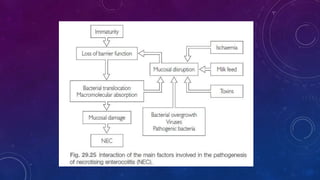

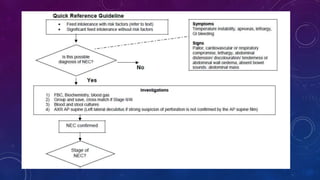

This document provides an overview of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), including its epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical features, management, outcomes, prevention and areas for further research. Some key points:

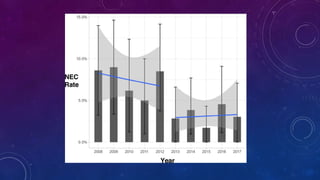

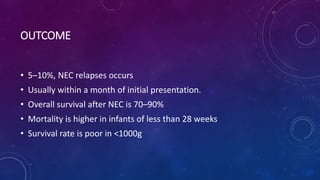

- NEC most commonly affects very preterm infants, with a mortality rate around 13% that increases with lower birth weight.

- Risk factors include prematurity, hypoxia, poor intestinal integrity, bacterial colonization and enteral feeding.

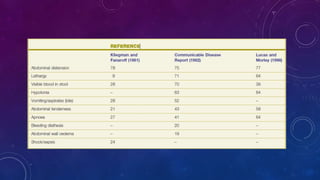

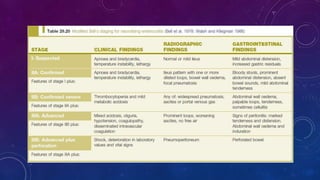

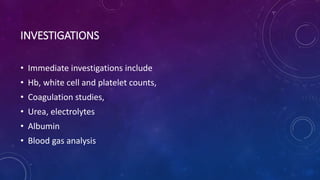

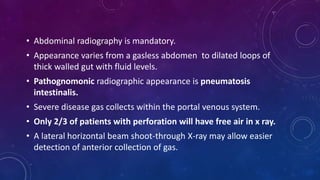

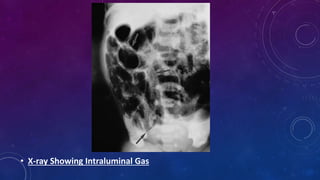

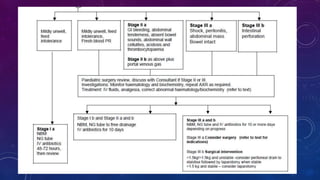

- Clinically it presents with abdominal distension, bloody stools and vomiting. Diagnosis is confirmed via x-ray showing pneumatosis or free air.

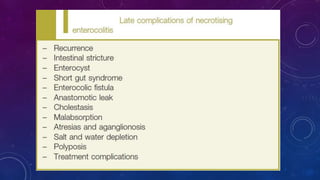

- Management involves stopping feeds, antibiotics, surgery for complications like perforation.