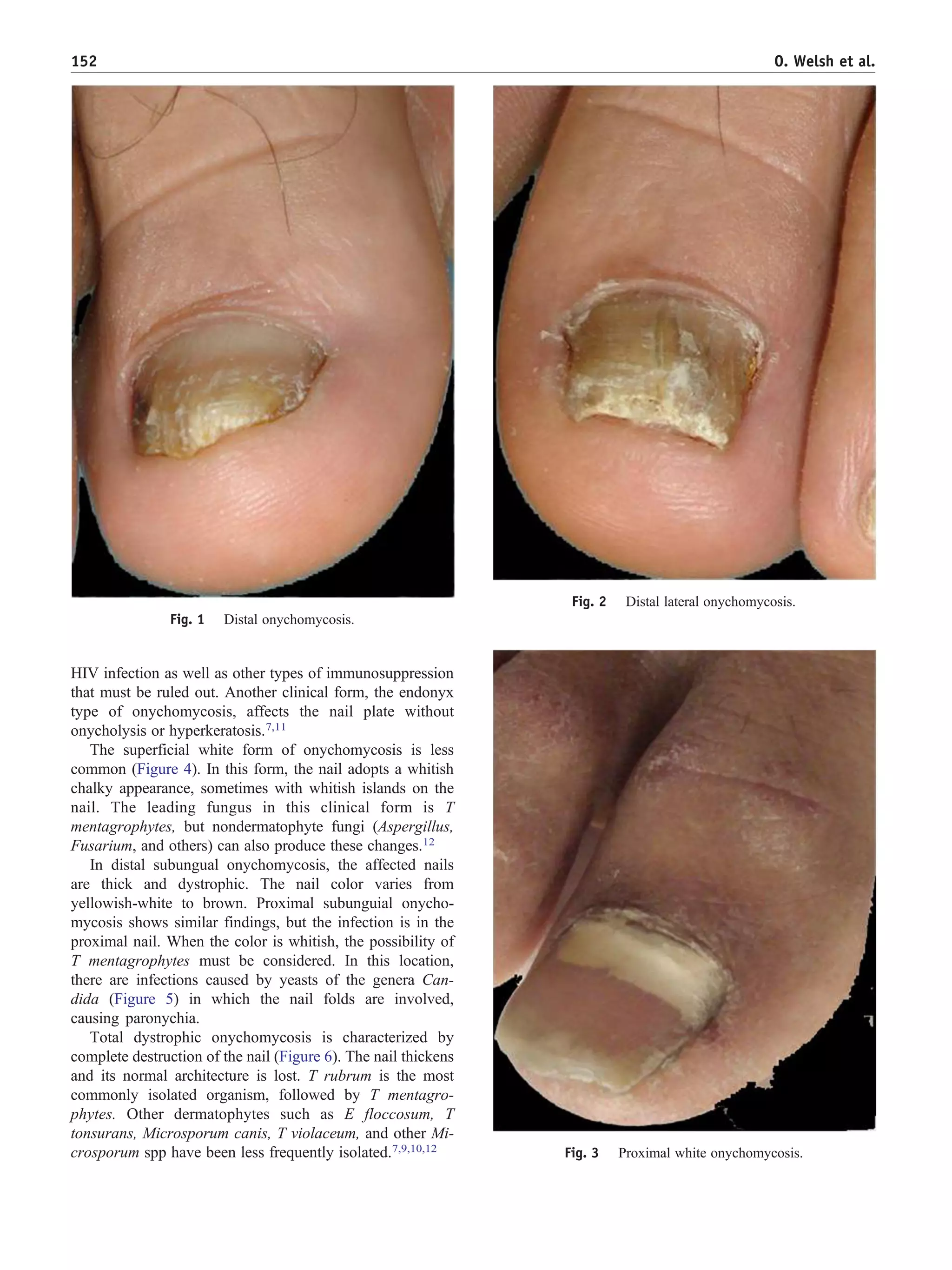

This document discusses onychomycosis, a common nail fungus. It begins by defining onychomycosis and describing the most common causes as dermatophytes (fungi that infect skin, hair, and nails) such as Trichophyton rubrum, yeasts such as Candida species, and other molds. It then discusses the different clinical presentations of onychomycosis and outlines the primary diagnostic methods of direct microscopic examination, culture, and histopathology to confirm the presence of fungi in the nail. The document focuses on proper sampling techniques for these diagnostic tests and stresses the importance of culture to identify the infecting species and determine appropriate treatment.

![References

1. Elewski B, Charif M. Prevalence of onychomycosis in patients

attending a dermatology clinic in northeastern Ohio for other

conditions. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:1172-3.

2. Elewski B. Onychomycosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management.

Clin Microbiol Rev 1998;11:415-29.

3. Faergemann J, Correia O, Nowicki R, Ro BI. Genetic predisposition—

understanding underlying mechanisms of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad

Dermatol Venereol 2005;19(Suppl 1):17-9.

4. Heikkilä H, Stubb S. The prevalence of onychomycosis in Finland. Br J

Dermatol 1995;133:699-703.

5. Lateur N, Mortaki A, André J. Two hundred ninety-six cases of

onychomycosis in children and teenagers: a 10-year laboratory survey.

Pediatr Dermatol 2003;20:385-8.

6. Effendy I, Lecha M, Feuilhade de Chauvin M, Di Chiacchio N, Baran

R. European Onychomycosis Observatory. Epidemiology and clinical

classification of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;

19(Suppl 1):8-12.

7. Hay R. Literature review. Onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol

Venereol 2005;19(Suppl 1):1-7.

8. Welsh O, Welsh E, Ocampo-Candiani J, Gomez M, Vera-Cabrera L.

Dermatophytoses in Monterrey, México. Mycoses 2006;49:119-23.

9. Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of

dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia 2008 2008;166:335-52.

10. Kaur R, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Onychomycosis—epidemiology,

diagnosis and management. Indian J Med Microbiol 2008;26:108-16.

11. Gupta AK, Ryder JE, Summerbell RC. Onychomycosis: classification

and diagnosis. J Drugs Dermatol 2004;3:51-6.

12. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Lorenzi S. Onychomycosis caused by

nondermatophytic molds: clinical features and response to treatment

of 59 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;42:217-24.

13. Gupta AK, Ricci MJ. Diagnosing onychomycosis. Dermatol Clin 2006;

24:365-9.

14. Arca E, Saracli MA, Akar A, Yildiran ST, Kurumlu Z, Gur AR.

Polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Eur J

Dermatol 2004;14:52-5.

15. Weinberg JM, Koestenblatt EK, Tutrone WD, Tishler HR, Najarian L.

Comparison of diagnostic methods in the evaluation of onychomycosis.

J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:193-7.

16. Shemer A, Davidovici B, Grunwald MH, Trau H, Amichai B.

Comparative study of nail sampling techniques in onychomycosis. J

Dermatolog Treat 2009;36:410-4.

17. Shemer A, Davidovici B, Grunwald MH, Trau H, Amichai B. New

criteria for the laboratory diagnosis of nondermatophyte moulds in

onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol 2008-2009;160:37-9.

18. Piérard GE, Quatresooz P, Arrese JE. Spotlight on nail histomycology.

Dermatol Clin 2006;24:371-4.

19. Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Garlowska E, Kulig M, Baran E.

Onychomycosis Epidemiology Study Group. Factors influencing

coexistence of toenail onychomycosis with tinea pedis and other

dermatomycoses: a survey of 2761 patients. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:

1279-84.

20. Cathcart S, Cantrell W, Elewski B. Onychomycosis and diabetes. J Eur

Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:1119-22.

21. Baran R, Hay RJ, Garduno J. Review of antifungal therapy and the

severity index for assessing onychomycosis: part I. J Dermatolog Treat

2008;19:72-81.

22. Baran R, Hay RJ, Garduno J. Review of antifungal therapy, part II:

treatment rationale, including specific patient populations. J Dermato-

log Treat 2008;19:168-75.

23. Kumar S, Kimball AB. New antifungal therapies for the treatment of

onychomycosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2009;18:727-34.

24. Nair AB, Kim HD, Chakraborty B, et al. Ungual and trans-ungual

iontophoretic delivery of terbinafine for the treatment of onychomy-

cosis. J Pharm Sci 2009;98:4130-40.

25. Baran R, Kaoukhov A. Topical antifungal drugs for the treatment of

onychomycosis: an overview of current strategies for monotherapy

and combination therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005;19:

21-9.

26. Watanabe D, Kawamura C, Masuda Y, Akita Y, Tamada Y, Matsumoto

Y. Successful treatment of toenail onychomycosis with photodynamic

therapy. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:19-21.

27. Piraccini BM, Rech G, Tosti A. Photodynamic therapy of onycho-

mycosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;

59(5 Suppl):S75-76.

28. Huang PH, Paller AS. Itraconazole pulse therapy for dermatophyte

onychomycosis in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:

614-8.

29. Gupta AK, Cooper EA, Montero-Gei F. The use of fluconazole to treat

superficial fungal infections in children. Dermatol Clin 2003;21:

537-42.

30. Sethi A, Antaya R. Systemic antifungal therapy for cutaneous infections

in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006;25:643-4.

31. Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophy-

tosis. Mycopathologia 2008;166:353-67.

32. Gupta AK, Cooper EA, Ginter G. Efficacy and safety of itraconazole

use in children. Dermatol Clin 2003;21:521-35.

33. Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Lorizzo M. Management of onychomycosis in

children. Dermatol Clin 2003;21:507-9 [vii].

34. Bonifaz A, Ibarra G. Onychomycosis in children: treatment with

bifonazole-urea. Pediatr Dermatol 2000;17:310-4.

35. Suarez S, Friedlander SF. Antifungal therapy in children: an update.

Pediatr Ann 1998;27:177-84.

36. Gupta AK, Ryder JE, Lynch LE, Tavakkol A. The use of terbinafine in

the treatment of onychomycosis in adults and special populations: a

review of the evidence. J Drugs Dermatol 2005:302-8.

37. Pasqualotto AC, Denning DW. New and emerging treatments for

fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;61(Suppl 1):

i19-i30.

38. Girmenia C. New generation azole antifungals in clinical investigation.

Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2009;18:1279-95.

39. Gonzalez GM, Elizondo M, Ayala J. Trends in species distribution

and susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida collected in

Monterrey, Mexico, to seven antifungal agents: results of a 3-year

(2004 to 2007) surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:

2902-5.

40. Gupta AK, Leonardi C, Stoltz RR, Pierce PF, Conetta B. A phase I/II

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study

evaluating the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of ravuconazole

in the treatment of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

2005;19:437-43.

41. Geria AN, Scheinfeld NS. Pramiconazole, a triazole compound for the

treatment of fungal infections. IDrugs 2008;11:661-70.

42. Lecha M. Amorolfine and itraconazole combination for severe toenail

onychomycosis; results of an open randomized trial in Spain. Br J

Dermatol 2001;145(Suppl 60):21-6.

43. Sergeev Y, Sergeev A. Pulsed combination therapy: a new option for

onychomycosis. Mycoses 2001;44(Suppl 1):68-9.

44. Gupta AK, Lynde CW, Konnikov N. Single-blind, randomized,

prospective study of sequential itraconazole and terbinafine pulse

compared with terbinafine pulse for the treatment of toenail

onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:485-91.

45. Polak A. Preclinical data and mode of action of amorolfine.

Dermatology 1992;184(Suppl 1):3-7.

46. Gupta AK, Schouten JR, Lynch LE. Ciclopirox nail lacquer 8% for the

treatment of onychomycosis: a Canadian perspective. Skin Therapy Lett

2005;10:1-3.

47. Barak O, Loo DS. A novel antifungal for the topical treatment of

onychomycosis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2007;8:662-8.

48. Scher RK, Tavakkol A, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Onychomycosis:

diagnosis and definition of cure. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:

939-44.

159Onychomycosis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/onychomycosispiis0738081x0900248x-150417201212-conversion-gate02/75/Onicomicosis-9-2048.jpg)