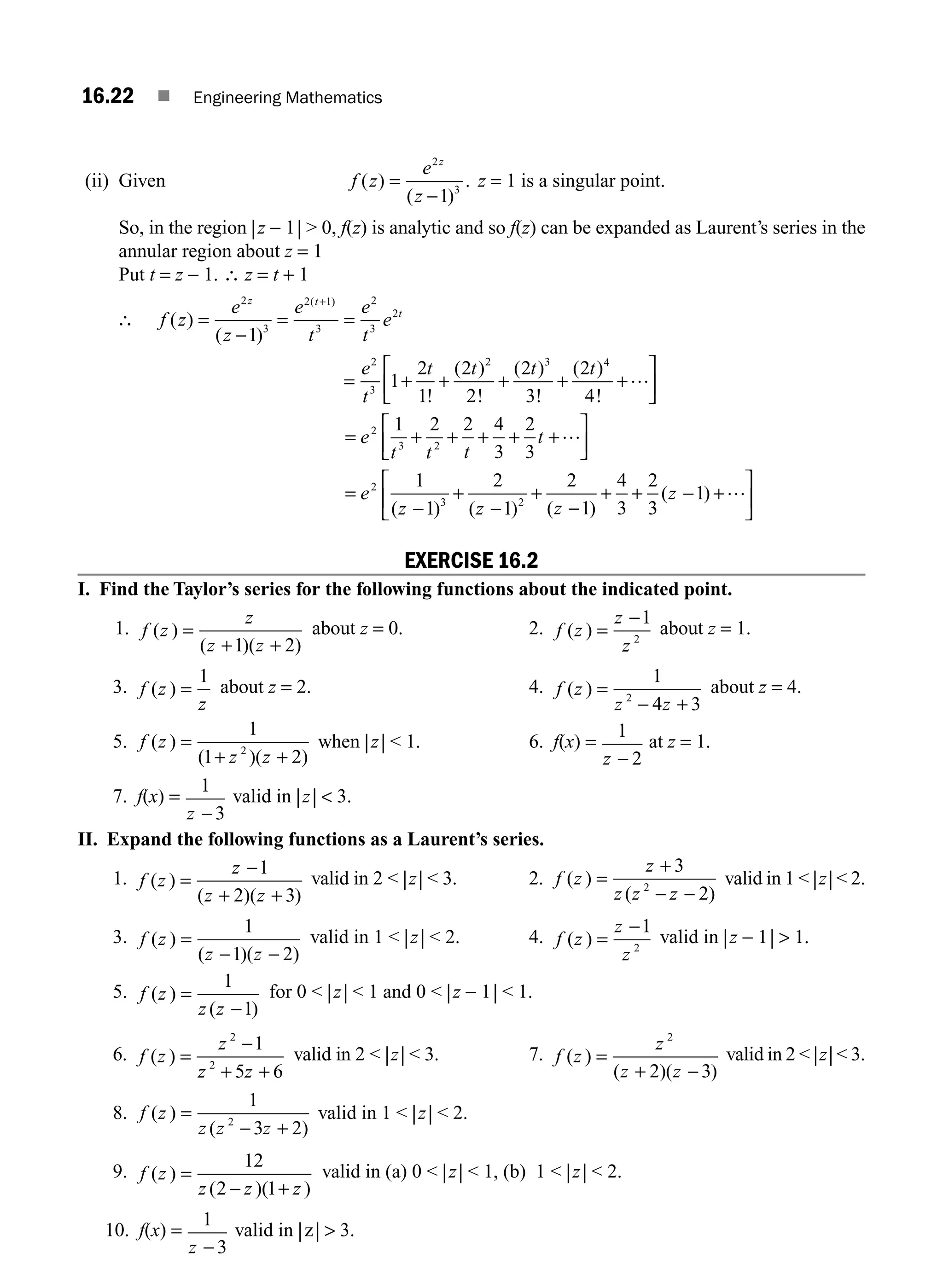

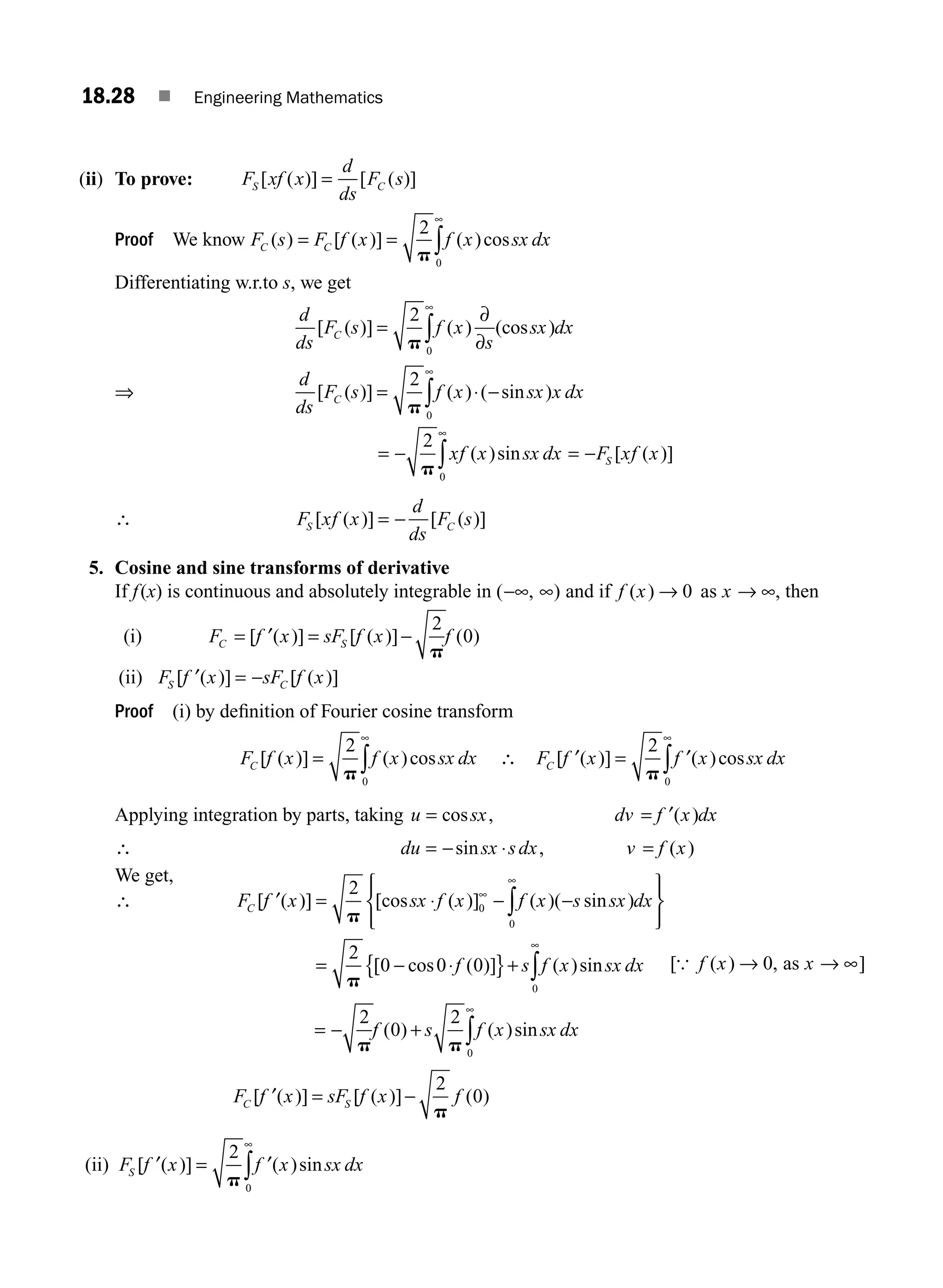

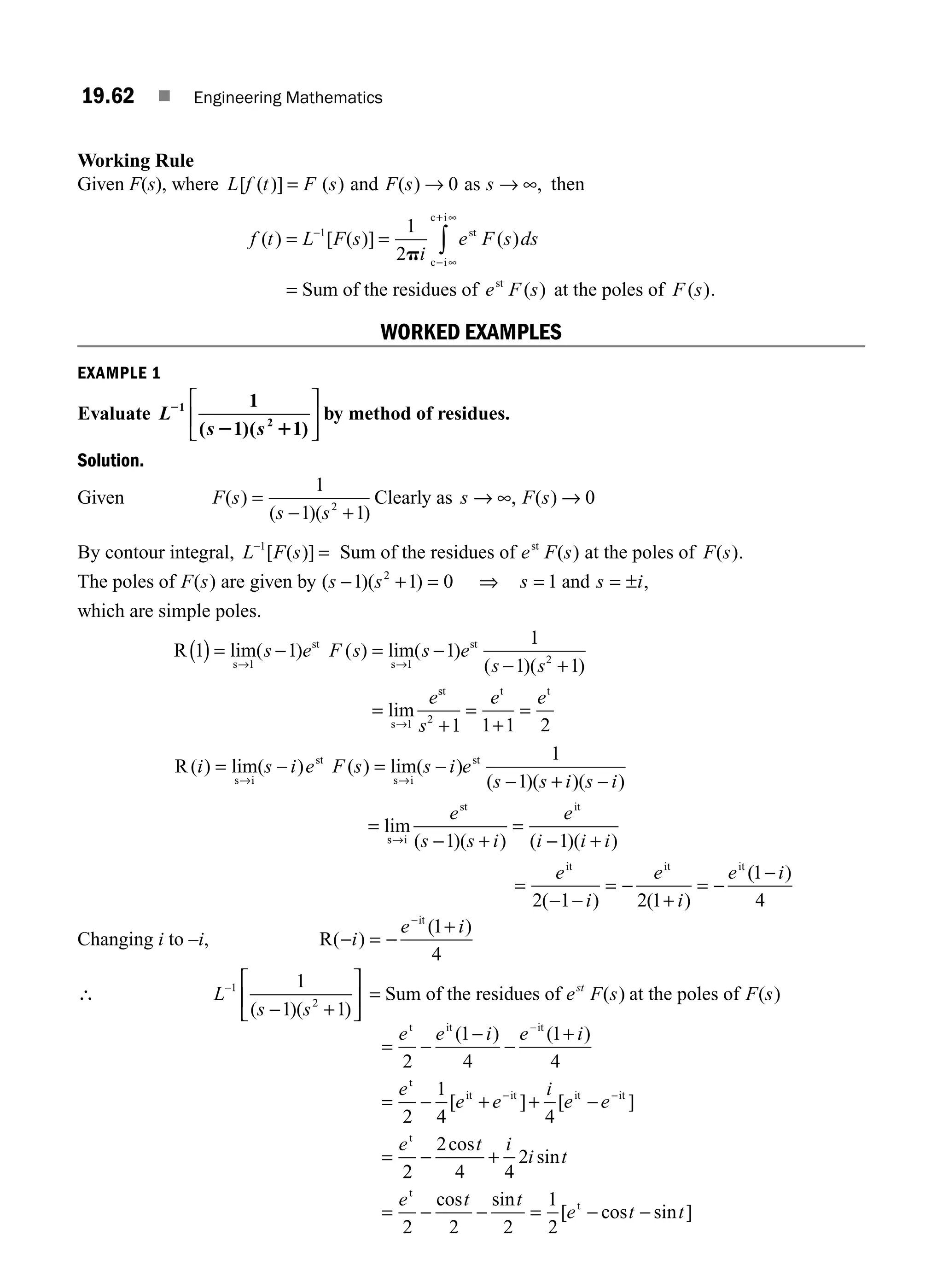

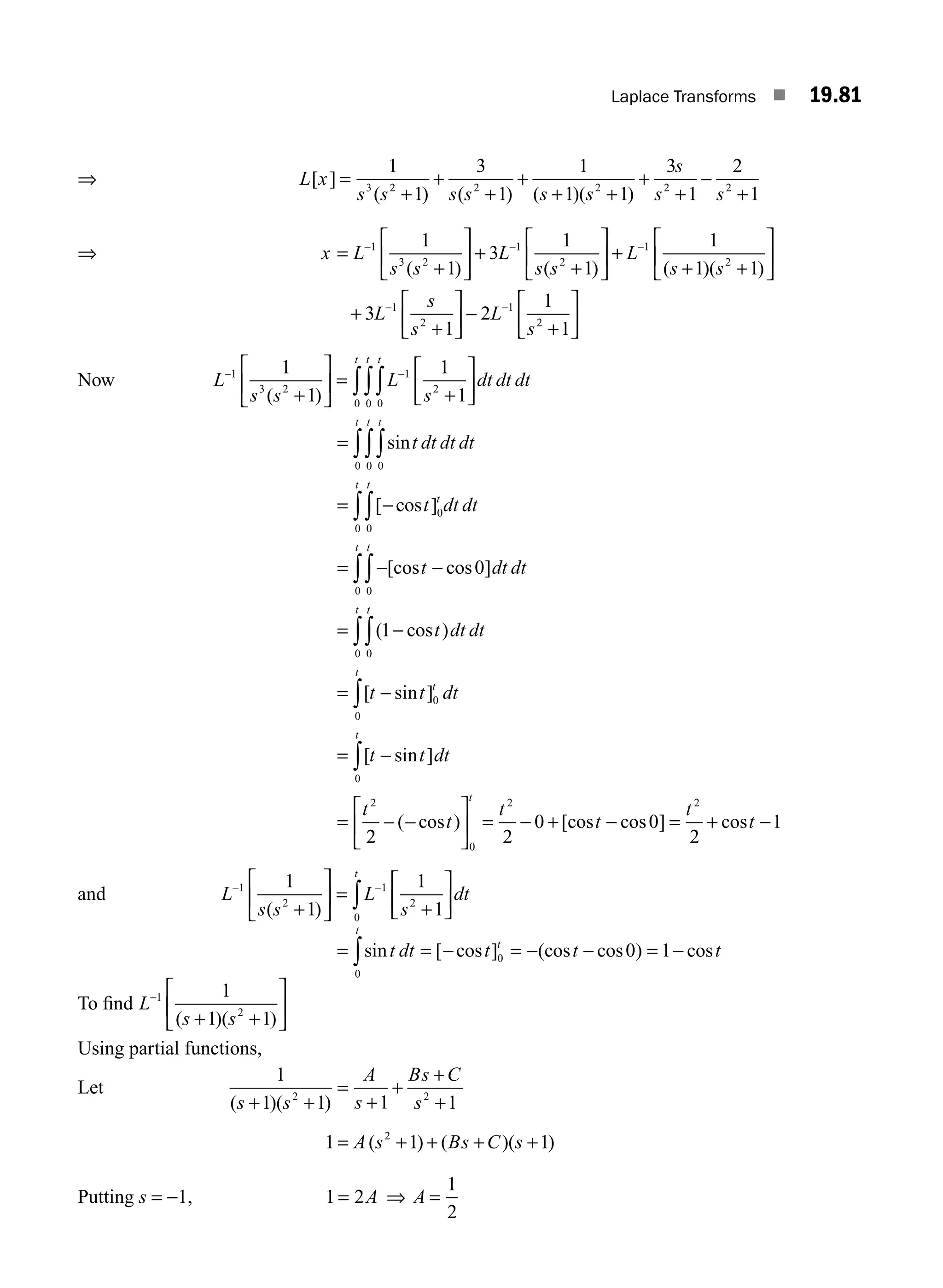

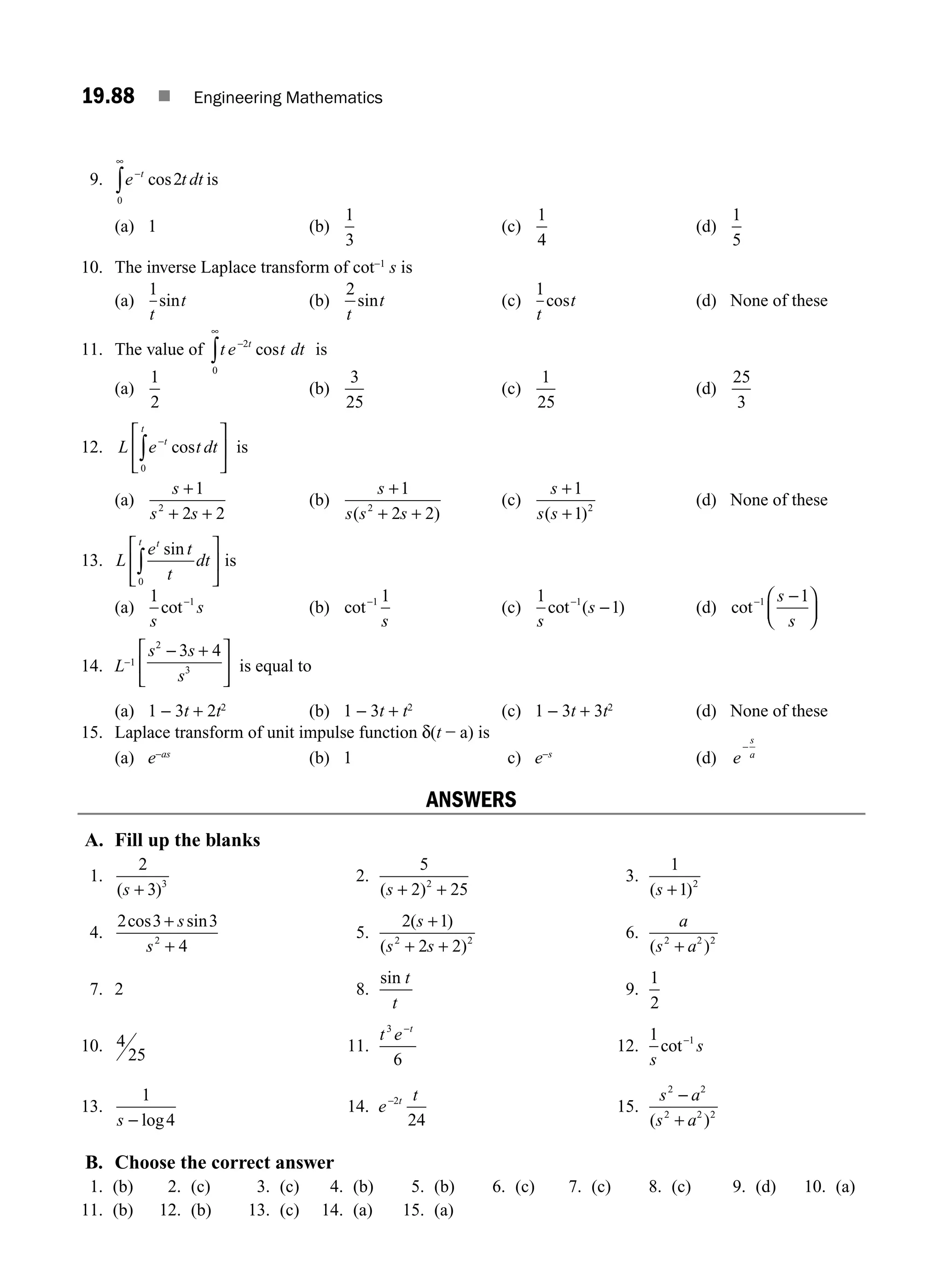

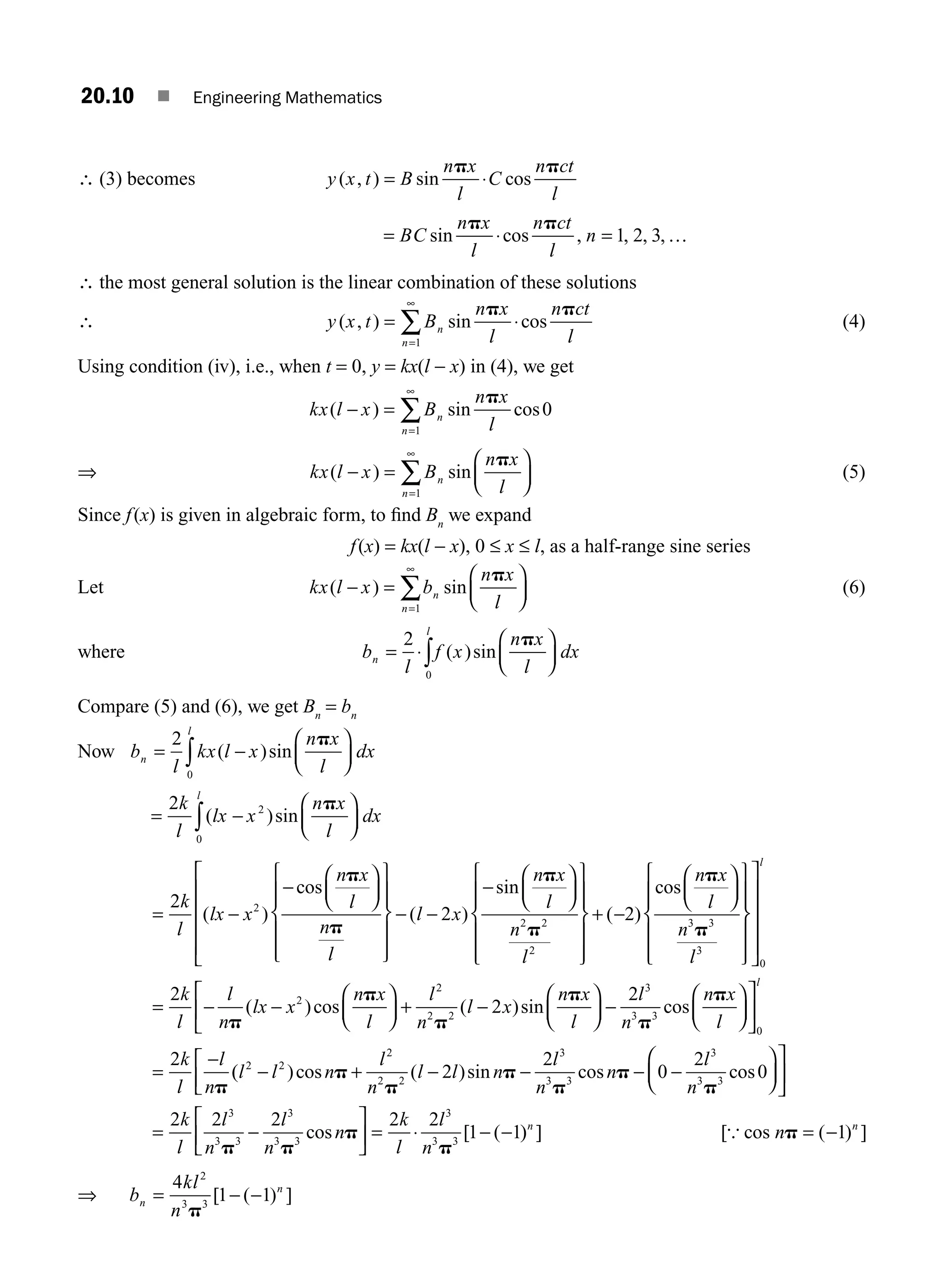

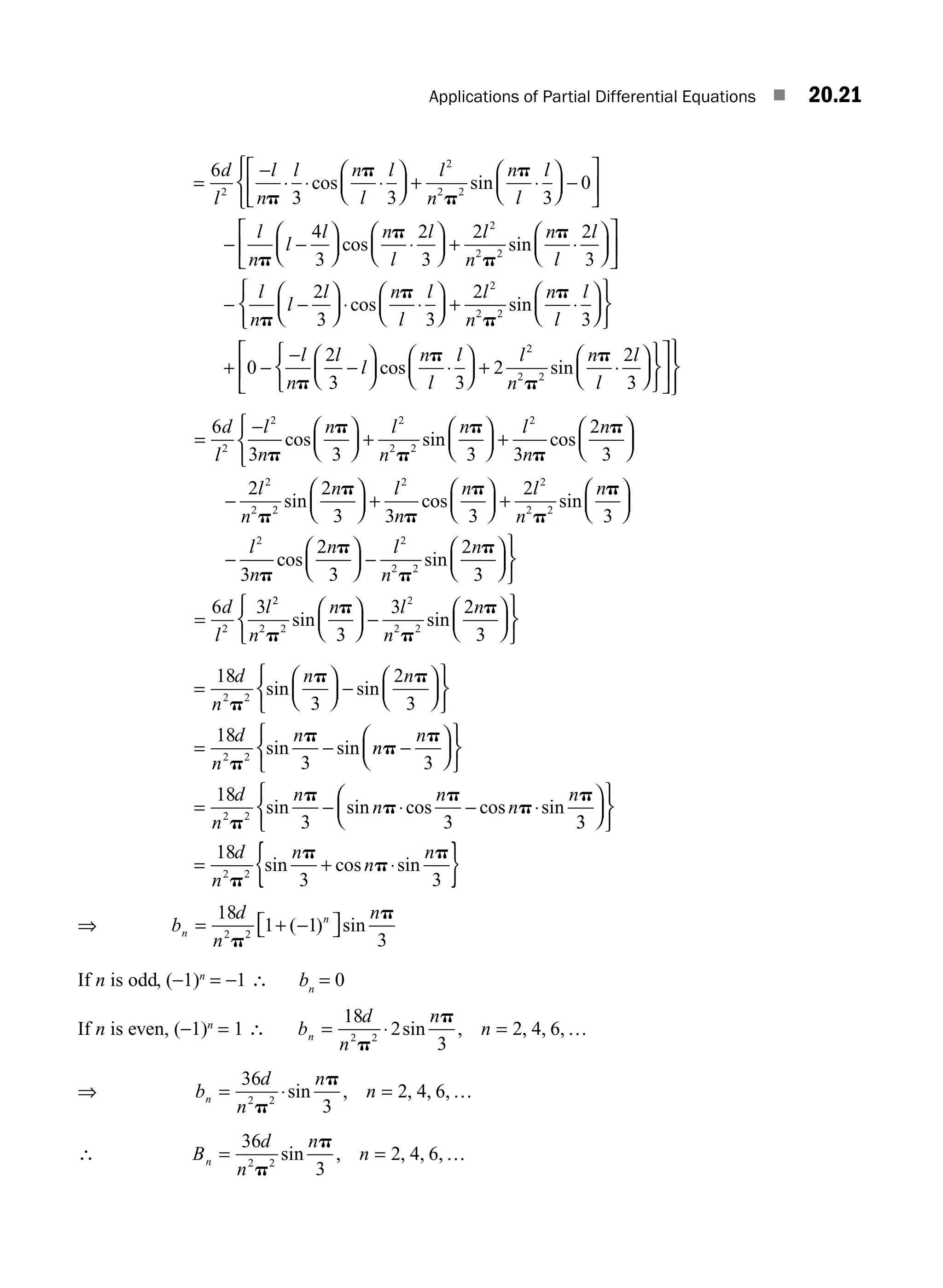

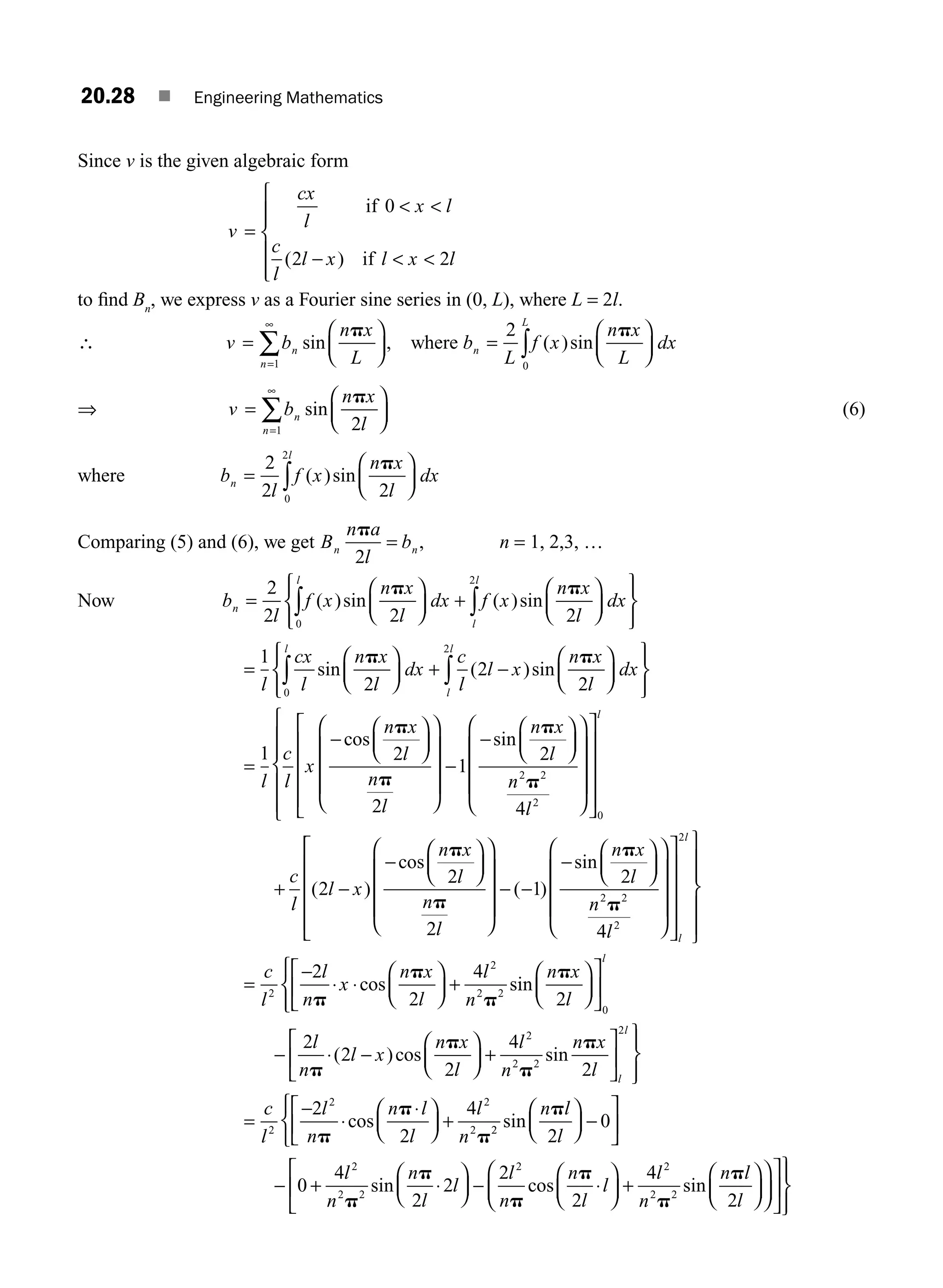

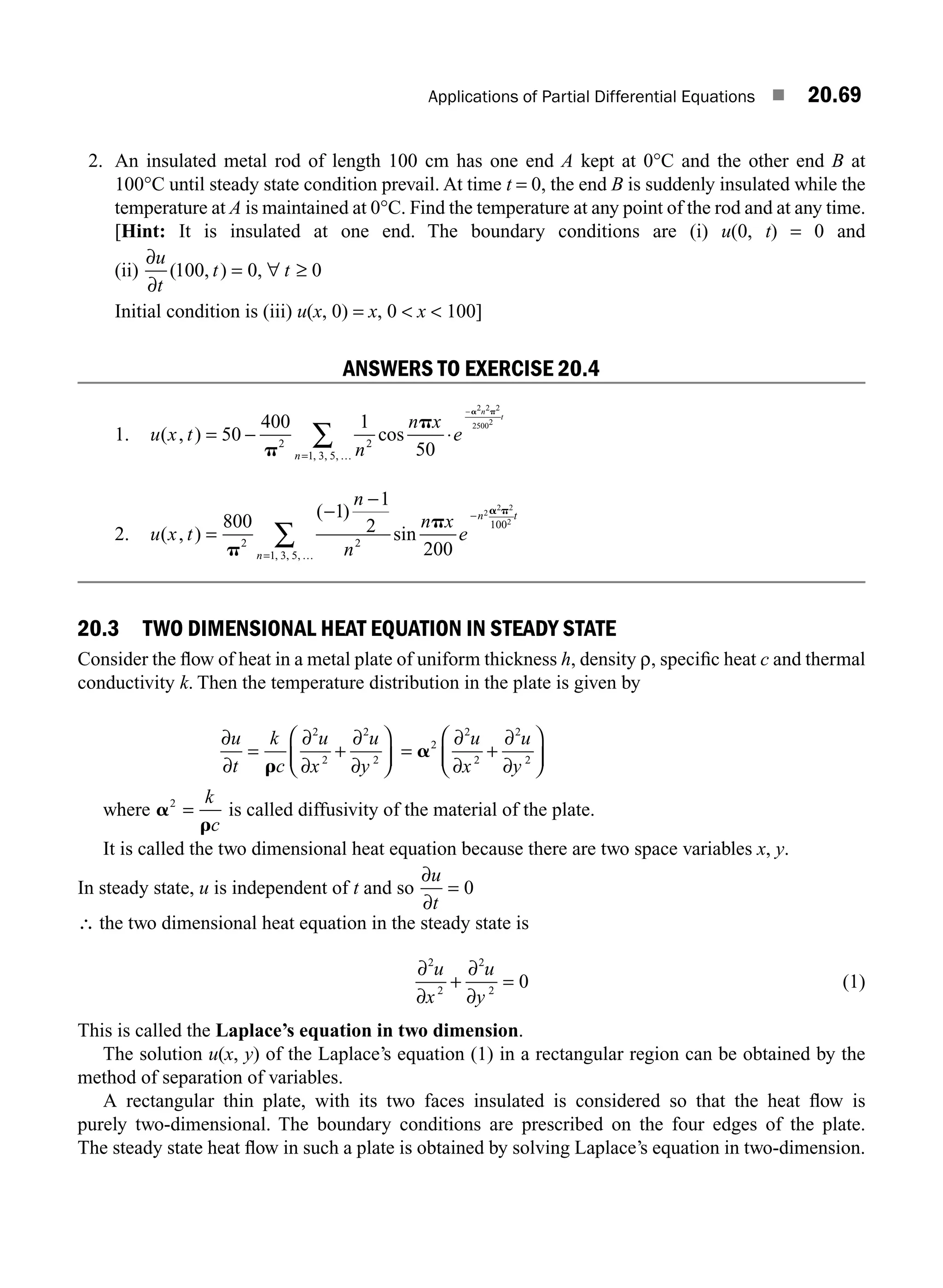

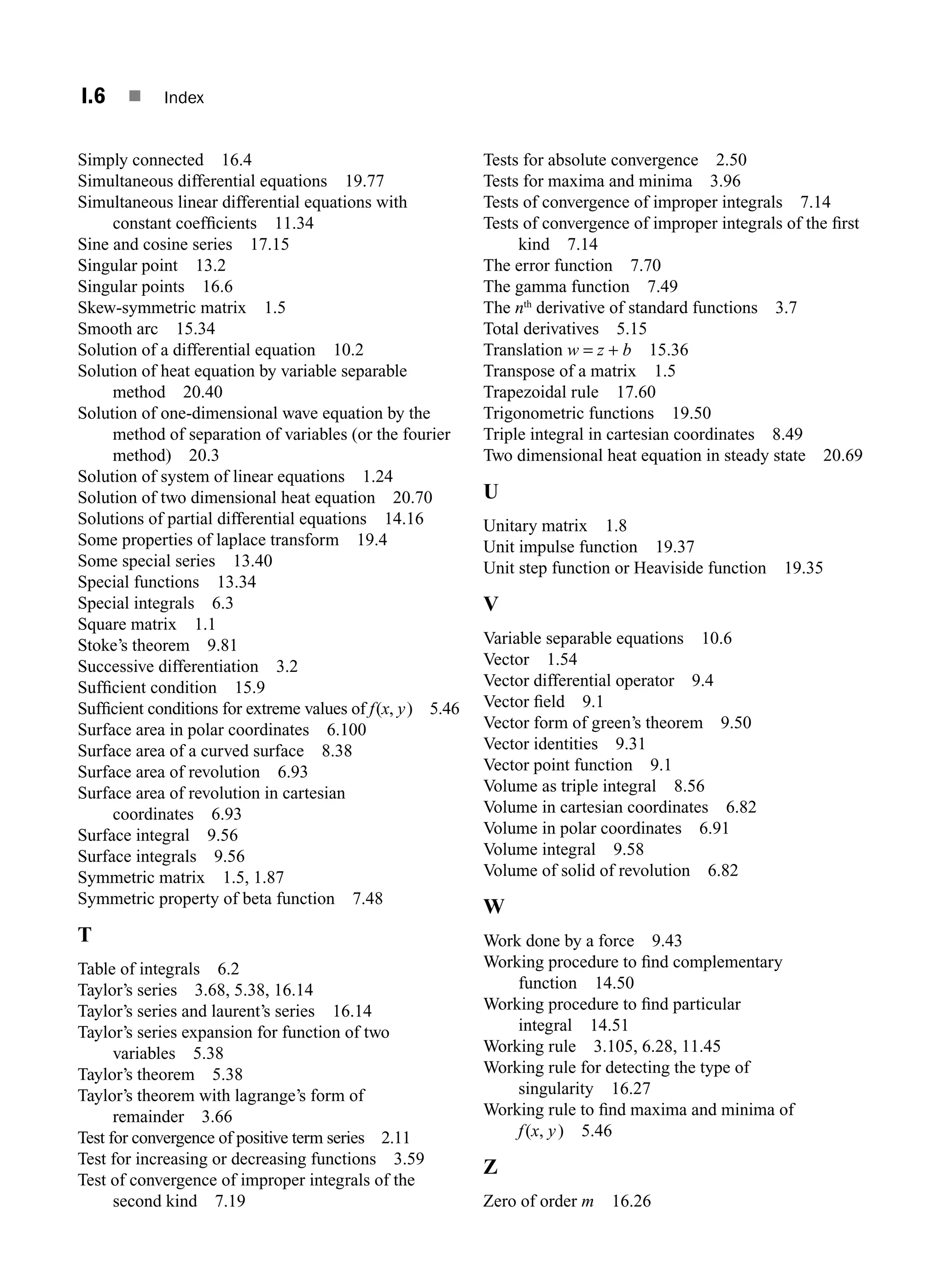

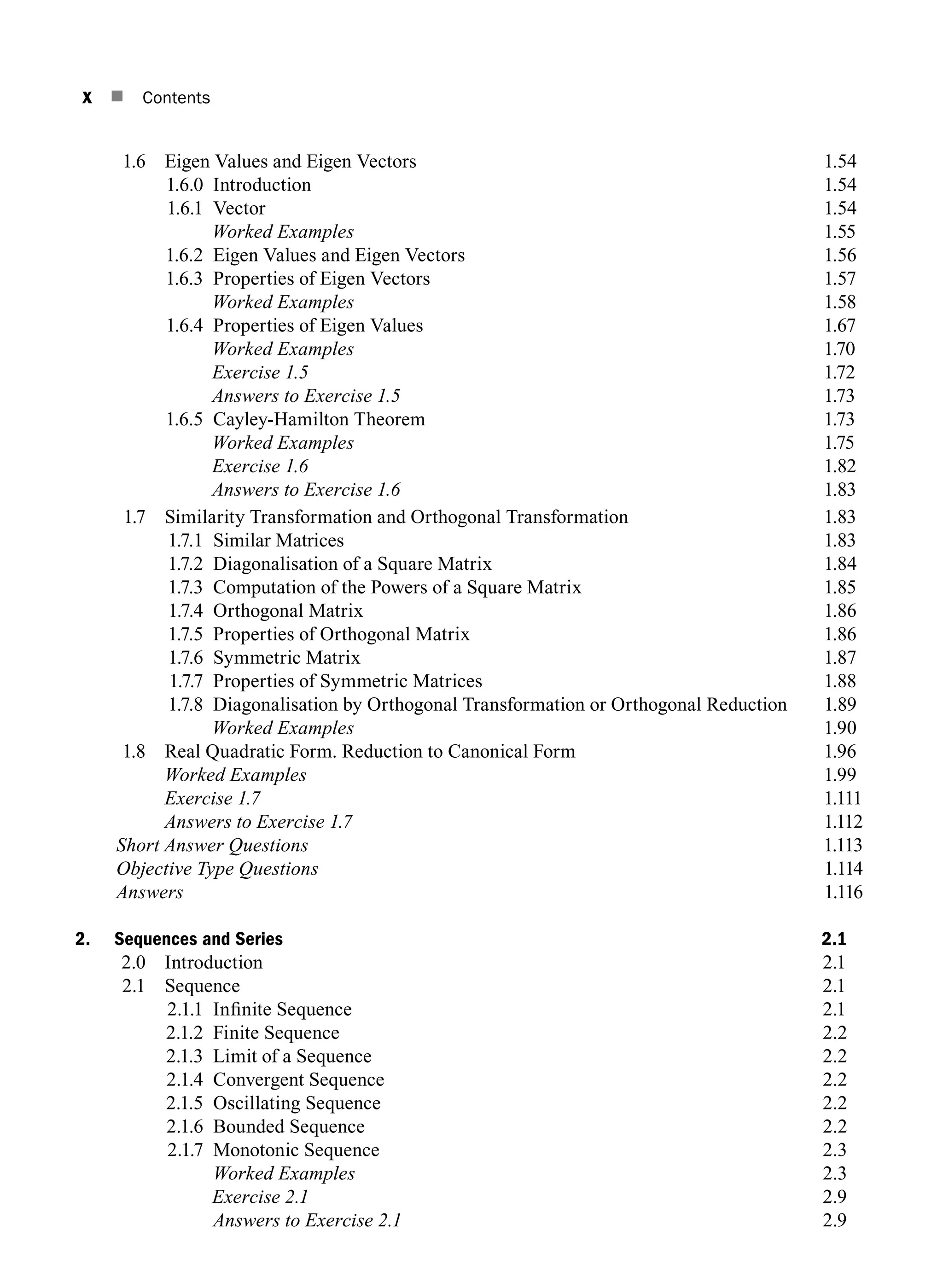

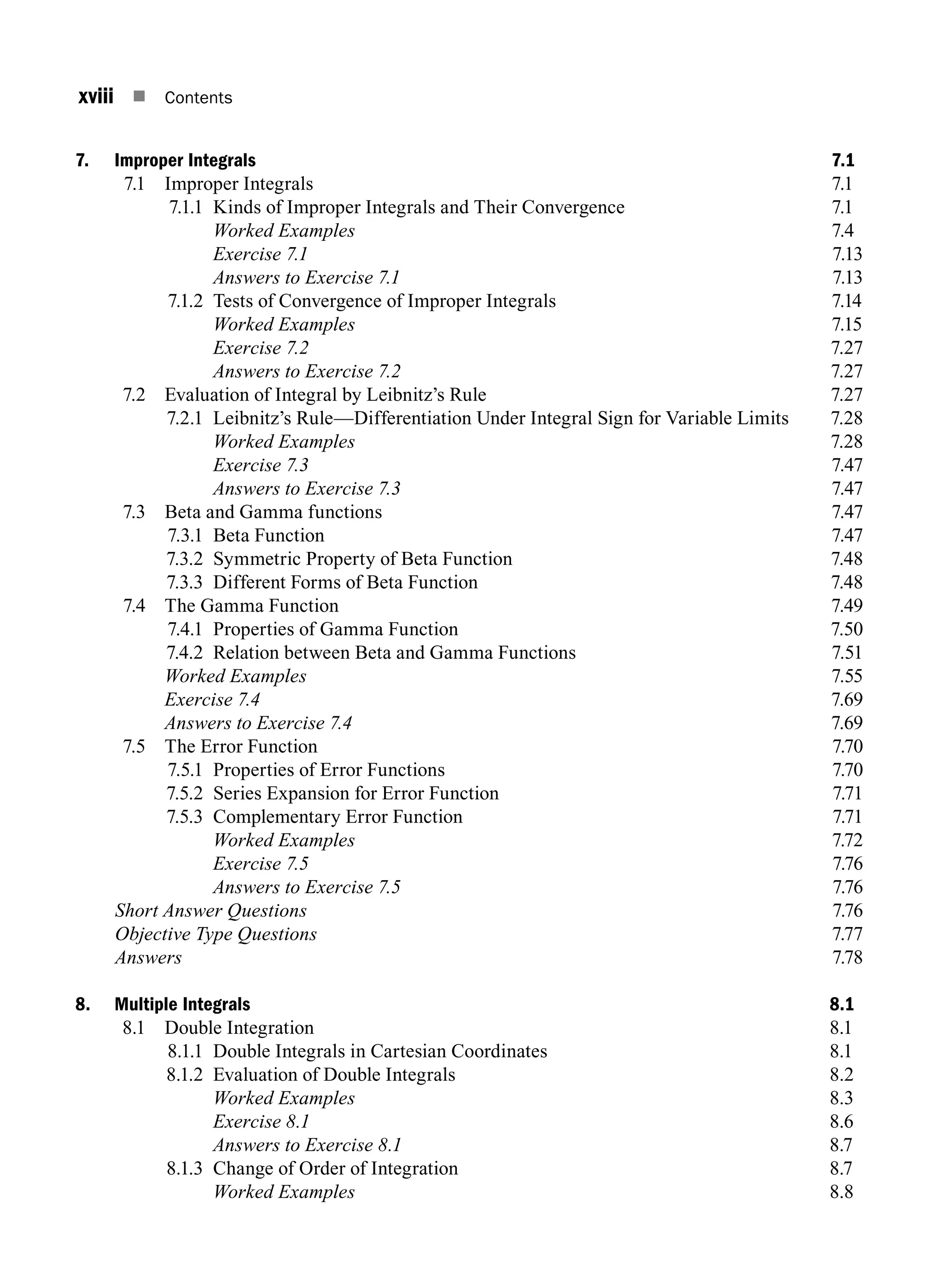

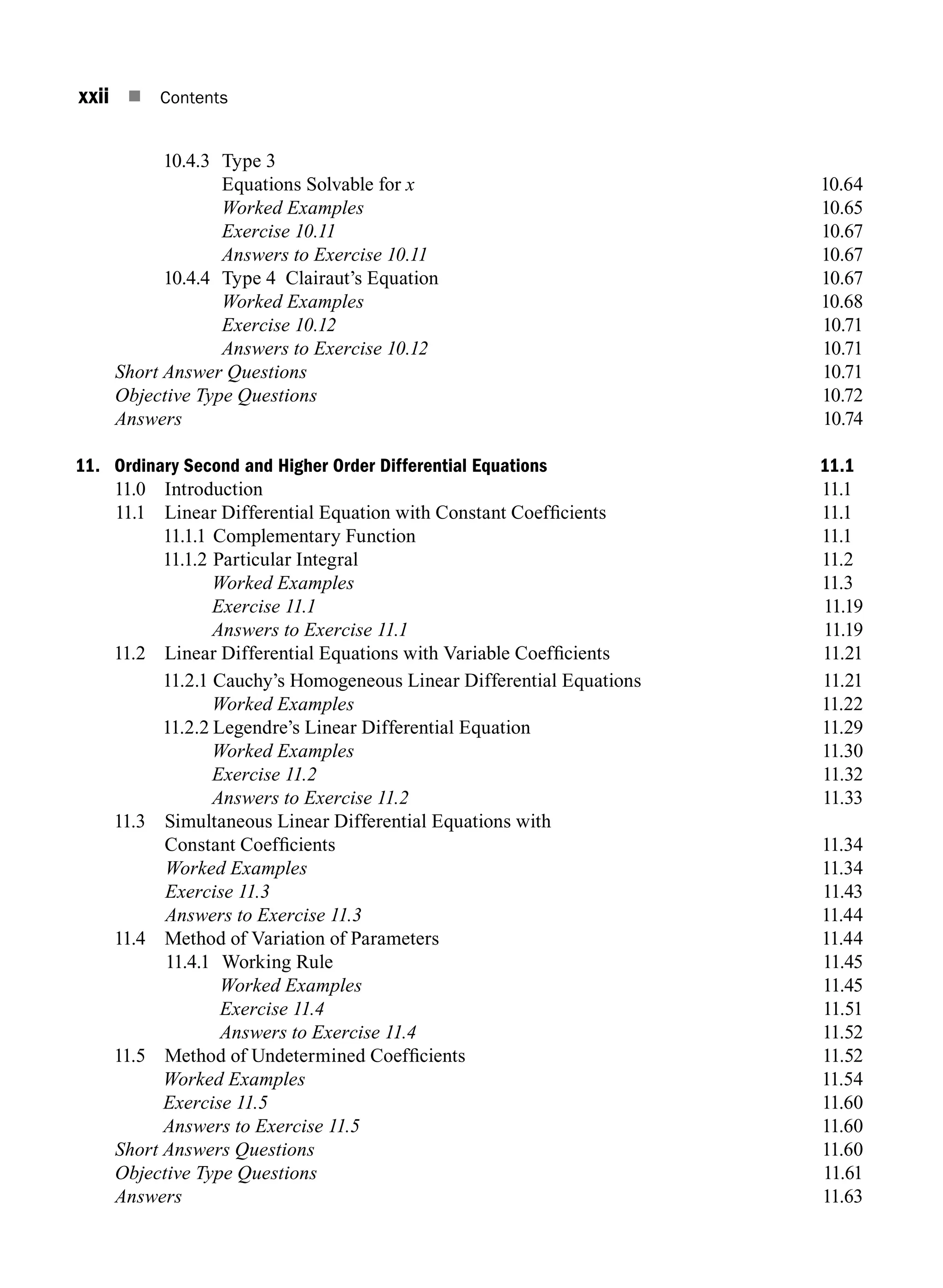

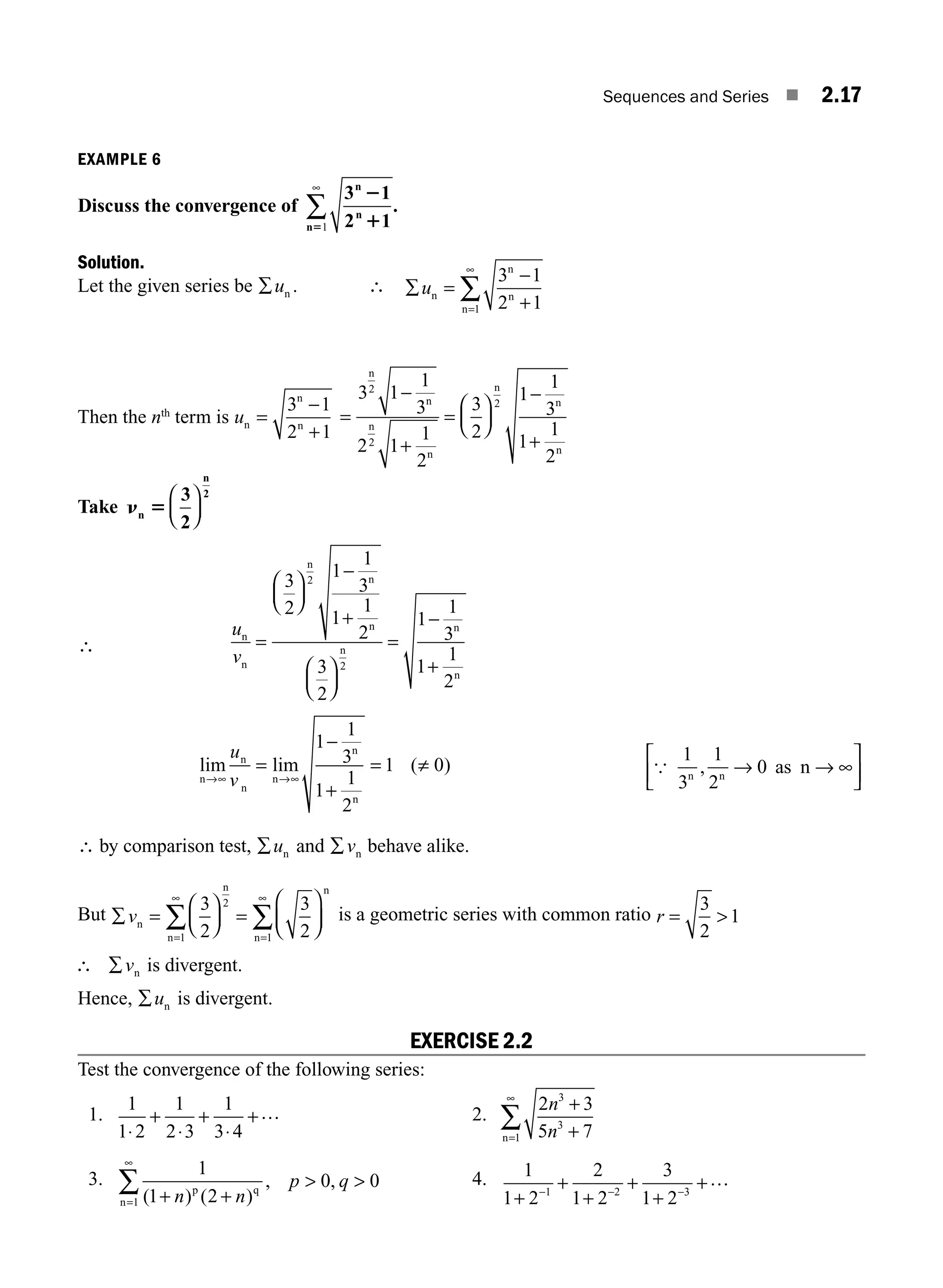

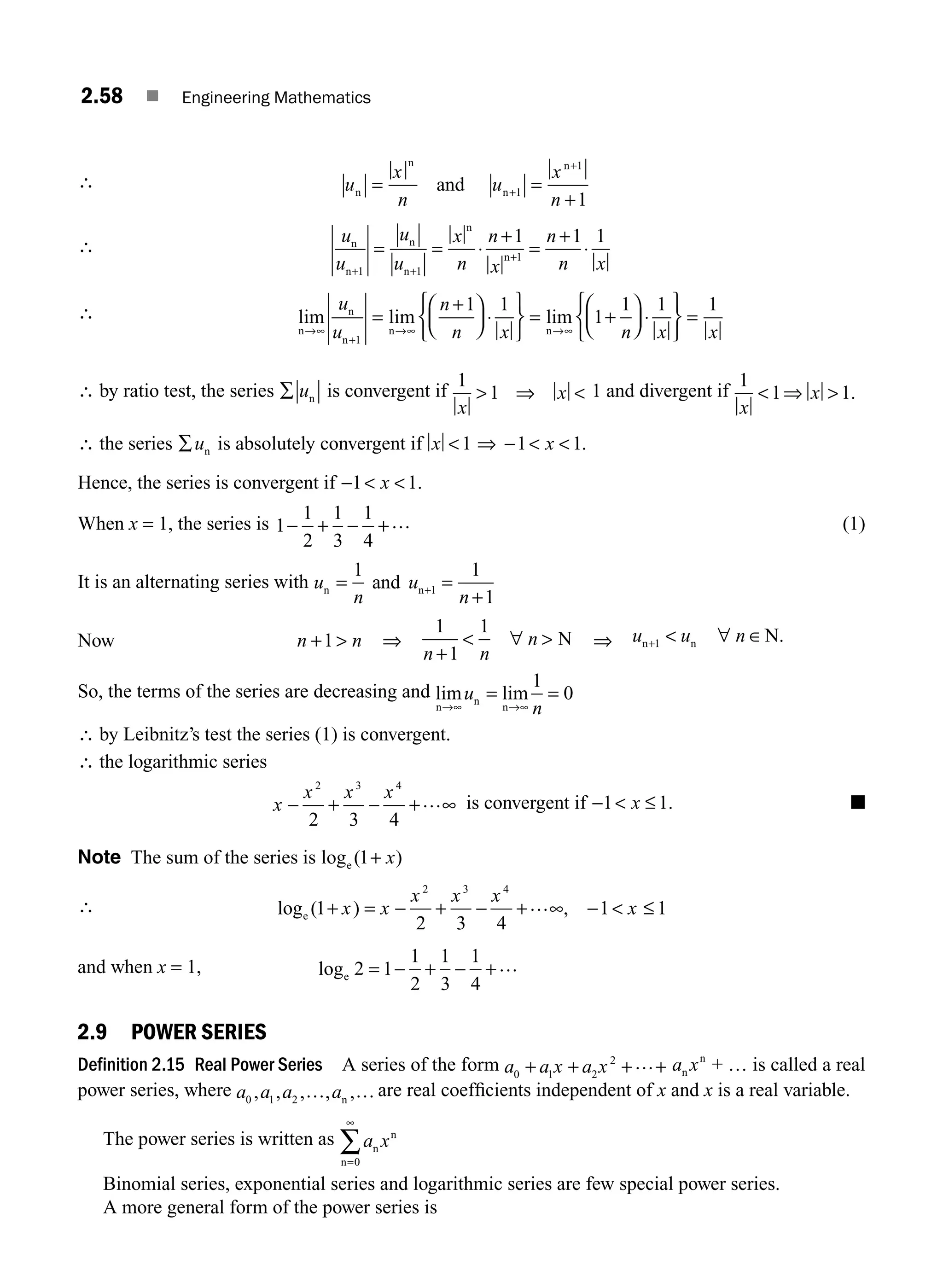

![Matrices ■ 1.3

Definition 1.6 Scalar Matrix

In a diagonal matrix if all the diagonal elements are equal to a non-zero scalar a, then it is called a

scalar matrix.

EXAMPLE 1.6

A =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

a

a

a

0 0

0 0

0 0

is a scalar matrix.

Definition 1.7 Unit Matrix or Identity Matrix

In a diagonal matrix, if all the diagonal elements are equal to 1, then it is called a Unit matrix or

identity matrix.

EXAMPLE 1.7

[ ], ,

1

1 0

0 1

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

are identity matrices of orders 1, 2, 3 respectively. They are denoted by I1

, I2

, I3

.

In general, In

is the identity matrix of order n.

Definition 1.8 Zero Matrix or Null Matrix

In a matrix (rectangular or square), if all the entries are equal to 0, then it is called a zero matrix or

null matrix.

EXAMPLE 1.8

A B

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

0 0

0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

, are zero matrices of types 2 × 2 and 2 × 4.

Definition 1.9 Triangular matrix

A square matrix A = [aij

] is said to be an upper triangular matrix if all the entries below the main

diagonal are zero.

That is aij

= 0 if i j

A square matrix A = [aij

] is said to be a lower triangular matrix if all the entries above the main

diagonal are zero.

That is aij

= 0 if i j

EXAMPLE 1.9

(1) The matrices A B

=

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 3

0 1 4

0 0 5

4 1 0 2

0 2 3 1

0 0 0 2

0 0 0 5

and are upper triangular matrices.

(2) The matrices A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 0

1 0

and B = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 0 0

2 1 0

0 2 1

are lower triangular matrices.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 3 5/30/2016 4:34:39 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-40-2048.jpg)

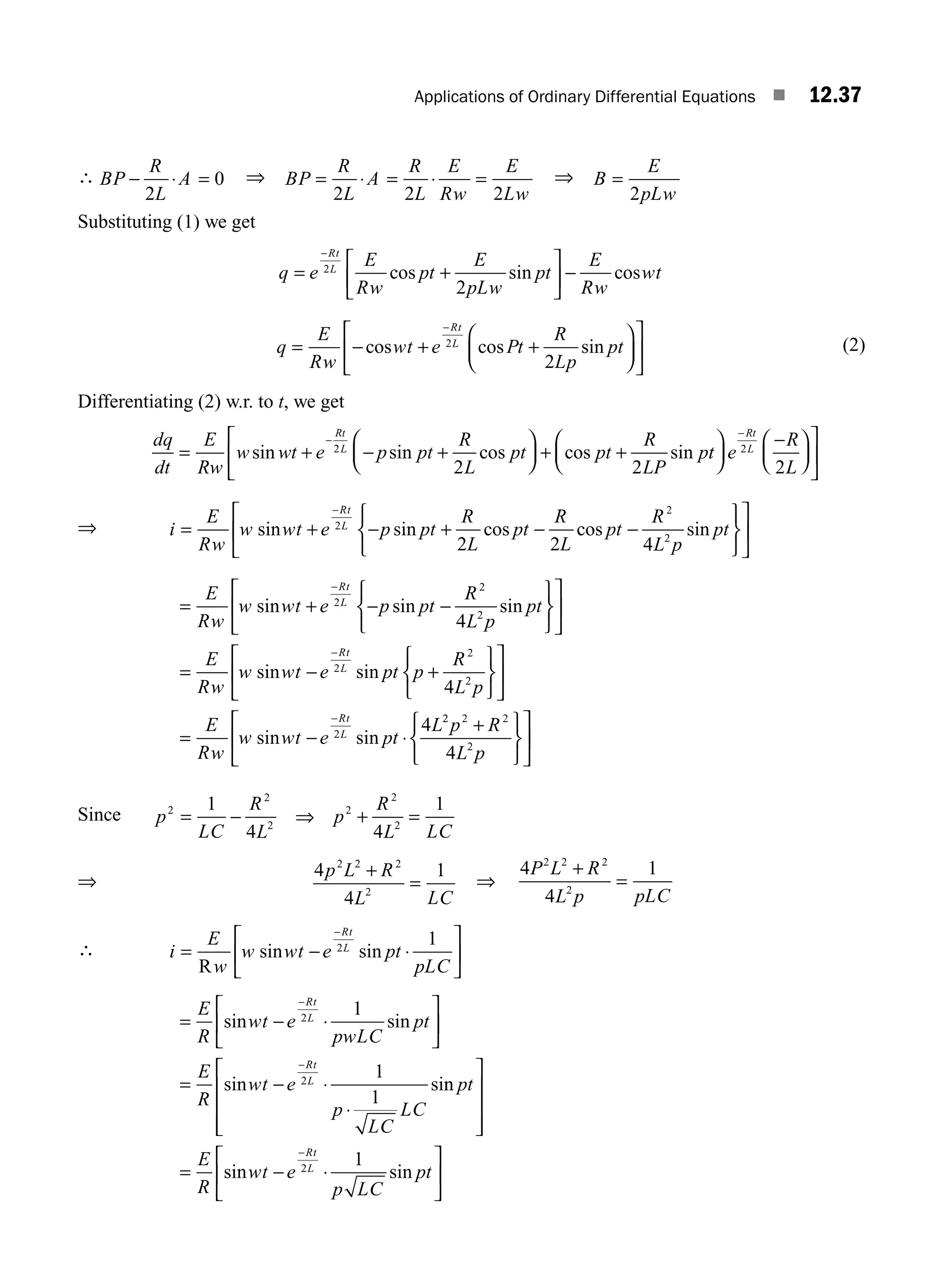

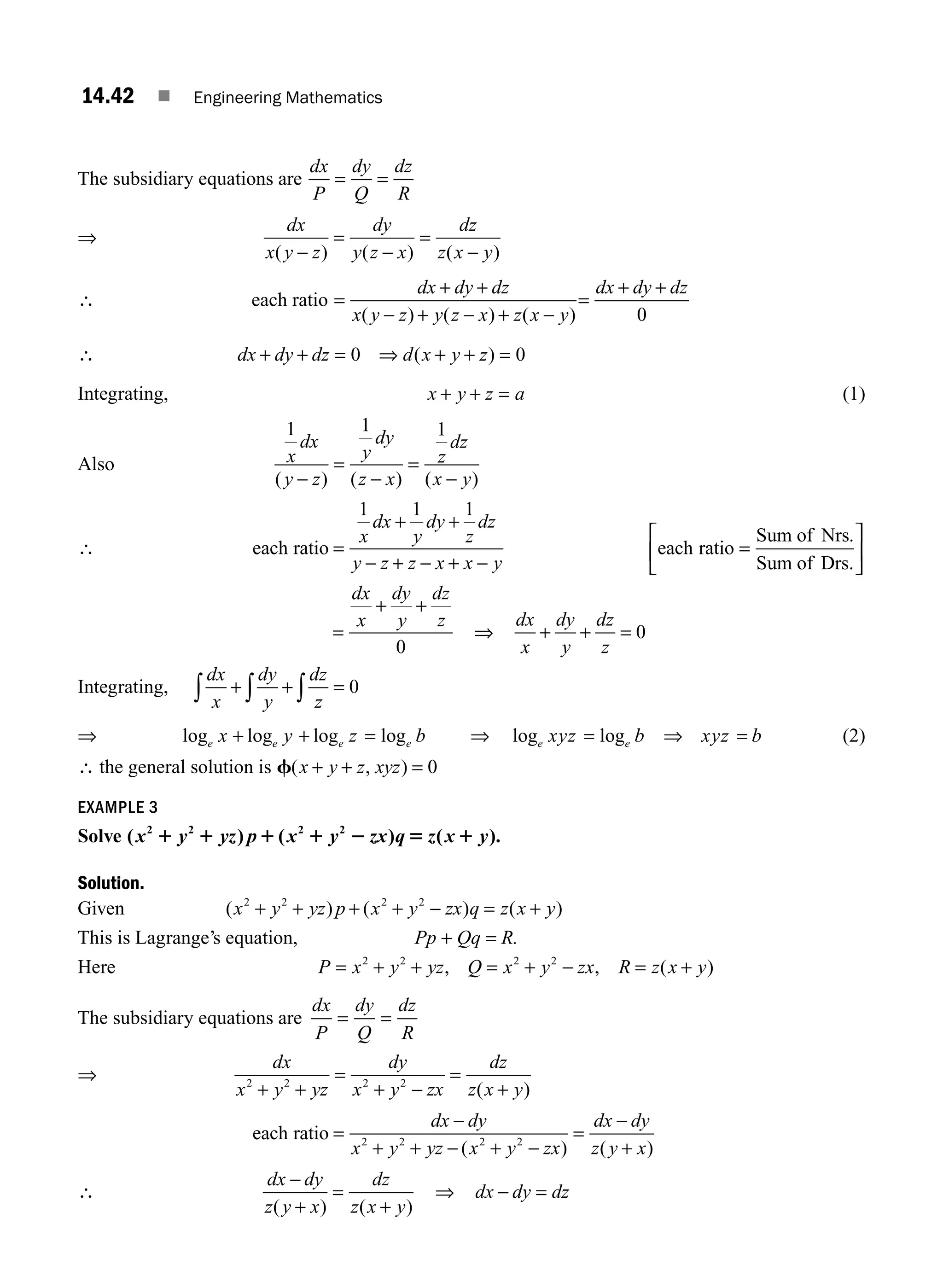

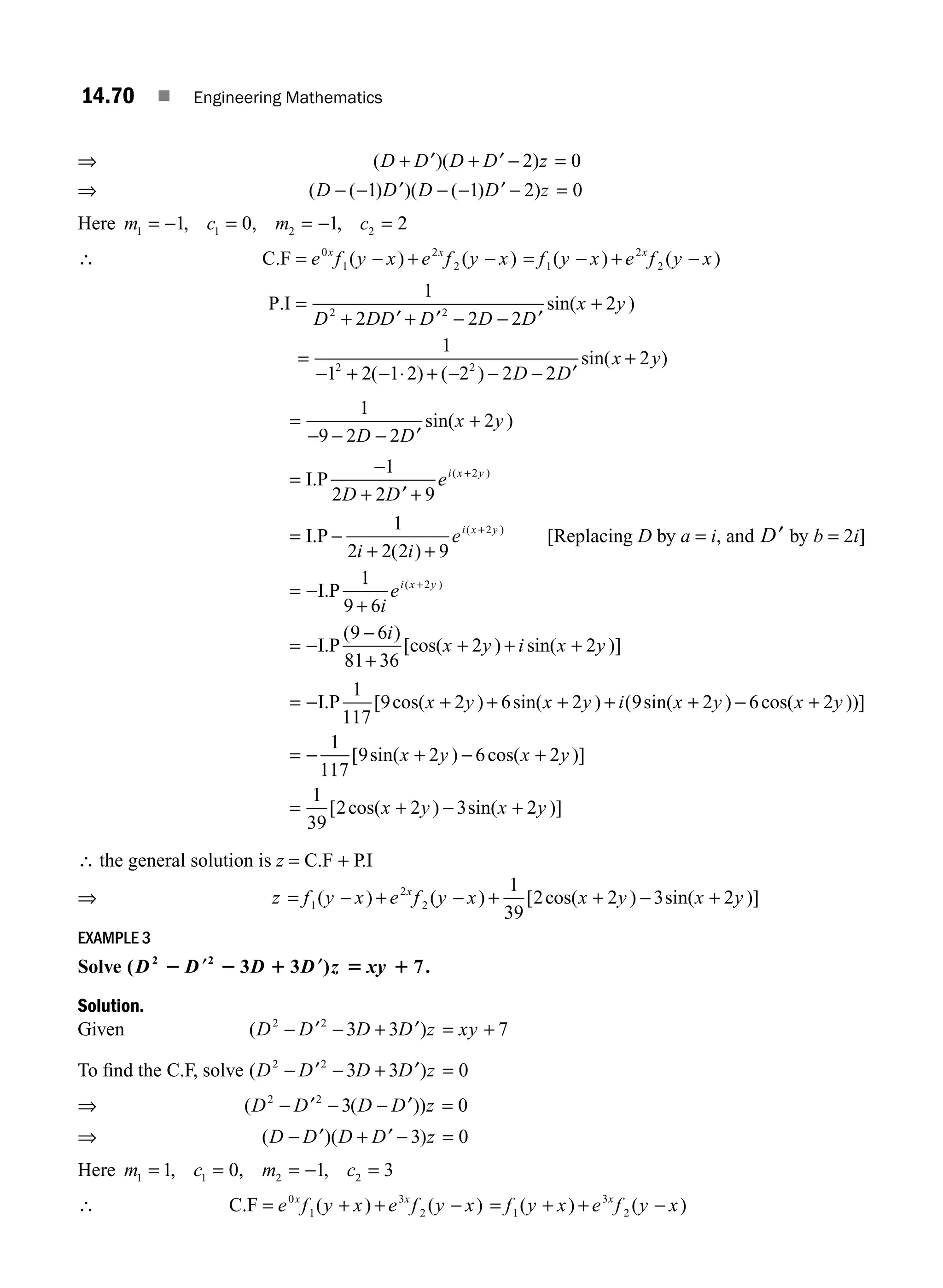

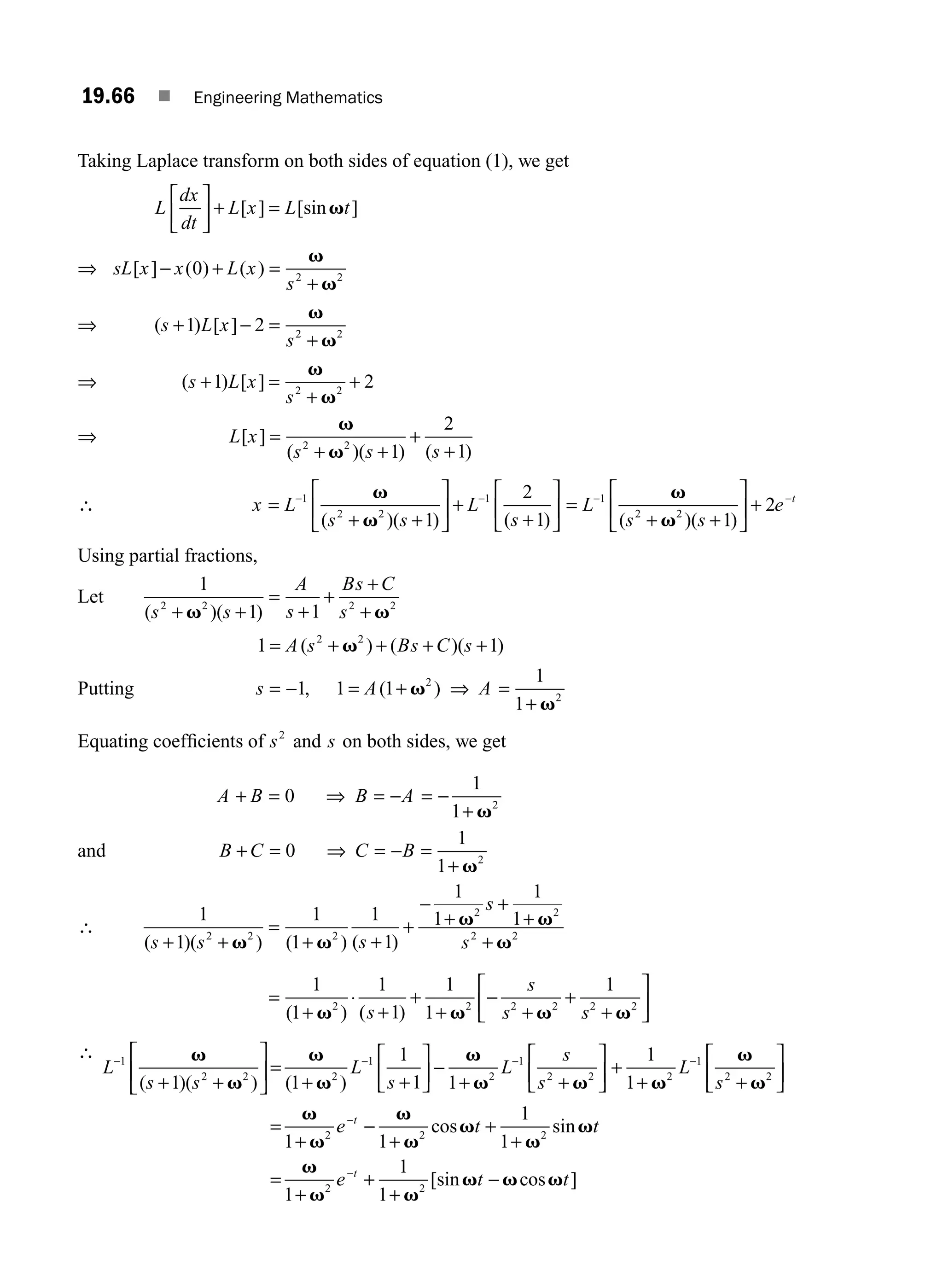

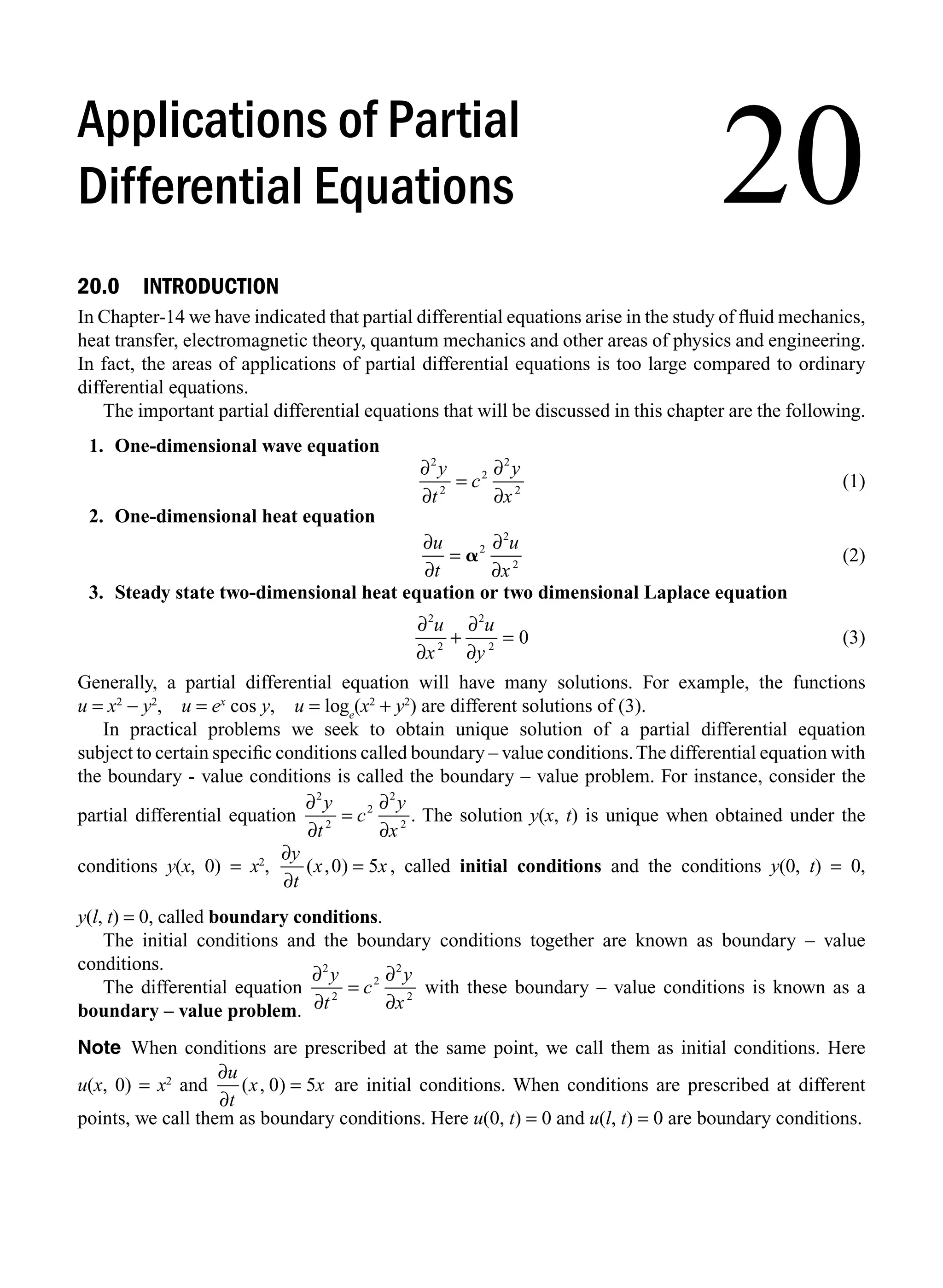

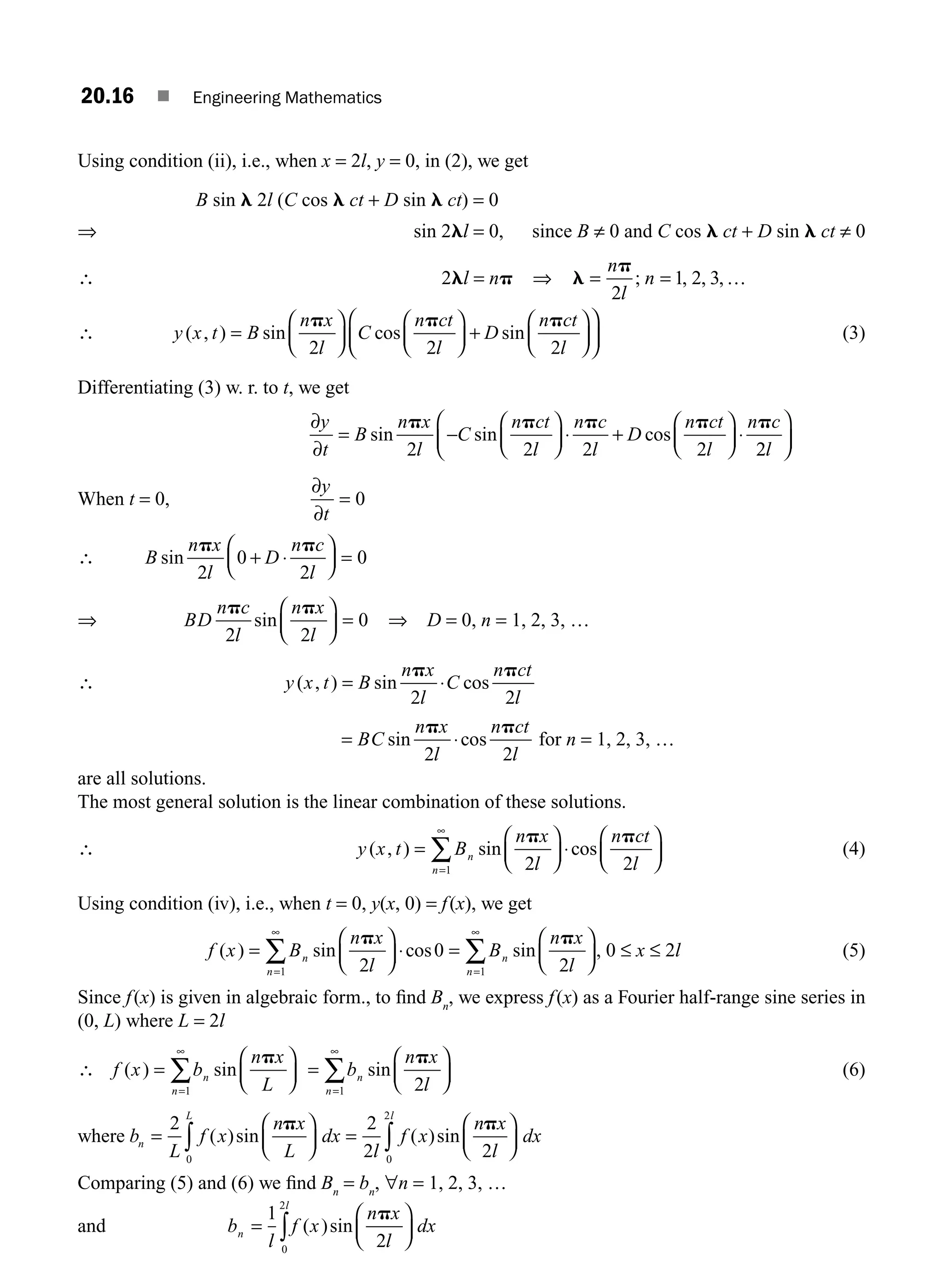

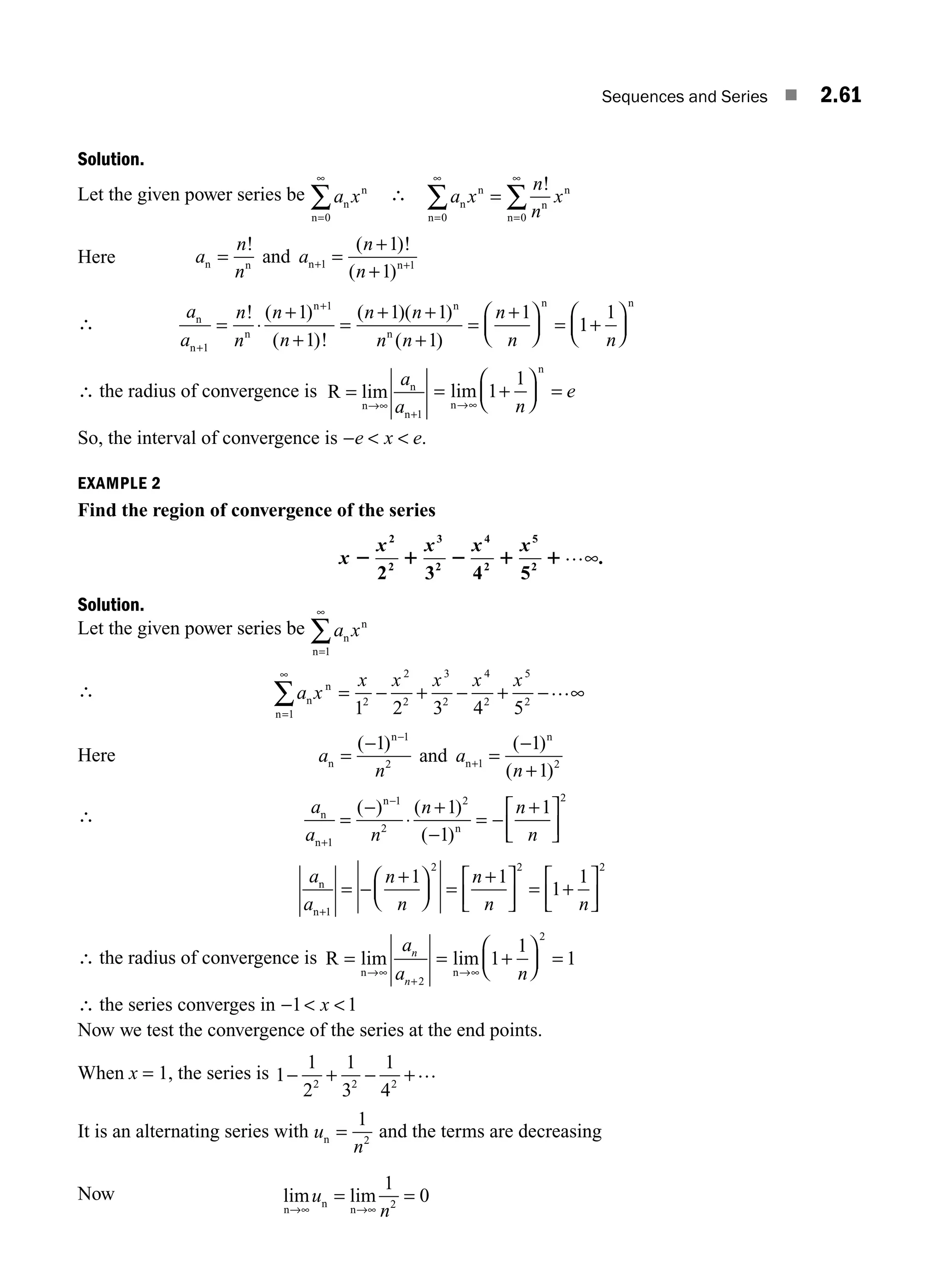

![1.4 ■ Engineering Mathematics

1.1.1 Basic Operations on Matrices

Definition 1.10 Equality of Matrices

Two matrices A = [aij

] and B = [bij

] of the same type m × n are said to be equal if aij

= bij

for all i, j and

is written as A = B.

Definition 1.11 Addition of Matrices

Let A = [aij

] and B = [bij

] of the same type m × n. Then A + B = [cij

], where cij

= aij

+ bij

for all i and j

and A + B is of type m × n.

EXAMPLE 1.10

If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

1 2 3

0 1 5

and B =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

1 2 3

1 0 2

, then A B

+ =

− + + +

+ + −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

1 1 2 2 3 3

0 1 1 0 5 2

0 4 6

1 1 3

We see that A and B are of type 2 × 3 and A + B is also of type 2 × 3.

Definition 1.12 Scalar Multiplication of a Matrix

Let A = [aij

] be an m × n matrix and k be a scalar, then kA = [kaij

].

EXAMPLE 1.11

If A

a a a

a a a

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

11 12 13

21 22 23

, then kA

ka ka ka

ka ka ka

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

11 12 13

21 22 23

.

In particular if k = −1, then − =

− − −

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

A

a a a

a a a

11 12 13

21 22 23

.

Multiplication of Matrices

If A and B are two matrices such that the number of columns of A is equal to the number of rows of

B, then the product AB is defined. Two such matrices are said to be conformable for multiplication.

In the product AB, A is known as pre-factor and B is known as post-factor.

Definition 1.13 Let A = [aij

] be an m × p matrix and B = [bij

] be an p × n matrix, then AB is defined and

AB = [cij

] is an m × n matrix, where c a b

ij ik kj

k

p

=

=

∑1

.

That is cij

is the sum of the products of the corresponding elements of the ith

row of A and the jth

column of B.

EXAMPLE 1.12

Let A B

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 2

0 1 3

2 2 1

1 2

3 1

2 1

and

Since A is of type 3 × 3 and B is of type 3 × 2, AB is defined and AB is of type 3 × 2.

AB =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅ ⋅ + ⋅ +

1 1 2

0 1 3

2 2 1

1 2

3 1

2 1

1 1 1 3 2 2 1 2 1 1 2

2 1

0 1 1 3 3 2 0 2 1 1 3 1

2 1 2 3 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 1

⋅

⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅ ⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅

⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅ ⋅ + ⋅ + ⋅

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

8 5

9 4

10 7

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 4 5/30/2016 4:34:41 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-41-2048.jpg)

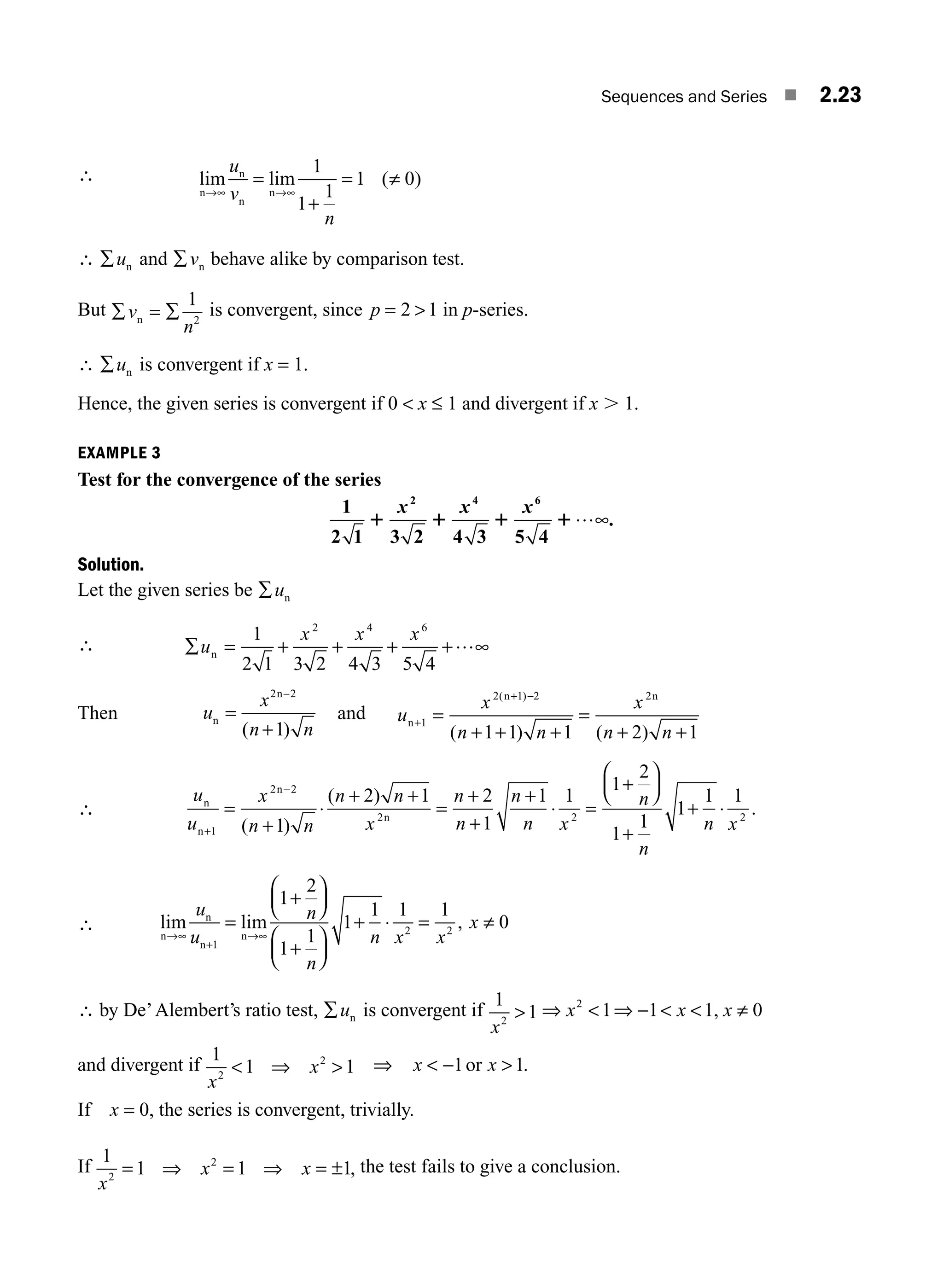

![Matrices ■ 1.5

Note If A and B are square matrices of order n, then both AB and BA are defined, but not necessarily

equal. That is, AB ≠ BA, in general.

So, matrix multiplication is not commutative.

1.1.2 Properties of addition, scalar multiplication and multiplication

1. If A, B, C are matrices of the same type, then

(i) A + B = B + A (ii) A + (B + C) = (A + B) + C

(iii) A + 0 = A (iv) A + (−A) = 0

(v) a(A + B) = aA + aB (vi) (a + b)A = aA + bA

(vii) a(bA) = (ab)A for any scalars a, b.

2. If A, B, C are conformable for multiplication, then

(i) a(AB) = (aA)B = A(aB)

(ii) A(BC) = (AB)C

(iii) (A + B)C = AC + BC, where A and B are of type m × p and C is of type p × n.

(iv) If A is a square matrix, then

A2

= A × A, A3

= A2

× A, …, An

= An − 1

× A

Definition 1.14 Transpose of a Matrix

Let A = [aij

] be an m × n matrix. The transpose of A is obtained by interchanging the rows and

columns of A and it is denoted by AT

.

∴ =

A a

T

ji

[ ] is a n × m matrix.

Properties:

(i) (AT

)T

= A (ii) (A + B)T

= AT

+ BT

(iii) (AB)T

= BT

AT

(iv) (aA)T

= aAT

Definition 1.15 Symmetric Matrix

A square matrix A = [aij

] of order n is said to be symmetric if AT

= A.

This means [aji

] = [aij

] ⇒ aji

= aij

for i, j = 1, 2, …n

Thus, in a symmetric matrix elements equidistant from the main diagonal are the same.

EXAMPLE 1.13

A

a h g

h b f

g f c

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

and B =

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 3 4

2 0 5 7

3 5 2 8

4 7 8 4

are symmetric matrices of orders 3 and 4.

Definition 1.16 Skew-Symmetric Matrix

A square matrix A = [aij

] of order n is said to be skew-symmetric if AT

= −A.

This means [aji

] = −[aij

] ⇒ aji

= − aij

for all i, j = 1, 2, …, n

In particular, put j = i, then aii

= − aii

⇒ 2aii

= 0 ⇒ aii

= 0 for all i = 1, 2, …, n

So, in a skew-symmetric matrix, the diagonal elements are all zero and elements equidistant from

the main diagonal are equal in magnitude, but opposite in sign.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 5 5/30/2016 4:34:41 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-42-2048.jpg)

![1.6 ■ Engineering Mathematics

EXAMPLE 1.14

A B

=

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

0 1

1 0

0 2 3

2 0 4

3 4 0

and are skew-symmetric matrices of orders 2 and 3.

Definition 1.17 Non-Singular Matrix

A Square matrix A is said to be non-singular if A ≠ 0 ( A means determinant of A).

If A = 0, then A is singular.

Definition 1.18 Minor and Cofactor of an Element

Let A = [aij

] be a square matrix of order n. If we delete the row and column of the element aij

, we get

a square submatrix of order (n − 1).

The determinant of this submatrix is called the minor of the element aij

and is denoted by Mij

.

The cofactor of aij

in A is A M

ij

i j

ij

= − +

( )

1

EXAMPLE 1.15

A = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 6 2

0 2 4

3 1 2

The cofactor of a11

= 1 is A11

1 1

1

2 4

1 2

= −

−

+

( ) = −4 −4 = −8

The cofactor of a12

= 6 is A12

1 2

1

0 4

3 2

= − +

( ) = − (−12) = 12

The cofactor of a32

= 1 is A32

3 2

1

1 2

0 4

= − +

( ) = − (4 −0) = −4

Similarly, we can determine the cofactors of other elements.

Definition 1.19 Adjoint of a Matrix

Let A = [aij

] be a square matrix. The adjoint of A is defined as the transpose of the matrix of cofactors

of the elements of A and it is denoted by adj A.

Thus, adj A

A A A

A A A

A A A

n

n

n n nn

T

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

11 12 1

21 21 2

1 2

…

…

…

: : :

Properties: If A and B are square matrices of order n, then

(i) adj AT

= (adj A)T

(ii) (adj A) A = A (adj A) = A In

.

(iii) adj(AB) = (adj A) (adj B)

Using property (ii), we define inverse.

Definition 1.20 Inverse of a Matrix

If A is a non-singular matrix, then the inverse of A is defined as

adj A

A

and it is denoted by A−1

.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 6 5/30/2016 4:34:44 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-43-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.7

∴ A

A

A

−

=

1 adj

EXAMPLE 1.16

Find the inverse of A = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 6 2

0 2 4

3 1 2

.

Solution.

Given A = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 6 2

0 2 4

3 1 2

∴ A = −

1 6 2

0 2 4

3 1 2

= 1(−4 −4) −6(0 − 12) + 2(0 + 6) = −8 + 72 + 12 = 76 ≠ 0

Since A ≠ 0, A is non-singular and hence A−1

exists and A

A

A

−

=

1 adj

.

We shall find the cofactors of the elements of A

A A

A

11

1 1

12

1 2

13

1

2 4

1 2

4 4 8 1

0 4

3 2

0 12 12

= −

−

= − − = − = − = − − =

=

+ +

( ) ( ) , ( ) ( )

(−

−

−

= + = = − = − − = −

= −

+ +

+

1

0 2

3 1

0 6 6 1

6 2

1 2

12 2 10

1

1 3

21

2 1

22

2

) ( ) , ( ) ( )

( )

A

A 2

2

23

2 3

31

3 1

1 2

3 2

2 6 4 1

1 6

3 1

1 18 17

1

6 2

2 4

= − = − = − = − − =

= −

−

+

+

( ) , ( ) ( )

( )

A

A =

= + = = − = − − = −

= −

−

= − −

+

+

( ) , ( ) ( )

( ) (

24 4 28 1

1 2

0 4

4 0 4

1

1 6

0 2

2

32

3 2

33

3 3

A

A 0

0 2

) = −

∴

8 12 6

10 4 17

28 4 2

8 10 28

12 4 4

6 17

=

−

− −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

− −

− −

−

adj A

T

2

2

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

∴ A −

=

− −

− −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1

76

8 10 28

12 4 4

6 17 2

1.2 COMPLEX MATRICES

A matrix with at least one element as complex number is called a complex matrix.

Let A = [aij

] be a complex matrix.

The conjugate matrix of A is denoted by A and A aij

= ⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 7 5/30/2016 4:34:46 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-44-2048.jpg)

![1.8 ■ Engineering Mathematics

EXAMPLE 1.17

A

i i

i

=

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 2

3 2 0 3

is a complex matrix.

The conjugate of A is A

i i

i

i i

i

=

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

=

−

+

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 2

3 2 0 3

2 2

3 2 0 3

[{ conjugate of a + ib = a − ib]

We denote A

T

( ) by A*.

∴ A* is the transpose of the conjugate of A.

In the above example

A

i i

i

*

=

− +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 3 2

0

2 3

Note We have A A A A

T T T

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦ = ⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦ ∴ = ⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

∗

∴ If A a A a A a

ji

T

ji

T

ji

= = ⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

[ ], [ ],

then =[ ] ∴ A ∗

= [ ]

aji

Definition 1.21 Hermitian Matrix

A complex square matrix A is said to be a Hermitian matrix if A* = A and Skew-Hermitian matrix if

A* = −A.

A Hermitian matix is also denoted by AH

.

If A = [aij

], then A aji

* [ ]

= ∴ A* = A ⇒ aji = aij

for all i and j

Put j = i, then aii = aii

⇒ aii

are real numbers.

So, the diagonal elements of a Hermitian matrix are real numbers.

The elements equidistant from the main diagonal are conjugates.

A* = −A ⇒ aji = −aij

for all i and j

Put j = i, then aii = −aii

If aii

= a + ib, then aii = a − ib

∴ a − ib = −(a + ib) ⇒ 2a = 0 ⇒ a = 0

∴ aii

= ib, which is purely imaginary if b ≠ 0 and 0 if b = 0.

∴ the diagonal elements of a Skew-Hermitian matrix are all purely imaginary or 0 and the elements

equidistant from the main diagonal are conjugates with opposite sign.

Properties: If A and B are complex matrices, then

1. A A

( ) = , 2. A B A B

+ = + 3. a a

A A

=

4. AB A B

= 5. (A*).* = A 6. (A + B).* = A* + B*

7. (aA).* = aA * 8. (AB).* = B*A*

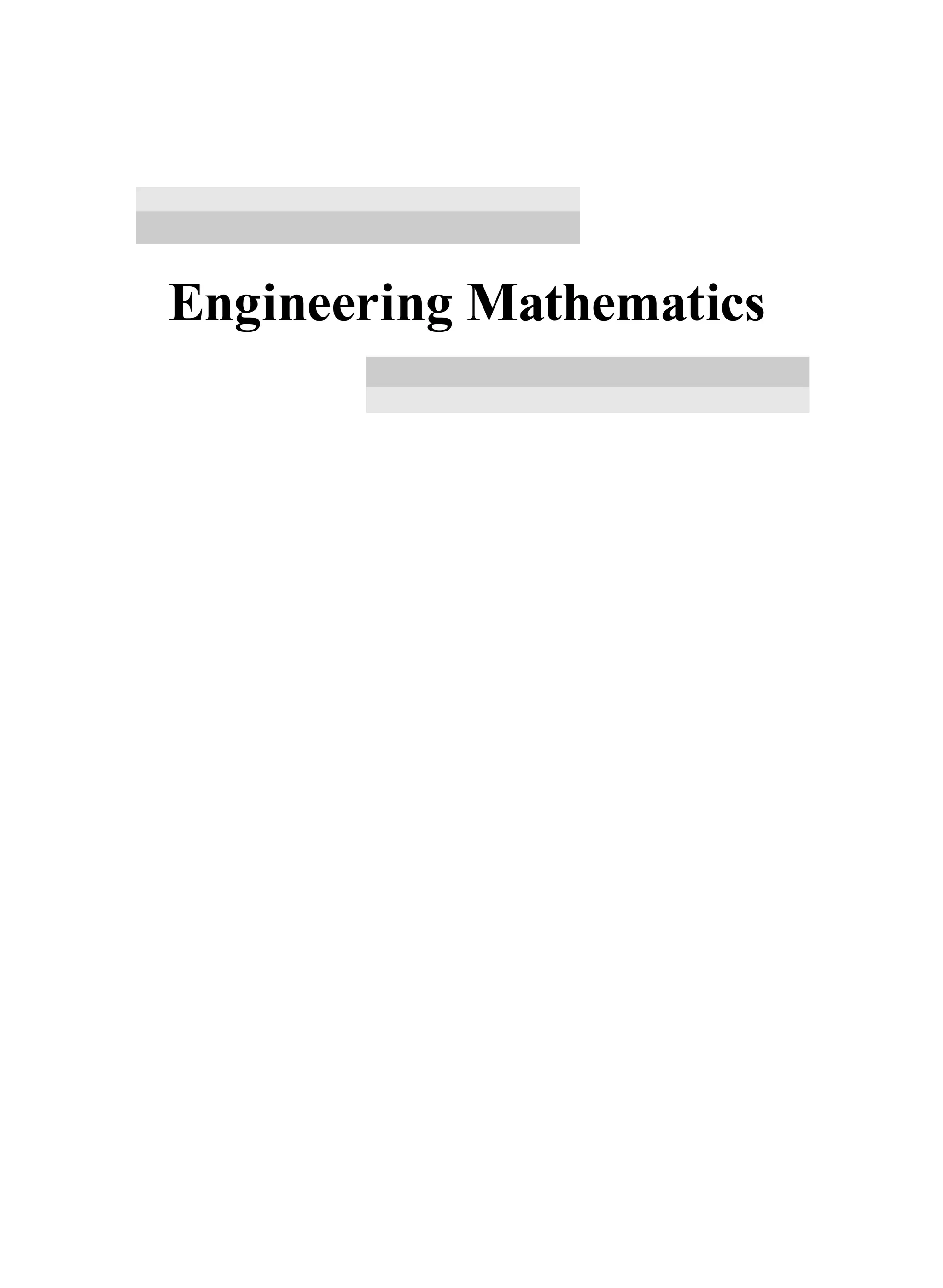

Definition 1.22 Unitary Matrix

A complex square matrix is said to be unitary if AA* = A*A = I

From the definition it is obvious that A* is the inverse of A.

∴ A* = A−1

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 8 5/30/2016 4:34:50 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-45-2048.jpg)

![1.10 ■ Engineering Mathematics

WORKED EXAMPLES

EXAMPLE 1

If A

i i

i i

5

1 2 1

2 2

2 3 1 3

5 4 2

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ , then show that AA* is a Hermitian matrix.

Solution.

Given A

i i

i i

=

+ − +

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 3 1 3

5 4 2

∴ A* = A

i i

i i

T

T

[ ] =

− − −

− − +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 3 1 3

5 4 2

=

− −

−

− − +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 5

3

1 3 4 2

i

i

i i

We have to prove AA* is a Hermitian matrix.

That is to prove (AA*)* = AA*

Now AA

i i

i i

i

i

i i

* =

+ − +

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

− −

−

− − +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 3 1 3

5 4 2

2 5

3

1 3 4 2

=

+ − + ⋅ + − + − − + − + − + − + +

( )( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( ) (

2 2 3 3 1 3 1 3 2 5 3 1 3 4 2

i i i i i i i i

i

i i i i i i i i

)

( ) ( )( ) ( )( ) ( ) ( )( )

− − + ⋅ + − − − − − + − + − +

⎡

⎣

⎢ 5 2 3 4 2 1 3 5 5 4 2 4 2

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎥

=

+ + + + − − − − + +

− + + − − + − +

2 1 9 1 3 10 5 3 4 10 6

10 5 3 4 10 6 25 4

2 2 2

2 2 2

i i i i

i i i i i +

+

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

=

− + −

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

− +

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

2

24 14 2 6

14 2 6 46

24 20 2

20 2 46

2

i

i

i

i ⎦

⎦

⎥ = −

[ ]

{ i2

1

∴ ( *)*

AA

i

i

T

=

− +

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

24 20 2

20 2 46

=

− −

− +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

− +

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

24 20 2

20 2 46

24 20 2

20 2 46

i

i

i

i

T

= AA*

⇒ (AA*)* = AA*

Hence, AA* is a Hermitian matrix.

EXAMPLE 2

Show that every square complex matrix can be expressed uniquely as P + iQ, where P and Q are

Hermitian matrices.

Solution.

Let A be any square complex matrix.

We shall rewrite A as

A A A i

i

A A

= + + −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

1

2

1

2

[ *] ( *)

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 10 5/30/2016 4:34:54 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-47-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.11

Put P A A Q

i

A A

= + = −

1

2

1

2

( *), ( *), then A = P + iQ.

We shall now prove P and Q are Hermitian.

Now, P A A A A A A P

*

( *) ( * ( *)* ( * )

*

= +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ = +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ = + =

1

2

1

2

1

2

∴ P is Hermitian.

and Q A A

i

A A

i

A A

i

A A Q

* ( *) ( * ( *)* [ * ] ( *)

*

= −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ = −

[ ]= − − = − =

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

i

∴ Q is Hermitian.

We shall now prove the uniqueness of the expression A = P + iQ.

If possible, let A = R + iS (1)

where R and S are Hermitian matrices.

∴ R* = R and S* = S

Now, A* = (R + iS)* = R* + (iS)* = R* − iS* = R − iS [by property] (2)

(1) + (2) ⇒ A + A* = 2R ⇒ R =

1

2

( *)

A A P

+ =

(1) − (2) ⇒ A − A* = 2iS ⇒ S =

1

2i

A A Q

( *)

− =

∴ the expression A = P + iQ is unique.

EXAMPLE 3

If A is any square complex matrix, prove that (1) A 1 A* is Hermitian and (ii) A 5 B 1 C, where

B is Hermitian and C is Skew-Hermitian.

Solution.

Given A is a square complex matrix.

(i) Let P = A + A*

∴ P* = (A + A*)* = A* + (A*)* = A* + A = A + A* = P [by property]

∴ P is Hermitian

Hence, A + A* is Hermitian.

To prove (ii): Since A is square complex matrix, we can write A as

A A A A A

= + + −

1

2

1

2

( *) ( *) = B + C

where B A A

= +

1

2

( *) is Hermitian by part (i) and C A A

= −

1

2

( *)

⇒ C A A A A

* ( *) ( * ( *)*

*

= −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ = −

[ ]

1

2

1

2

= − = − − = −

1

2

1

2

[ * ] [ *]

A A A A C

∴ C is Skew- Hermitian.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 11 5/30/2016 4:34:57 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-48-2048.jpg)

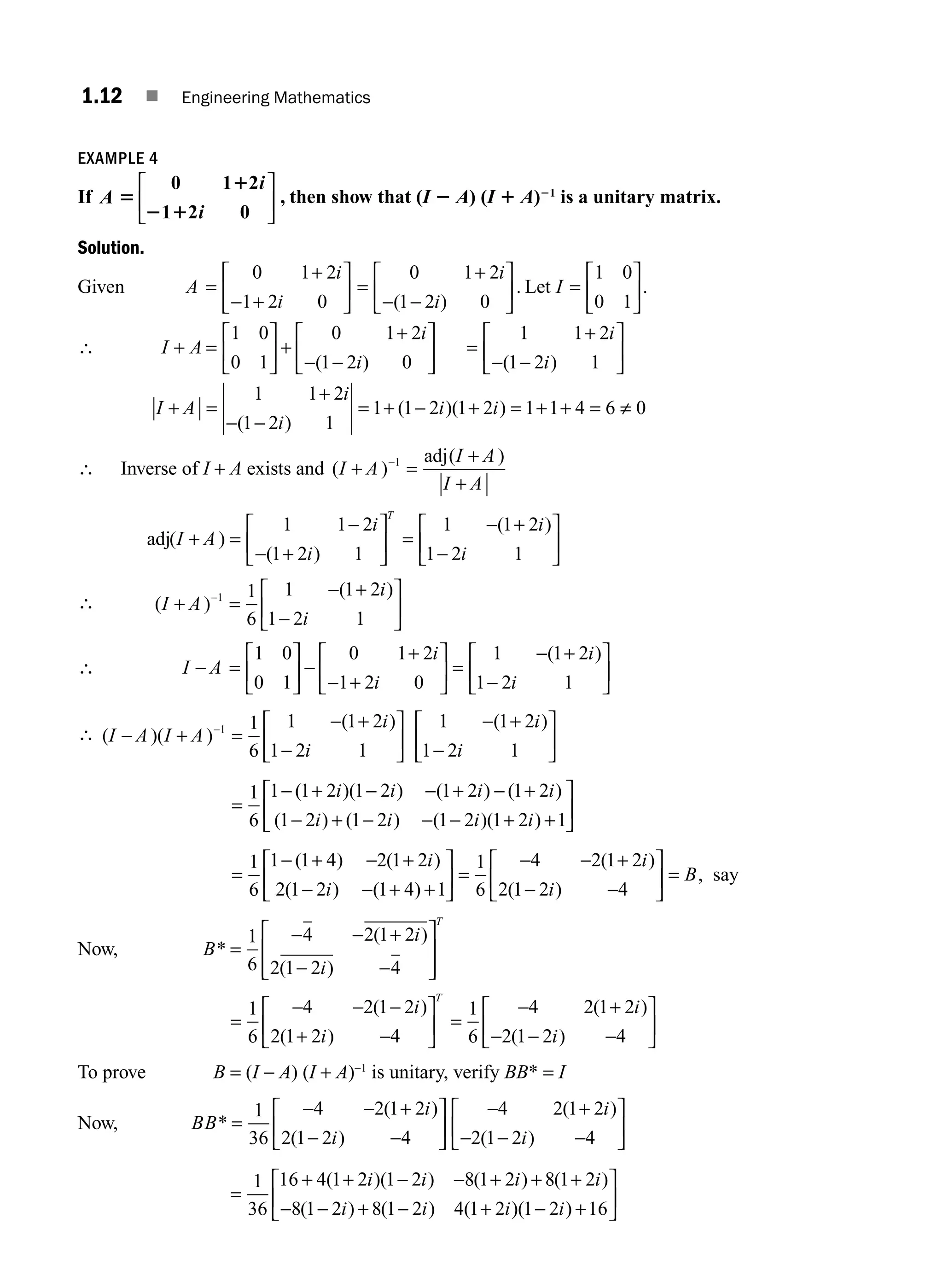

![Matrices ■ 1.13

( )

( )

1

36

16 4 1 4 0

0 4 1 4 6

1

36

36 0

0 36

=

+ +

+ +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

1 0

0 1

I.

∴ B is unitary.

Hence, (I − A)(I + A)−1

is unitary.

Note Another method: To prove B is unitary, verify B* = B−1

EXERCISE 1.1

1. If A B A B

+ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ − =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

7 0

2 5

3 0

0 3

, , find A and B

2. Find x, y, z and w if

3

6

1 2

4

3

x y

z w

x

w

x y

z w

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ +

+

+

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

3. If matrix A has x rows and x +5 columns and B has y rows and 11 − y columns such that both AB and BA

exist, then find x and y.

4. If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 3 4

1 2 3

1 1 2

and B = −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 3 0

1 2 1

0 0 2

, then find AB and BA and test their equality.

5. If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

0

2

2

0

tan

tan

a

a

, show that I A I A

+ = −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

[ ]

cos sin

sin cos

a a

a a

6. If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

cos sin

sin cos

a a

a a

, then verify that AAT

= I2

.

7. If A is a square matrix, then show that A can be expressed as A = P + Q, where P is symmetric and Q is

skew-symmetric.

Hint: Take P

A A

Q

A A

T T

=

+

=

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

2 2

,

8. If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 0 1

2 1 3

1 1 0

and f(x) = x2

− 5x + 6, then find f(A).

9. If A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 1

2 3 0

18 2 10

, then prove that A(adj A) =

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

.

10. Find the inverse of A =

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 0 0

3 3 0

5 2 1

in terms of adj A.

11. Show that A

i i

i i

=

+ − +

+ −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

1

2

1 1

1 1

is unitary.

12. If A and B are orthogonal matrices of the same order, prove that AB is orthogonal.

[Hint: AAT

= I, BBT

= I. Compute AB(AB)T

= A(BBT

)AT

= AAT

= I].

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 13 5/30/2016 4:35:03 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-50-2048.jpg)

![1.14 ■ Engineering Mathematics

13. If A and B are Hermitian matrices of the same order, prove that

(i) A + B is Hermitian (ii) AB + BA is Hermitian

(iii) iA is Skew-Hermitian (iv) AB − BA is Skew-Hermitian

14. Find the inverse of the following matrices.

(i)

2 1 4

3 0 1

1 1 2

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

(ii)

4 3 3

1 0 1

4 4 3

− −

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

15. If A =

3 3 4

2 3 4

0 1 1

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

, then show that A3

= A−1

.

ANSWERS TO EXERCISE 1.1

1. A B

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

5 0

1 4

2 0

1 1

, 2. x = 2, y = 4, z = 1, w = 3 3. x = 3, y = 8

4. AB ≠ BA 8. f A

( ) =

− −

− − −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 3

1 1 10

5 4 4

10. A−

= −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1

1 0 0

1

1

3

0

3

2

3

1

14. (i) A−

=

−

−

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1

1 6 1

5 8 14

3 1 3

(ii) A−

= − −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1

4 3 3

1 0 1

4 4 3

1.3 RANK OF A MATRIX

Let A = [aij

] be an m × n matrix. A matrix obtained by omitting some rows and columns of A is called

a submatrix of A.

The determinant of a square submatrix of order r is called a minor of order r of A.

EXAMPLE 1.22

Consider A =

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 3 4 1

0 3 4 0

3 2 1 2

Omitting the fourth column, we get the submatrix A1

2 3 4

0 3 4

3 2 1

=

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

and A1

2 3 4

0 3 4

3 2 1

=

− −

is a

minor of order 3.

Omitting the first and third columns and the third row, we get the submatrix A2

3 1

3 0

=

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥ and

A2

3 1

3 0

=

−

is a minor of order 2. Since A2 = 3 ≠ 0, it is called a non-vanishing minor of order 2.

But

3 4

3 4

0

= , so it is called a vanishing minor of order 2.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 14 5/30/2016 4:35:06 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-51-2048.jpg)

![1.18 ■ Engineering Mathematics

k R4

1

1

2

5

6

3

2

0

1

2

7

6

3

2

0 0

4

6

0

0 0 0 3

− − −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥ →

∼

R

R R

4 3

+

= B

Given r(A) = 3. So, the number of non-zero rows of B should be 3.

∴ k − 3 = 0 ⇒ k = 3

Definition 1.26 Elementary Matrix

A matrix obtained from a unit matrix by performing a single elementary row (column) transformation

is called an elementary matrix.

Since unit matrices are non-singular square matrices, elementary matrices are also non-singular.

EXAMPLE 1.24

I3

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

z

1 0 0

0 1 1

0 0 1 3 3 2

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥ → +

C C C

This is an elementary matrix.

Similarly,

1 0 0

0 3 0

0 0 1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

got by R2

→ 3R2

is an elementary matrix.

Definition 1.27 Normal form of a Matrix

Any non-zero matrix A of rank r can be reduced by a sequence of elementary transformations to the

form

Ir 0

0 0

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥, where Ir

is a unit matrix of order r.

This form is called a normal form of A.

Other normal forms are Ir

,

Ir

0

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥, [Ir

, 0].

Theorem 1.1

Let A be an m × n matrix of rank r. Then there exist non-singular matrices P and Q of orders m and n

respectively such that PAQ =

Ir 0

0 0

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

Note Each elementary row transformation of A is equivalent to pre multiplying A by the corresponding

elementary matrix. Each elementary column transformation is equivalent to post multiplying A

by the corresponding elementary matrix. So, there exists elementary matrices P1

, P2

, …, Pk

and

Q1

, Q2

, …, Qt

such that

P1

P2

… Pk

A Q1

Q2

… Qt

=

Ir 0

0 0

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 18 5/30/2016 4:35:12 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-55-2048.jpg)

![1.20 ■ Engineering Mathematics

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0 4 4 3

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥ → −

C C C

∼

=

= [ : ]

I3 0

This is the normal form of A and so the r(A) = 3

EXAMPLE 2

Let A 5

2 2

1 1 1

1 1 1

3 1 1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

.Find matrices P and Q such that PAQ is in the normal form.Also find rank

of A.

Solution.

Given A =

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥ ×

1 1 1

1 1 1

3 1 1 3 3

Consider A = I3

AI3

⇒

1 1 1

1 1 1

3 1 1

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

A ⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

Our aim is to reduce the LHS matrix to normal form.

Also row operations to be applied to pre factor and column operations to be applied to post factor.

Apply,

and to post factor

C C C

C C C

2 2 1

3 3 1

1 0 0

1 2 2

3 4 4

→ +

→ +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

1 1 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

A

R R R

R R R

2 2 1

3 3 1

3

1 0 0

0 2 2

0 4 4

1

→ −

→ + −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

( )

and to pre factor

0

0 0

1 1 0

3 0 1

1 1 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

A

R R R

3 3 2

2

1 0 0

0 2 2

0 0 0

1 0 0

1 1 0

1

→ + −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

= −

−

( )

and to pre factor −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 1

1 1 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

A

R R

2 2

1

2

1 0 0

0 1 1

0 0 0

1 0 0

1

2

1

2

0

1 2 1

→

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

= −

− −

and to pre factor

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

A

1 1 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 20 5/30/2016 4:35:16 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-57-2048.jpg)

![1.22 ■ Engineering Mathematics

R R

R R

2 2

3 3

1

3

1

2

1 0 0 0

0 2 2 3

0 2 1 3

1 0

→

→

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

and to pre factor

0

0

4

3

1

3

0

1 0

1

2

1 1 1 2

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

A

⎥

⎥

C C C

4 4 2

3

2

1 0 0 0

0 2 2 0

0 2 1 0

1 0 0

4

3

1

→ +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

= −

and to post factor

3

3

0

1 0

1

2

1 1 1

1

2

0 1 0

3

2

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

A ⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

C C C

3 3 2

1 0 0 0

0 2 0 0

0 2 1 0

1 0 0

4

3

1

3

→ −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

= −

and to post factor

0

0

1 0

1

2

1 1 0

1

2

0 1 1

3

2

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

A ⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

R R R

3 3 2

1 0 0 0

0 2 0 0

0 0 1 0

1 0 0

4

3

1

3

0

→ −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

= −

and to pre factor

1

1

3

1

3

1

2

1 1 0

1

2

0 1 1

3

2

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

A

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

R R

R R

2 2

3 3

1

2

1

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 1 0

1 0

→

→ −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

( )

and to pre factor

0

0

2

3

1

6

0

1

3

1

3

1

2

1 1 0

1

2

0 1 1

3

2

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

A

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⇒ [I3

: 0] = PAQ,

where P Q

= −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

−

−

1 0 0

2

3

1

6

0

1

3

1

3

1

2

1 1 0

1

2

0 1 1

3

2

0 0 1 0

0 0

,

0

0 1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

and the rank of A = 3

Remark: To find the rank of a matrix, the simplest method is to reduce to row echelon form.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 22 5/30/2016 4:35:19 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-59-2048.jpg)

![1.24 ■ Engineering Mathematics

17. Reduce to normal form and find the rank of

0 1 2 1

1 2 3 2

3 1 1 3

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

.

18. If A =

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 2

1 2 3

0 1 1

, then find non-singular matrices P and Q such that PAQ is in normal form and find its

rank.

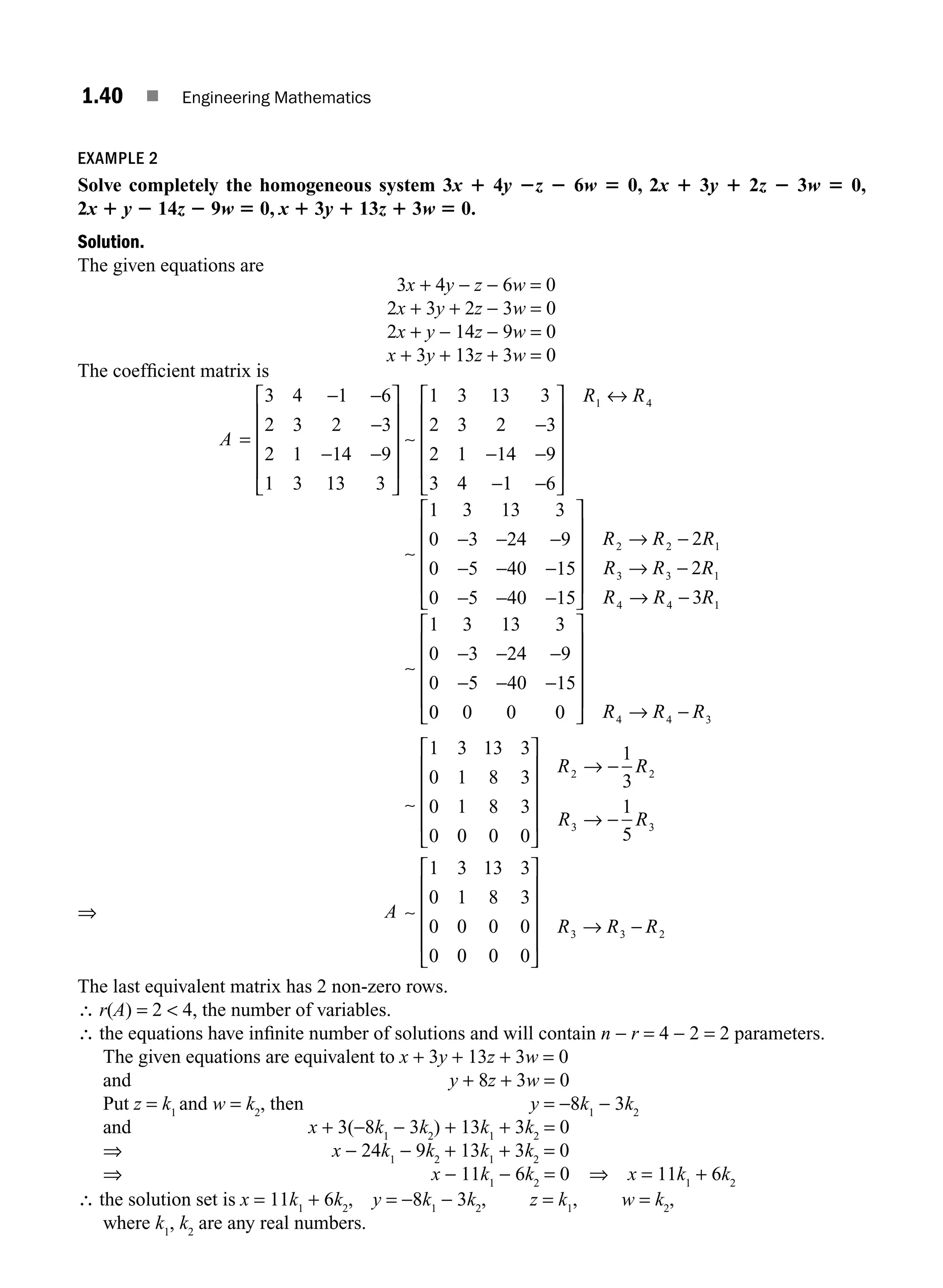

ANSWERS TO EXERCISE 1.2

1. 3 2. 2 3. 3 4. 2 5. 3

6. 3 7. 3 8. 3 9. 3 10. 2

11. 3 12. 3 13. k = 2 14. a = 4, b = 18 15. a = 4, b = 6

16. [I4

, 0], rank = 4 17. [I3

, 0], rank = 3

18. P Q

= −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

− −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 0 0

1 1 0

1 1 1

1 1 1

0 1 1

0 0 1

, and rank = 2.

1.4 SOLUTION OF SYSTEM OF LINEAR EQUATIONS

There are many problems in science and engineering whose solution often depends upon a system of

linear equations.

The equation a1

x1

+ a2

x2

+ … + an

xn

= b is called a non-homogeneous linear equation in n variables

x1

, x2

, …, xn

where b ≠ 0 and at least one ai

≠ 0.

If b = 0, then the equation a1

x1

+ a2

x2

+ … + an

xn

= 0 is called a homogenous linear equation in

x1

, x2

, …, xn

.

1.4.1 Non-homogeneous System of Equations

Consider the system of m linear equations in n variables x1

, x2

, …, xn

a11

x1

+ a12

x2

+ … + a1n

xn

= b1

a21

x1

+ a22

x2

+ … + a2n

xn

= b2

:

am1

x1

+ am2

x2

+ … + amn

xn

= bm

, where at least one bi

≠ 0

If A

a a a

a a a

a a a

B

b

b

b

n

n

m m mn m

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⎡

11 12 1

21 22 2

1 2

1

2

…

…

…

: : : :

,

⎣

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

, ,

X

x

x

xn

1

2

:

then the system of equations can be written as a single matrix equation AX = B.

The matrix A is called the coefficient matrix.

A solution of the system is a set of values of x1

, x2

, …, xn

which satisfy the m equations.

The system of equations is said to be consistent if it has at least one solution.

If the system has no solution, then the system of equations is said to be inconsistent.

The condition for the consistency of the system is given by Rouche’s theorem.

We shall state the theorem without proof.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 24 5/30/2016 4:35:24 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-61-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.25

Theorem 1.2 Rouche’s Theorem The system of linear equations AX = B is consistent if and only if the

coefficient matrix A and the augmented matrix [A, B] have the same rank. That is., r(A) = r([A, B])

Working rule:

Let AX = B represent a system of m equations in n variables.

1. Write down the coefficient matrix A and the augmented matrix [A, B]. Find r(A), r([A, B])

2. If r(A) ≠ r([A, B]), then the system is inconsistent. That is it has no solution.

3. If r(A) = r([A, B]) = n, the number of variables, then the system is consistent with unique solution.

4. If r(A) = r([A, B]) n, the number of variables, then the system is consistent with infinite number

of solutions.

If the rank is r, then in this case the solution set will contain n − r parameters or arbitrary constants.

To get the solutions we assign arbitrary values to n − r variables and write down the solutions in

terms of them.

Forexample,thesystemx+y+z=1,2x−y+3z=−1,2x+5y+z=5isconsistentwithinfinitenumberof

solutions.

Here r = 2, n = 3.

∴ the solution set will contain n − r = 3 − 2 = 1 parameter.

We assign an arbitrary value to one variable, say y.

Put y = k and solve for x and z in terms of k.

The solution set is

x = 4 + 2k, y = k, z = −3 − 3k,

where k is any real number.

Note

If m = n, then A is a square matrix and the system of equations AX = B has unique solution if A is

non-singular. That is., A ≠ 0, then r(A) = number of variables n.

The unique solution is X = A−1

B.

1.4.2 Homogeneous System of Equations

Consider the homogeneous system

a11

x1

+ a12

x2

+ … + a1n

xn

= 0

a21

x1

+ a22

x2

+ … + a2n

xn

= 0

:

am1

x1

+ am2

x2

+ … + amn

xn

= 0

If A

a a a

a a a

a a a

X

x

x

x

n

n

m m mn n

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

=

11 12 1

21 22 2

1 2

1

2

…

…

…

: : : :

,

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

, then the matrix equation is AX = 0.

For this system x1

= 0, x2

= 0, …, xn

= 0 is always a solution. This is called the trivial solution.

If A ≠ 0, the r(A) = n and the only solution is the trivial solution. So, the condition for

non-trivial solution is A = 0 (or r(A) n).

In solving equations we use only row operations.

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 25 5/30/2016 4:35:26 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-62-2048.jpg)

![1.26 ■ Engineering Mathematics

1.4.3 Type 1: Solution of Non-homogeneous System of Equations

WORKED EXAMPLES

(A) Non-homogeneous system with unique solution

EXAMPLE 1

Test for consistency and solve 2x 2 y 1 z 5 7, 3x 1 y 2 5z 5 13, x 1 y 1 z 5 5.

Solution.

The given equations are

x + y + z = 5

2x − y + z = 7

3x + y − 5z = 13

We have rearranged the equation for convenience in reducing to row echelon form.

The coefficient matrix is A = −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 1

2 1 1

3 1 5

and the augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

:

A B = −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

− − −

− − −

⎡

⎣

1 1 1 5

2 1 1 7

3 1 5 13

1 1 1 5

0 3 1 3

0 2 8 2

∼ ⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

R R R

R R R

2 2 1

3 3 1

2

3

∼

∼

1 1 1 5

0 1

1

3

1

0 1 4 1

1

3

1

2

1 1 1 5

0 1

1

3

2 2

3 3

:

:

:

:

:

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→

R R

R R

1

1

0 0

11

3

0 3 3 2

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ +

: R R R

From the last matrix, we find

A ∼

1 1 1

0 1

1

3

0 0

11

3

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 26 5/30/2016 4:35:27 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-63-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.27

The number of non-zero rows in the equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 3.

∴ r(A) = 3, r([A, B]) = 3

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 3, the number of variables.

So, the equations are consistent with unique solution.

From the reduced matrix [A, B], we find the given equations are equivalent to

x + y + z = 5, y +

1

3

z = 1 and −

11

3

z = 0 ⇒ z = 0

∴ y = 1 and x + 1 + 0 = 5 ⇒ x = 4.

So, the unique solution is x = 4, y = 1, z = 0.

EXAMPLE 2

Test for the consistency and solve x 1 2y 1 z 5 3, 2x 1 3y 1 2z 5 5, 3x 2 5y 1 5z 5 2,

3x 1 9y 2 z 5 4.

Solution.

The given equations are

x + 2y + z = 3

2x + 3y + 2z = 5

3x − 5y + 5z = 2

3x + 9y − z = 4.

The coefficient matrix is A =

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 1

2 3 2

3 5 5

3 9 1

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

:

A B = ∼

1 2 1 3

2 3 2 5

3 5 5 2

3 9 1 4

1 2 1 3

0 1 0 1

0 11 2

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

− −

− :

:

:

:

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

→ −

−

7

0 3 4 5

2

3

3

1 2 1 3

0

2 2 1

3 3 1

4 4 1

R R R

R R R

R R R

∼

1

1 0 1

0 0 2 4

0 0 4 8

11

3

1 2 1 3

0 1

3 3 2

4 4 2

:

:

:

:

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ +

−

R R R

R R R

∼

0

0 1

0 0 1 2

0 0 1 2

1

2

1

4

3 3

4 4

:

:

:

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→

→ −

R R

R R

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 27 5/30/2016 4:35:28 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-64-2048.jpg)

![1.28 ■ Engineering Mathematics

⇒ [ , ]

:

:

:

:

A B

R R R

∼

1 2 1 3

0 1 0 1

0 0 1 2

0 0 0 0 4 4 3

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

From this last matrix we find

A ∼

1 2 1

0 1 0

0 0 1

0 0 0

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

The number of non-zero rows in the equivalent matrices of A and [A B] are 3.

∴ r(A) = 3, r([A, B]) = 3

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 3, the number of variables.

So, the equations are consistent with unique solution

From the reduced matrix [A, B], we find the given equations are equivalent to

x + 2y + z = 3, −y = −1 and z = 2

∴ y = 1, z = 2 and so x + 2 ⋅ 1 + 2 = 3 ⇒ x = −1

So, the unique solution is x = −1, y = 1, z = 2.

EXAMPLE 3

Solve x2

yz 5 e, xy2

z3

5 e, x3

y2

z 5 e using matrices.

Solution.

The given equations are

x2

yz = e (1)

xy2

z3

= e (2)

x3

y2

z = e (3)

Taking logarithm to the base e on both sides of (1), (2) and (3), we get

and

log log log log log

log log log

lo

e e e e e

e e e

x yz e x y z

x y z

2 2

1

2 1

= ⇒ + + =

⇒ + + =

g

g log log log log

log log log

e e e e e

e e

xy z e x y z

x y z e x

2 3

3 2

2 3 1

3

= ⇒ + + =

= ⇒ + 2

2 1

log log

e e

y z

+ =

For simplicity, put x1

= loge

x, y1

= loge

y, z1

= loge

z

∴ the equations are 2x1

+ y1

+ z1

= 1

x1

+ 2y1

+ 3z1

= 1

3x1

+ 2y1

+ z1

= 1

The coefficient matrix is A =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 1 1

1 2 3

3 2 1

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 28 5/30/2016 4:35:29 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-65-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.29

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

A B =

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 1 1 1

1 2 3 1

3 2 1 1

∼

∼

1 2 3 1

2 1 1 1

3 2 1 1

1 2 3 1

0 3 5 1

0 4 8 2

1 2

:

:

:

:

:

:

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

↔

− − −

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

R R

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

R R R

R R R

2 2 1

3 3 1

2

3

⇒ − − −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

A B

1 2 3 1

0 3 5 1

0 0

4

3

2

3

[ , ]

:

:

:

∼

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥ → −

R R R

3 3 2

4

3

From the last matrix, we find A ∼

1 2 3

0 3 5

0 0

4

3

− −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

The number of non-zero rows in the equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 3.

∴ r(A) = 3, r([A, B]) = 3

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 3, the number of variables.

So, the equations are consistent with unique solution.

From the reduced matrix [A, B], we find that the given equations are equivalent to

x1

+ 2y1

+ 3z1

= 1 (4)

−3y1

− 5z1

= −1 (5)

and − = − ⇒ =

4

3

2

3

1

2

1 1

z z

Substituting in (5), we get

− − ⋅ = − ⇒ = − = − ⇒ = −

3 5

1

2

1 3 1

5

2

3

2

1

2

1 1 1

y y y

Substituting in (4) we get

⇒

∴

x x x

x x x e

e

1 1 1

1

1

2

1

2

3

1

2

1

1

2

1 1

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

+ −

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎞

⎠

⎟ + ⋅ = ⇒ + = ⇒ = − =

= ⇒ = ⇒ =

log 2

2

1

1

2

1

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

1

2

1

2

=

= − ⇒ = − ⇒ = =

= ⇒ = ⇒ = =

−

e

y y y e

e

z z z e e

e

e

log

log

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 29 5/30/2016 4:35:31 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-66-2048.jpg)

![1.30 ■ Engineering Mathematics

So, the unique solution is

x e y

e

z e

= = =

, ,

1

.

(B) Non-homogeneous system with infinite number of solutions

EXAMPLE 4

By investigating the rank of relevant matrices, show that the following equations possess a one

parameter family of solutions: 2x 2 y 2 z 5 2, x 12y 1 z 5 2, 4x 2 7y 2 5z 5 2.

Solution.

The given equations are

x +2y + z = 2

2x − y − z = 2

4x − 7y − 5z = 2

The coefficient matrix is A = − −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 1

2 1 1

4 7 5

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

:

A B = − −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

− − −

− − −

1 2 1 2

2 1 1 2

4 7 5 2

1 2 1 2

0 5 3 2

0 15 9 6

∼

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

− − −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

R R R

R R R

2 2 1

3 3 1

2

4

1 2 1 2

0 5 3 2

0 0 0 0

∼

:

:

: R

R R R

3 3 2

3

→ −

From the last matrix we find A ∼

1 2 1

0 5 3

0 0 0

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

The number of non-zero rows of equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 2

∴ r(A) = 2, r([A, B]) = 2

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 2 the number of variables 3.

So, the equations are consistent with infinite number of solutions involving one parameter,

since n − r = 3 − 2 = 1.

From the reduced matrix [A, B], we find that the given equations are equivalent to

x + 2y + z = 2 (1)

− 5y − 3z = − 2 ⇒ 5y + 3z = 2 (2)

Assign arbitrary value to one of the variables.

Put z = k in (2) ∴ 5y + 3k = 2 ⇒ y

k

=

−

2 3

5

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 30 5/30/2016 4:35:33 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-67-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.31

Substituting in (1), we get,

x

k

k

x

k

k

k k k

+

−

+ =

= −

−

− =

− + −

=

+

2 2 3

5

2

2

2 2 3

5

10 4 6 5

5

6

5

( )

( )

∴ the solution set is x k

= +

1

5

6

( ), y k z k

= − =

1

5

2 3

( ), , where k is any real number.

EXAMPLE 5

Solve, if the equations are consistent: x 2 y 1 2z 5 1, 3x 1 y 1 z 5 4, x 1 3y 23z 5 2,

5x 2 y 1 5z 5 6.

Solution.

The given equations are

x − y + 2z = 1

3x + y + z = 4

x + 3y − 3z = 2

5x − y + 5z = 6

The coefficient matrix is A =

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 1 2

3 1 1

1 3 3

5 1 5

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

:

A B =

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

−

−

1 1 2 1

3 1 1 4

1 3 3 2

5 1 5 6

1 1 2 1

0 4 5 1

0 4 5

∼

:

:

:

:

1

0 4 5 1

3

5

1 1 2 1

0 4 5

2 2 1

3 3 1

4 4 1

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

→ −

−

−

R R R

R R R

R R R

∼

:

:

:

:

1

0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0

3 3 2

4 4 2

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

R R R

R R R

From the last matrix, we find A ∼

1 1 2

0 4 5

0 0 0

0 0 0

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

The number of non-zero rows of the equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 2.

⇒

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 31 5/30/2016 4:35:34 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-68-2048.jpg)

![1.32 ■ Engineering Mathematics

∴ r(A) = 2, r([A, B]) = 2

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 2 3, the number of variables.

So, the equations are consistent with infinite number of solutions involving one parameter,

since n − r = 3 − 2 = 1.

From reduced matrix [A, B], we find that the given equations are equivalent to

x − y + 2z = 1 (1)

4y − 5z = 1 (2)

Put z = k, in (2) then 4y − 5k = 1 ⇒ y

k

=

+

1 5

4

Substituting in (1), we get

x

k

k x

k

k

k k k

−

1 5

4

2 1 1

1 5

4

2

4 1 5 8

4

5 3

4

+

+ = ⇒ = +

+

− =

+ + −

=

−

∴ the solution set is

x

k

y

k

z k

=

−

=

+

=

5 3

4

1 5

4

, , , where k is any real number.

EXAMPLE 6

Test the consistency of the system of equations and solve, if consistent: x1

1 2x2

2 x3

2 5x4

5 4,

x1

1 3x2

2 2x3

2 7x4

5 5, 2x1

2 x2

1 3x3

5 3.

Solution.

The given equations are

x1

+ 2x2

− x3

− 5x4

= 4

x1

+ 3x2

− 2x3

− 7x4

= 5

2x1

− x2

+ 3x3

+ 0x4

= 3

The coefficient matrix is A =

− −

− −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 1 5

1 3 2 7

2 1 3 0

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

A B =

− −

− −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

− −

− −

−

1 2 1 5 4

1 3 2 7 5

2 1 3 0 3

1 2 1 5 4

0 1 1 2 1

0

∼

5

5 5 10 5 2

1 2 1 5 4

0 1 1 2 1

0 0 0 0 0

2 2 1

3 3 1

:

:

:

:

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

− −

− −

R R R

R R R

∼

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥ → +

R R R

3 3 2

5

From the last matrix, we find

A ∼

1 2 1 5

0 1 1 2

0 0 0 0

− −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 32 5/30/2016 4:35:36 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-69-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.33

The number of non-zero rows of the equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 2.

∴ r(A) = 2, r([A, B]) = 2

⇒ r(A) = r([A, B]) = 2 4, the number of variables.

So, the equations are consistent with infinite number of solutions containing two parameters,

since n − r = 4 − 2 = 2.

From the reduced matrix of [A, B] we find that the given equations are equivalent to

x1

+ 2x2

− x3

− 5x4

= 4 (1)

and x2

− x3

− 2x4

= 1 (2)

Put x3

= k1

, x4

= k2

, then (2) ⇒ x2

− k1

− 2k2

= 1 ⇒ x2

= 1 + k1

+ 2k2

Substituting in (1), we get

x1

+ 2(1 + k1

+ 2k2

) − k1

− 5k2

= 4

⇒ x1

+ 2 + 2k1

+ 4k2

− k1

− 5k2

= 4

⇒ x1

+ k1

− k2

= 2 ⇒ x1

= 2 − k1

+ k2

∴ the solution set is

x1

= 2 − k1

+ k2

, x2

= 1 + k1

+ 2k2

, x3

= k1

, x4

= k2

, where k1

, k2

are any real numbers.

(C) Non-homogeneous system with no solution

EXAMPLE 7

Examine for the consistency of the following equations 2x 1 6y 1 11 5 0, 6x 1 20y 2 6z 1 3 5 0,

6y 2 18z 1 1 5 0.

Solution.

The given equations are

2x + 6y + 0z = −11

6x + 20y − 6z = −3

0x + 6y − 18z = −1

The coefficient matrix is A = −

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

2 6 0

6 20 6

0 6 18

The augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

A B =

−

− −

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

−

− −

2 6 0 11

6 20 6 3

0 6 18 1

1 3 0

11

2

6 20 6 3

0 6

∼

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→

18 1

1

2

1 1

:

R R

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 33 5/30/2016 4:35:37 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-70-2048.jpg)

![1.34 ■ Engineering Mathematics

−

−

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

1 3 0

11

2

0 2 6 30

0 6 18 1

:

:

:

∼

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

R R R

2 2 1

6

⇒ [ , ]

:

:

:

A B

R R R

∼

1 3 0

11

2

0 2 6 30

0 0 0 91 3

3 3 2

−

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥ → −

From the last matrix, we find A ∼

1 3 0

0 2 6

0 0 0

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

The number of non-zero rows in the equivalent matrices of A and [A, B] are 2 and 3 respectively.

∴ r(A) = 2, r([A, B]) = 3

⇒ r(A) ≠ r([A, B]).

Hence, the equations are inconsistent and the system has no solution.

1.4.4 Type 2: Solution of Non-homogeneous Linear Equations Involving Arbitrary

Constants

WORKED EXAMPLES

EXAMPLE 1

Show that the system of equations 3x 2 y 1 4z 5 3, x 1 2y 2 3z 5 22, 6x 1 5y 1 lz 5 23 has

at least one solution for any real number l. Find the set of solutions when l 5 25.

Solution.

The given equations are

x + 2y − 3z = −2,

3x − y + 4z = 3

6x + 5y + lz = −3

The coefficient matrix is A =

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

1 2 3

3 1 4

6 5 l

and the augmented matrix is

[ , ]

:

:

:

:

:

:

A B =

− −

−

−

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

− −

−

− +

1 2 3 2

3 1 4 3

6 5 3

1 2 3 2

0 7 13 9

0 7 18

l l

∼

9

9

3

6

2 2 1

3 3 1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

→ −

→ −

R R R

R R R

M01_ENGINEERING_MATHEMATICS-I _CH01_Part A.indd 34 5/30/2016 4:35:38 PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/p-240106174416-34a05fe0/75/P-Sivaramakrishna-Das-C-Vijayakumari-Engineering-Mathematics-Pearson-Education-2017-pdf-71-2048.jpg)

![Matrices ■ 1.35

⇒

1 2 3 2

0 7 13 9

0 0 5 0

− −

−

+

⎡

A B

[ , ]

:

:

:

∼

l

⎣

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥ → −

R R R

3 3 2

From the last matrix we find A ∼

1 2 3

0 7 13

0 0 5

−

−

+

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

l