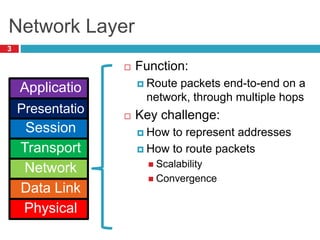

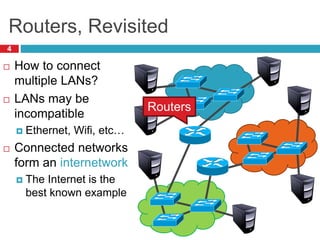

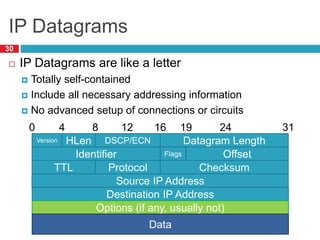

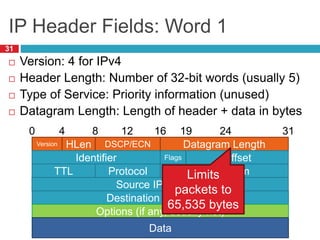

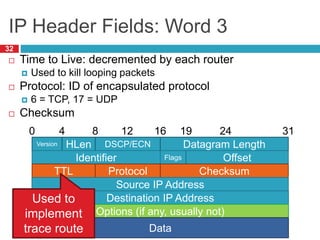

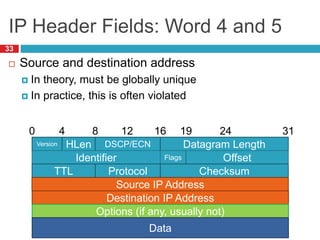

The document discusses network layer concepts including addressing, routing, and fragmentation in computer networks. It covers:

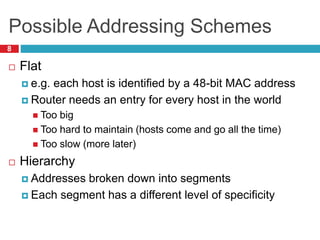

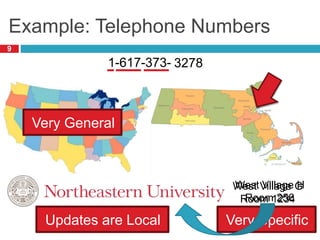

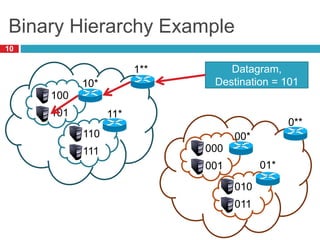

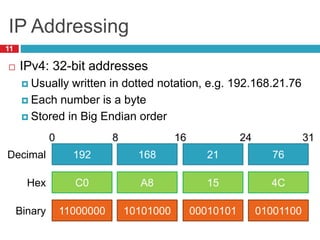

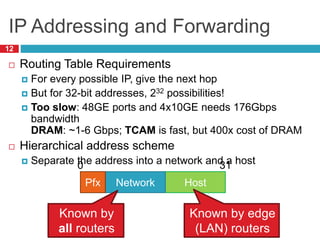

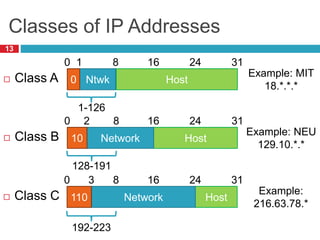

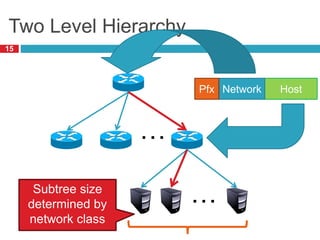

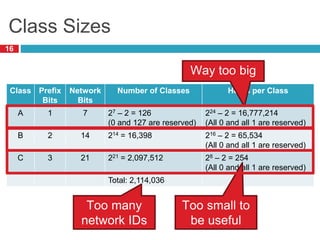

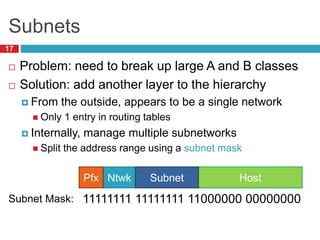

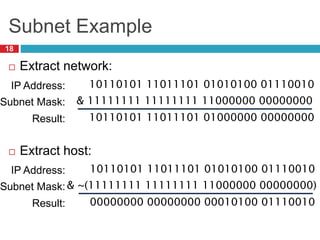

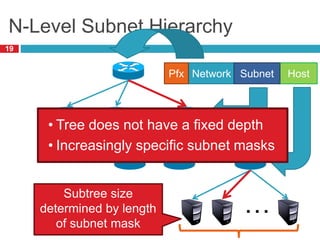

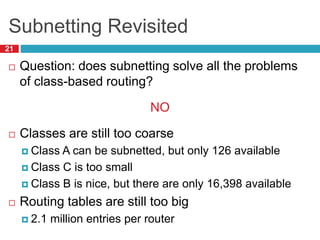

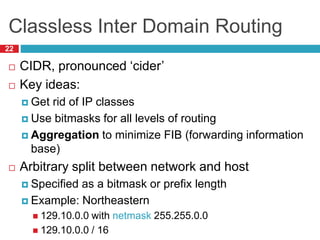

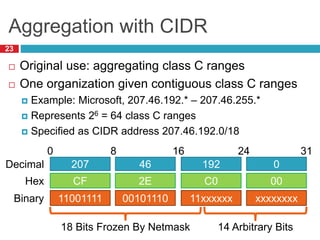

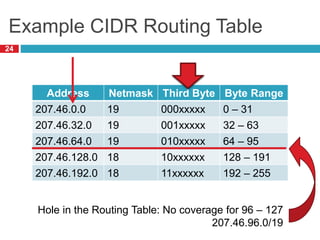

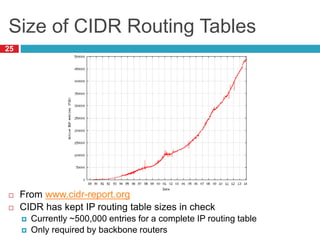

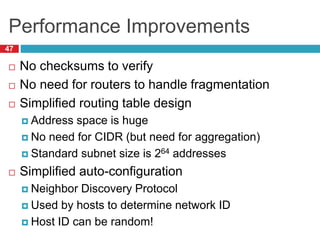

1) Hierarchical addressing schemes like CIDR are used to allow routing scalability through aggregation. This involves dividing IP addresses into a network and host portion.

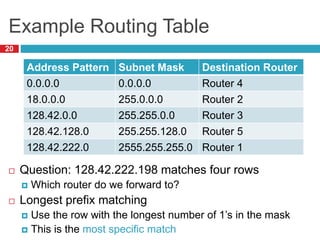

2) Routers use longest prefix matching on IP addresses and routing tables to determine how to forward packets between networks.

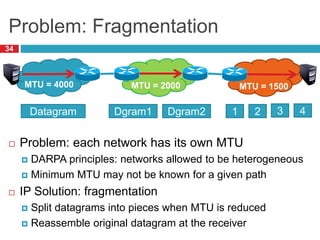

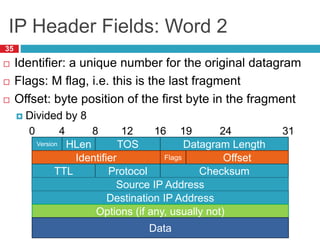

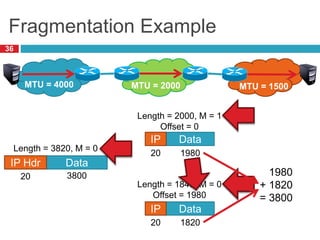

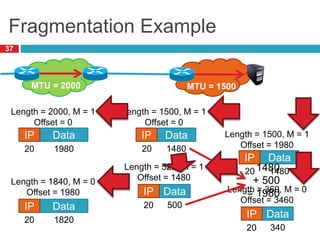

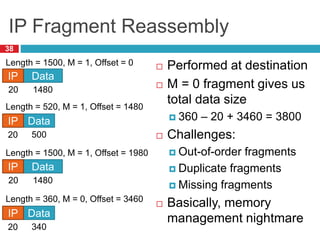

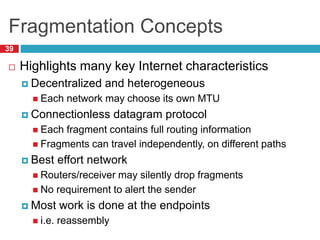

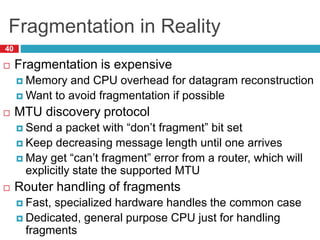

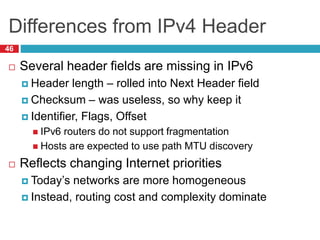

3) Fragmentation allows transmission of packets across heterogeneous networks with different MTUs by splitting packets into pieces that are reassembled at the destination.