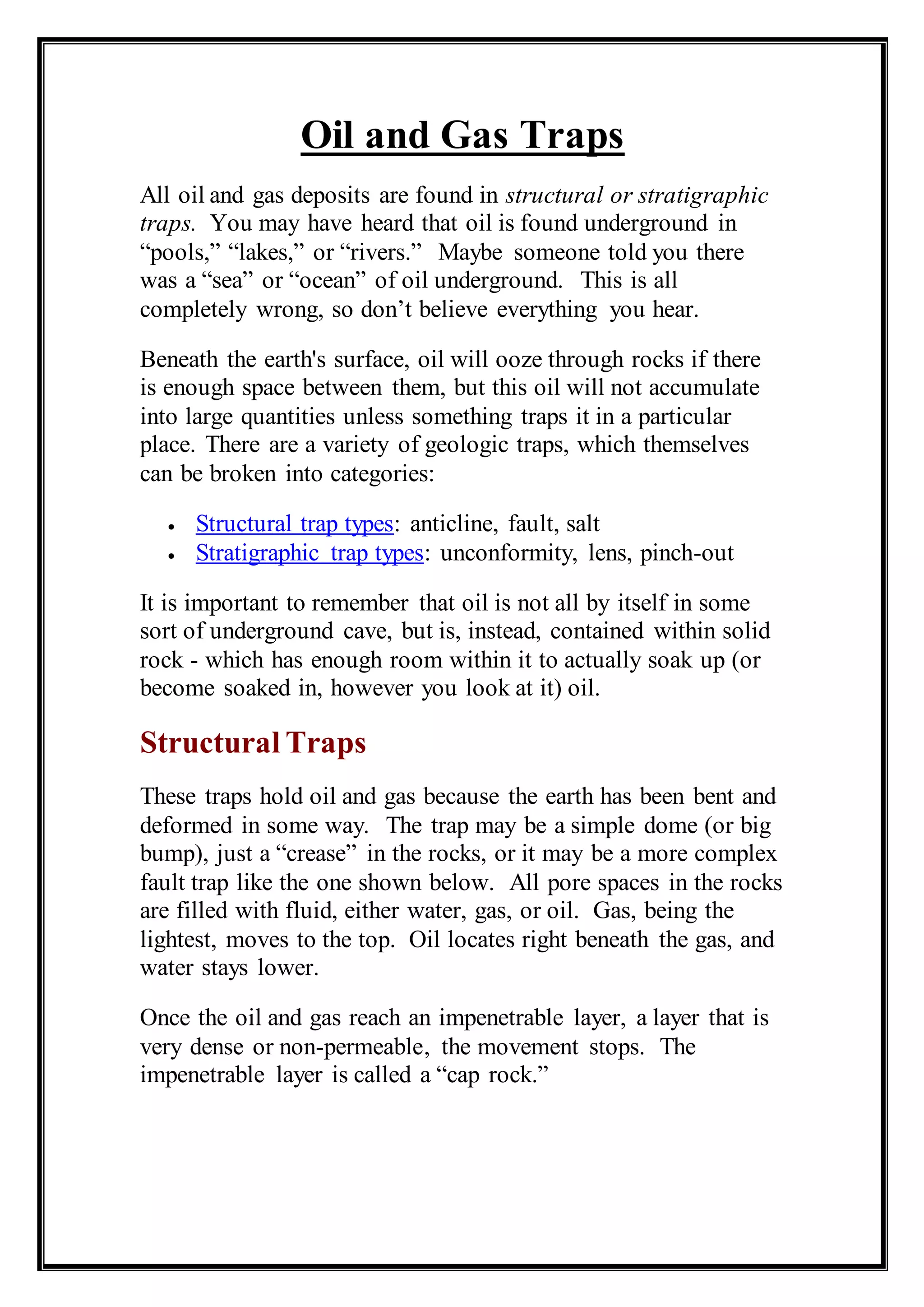

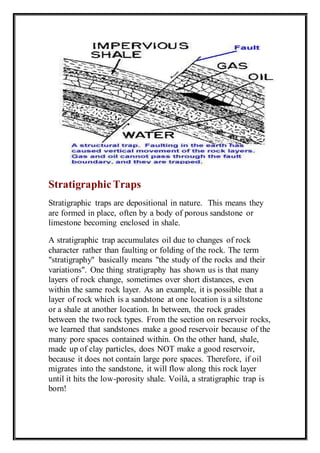

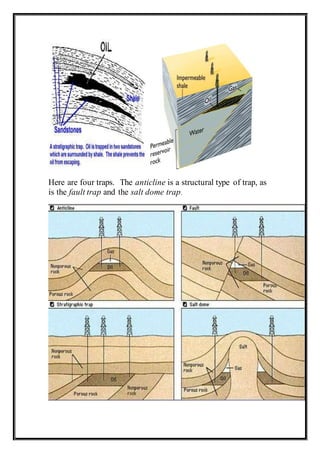

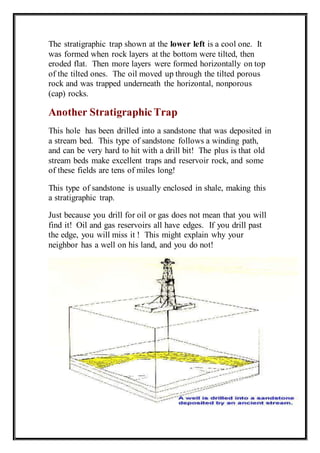

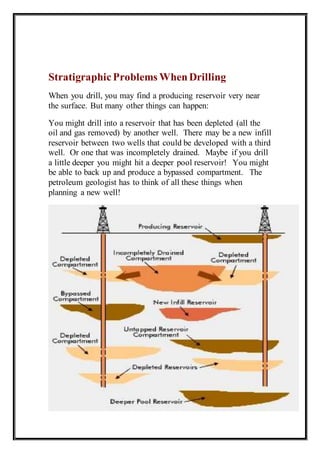

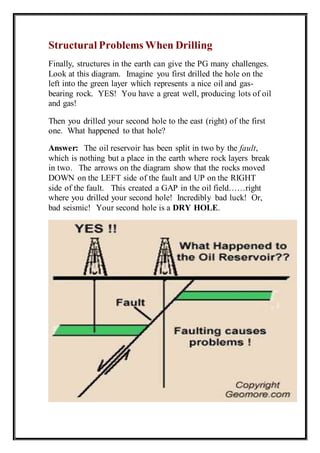

There are two main types of traps that can contain oil and gas deposits underground: structural traps and stratigraphic traps. Structural traps form when rock layers are bent or broken through geologic processes like folding or faulting. Stratigraphic traps form when permeable rock layers, like sandstone, become surrounded by impermeable layers, like shale, that trap the oil and gas inside. It is important for identifying potential oil and gas reservoirs that petroleum geologists understand the complex variations in rock layers and how different rock types can trap hydrocarbon deposits in different ways either structurally or stratigraphically.