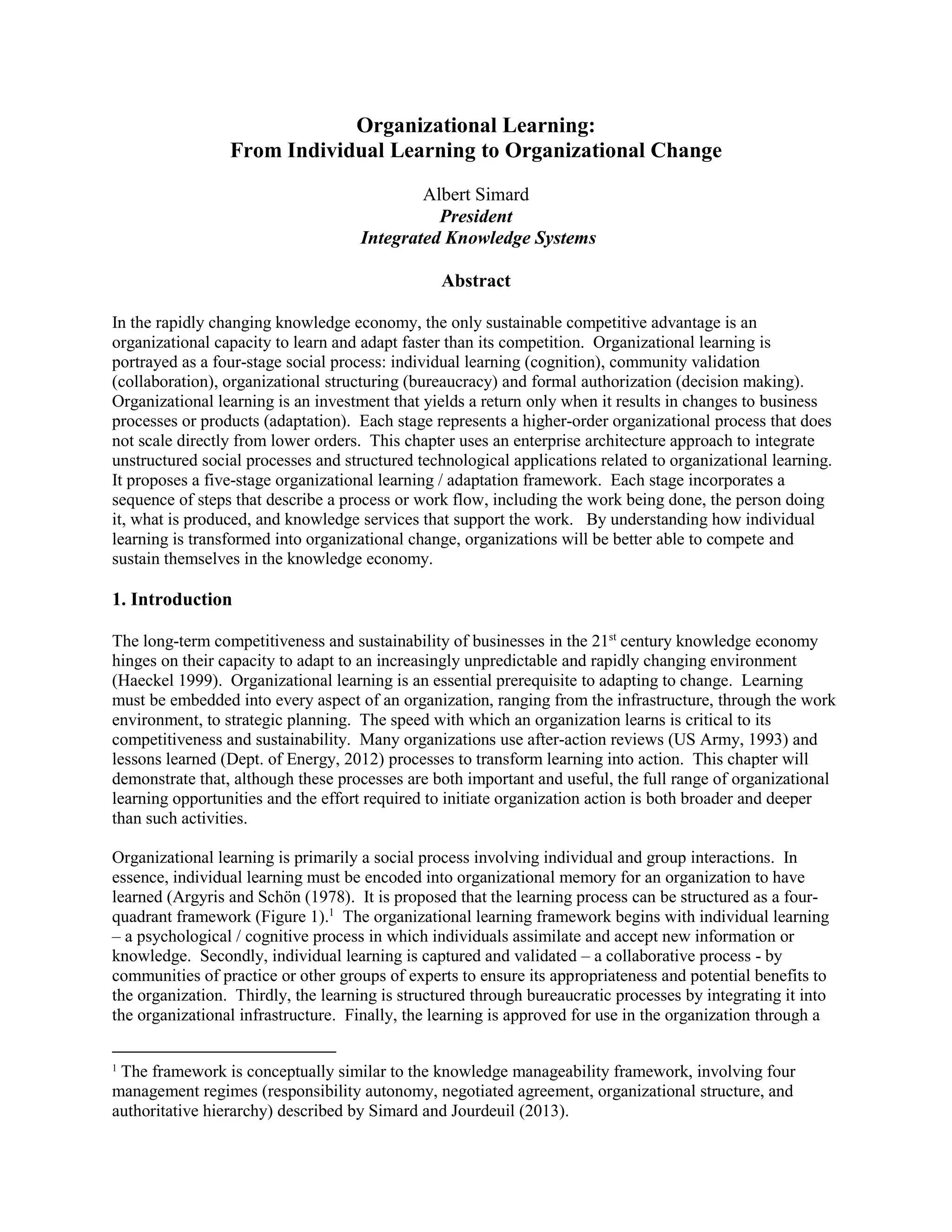

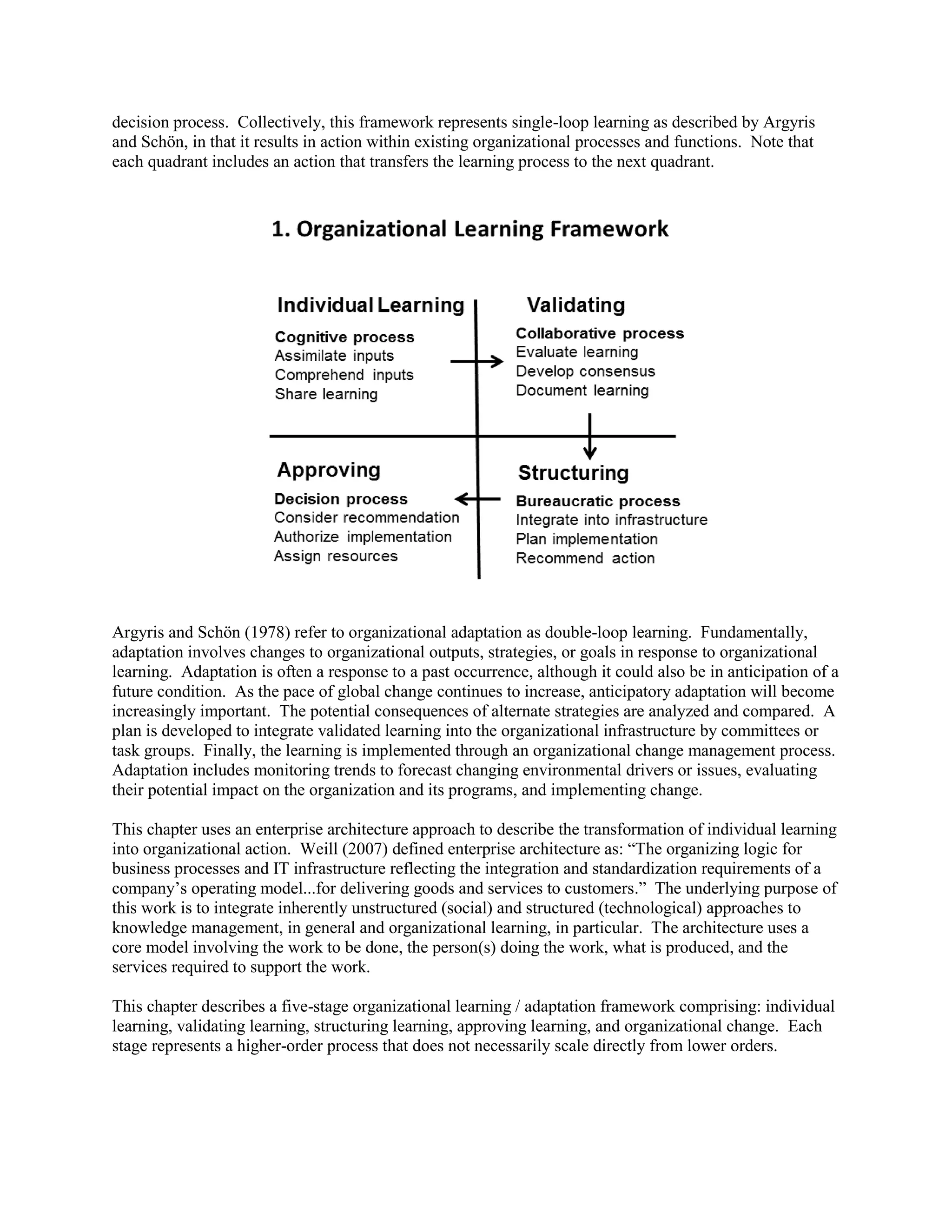

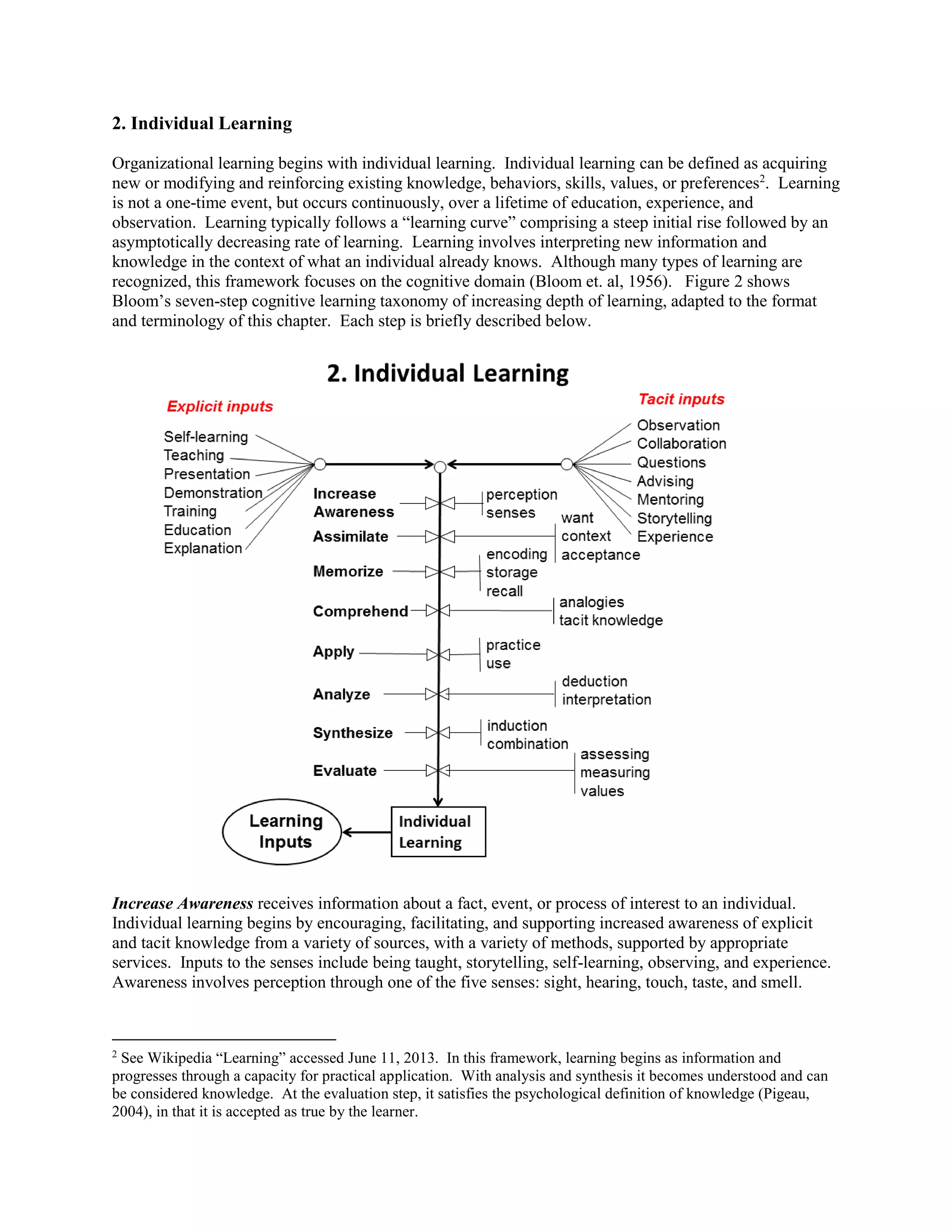

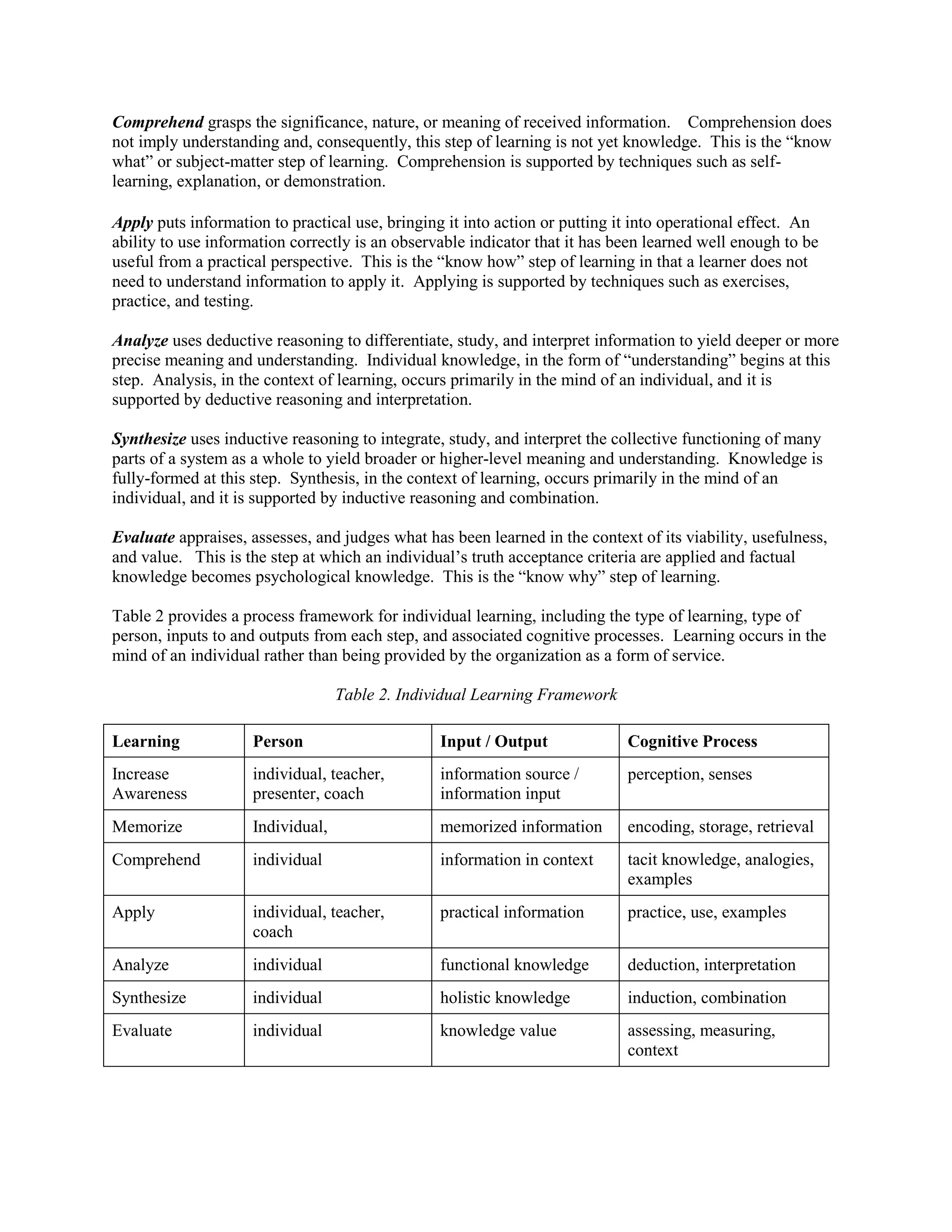

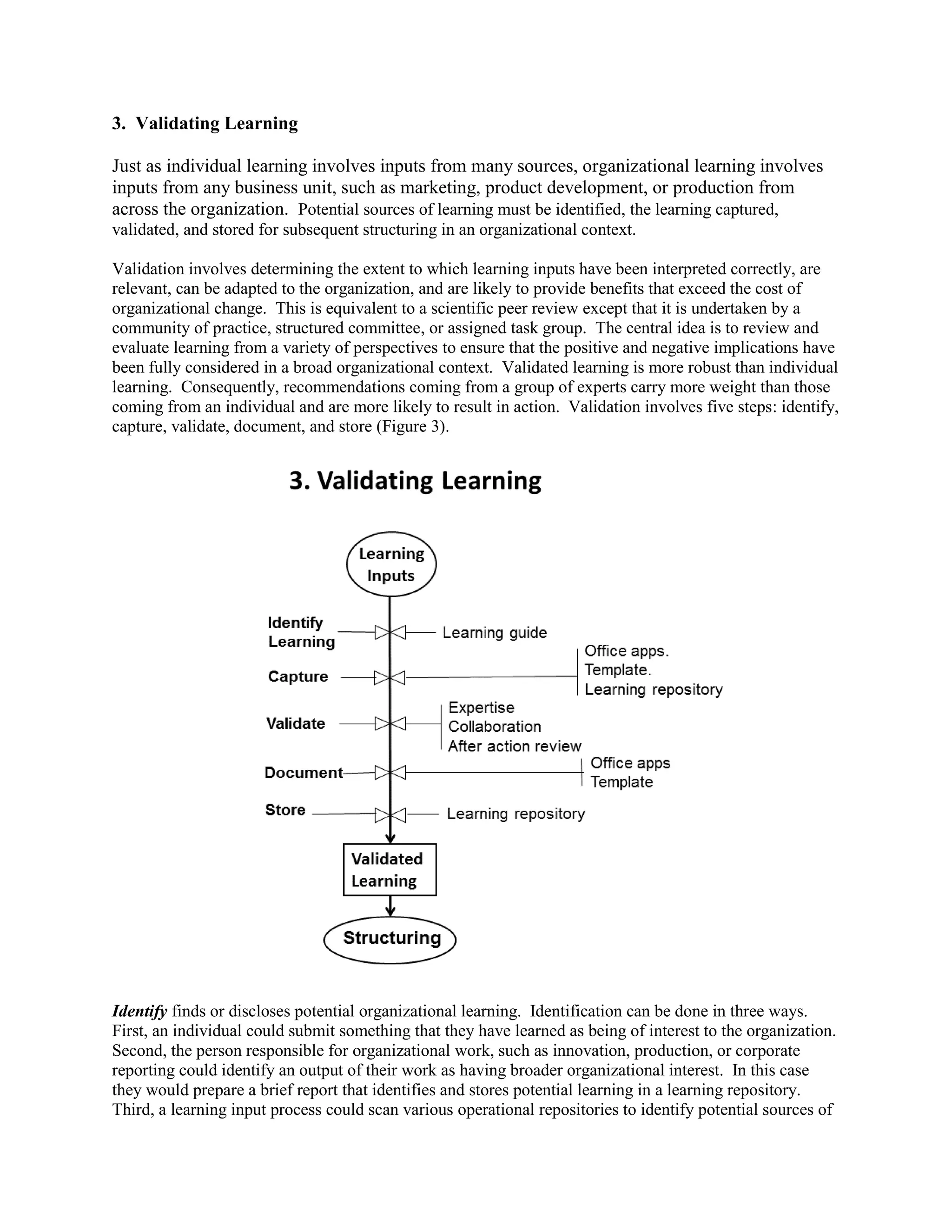

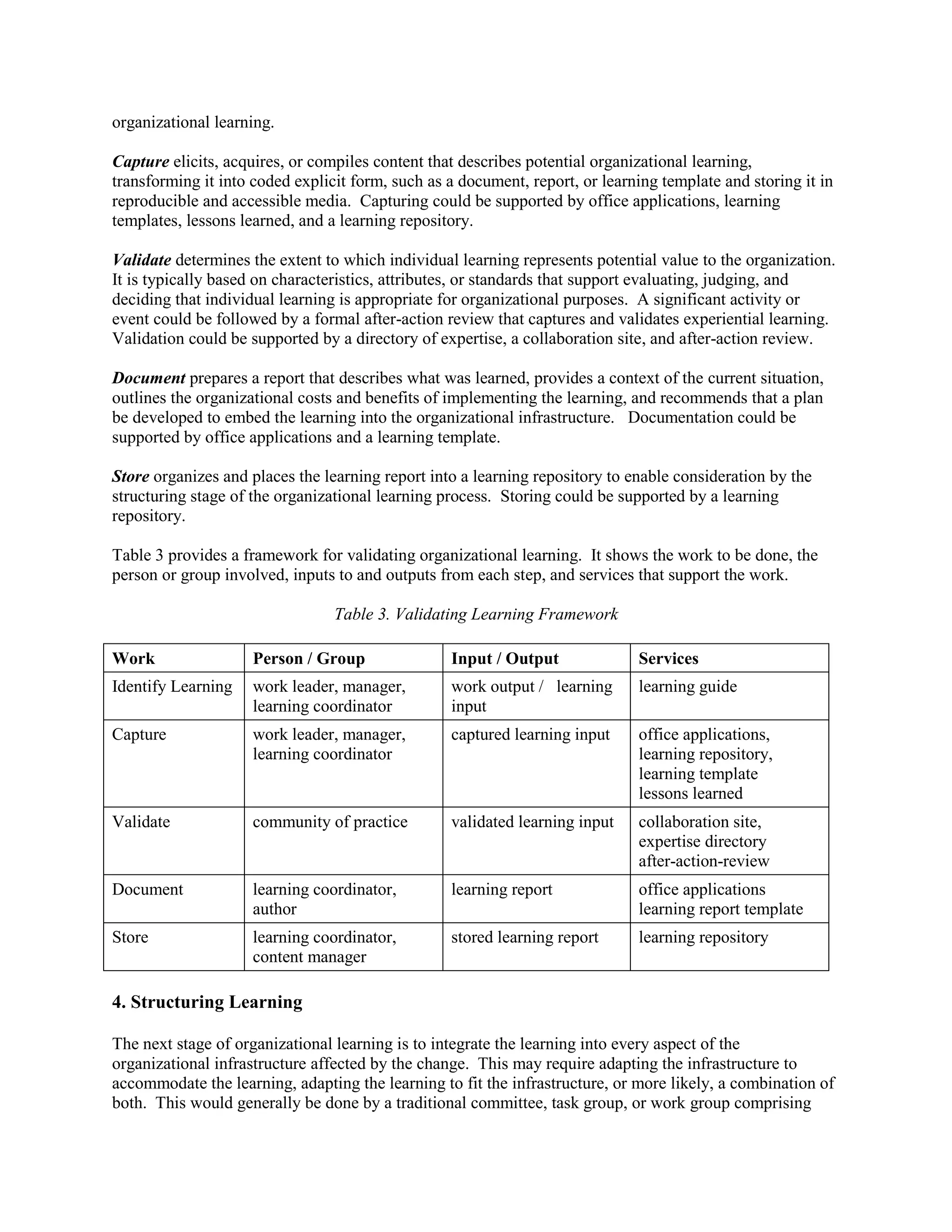

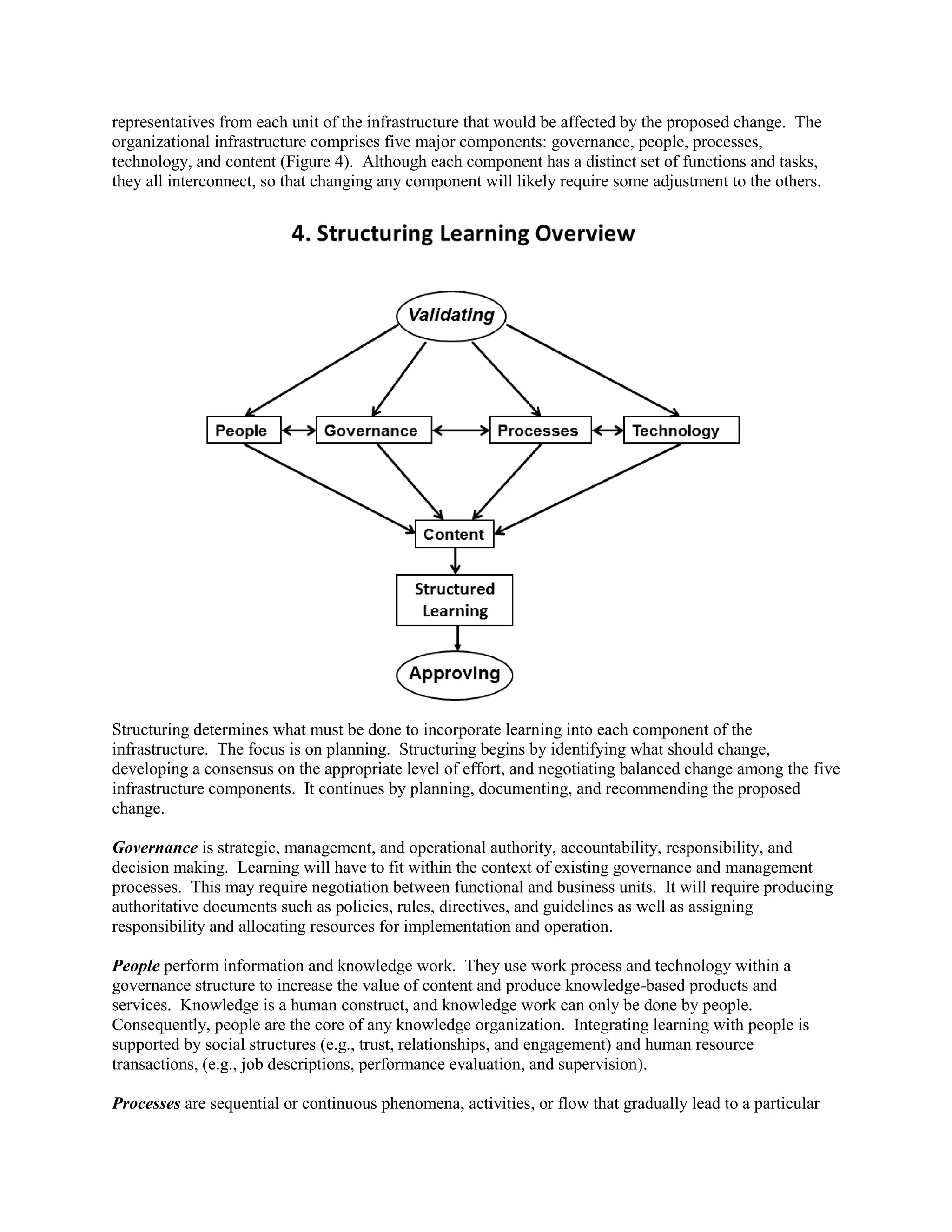

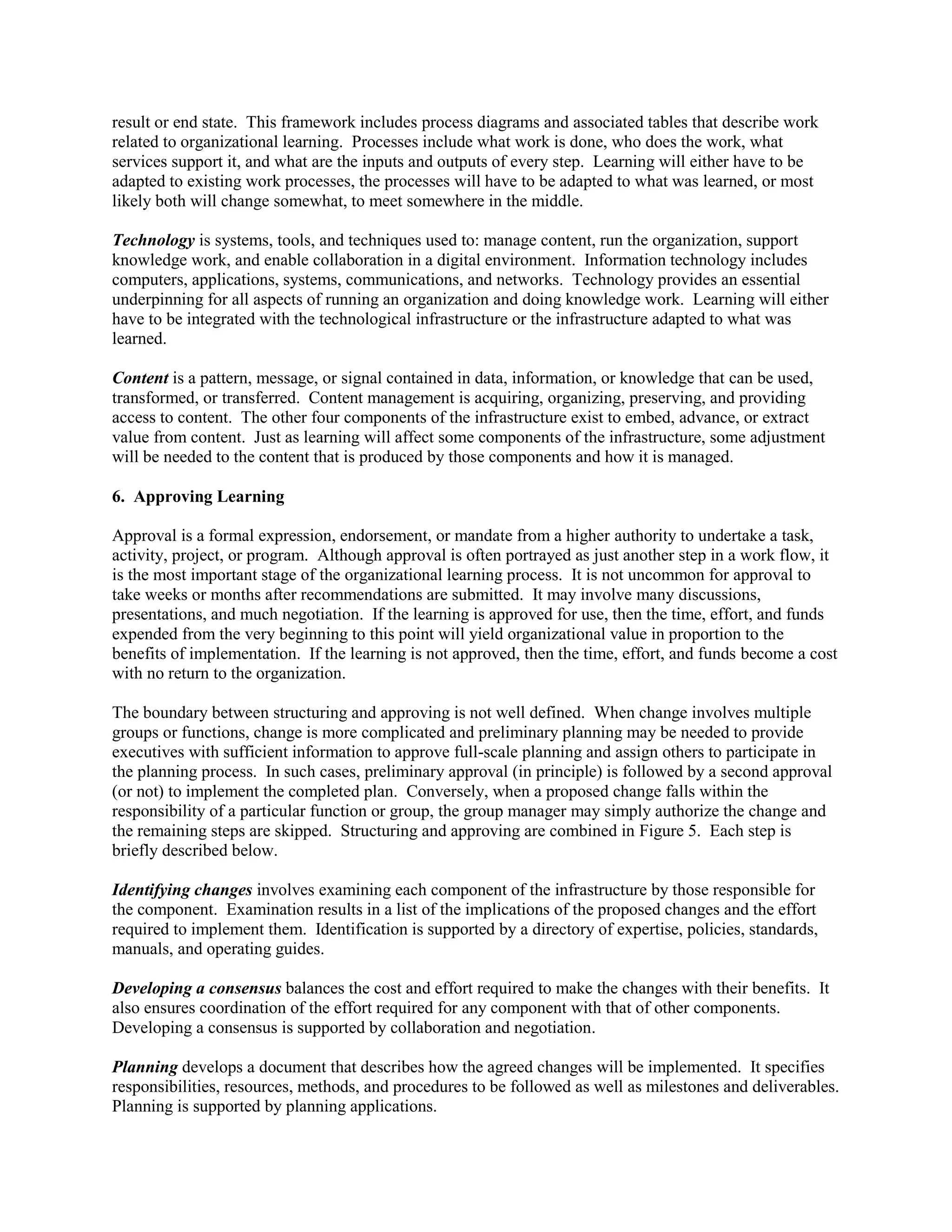

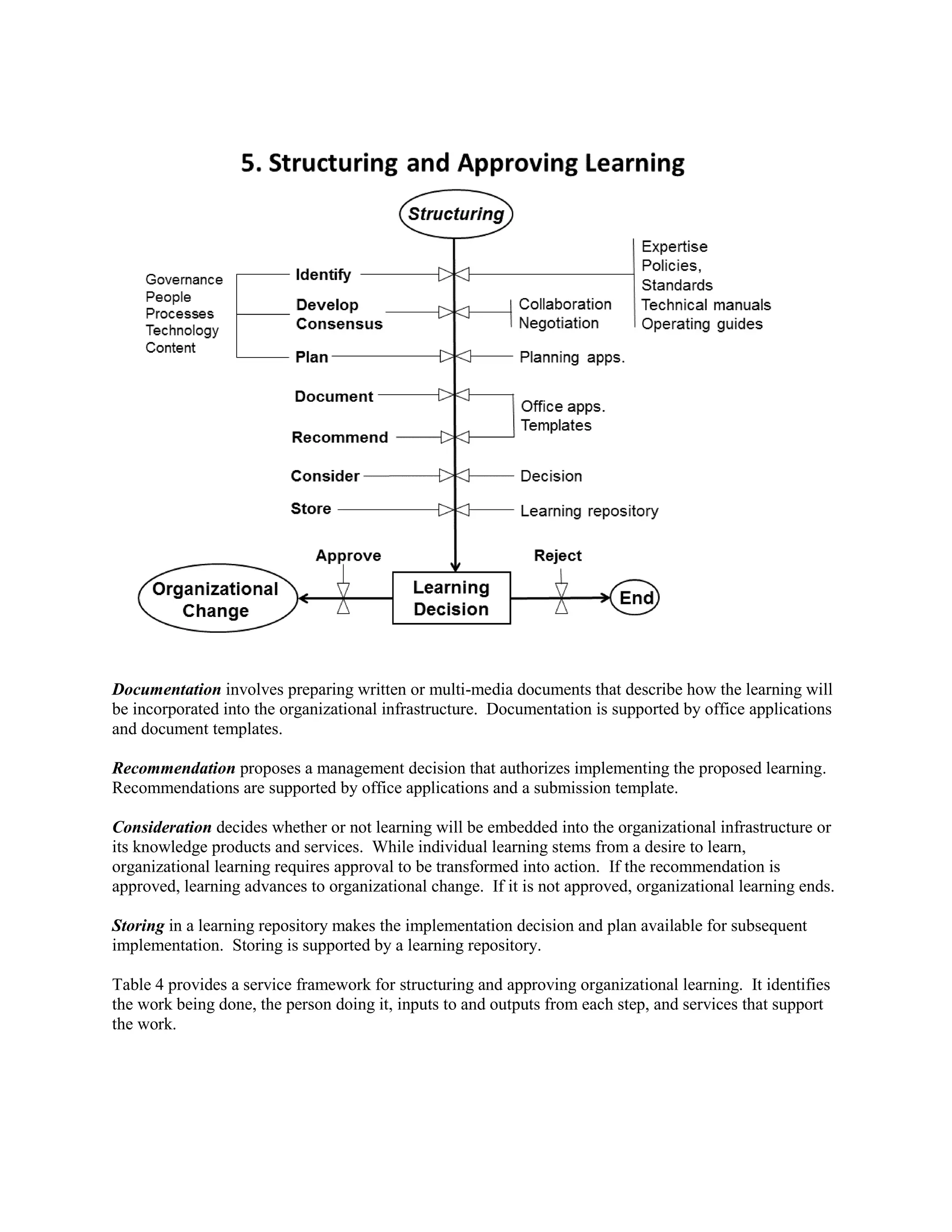

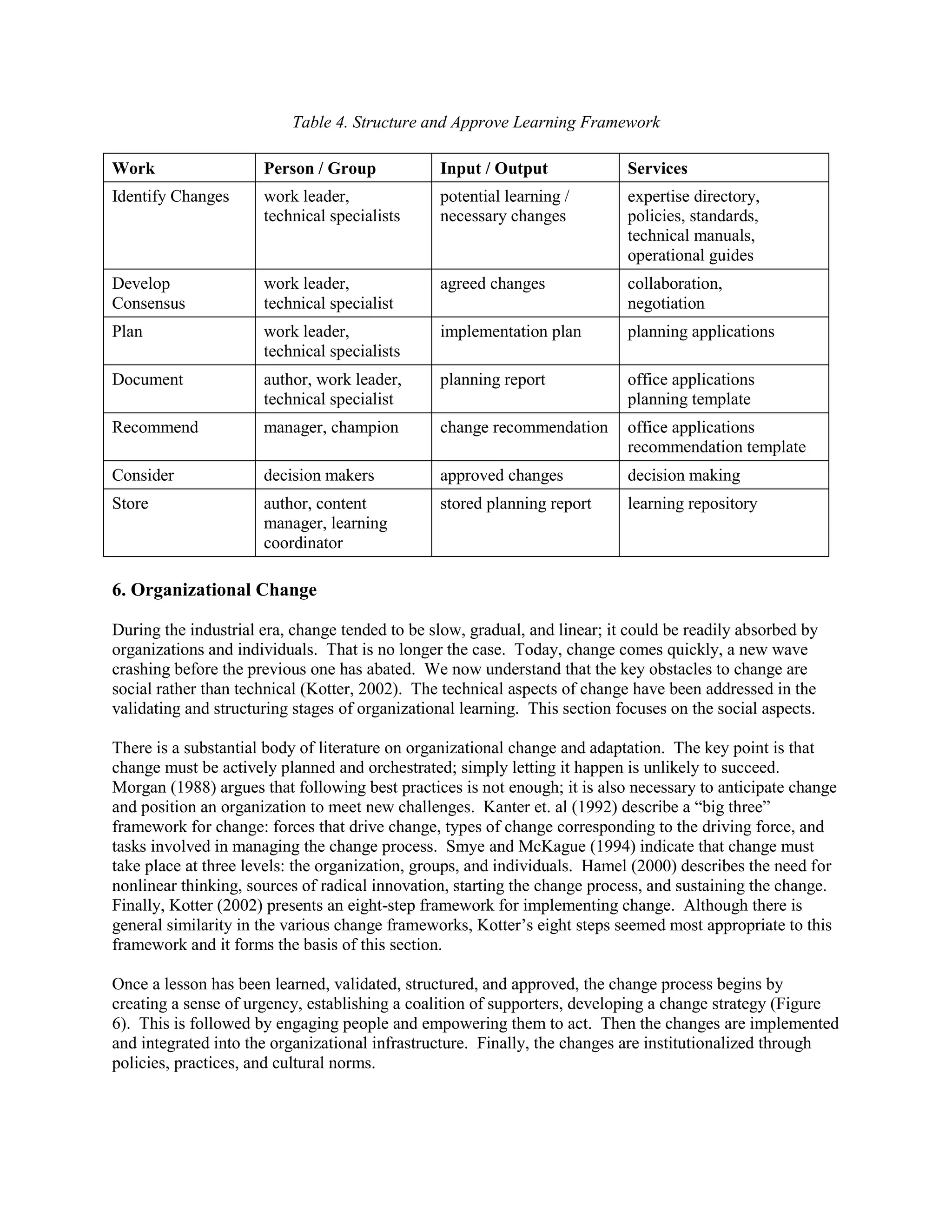

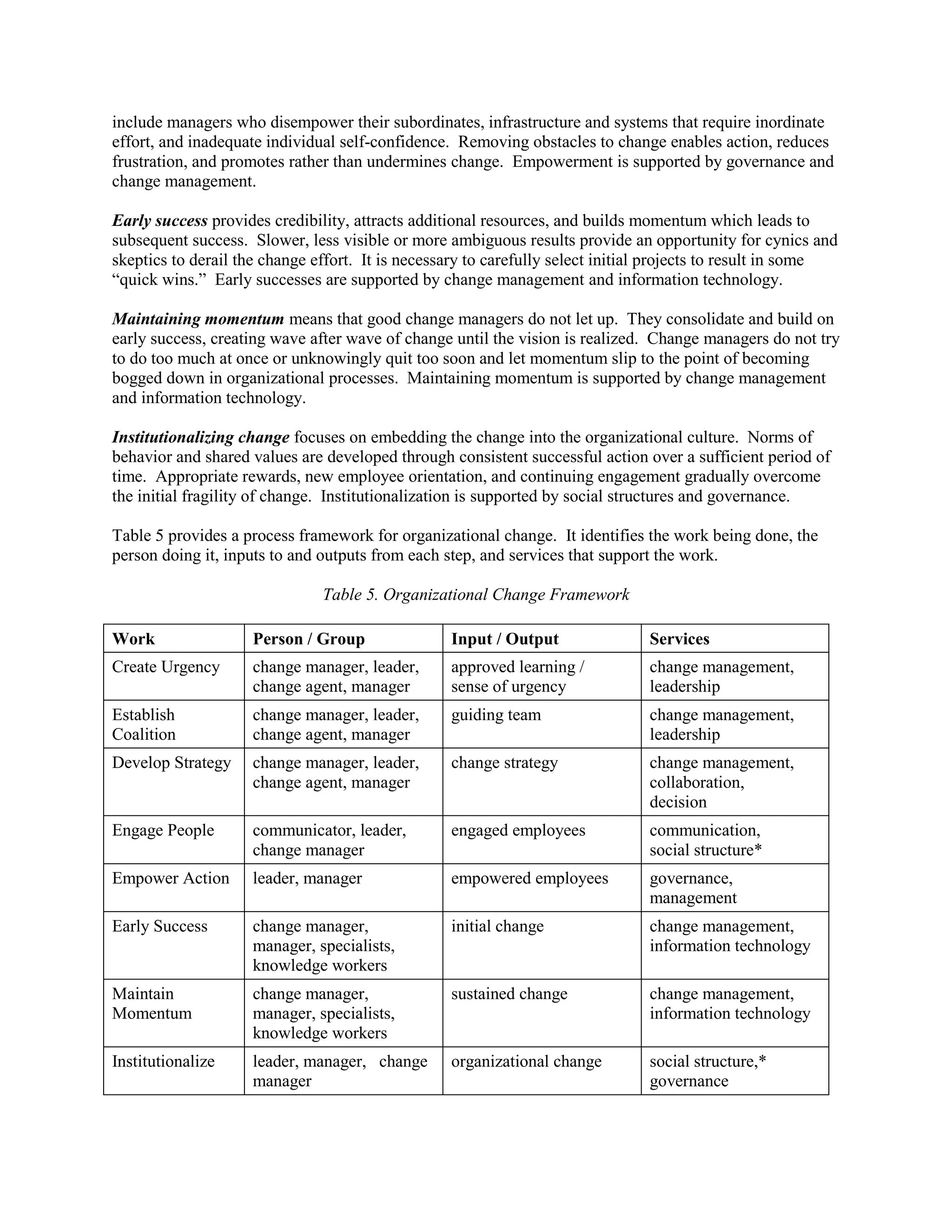

The document discusses organizational learning as a crucial capability for businesses to adapt in the fast-paced knowledge economy, outlining a four-stage process: individual learning, community validation, organizational structuring, and formal authorization. It emphasizes that learning must be integrated into all organizational facets to foster change, supported by a five-stage framework that includes adapting and implementing learning effectively. By transforming individual knowledge into organizational change, businesses can enhance their competitive advantage and sustainability.