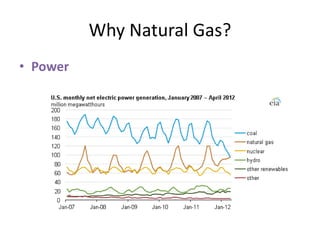

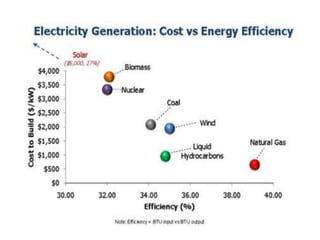

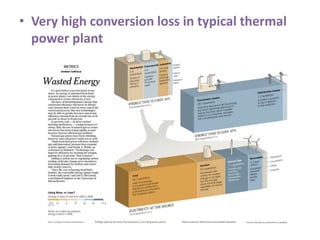

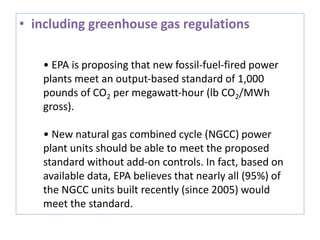

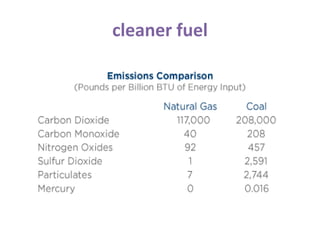

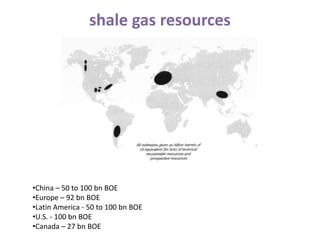

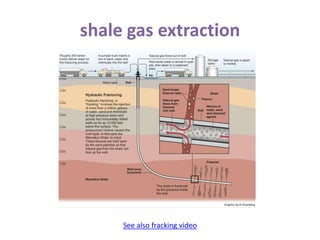

The document discusses the opportunities and issues around natural gas. It notes that natural gas power plants are more efficient than coal plants and produce fewer emissions. However, shale gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing poses various environmental and health risks, including potential groundwater contamination and increased seismic activity. The document outlines recommendations from the International Energy Agency to promote responsible shale gas development, including measuring impacts, engaging communities, minimizing water usage, eliminating emissions, and ensuring robust regulation.