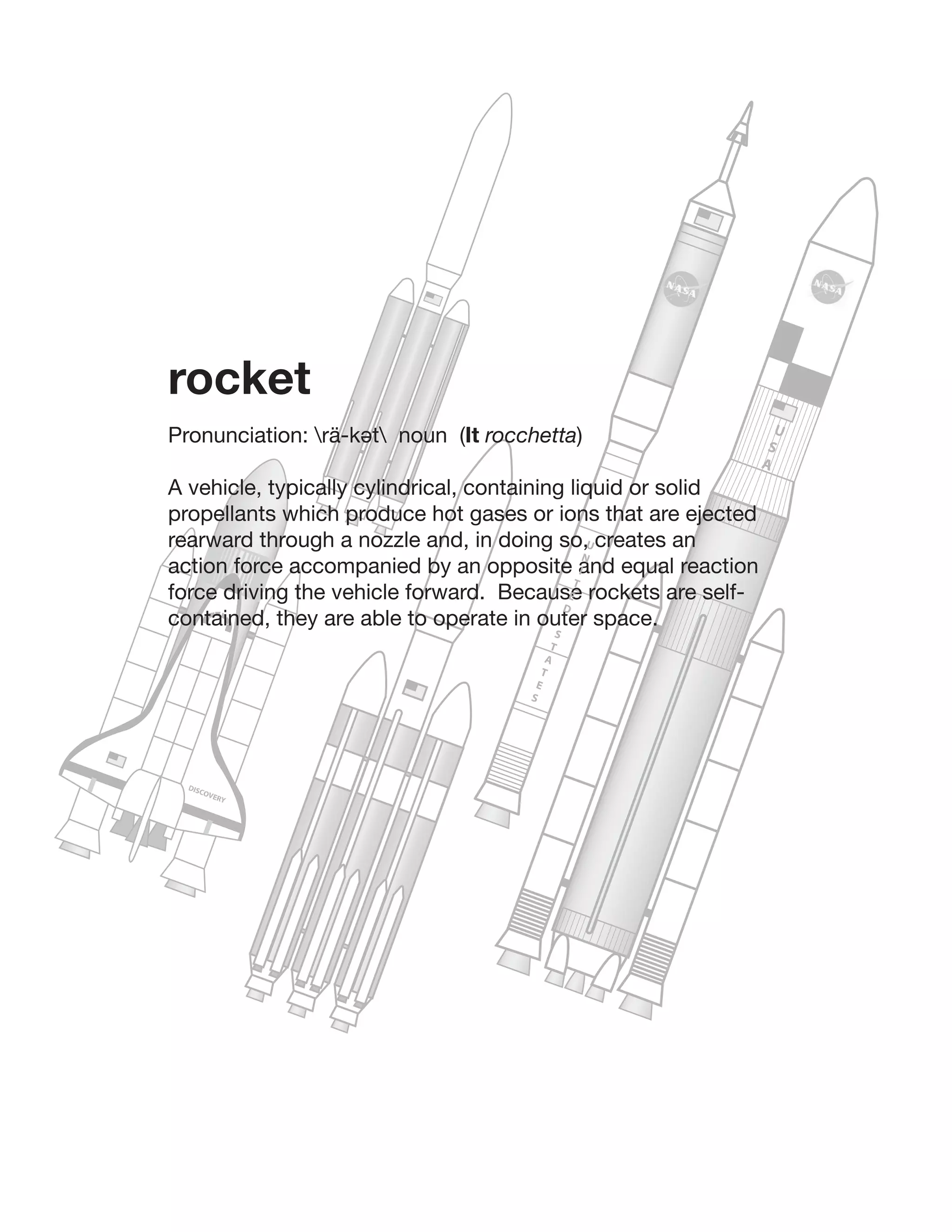

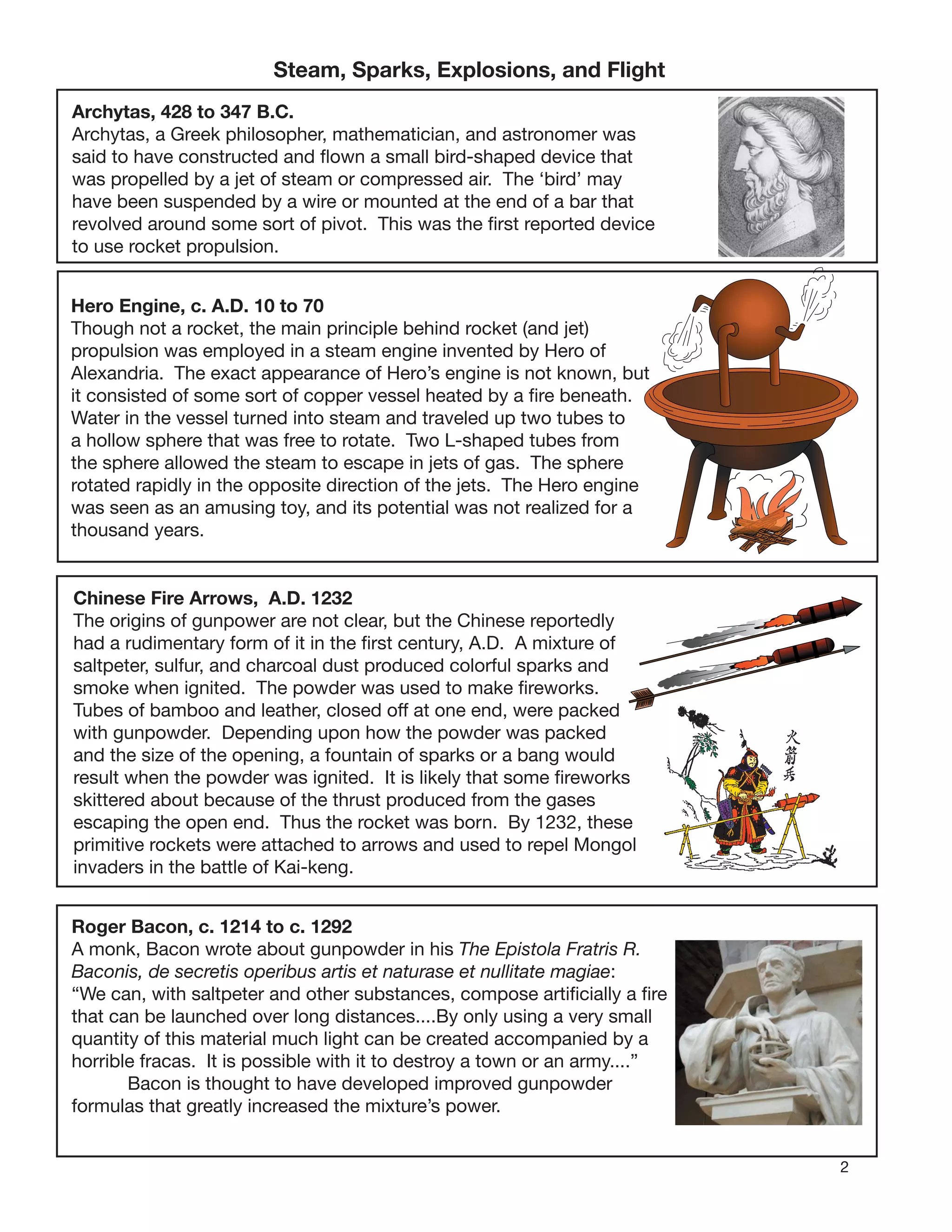

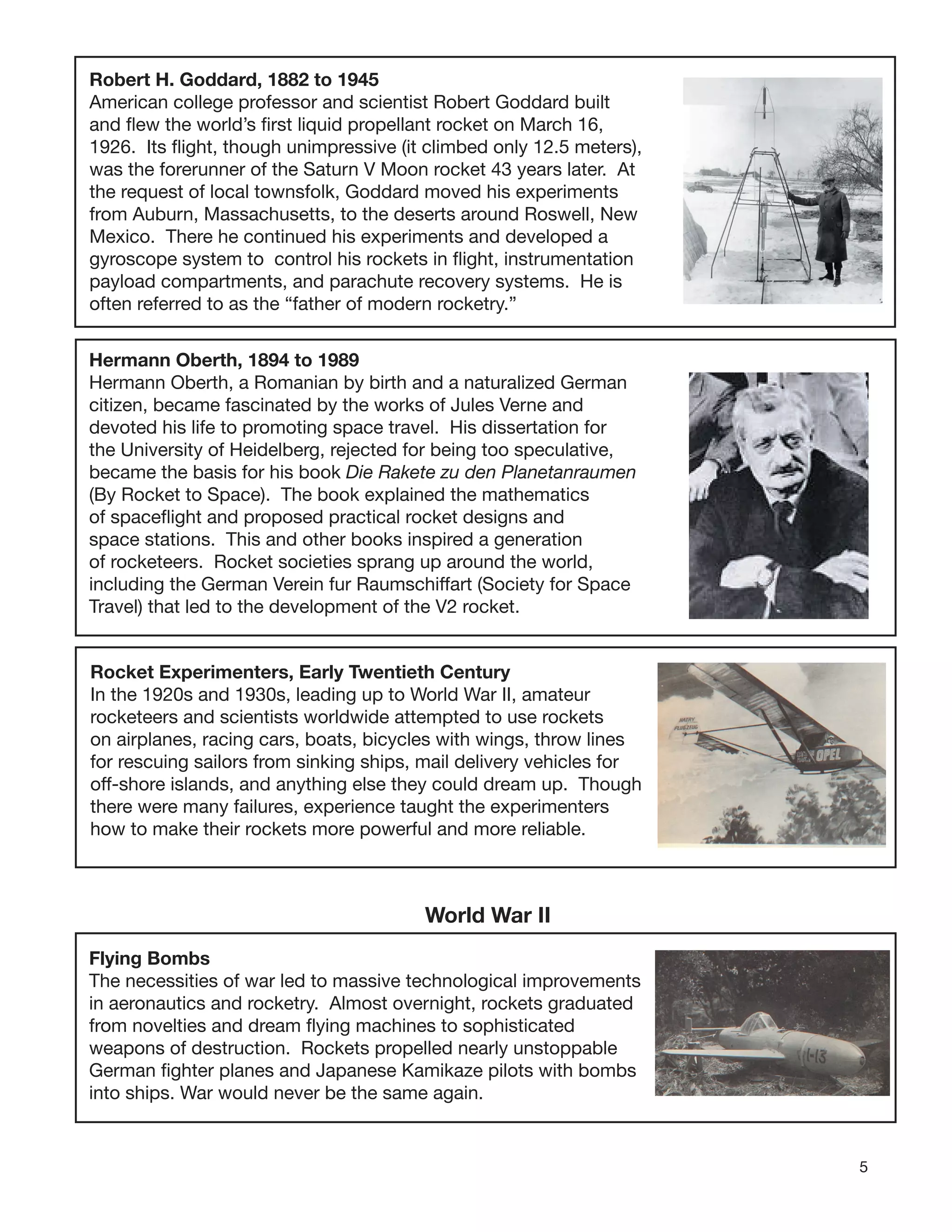

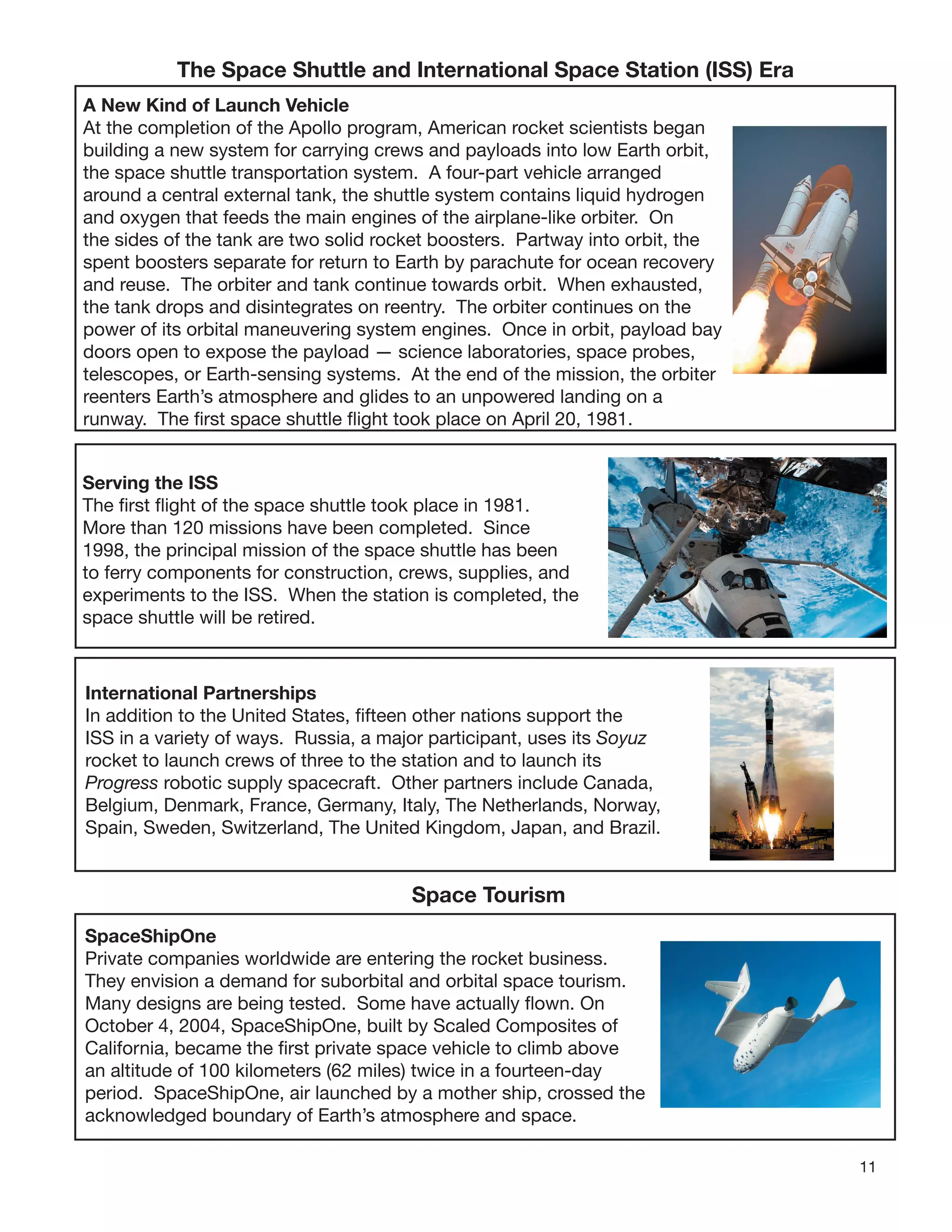

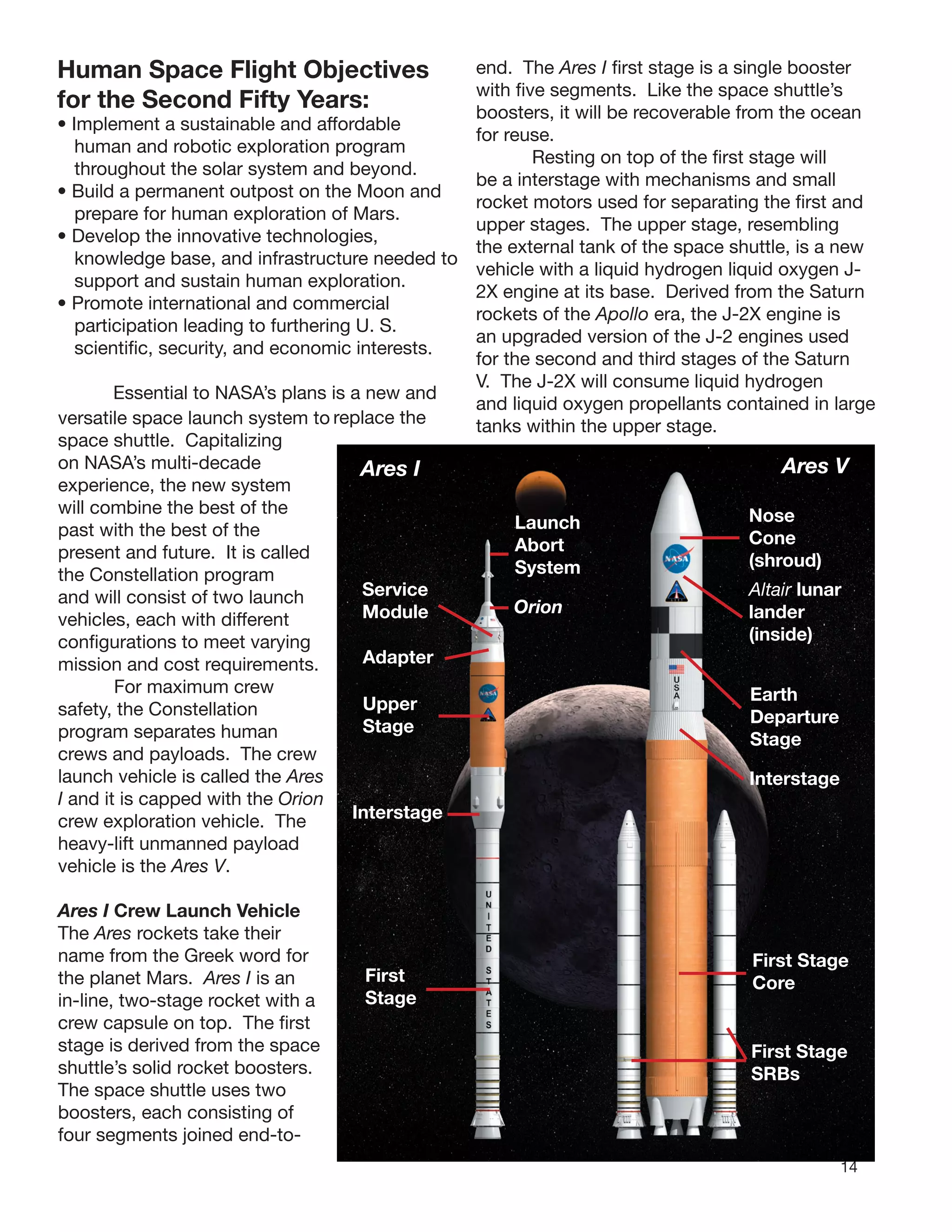

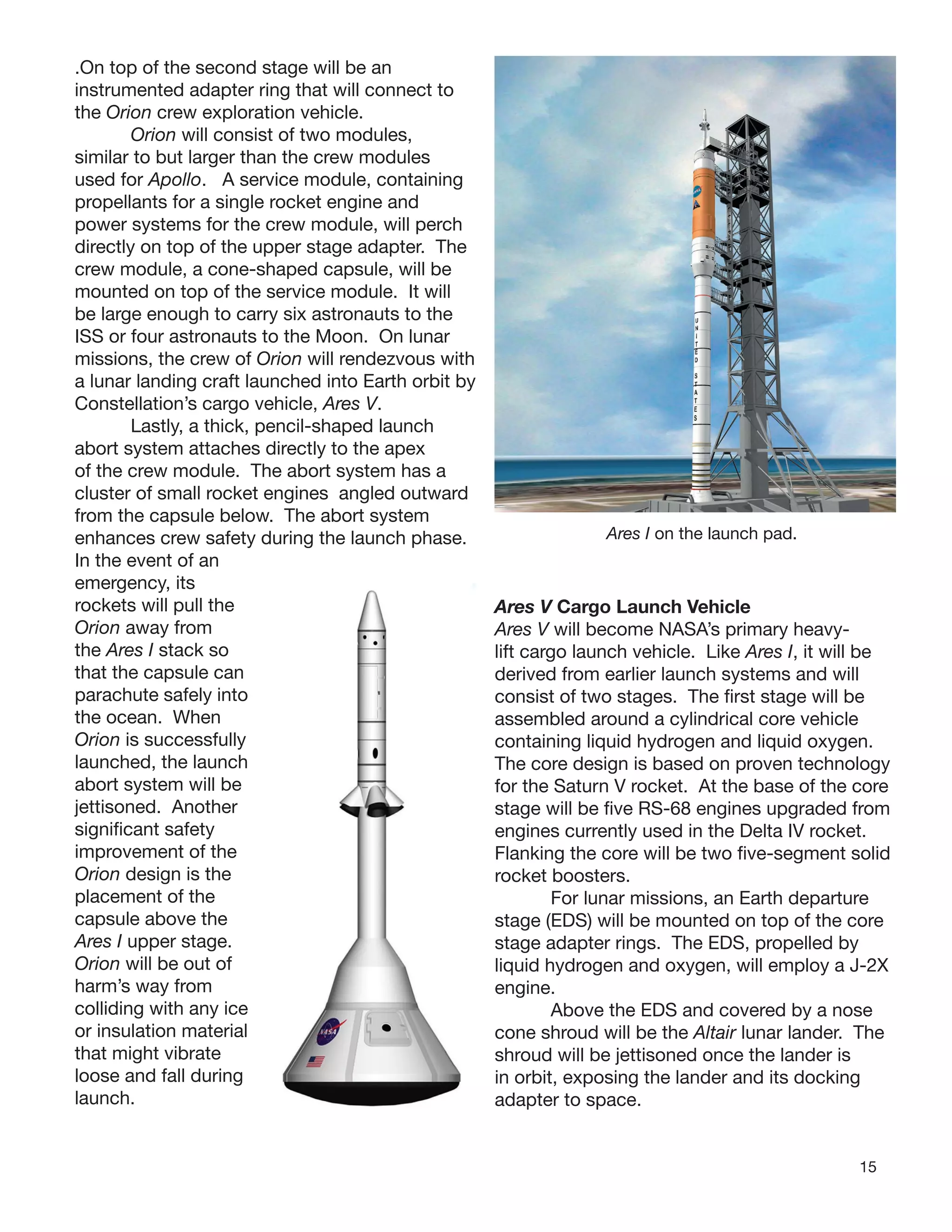

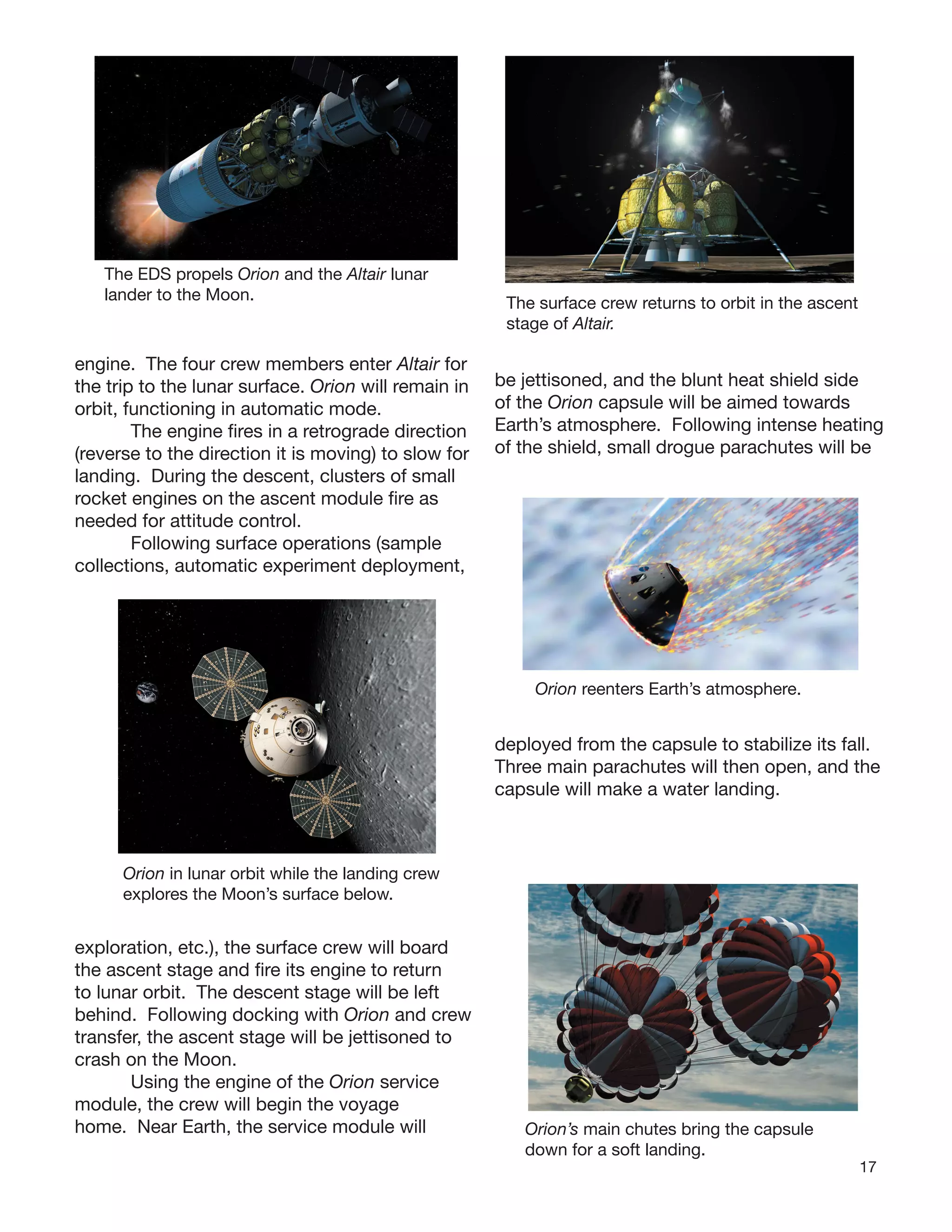

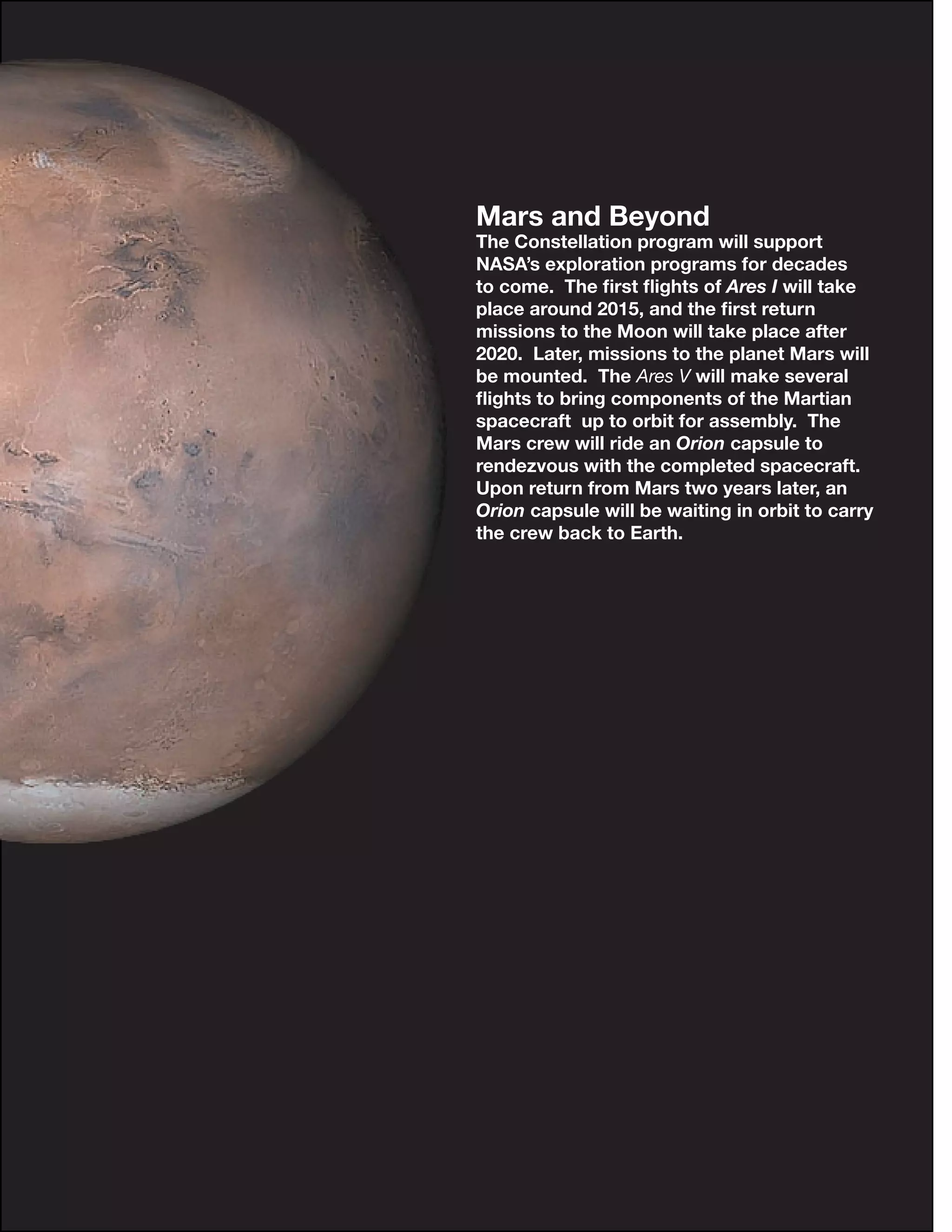

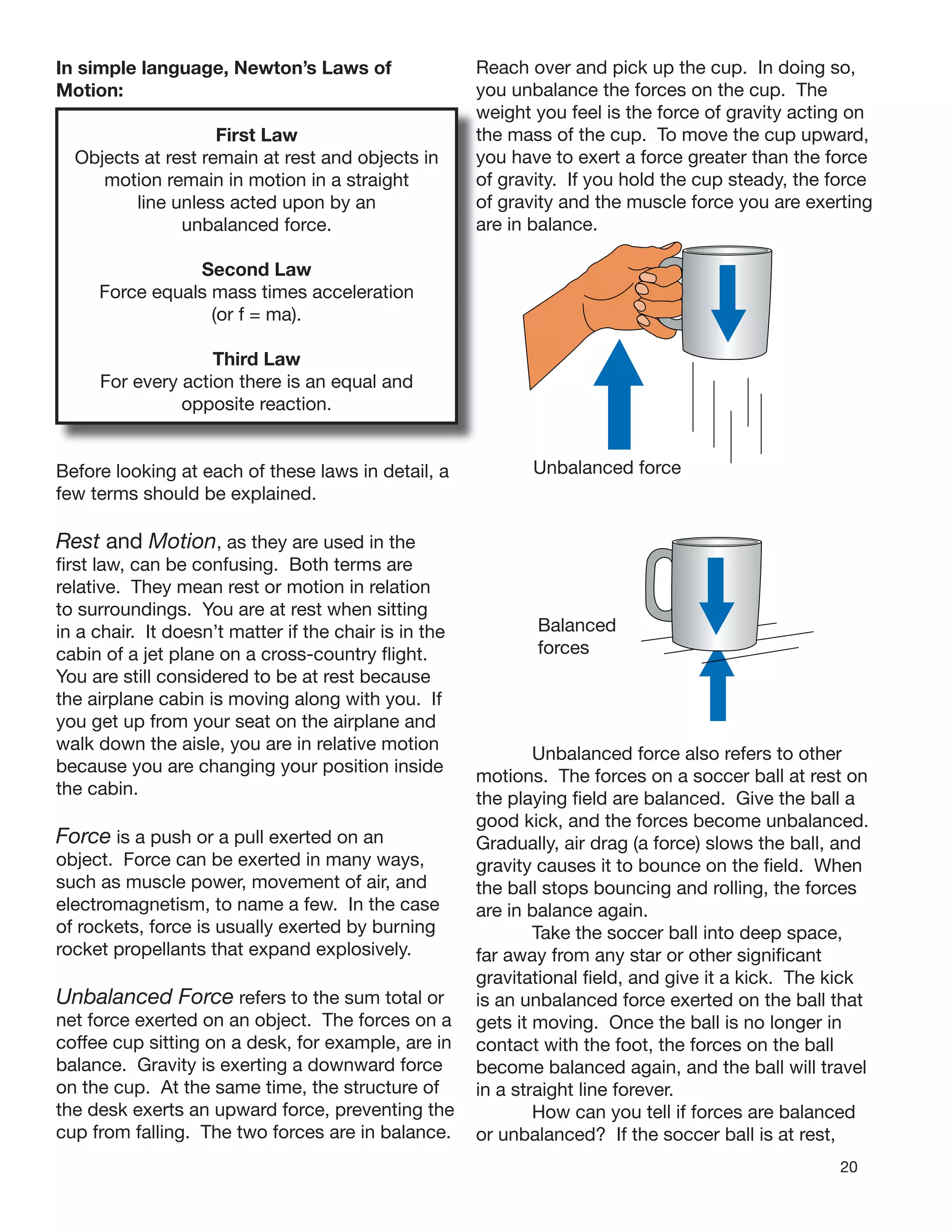

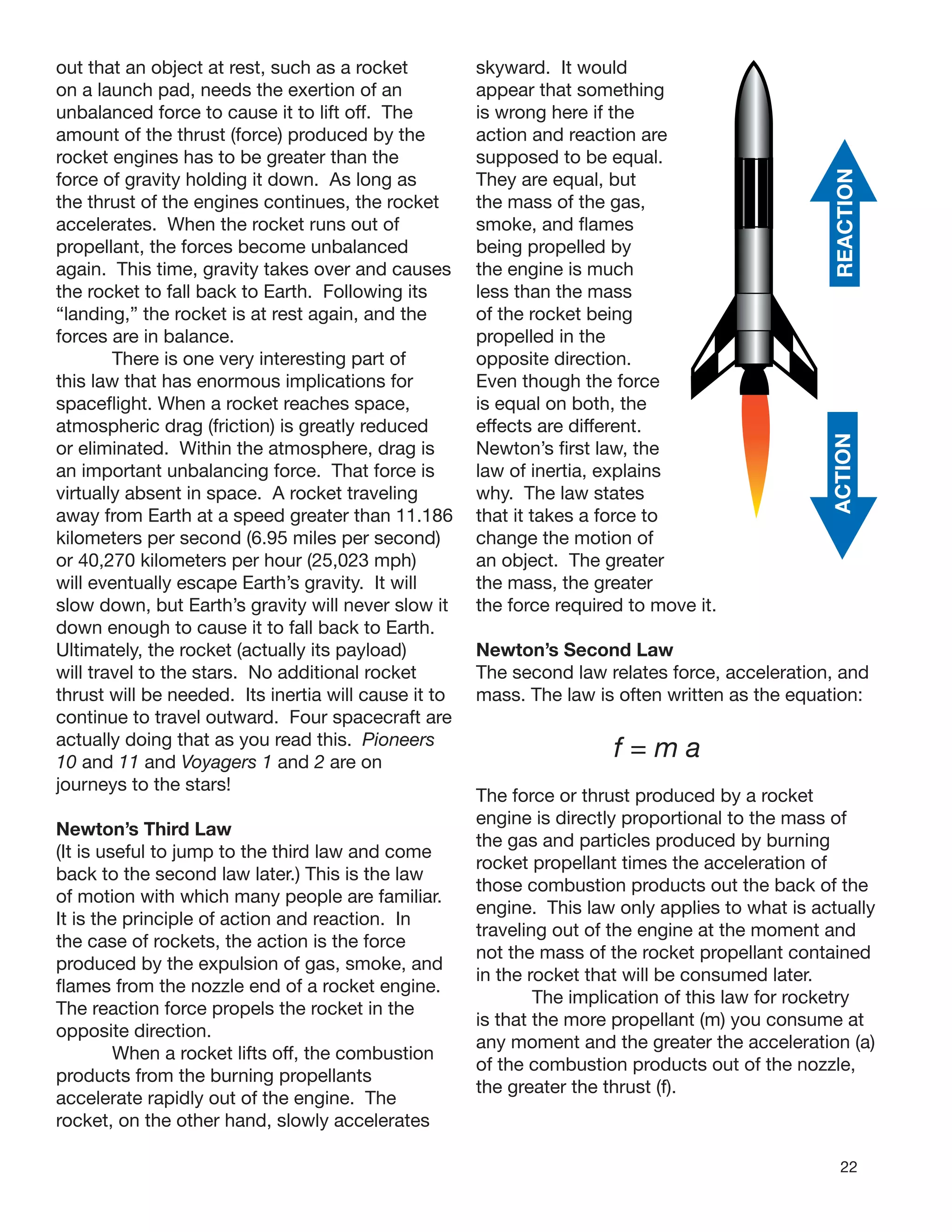

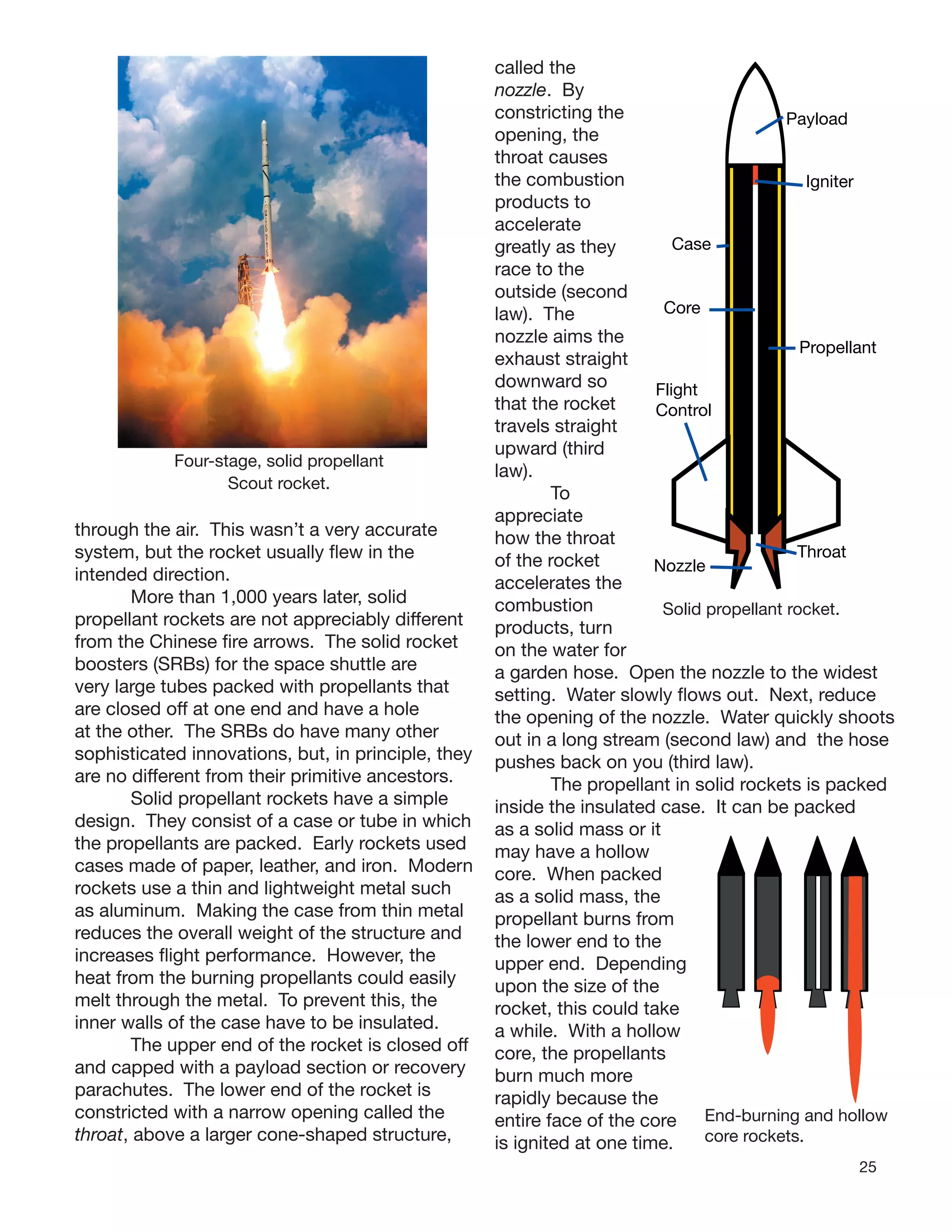

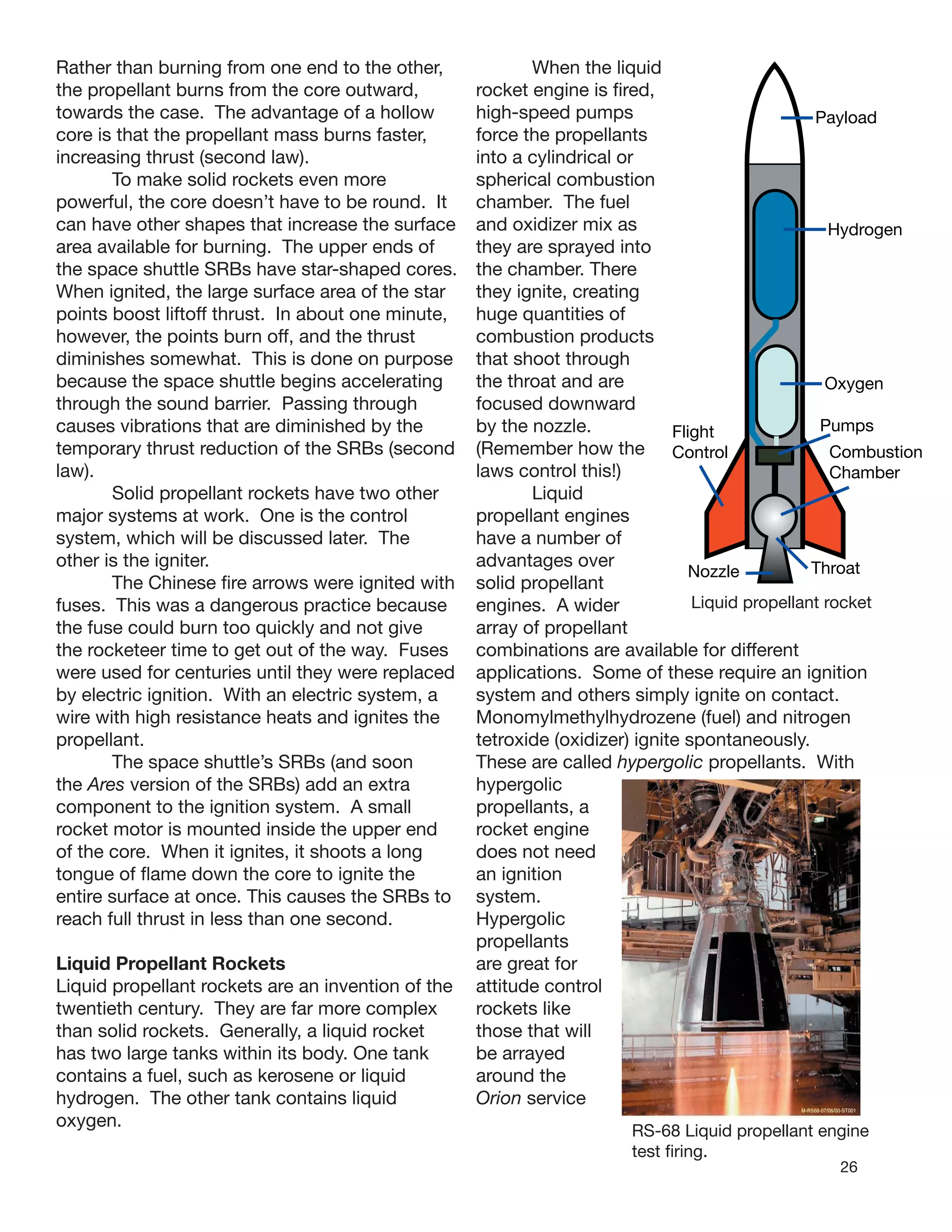

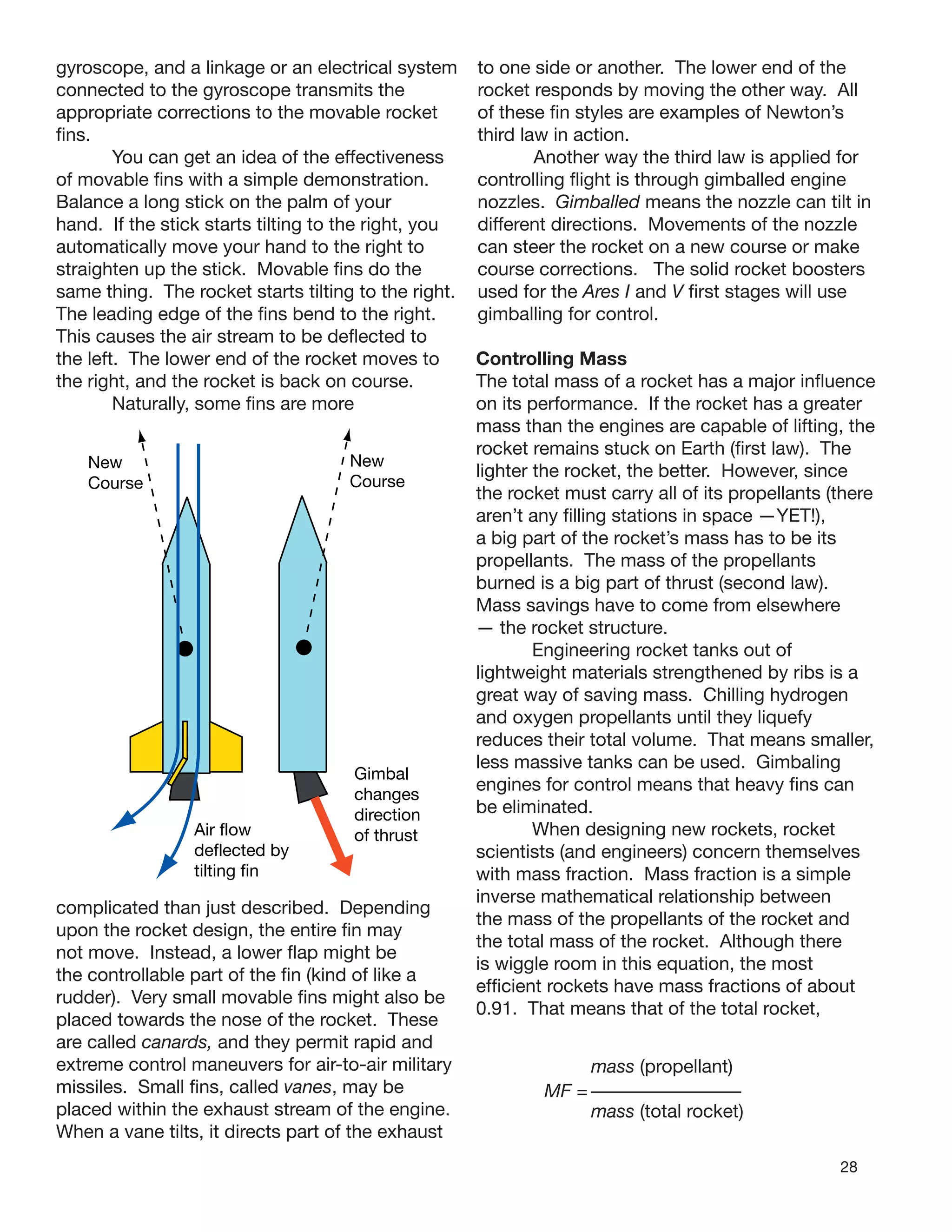

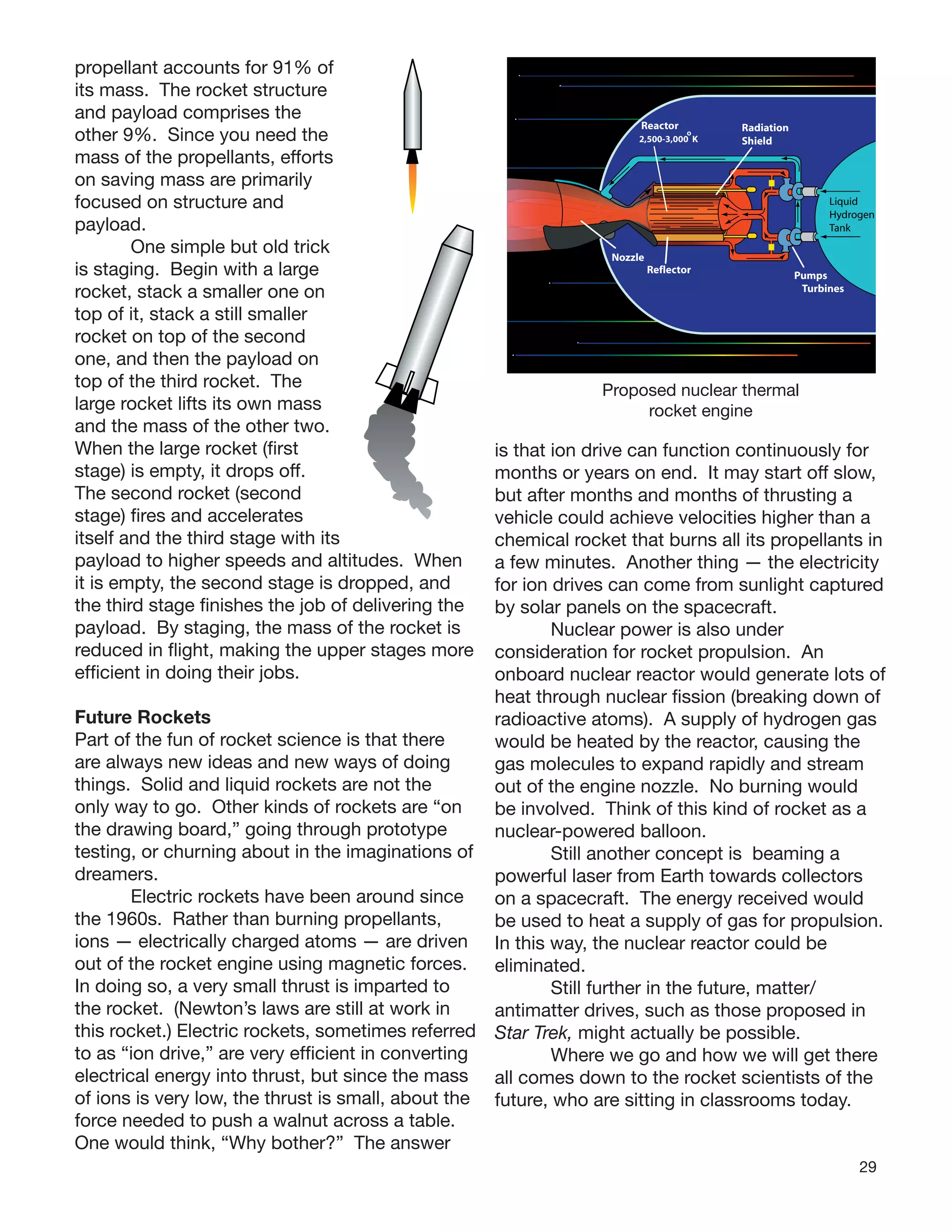

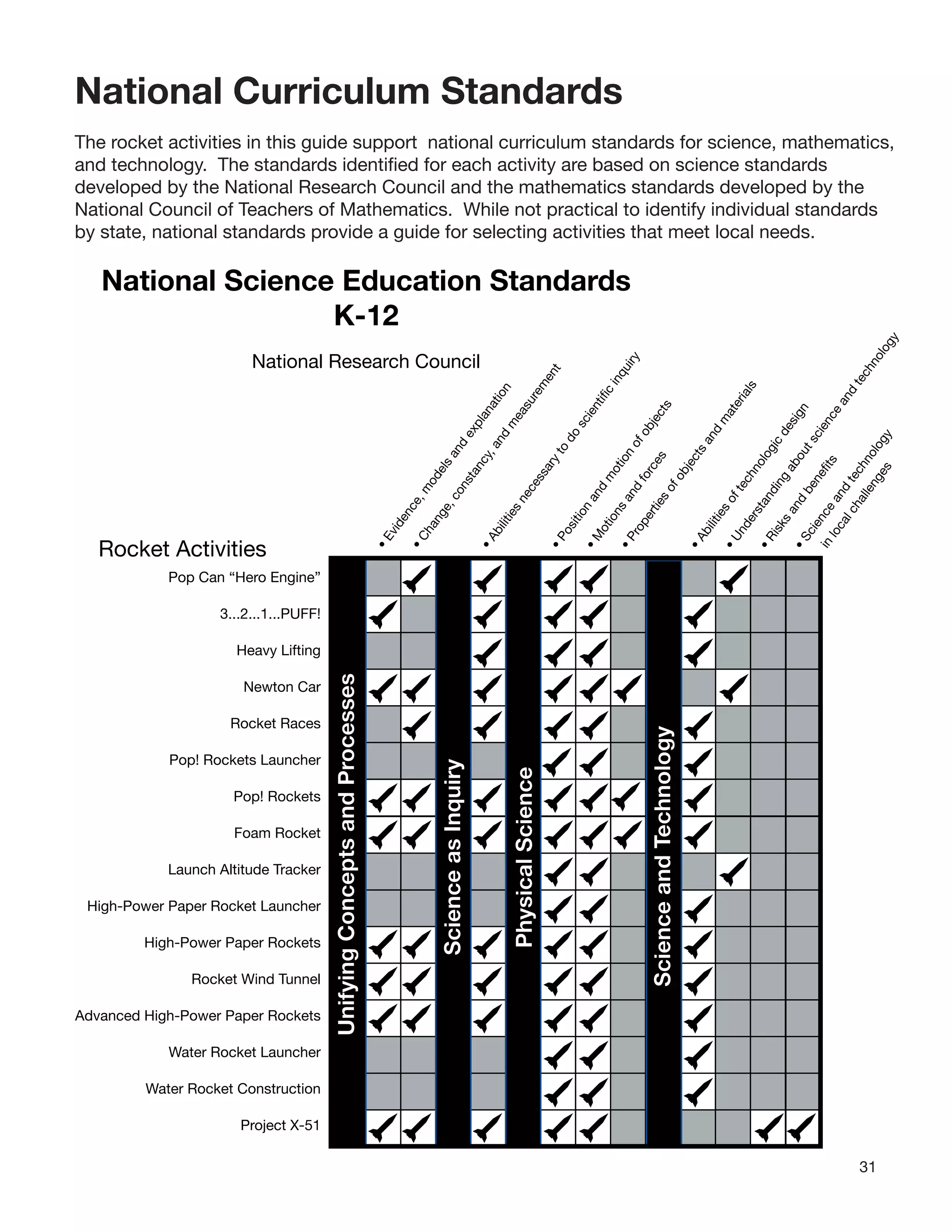

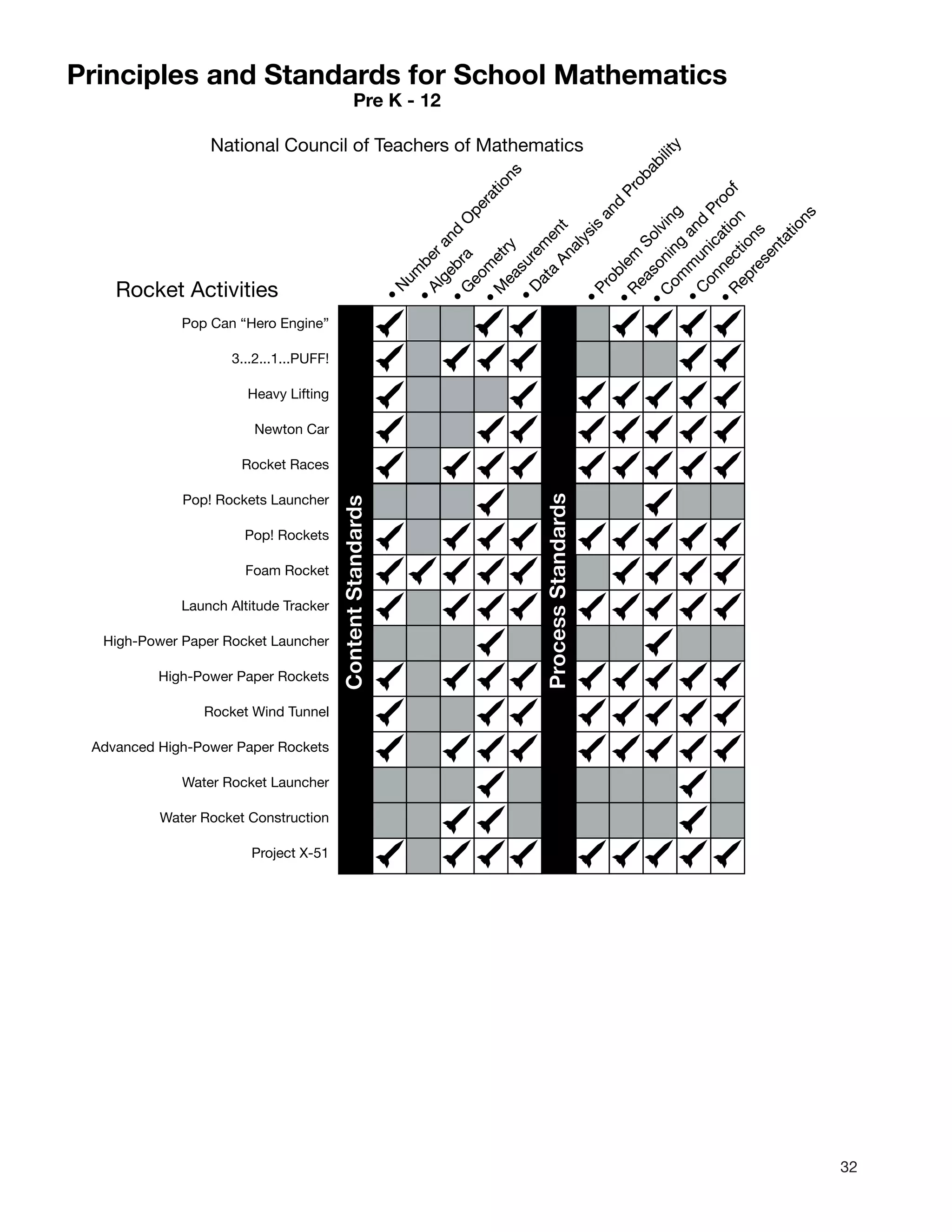

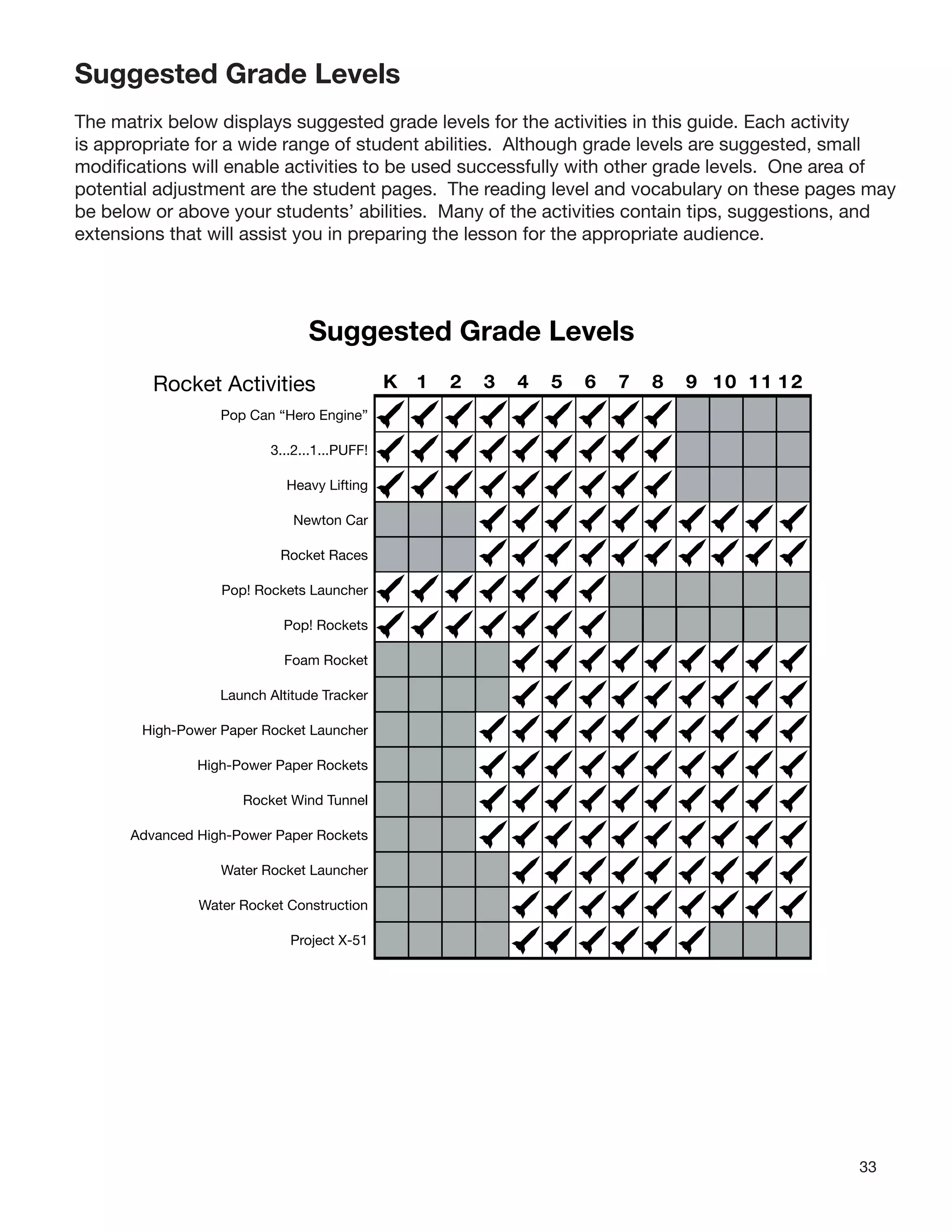

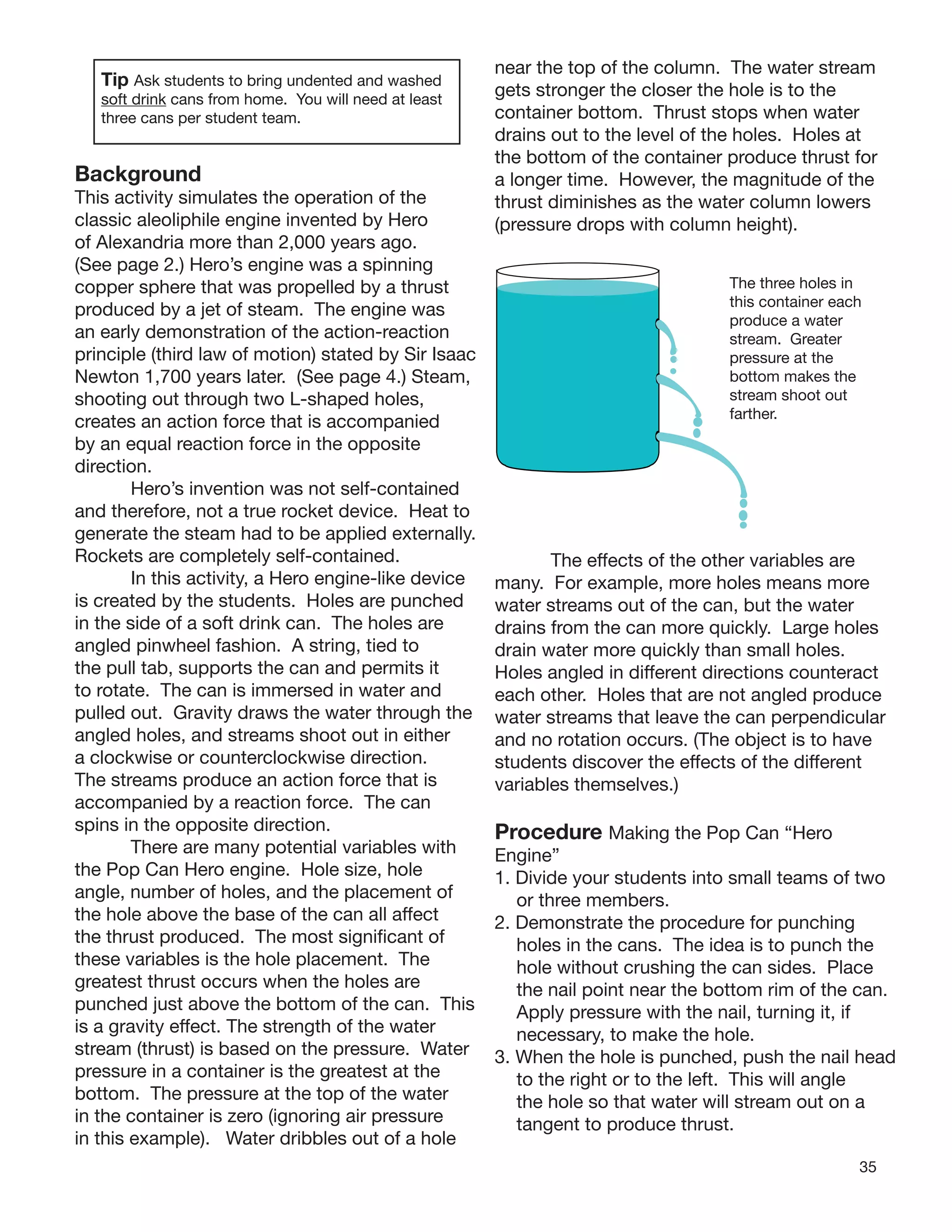

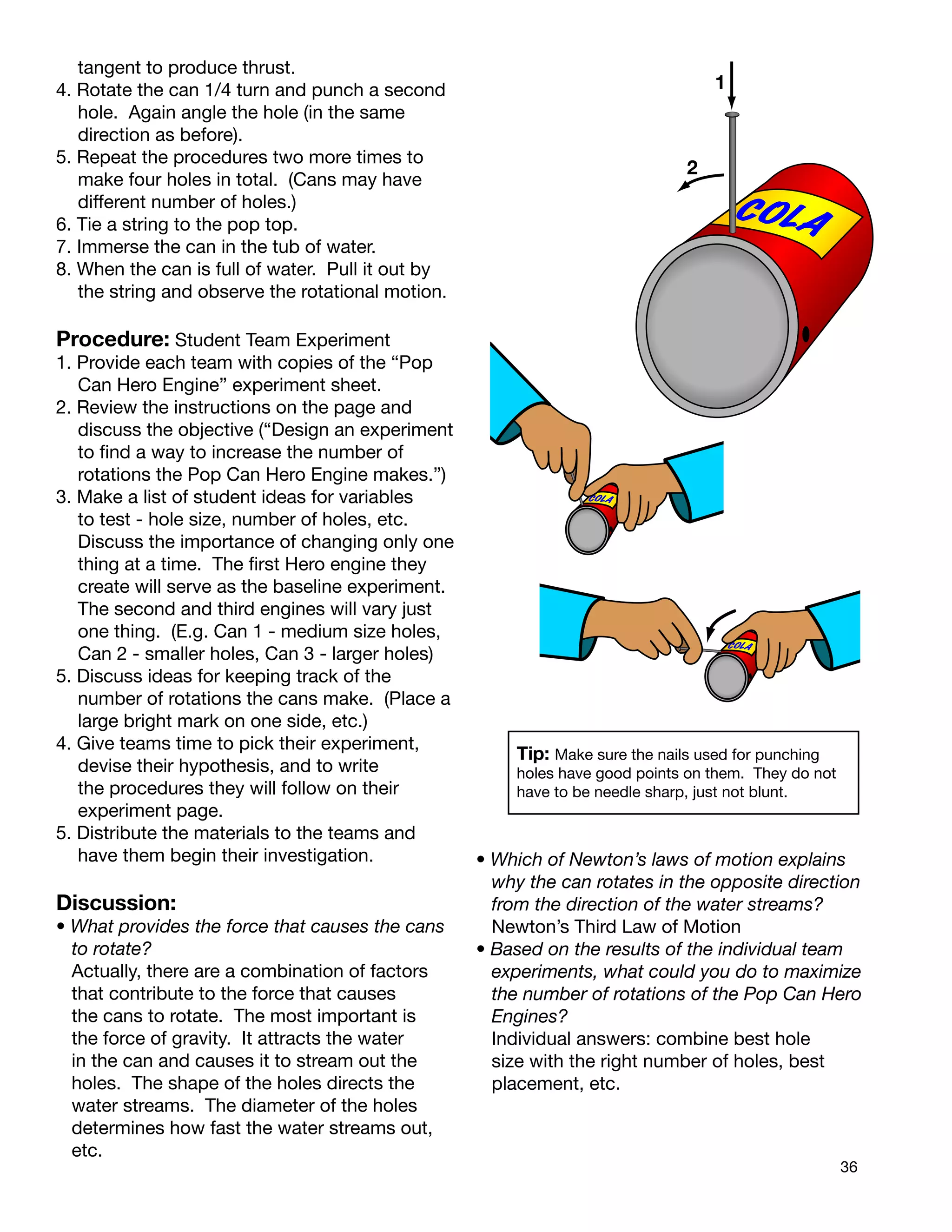

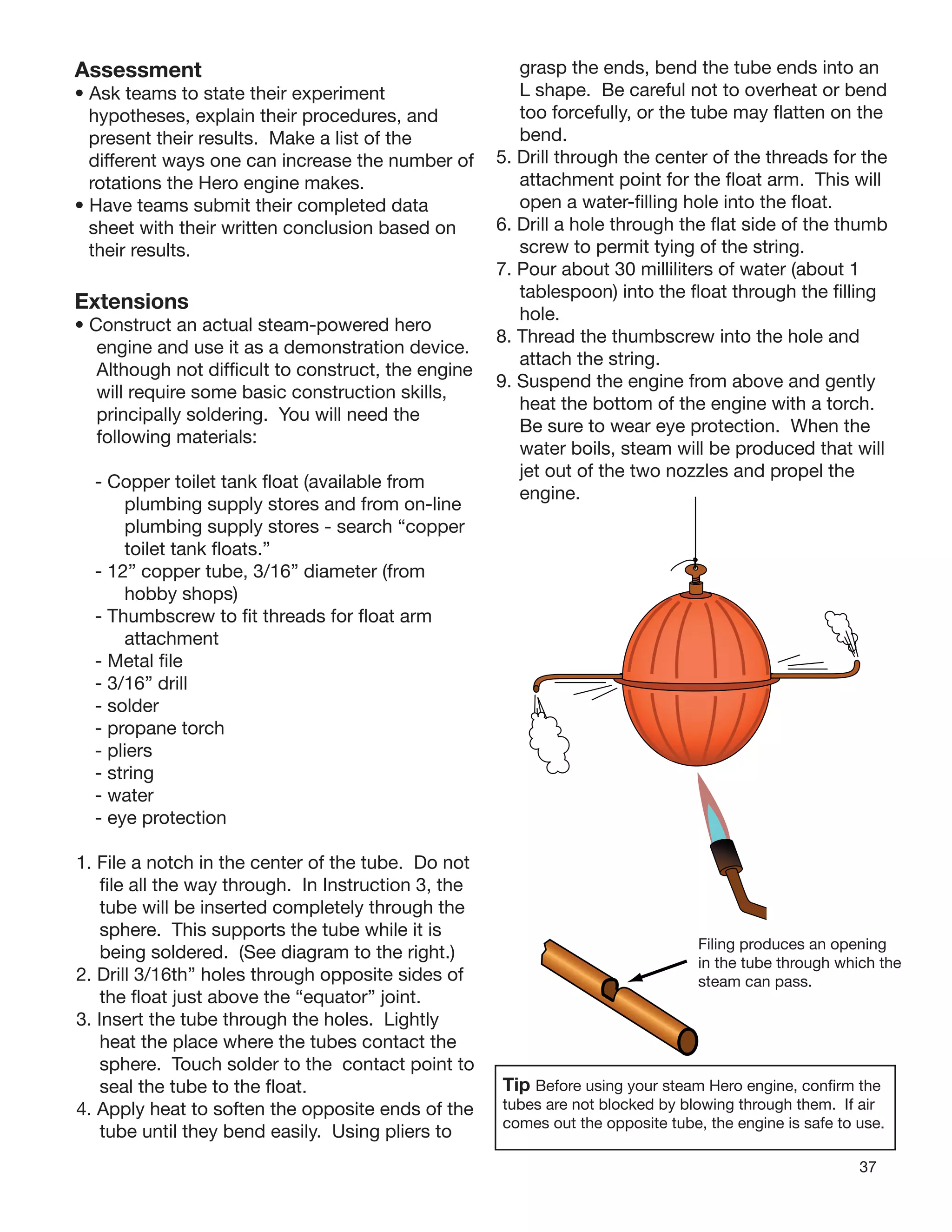

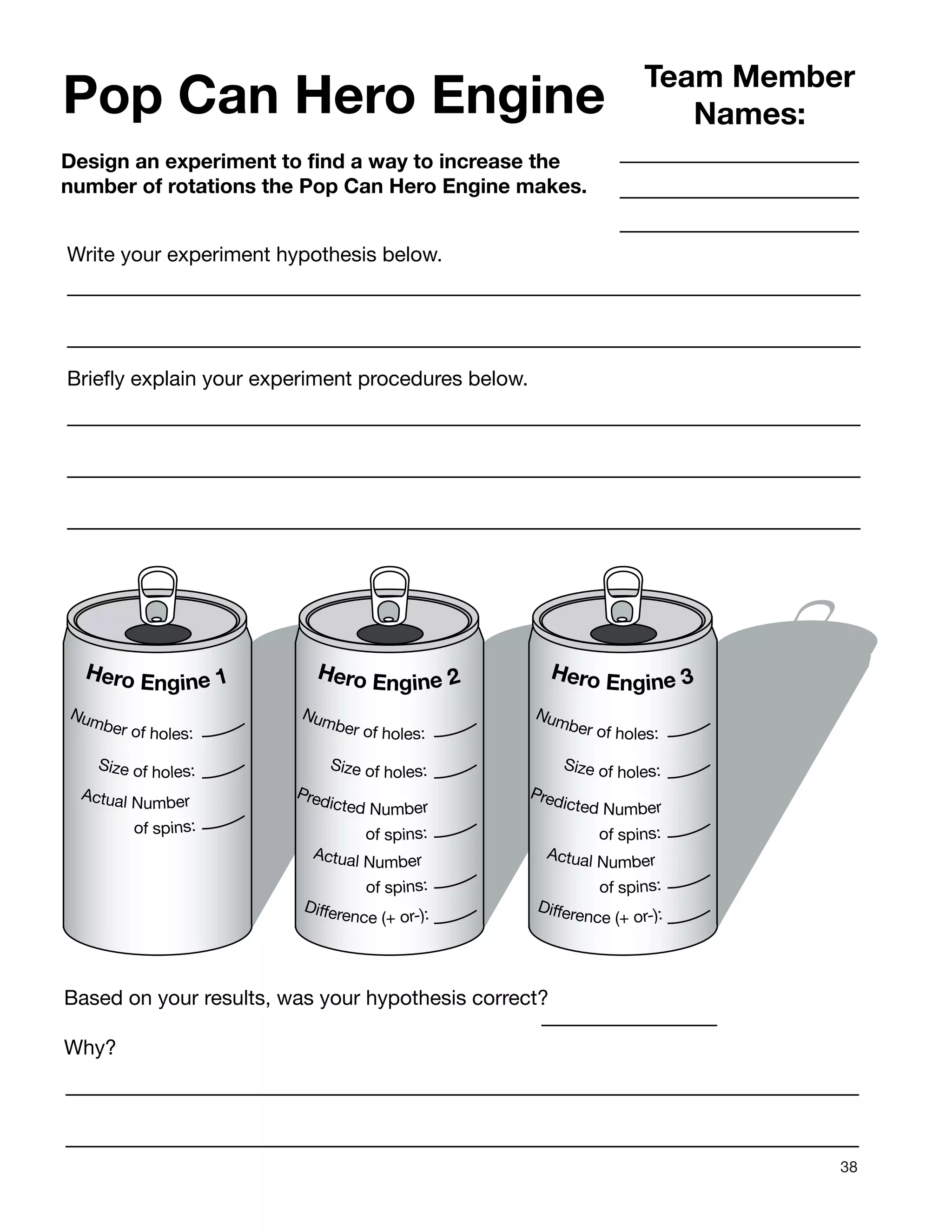

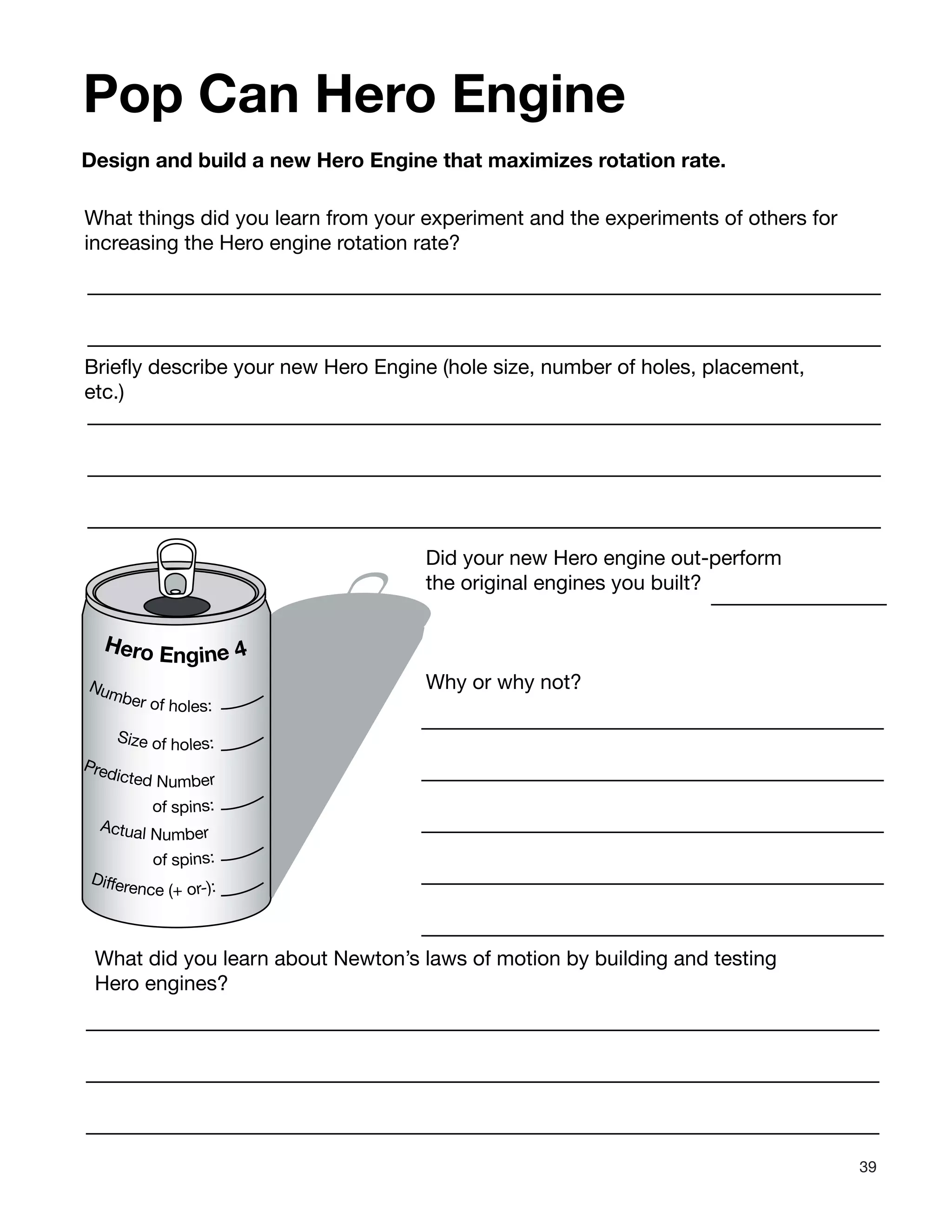

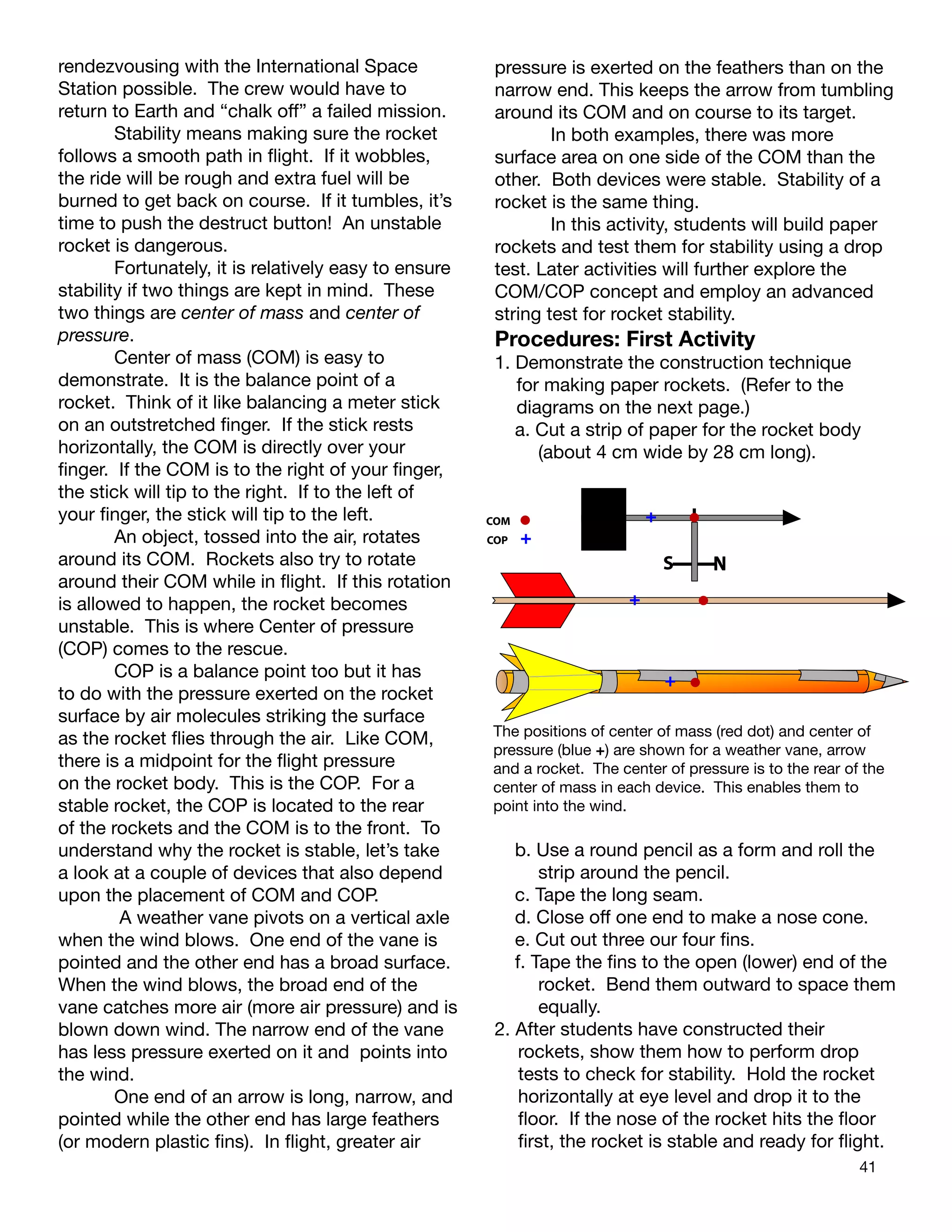

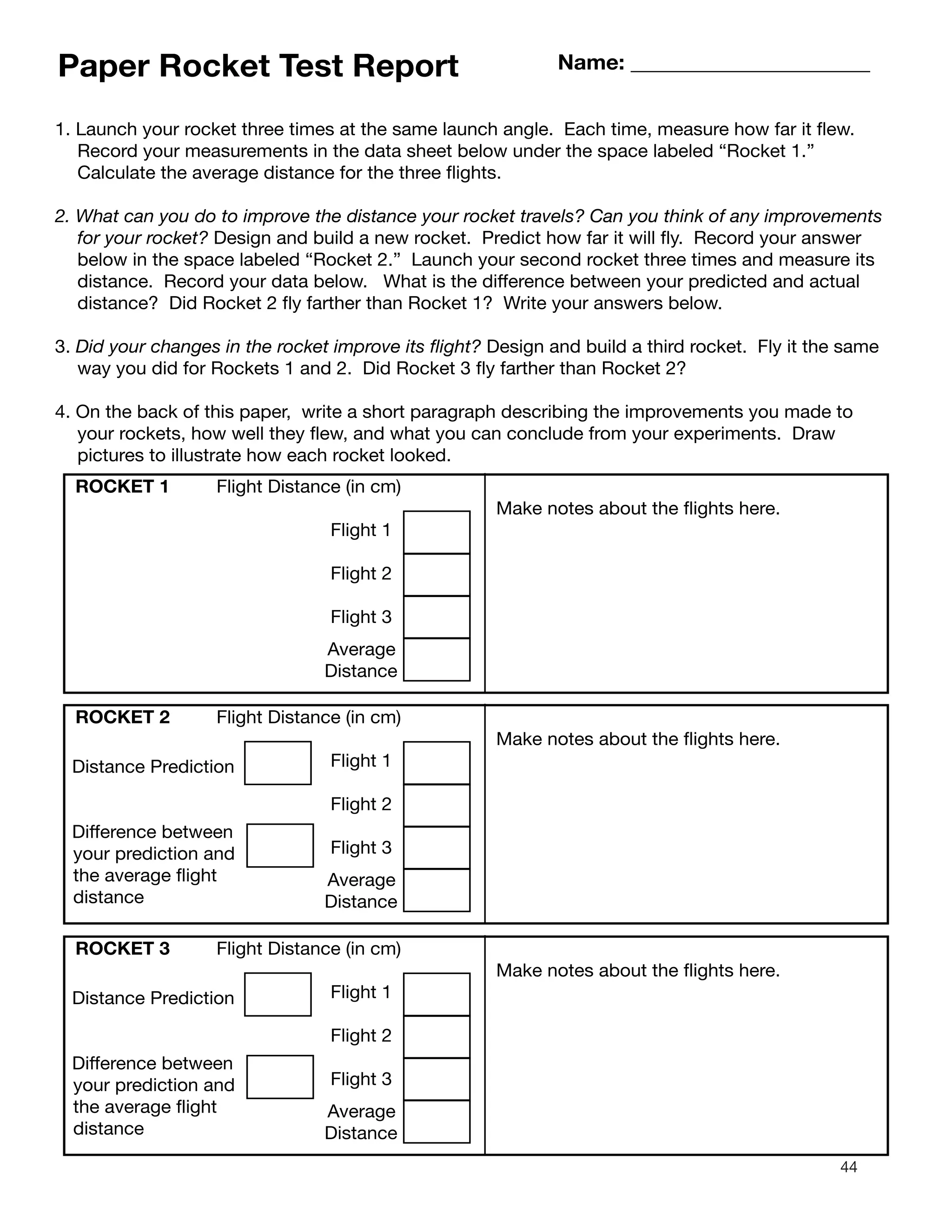

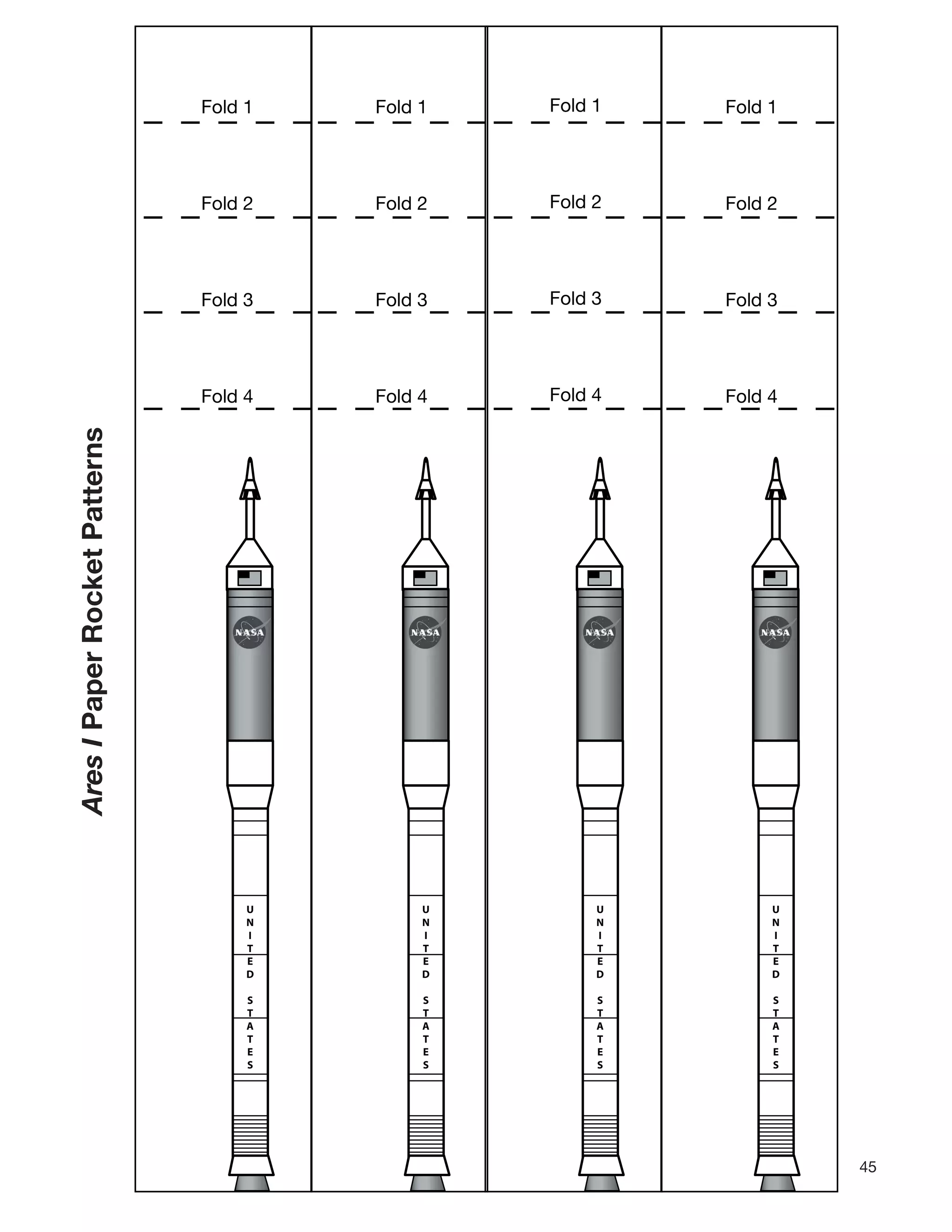

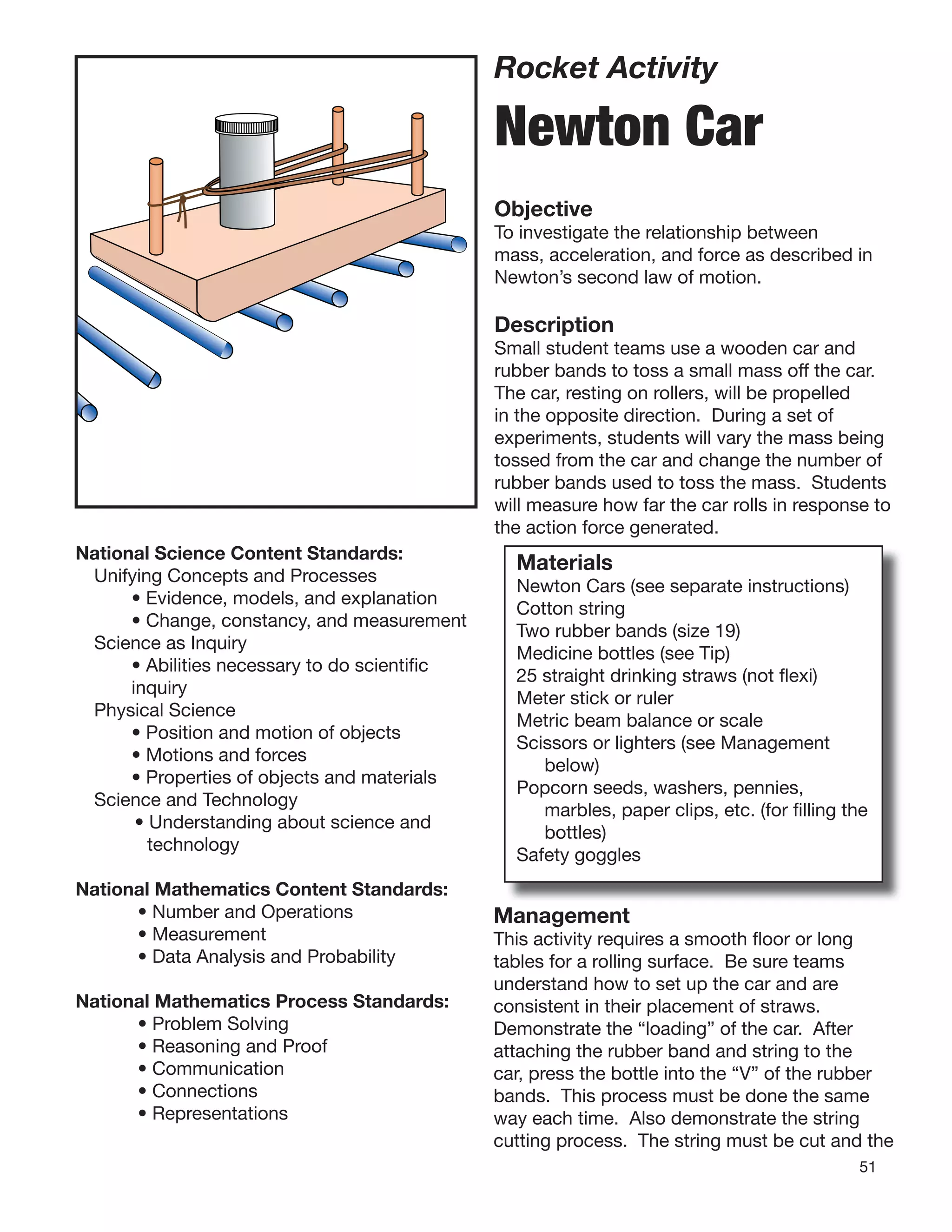

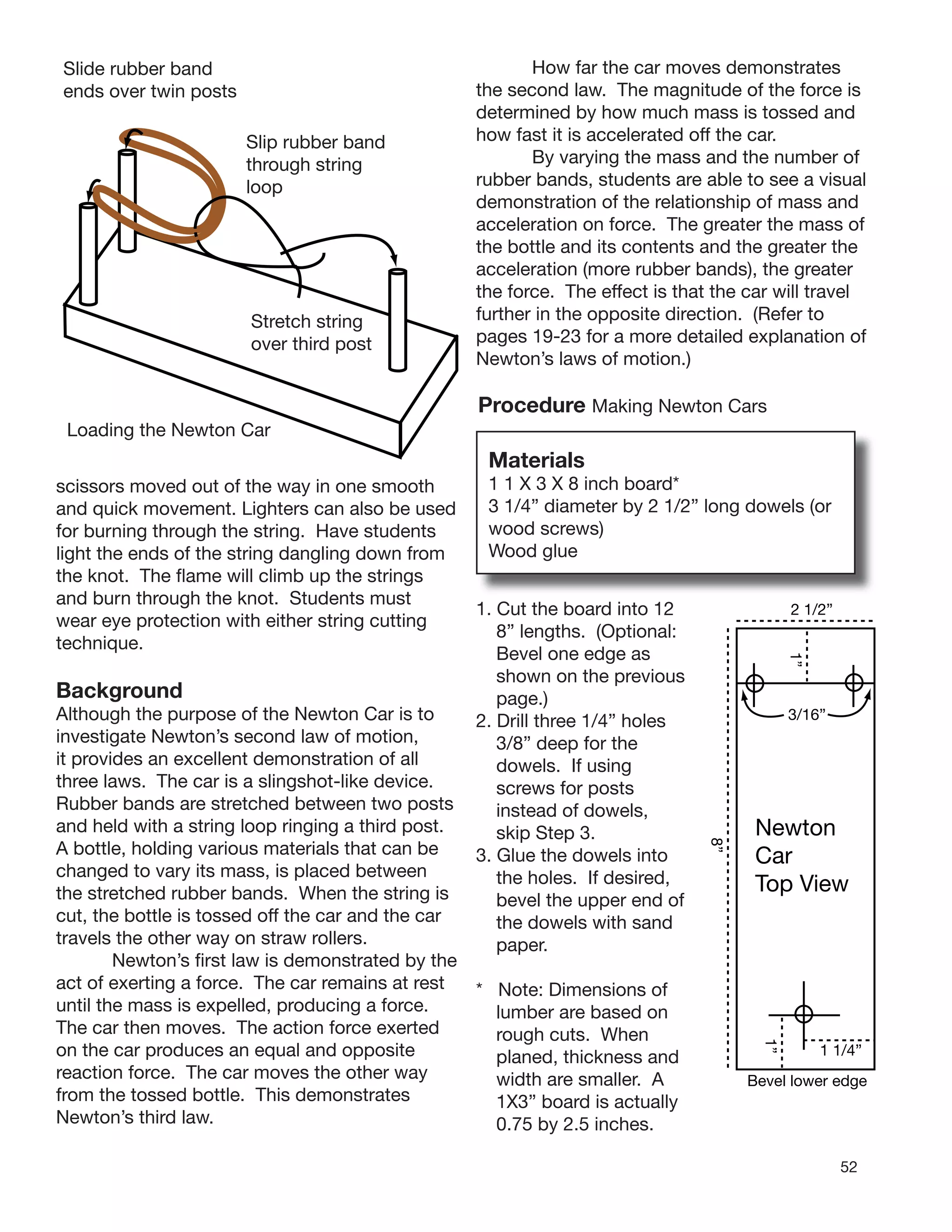

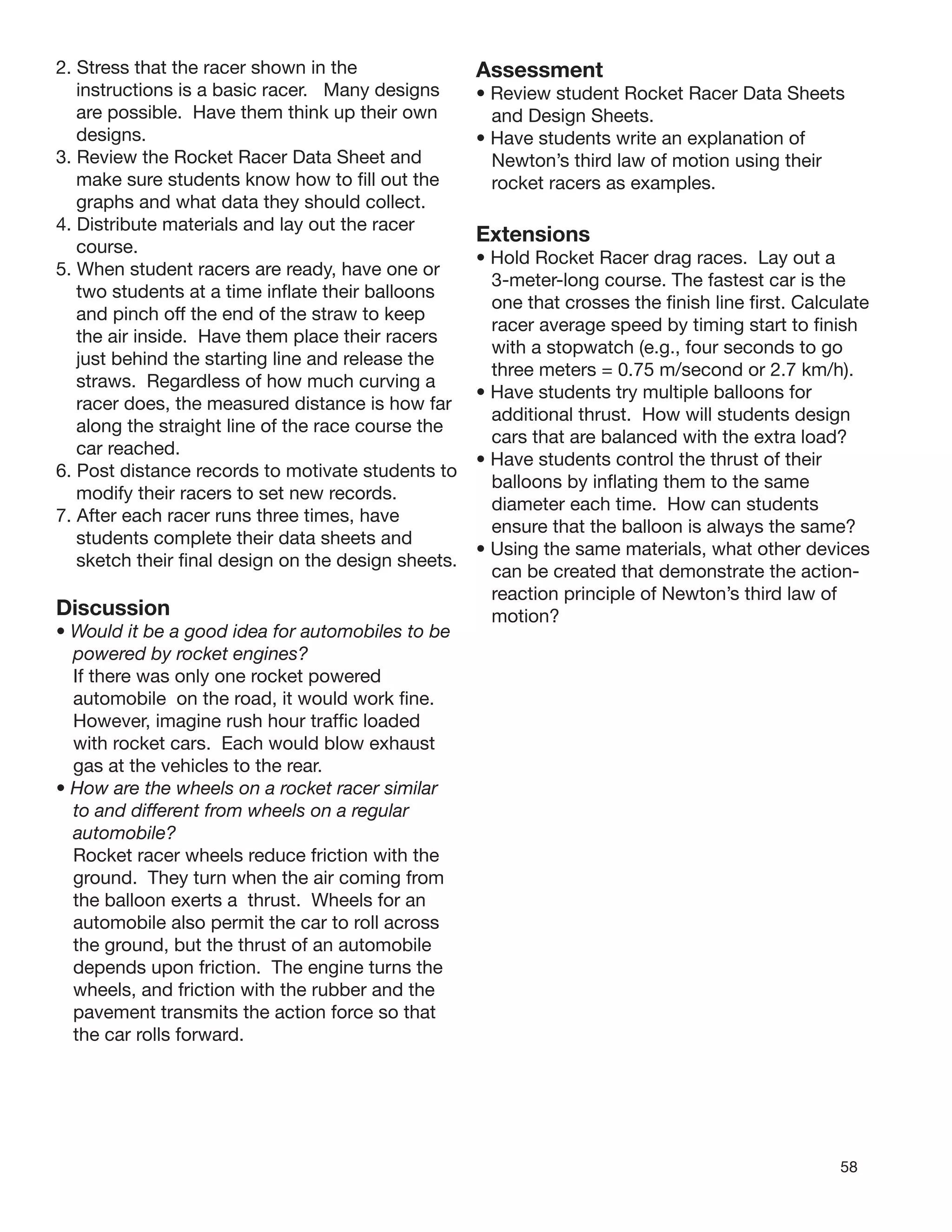

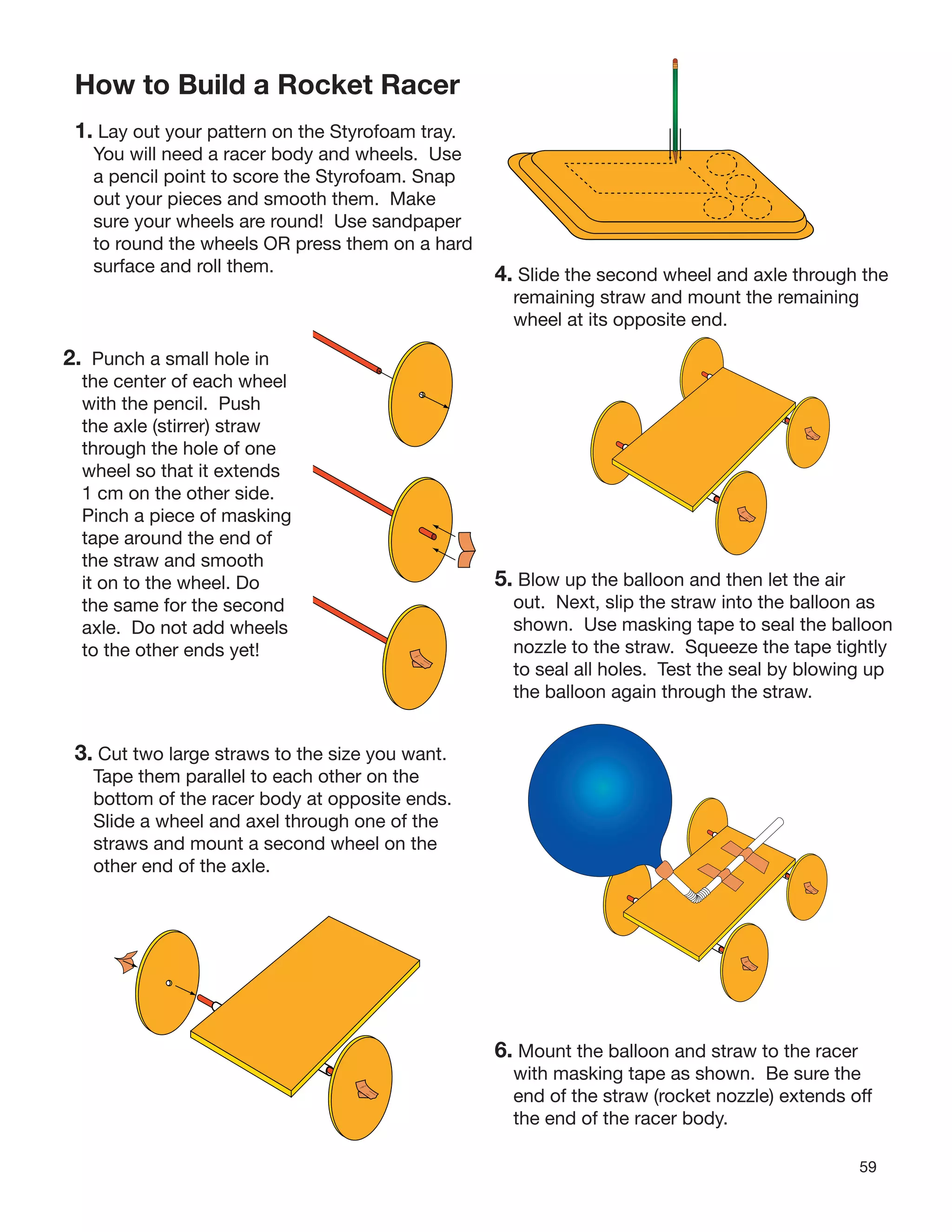

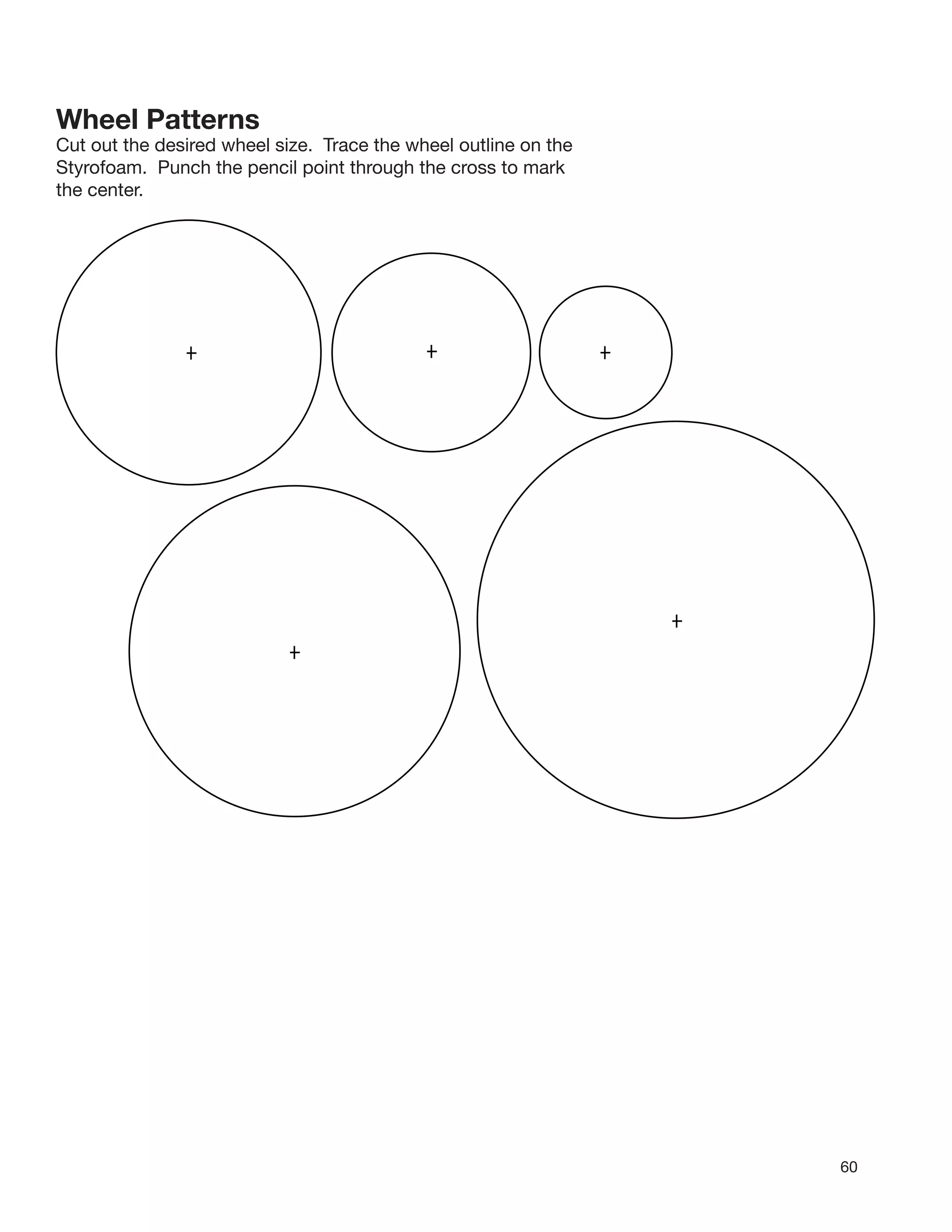

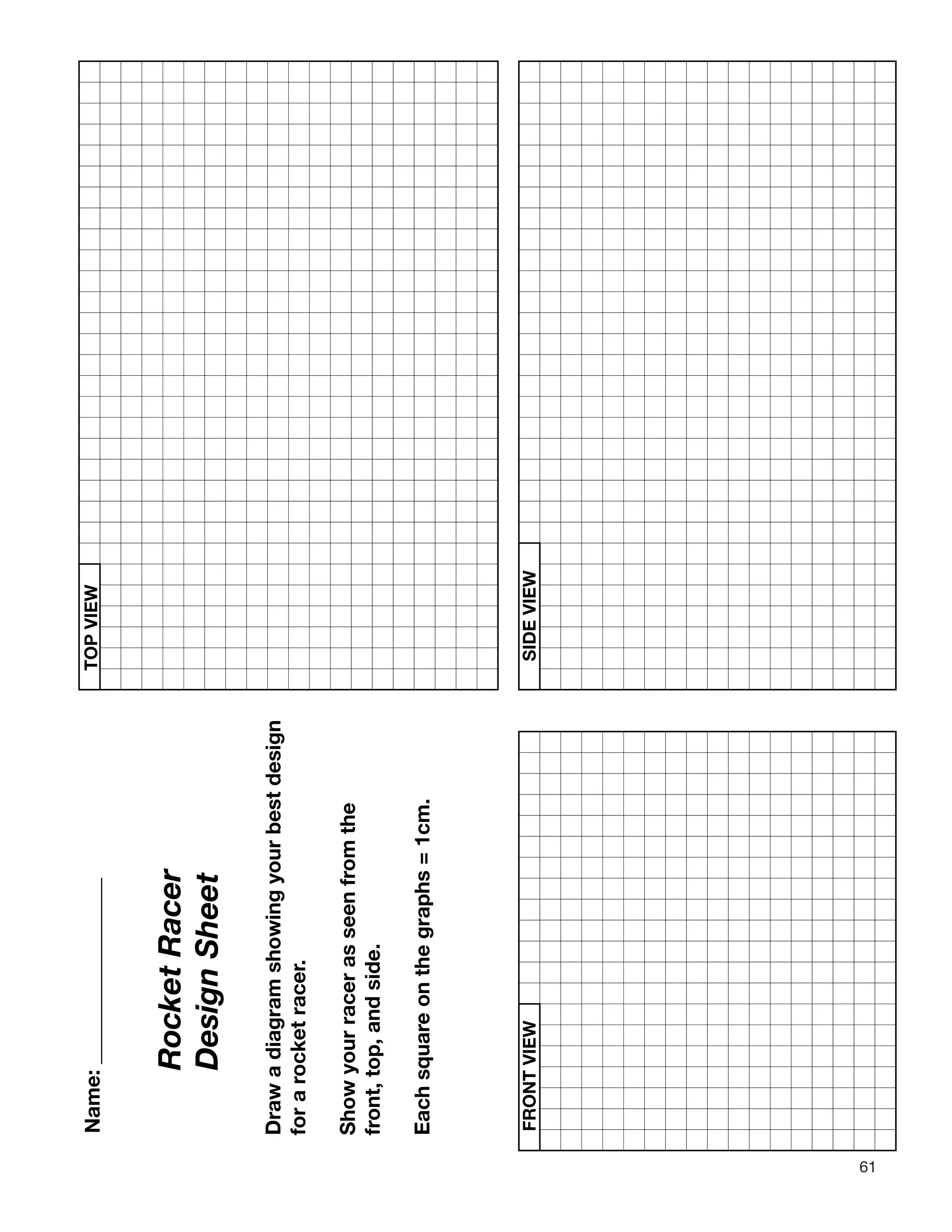

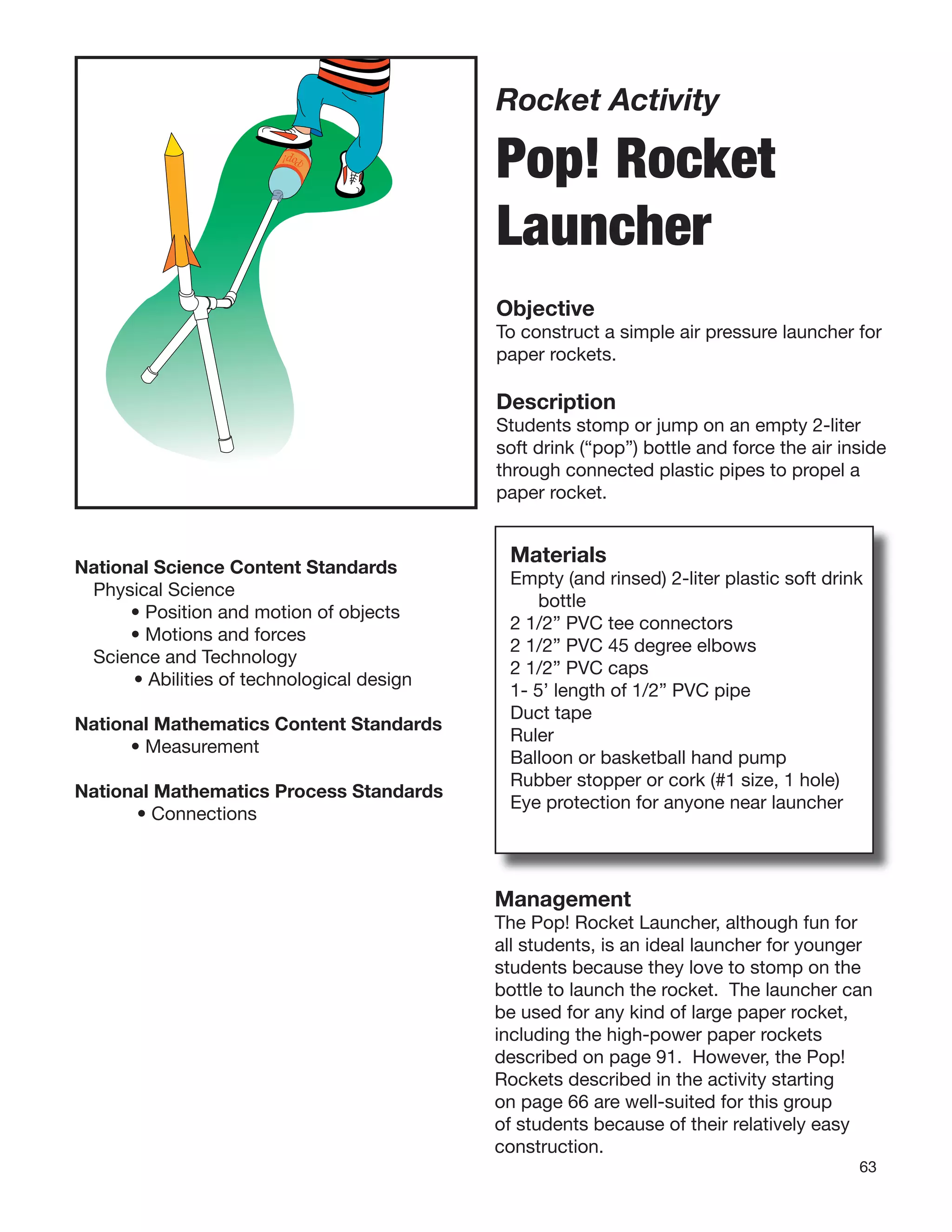

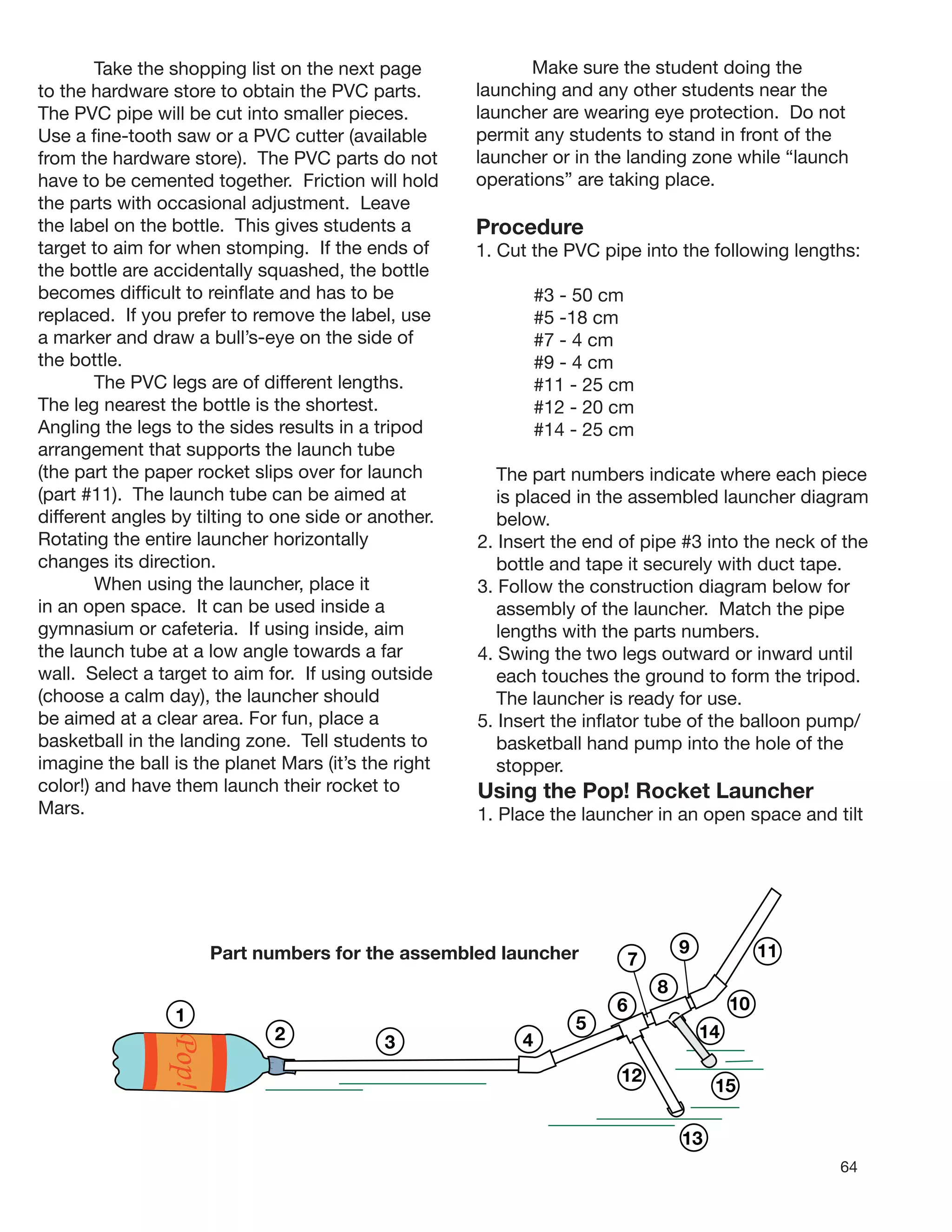

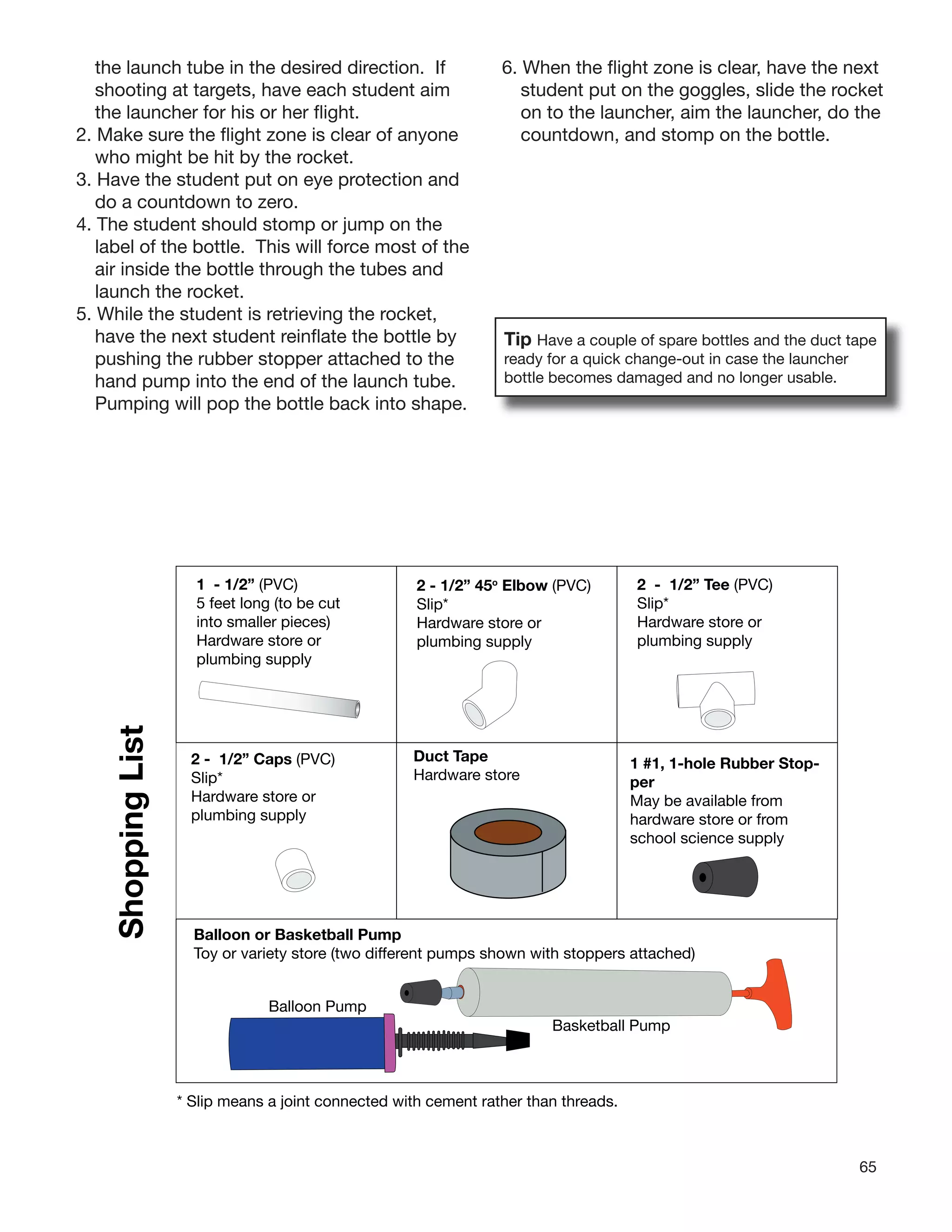

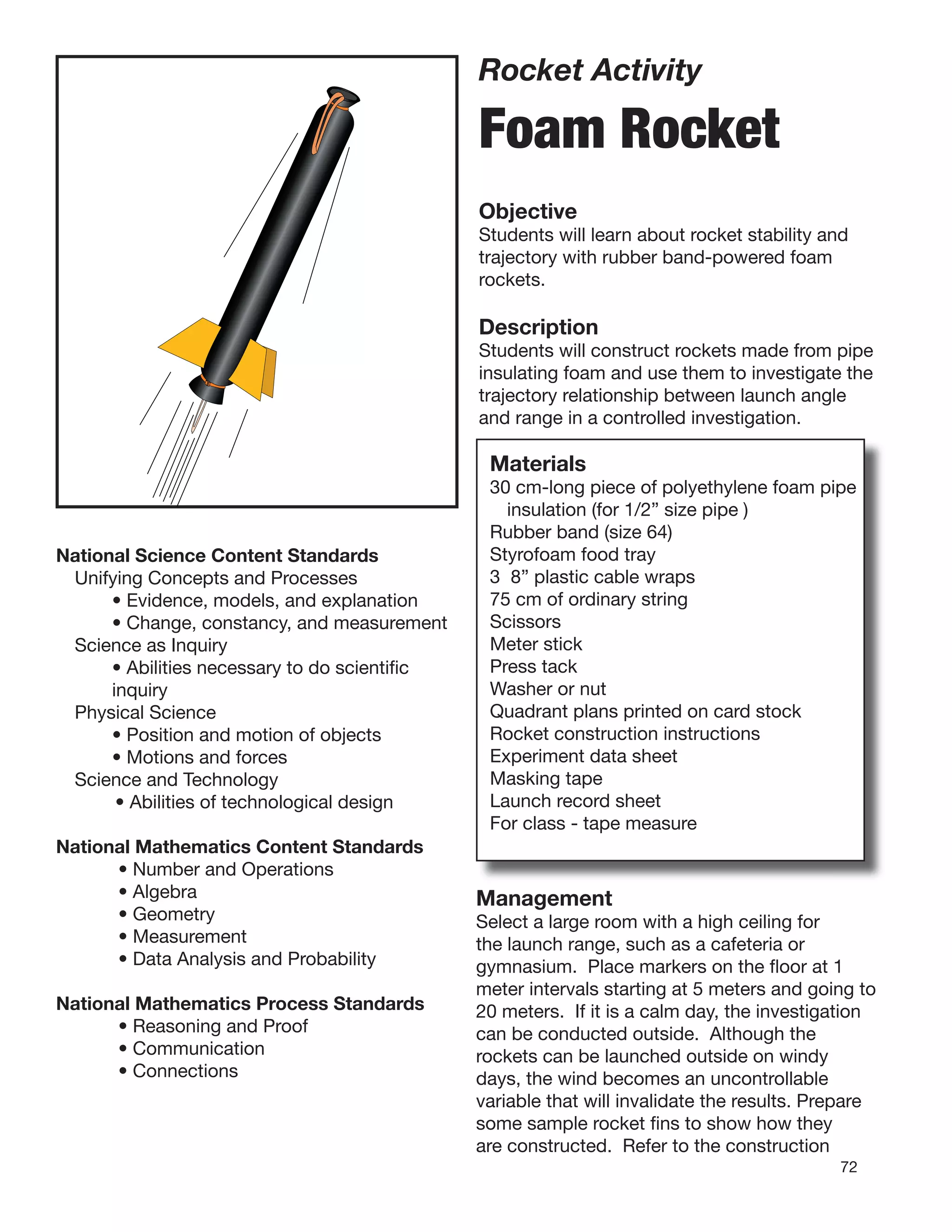

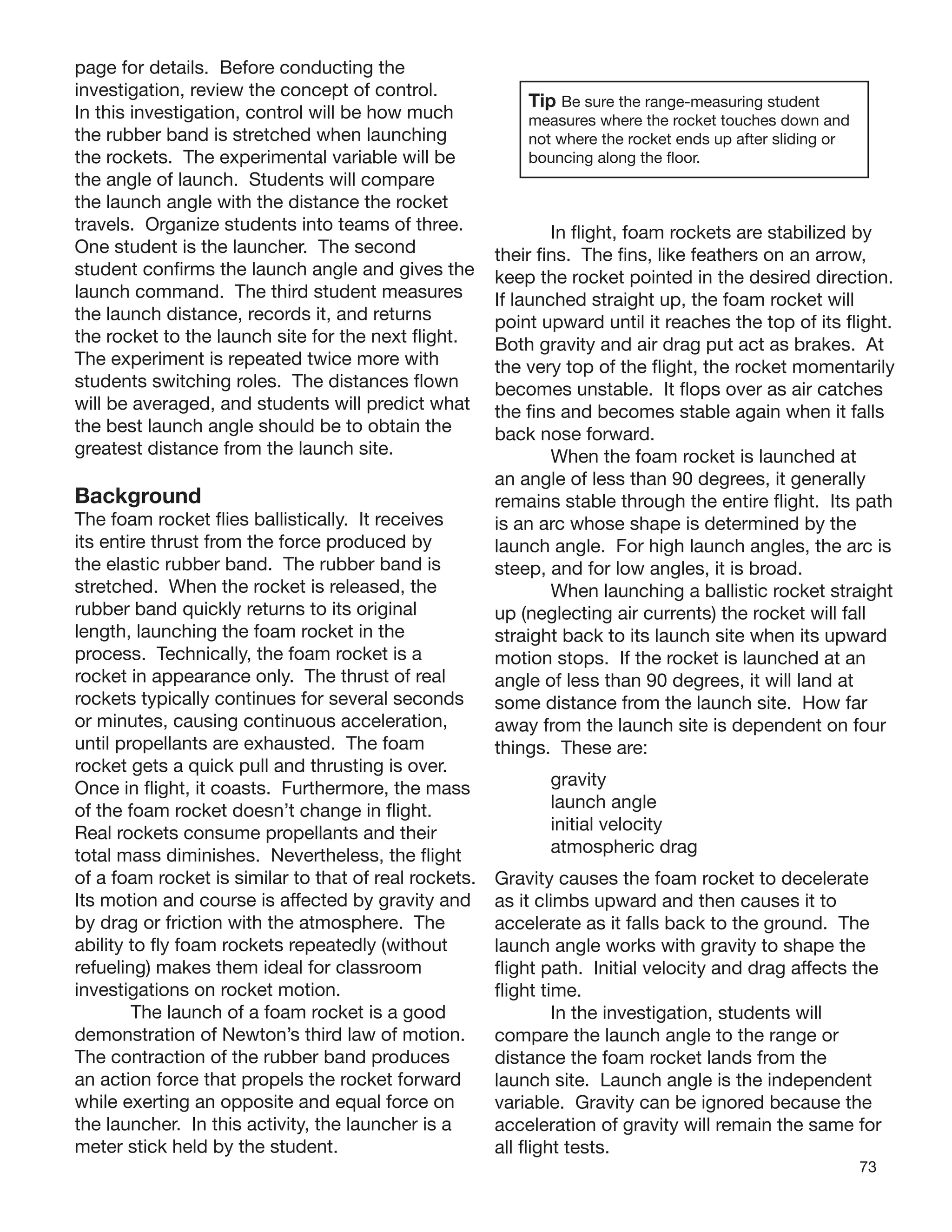

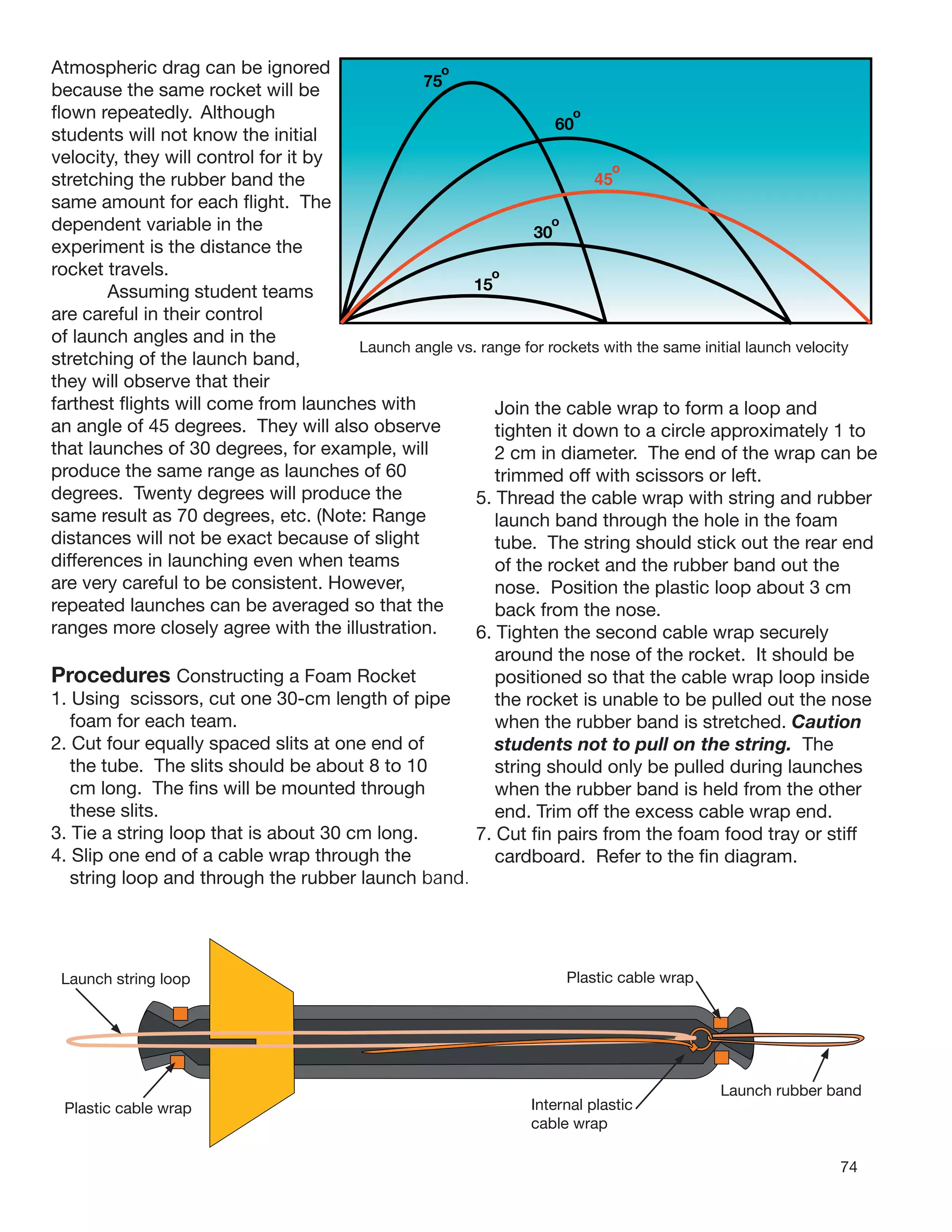

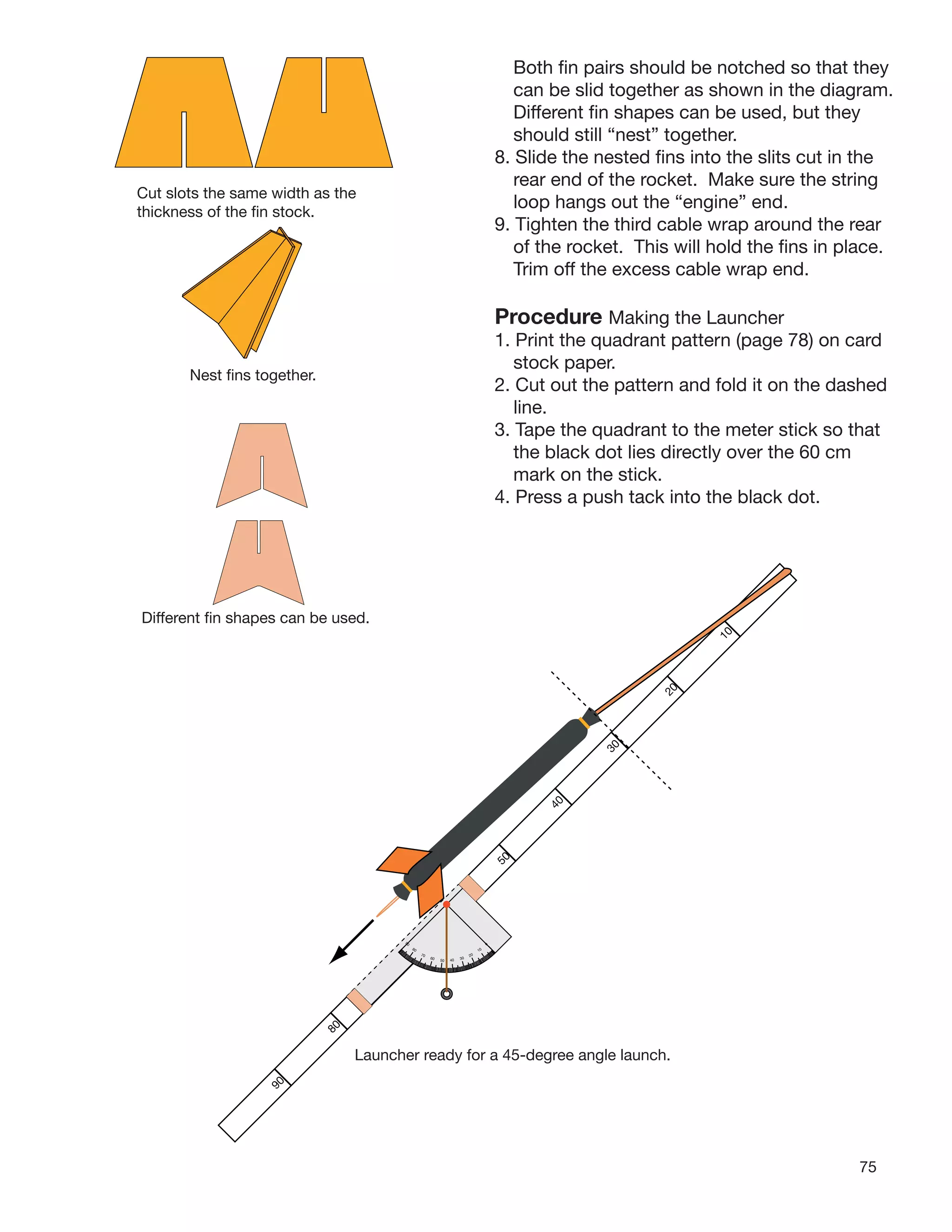

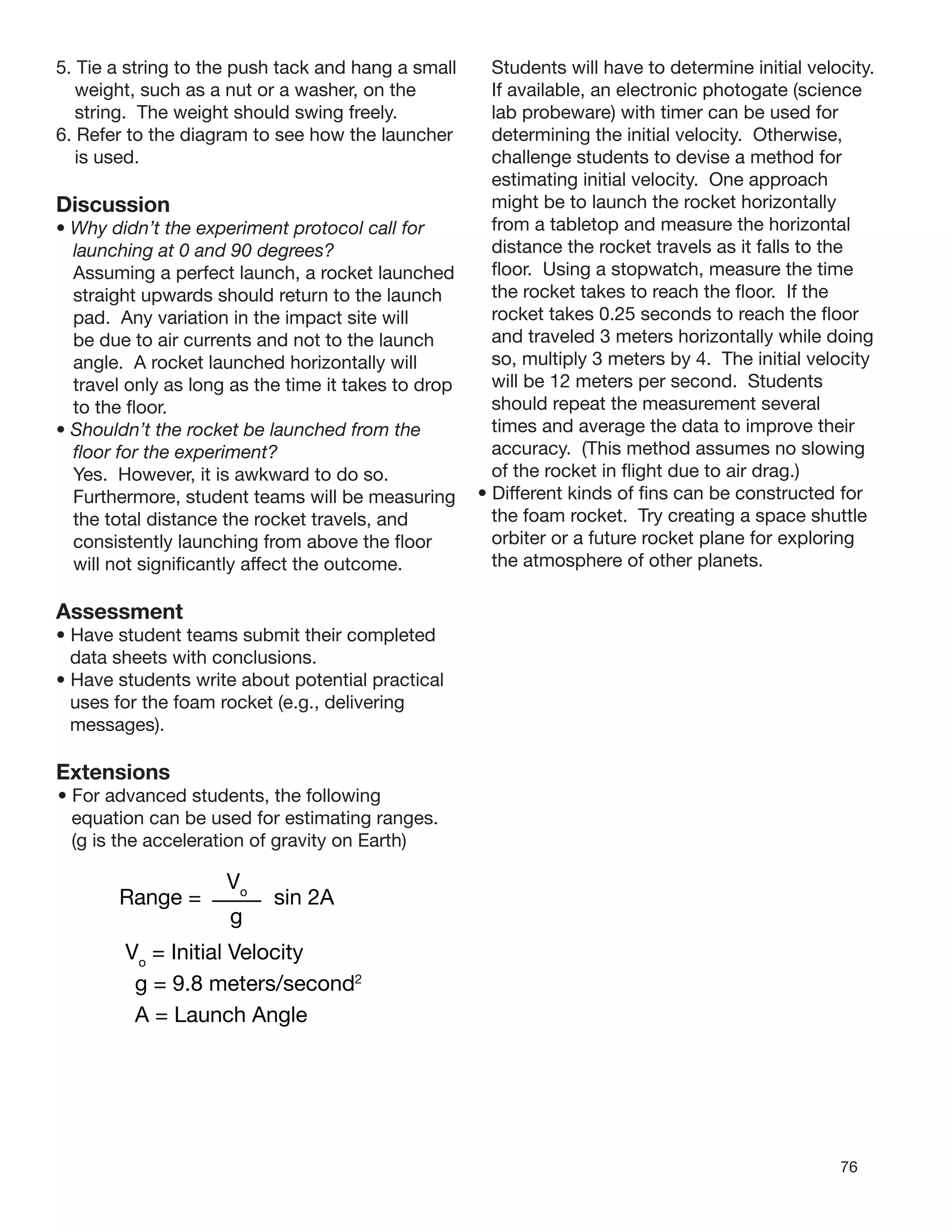

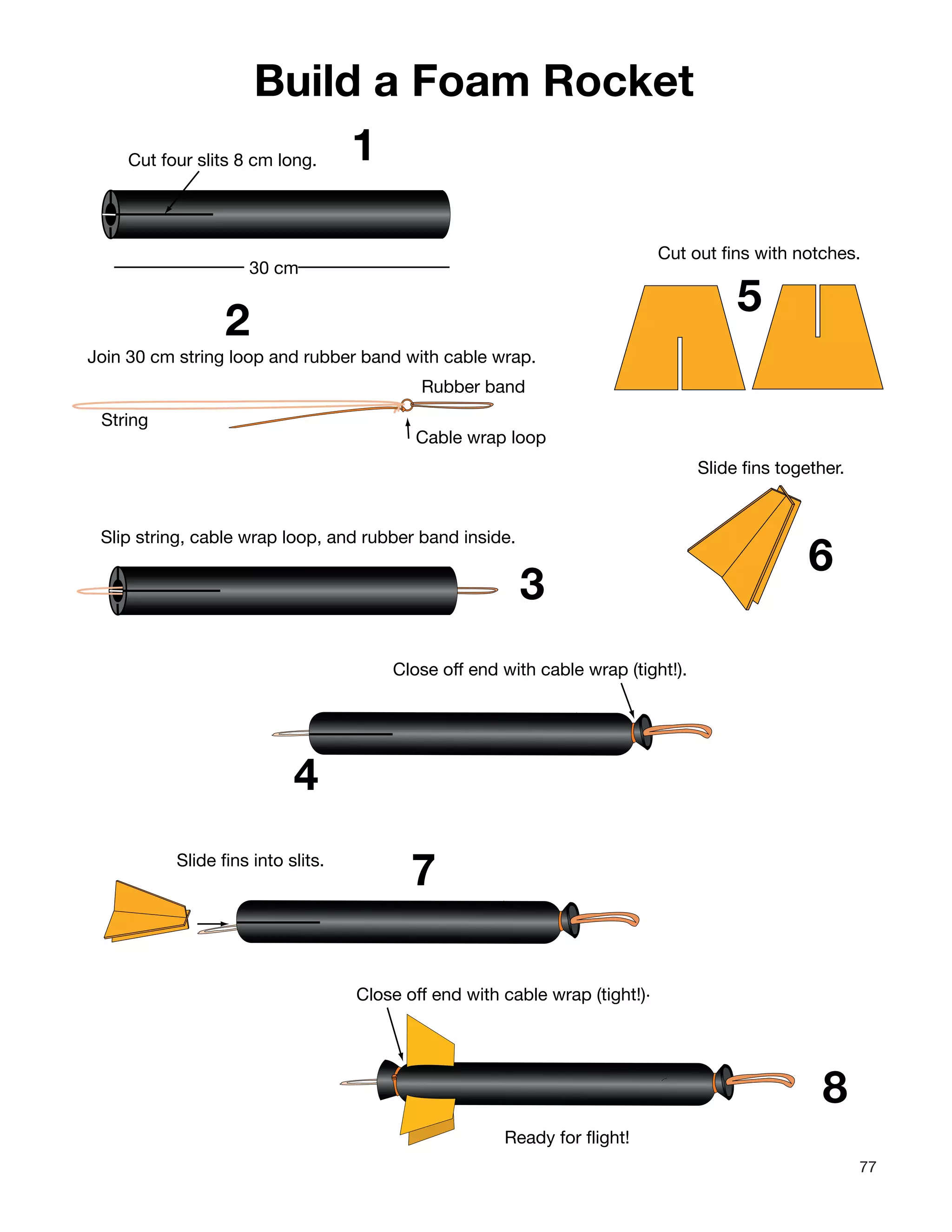

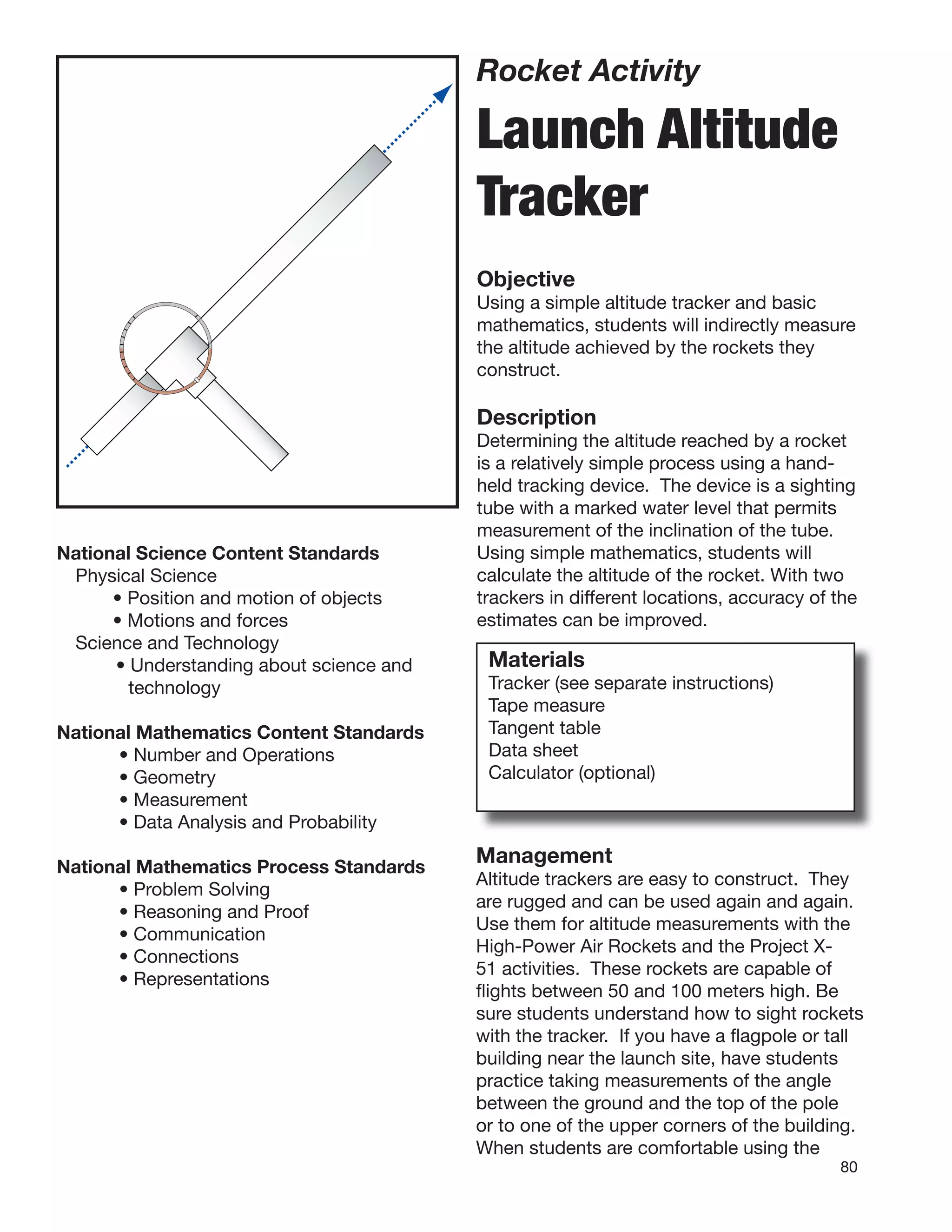

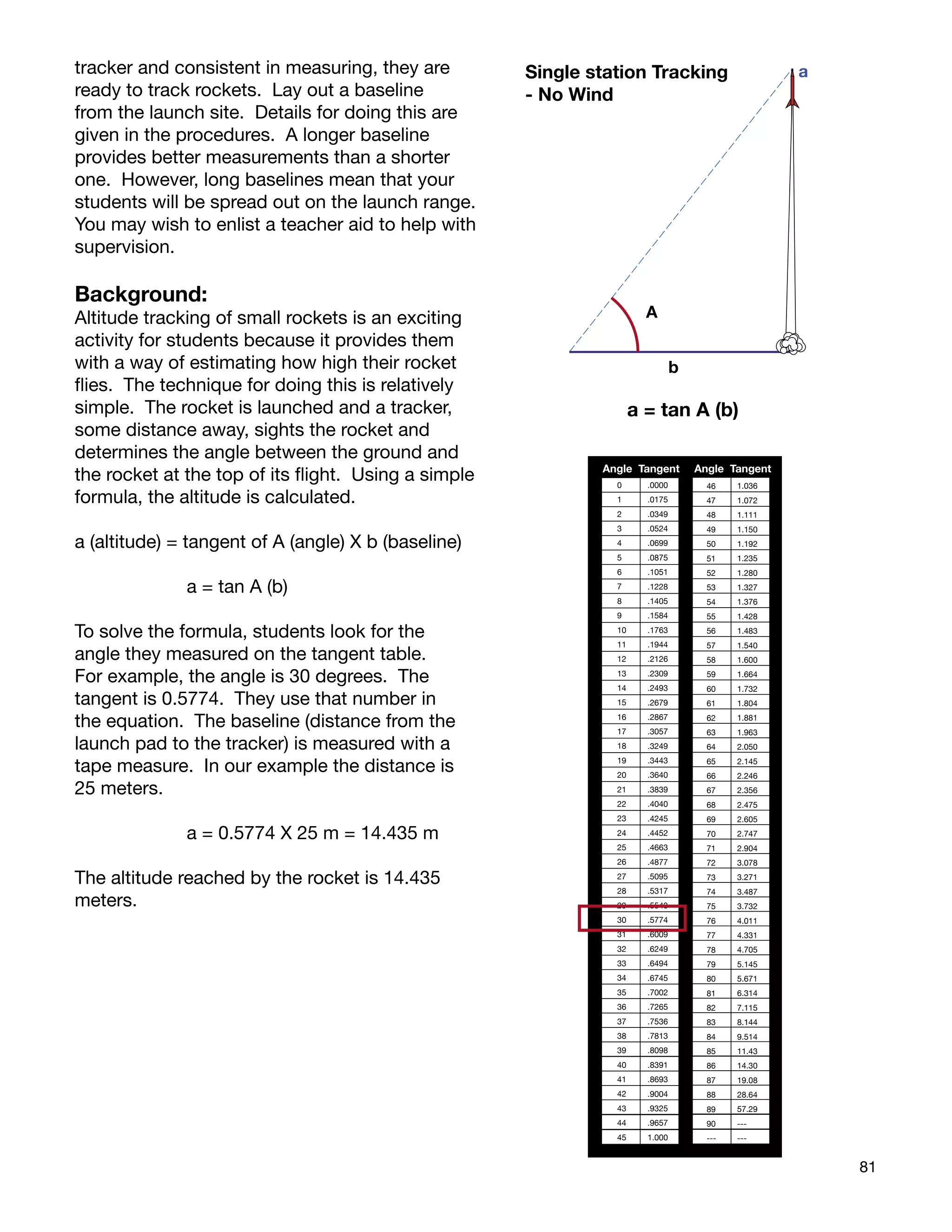

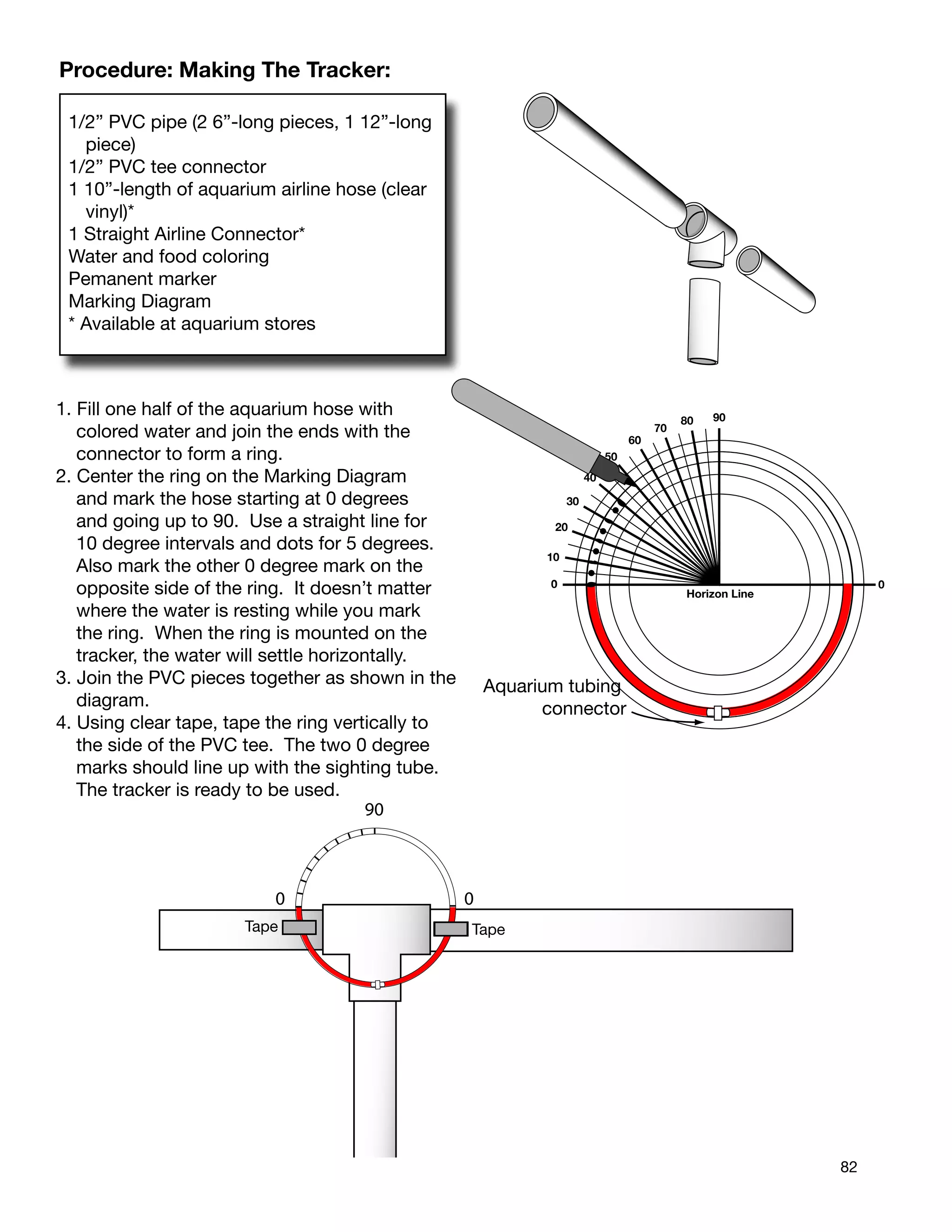

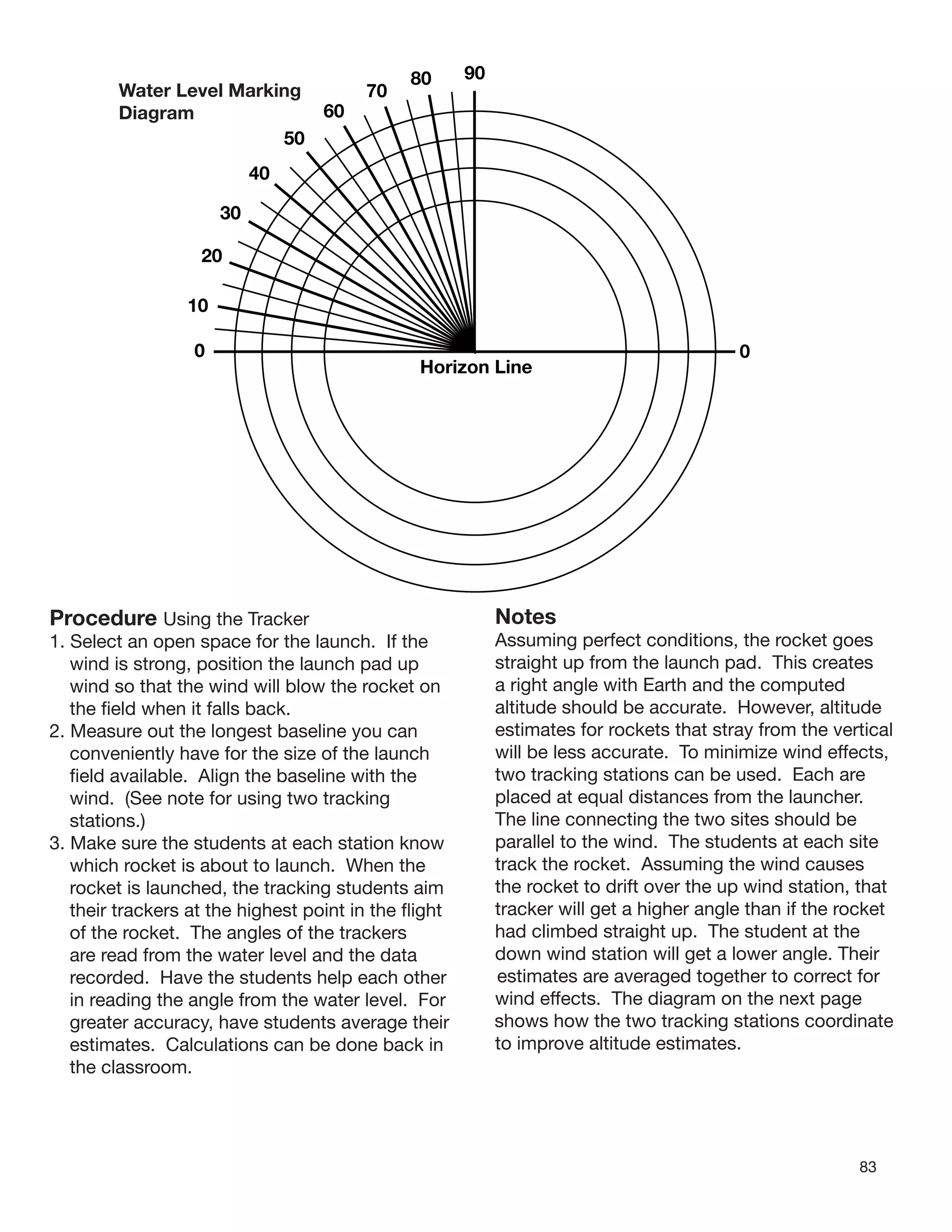

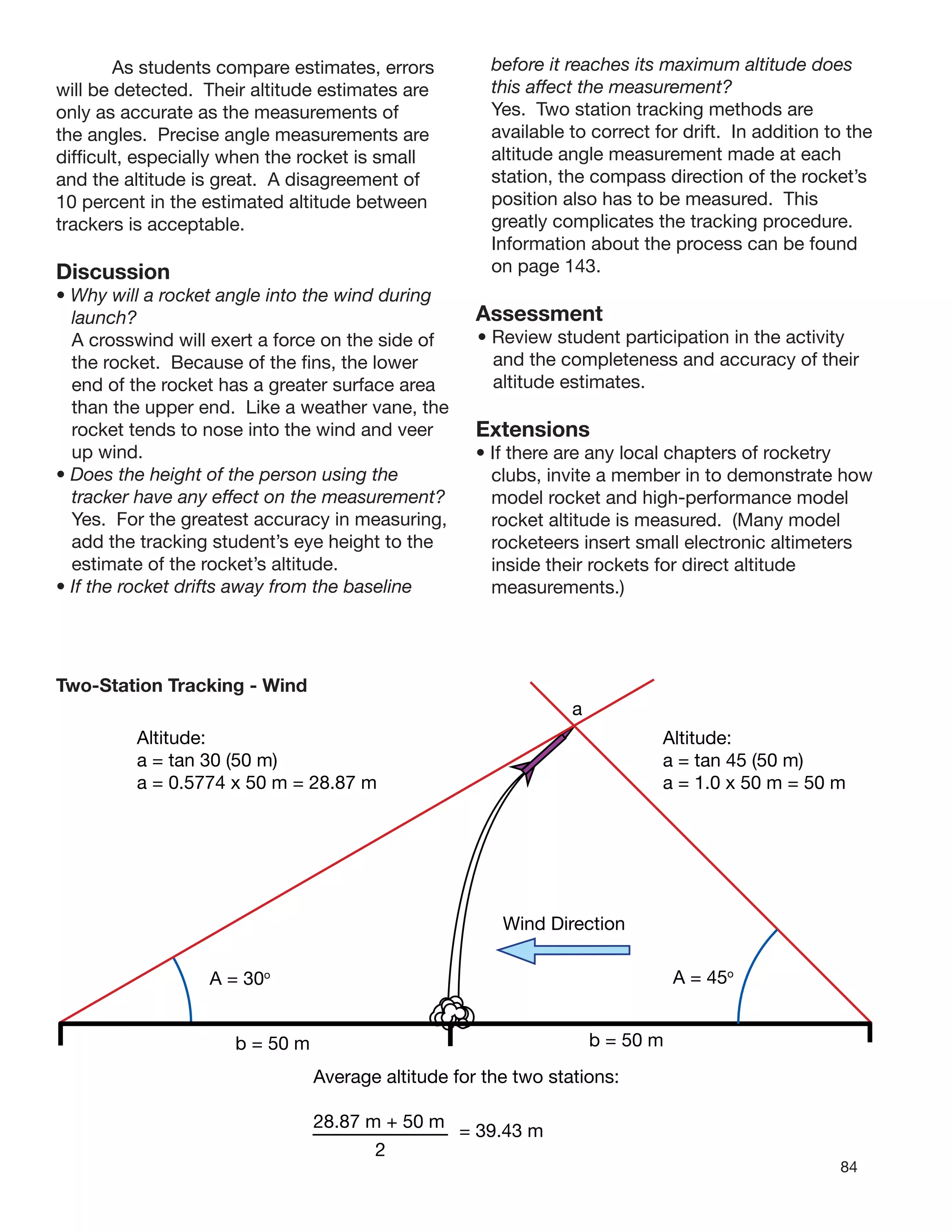

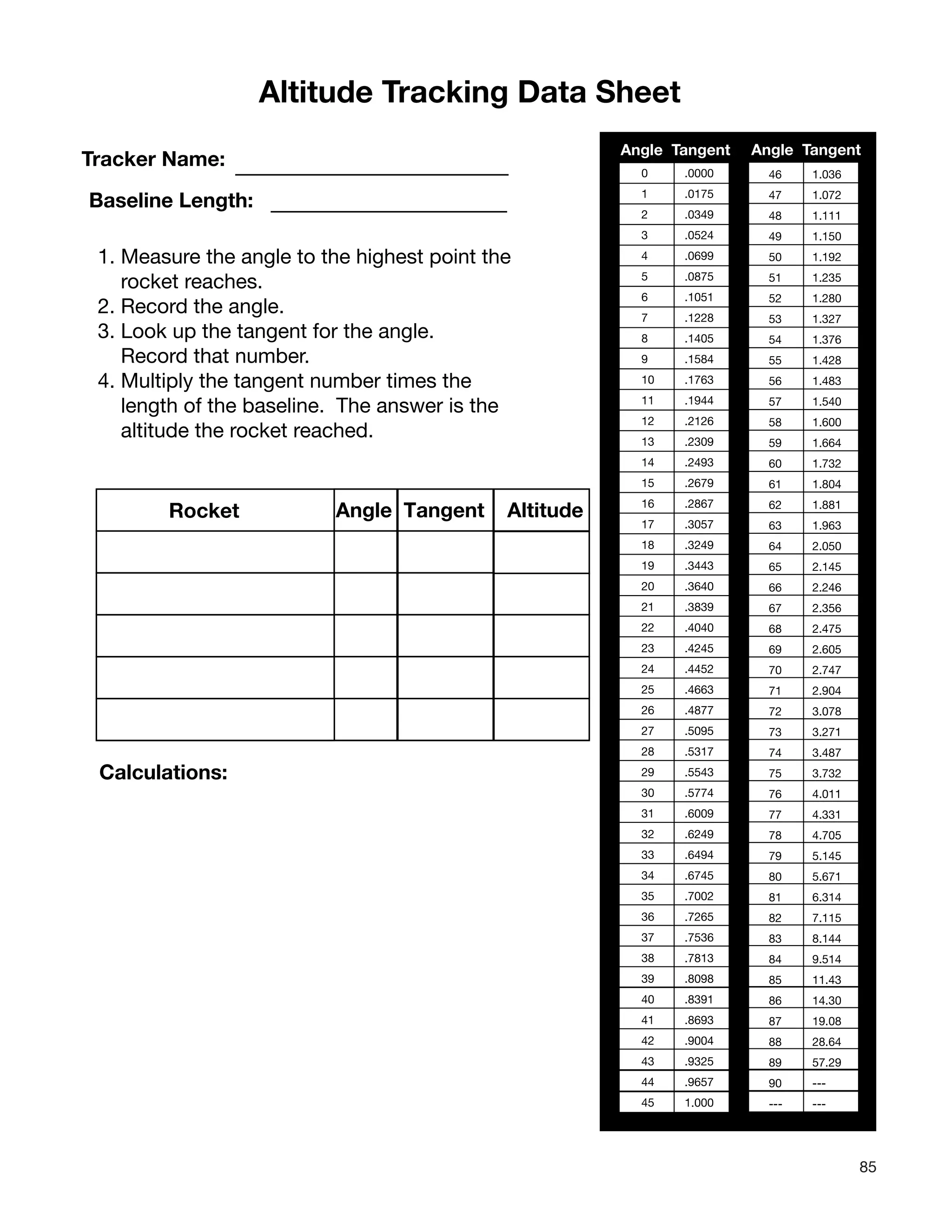

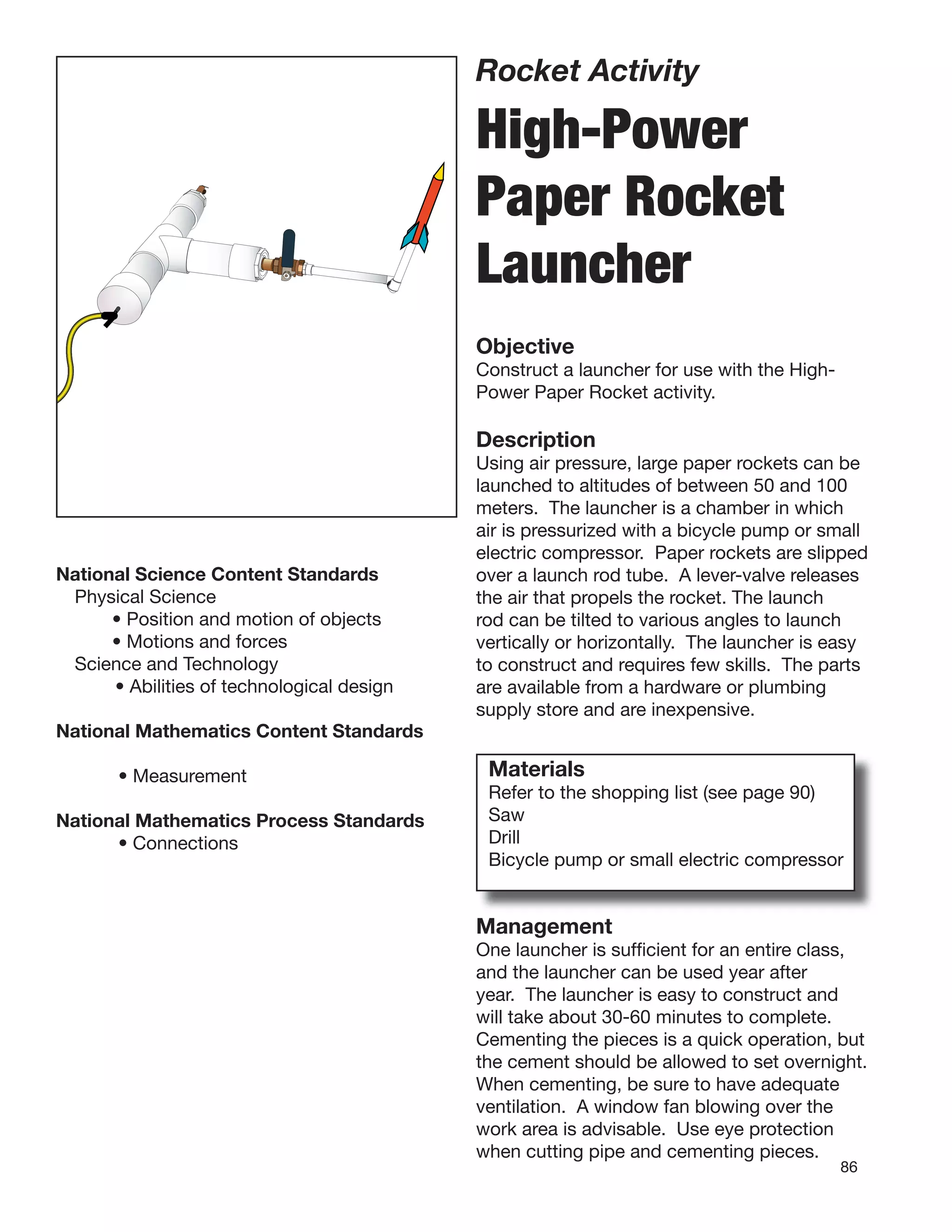

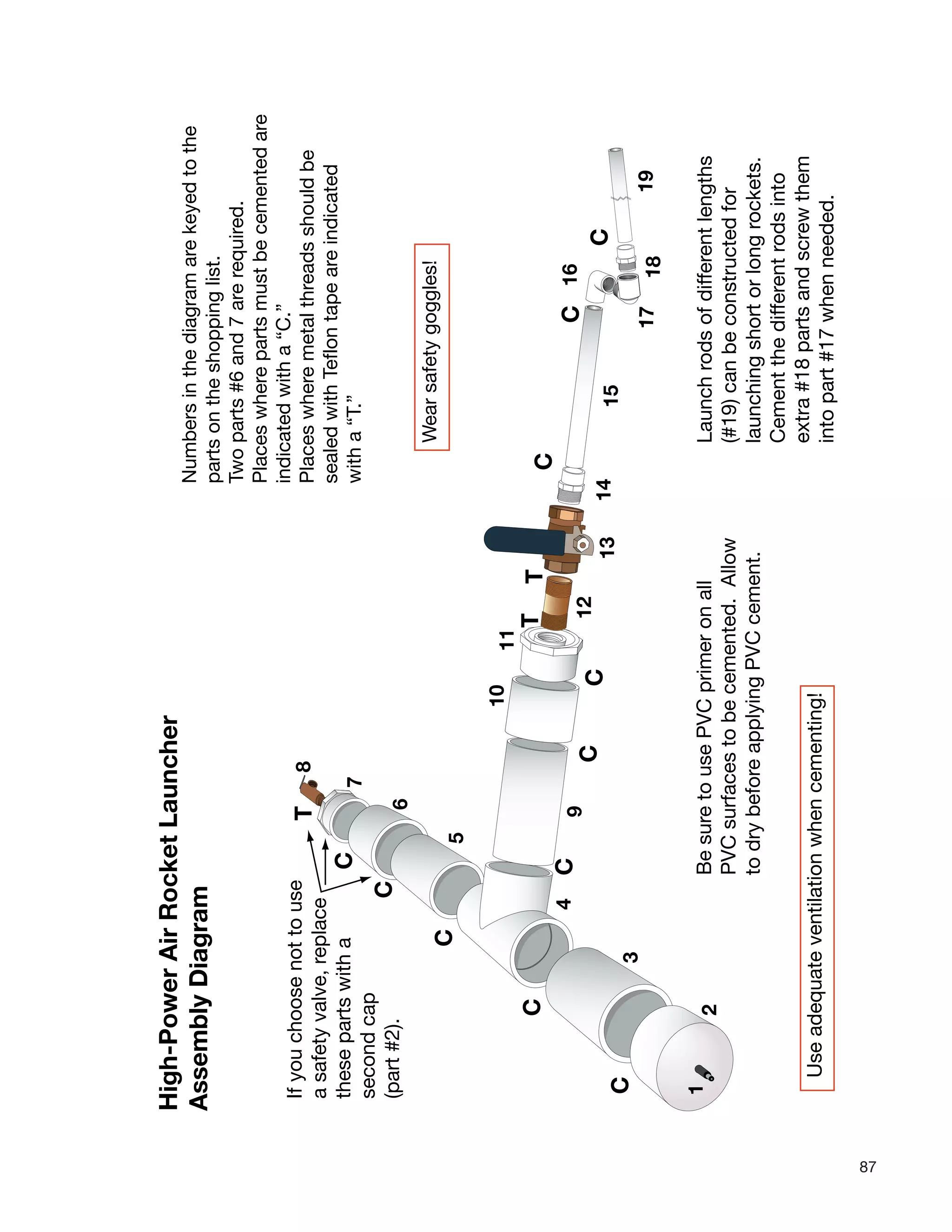

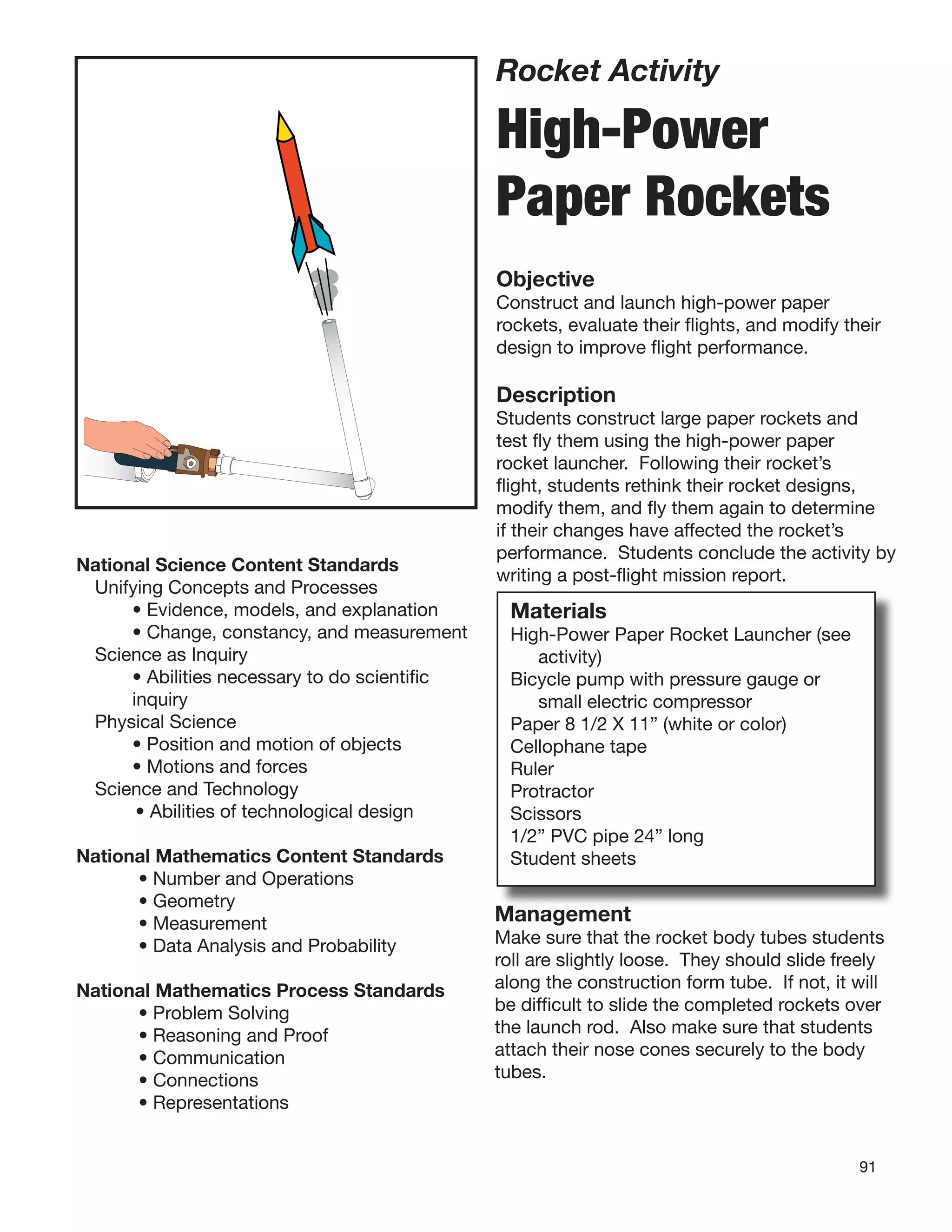

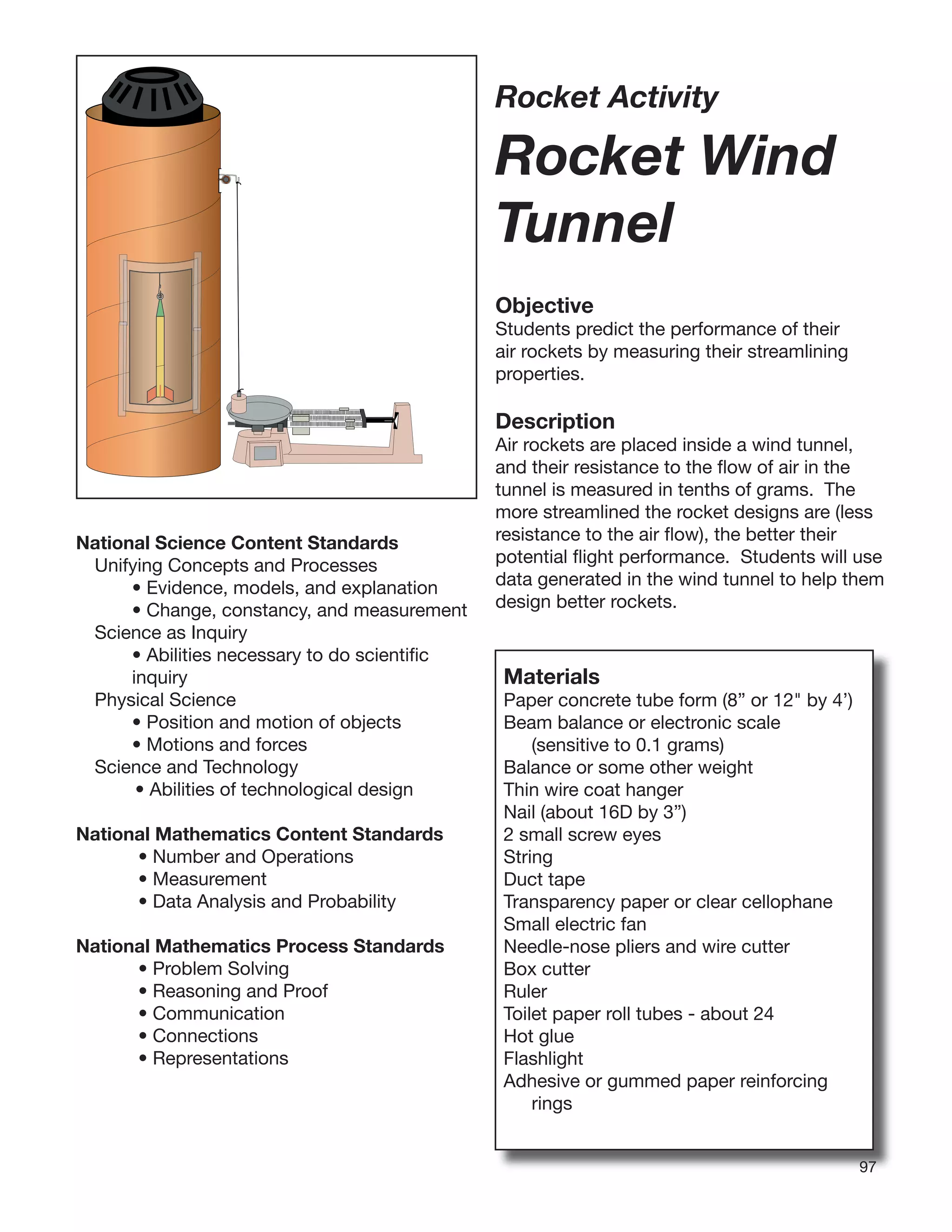

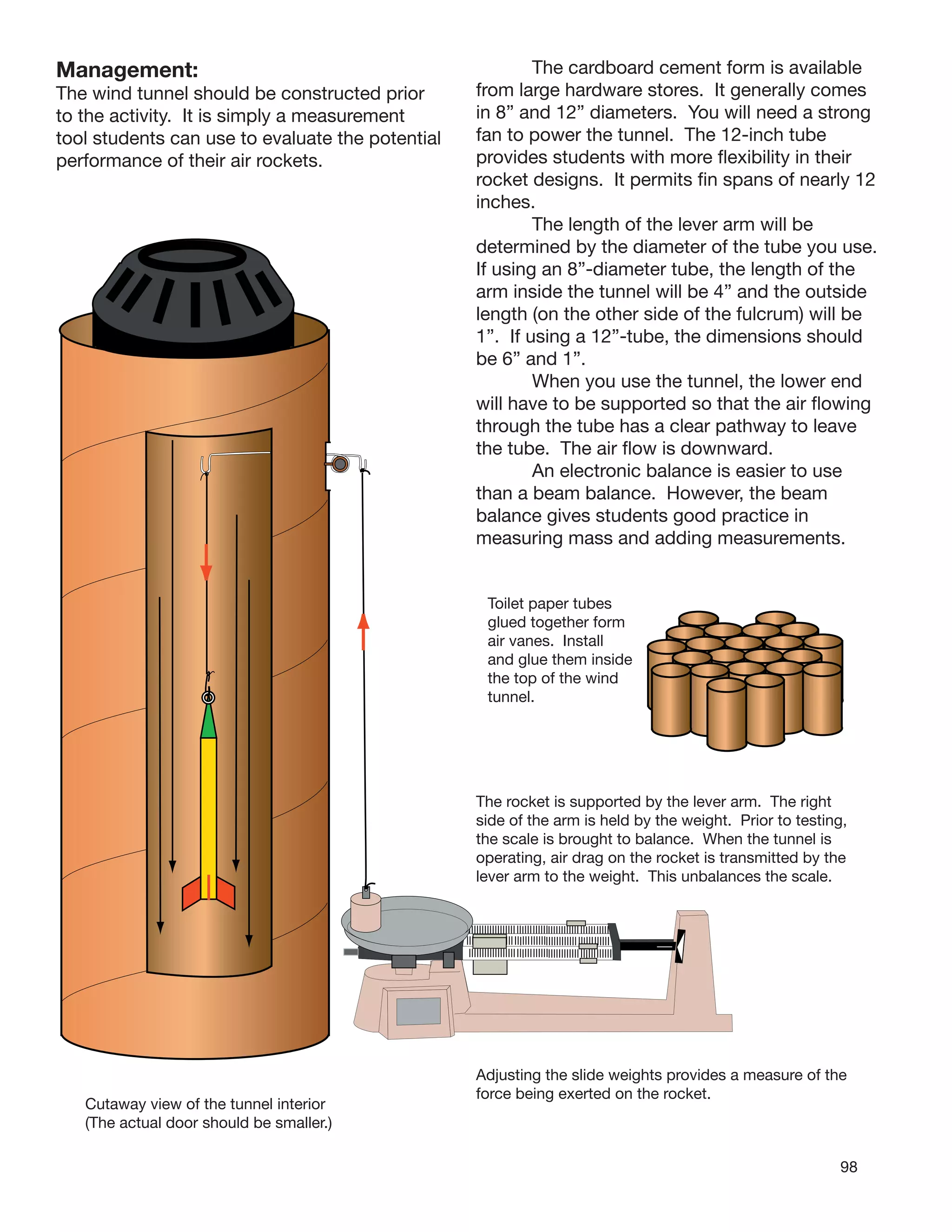

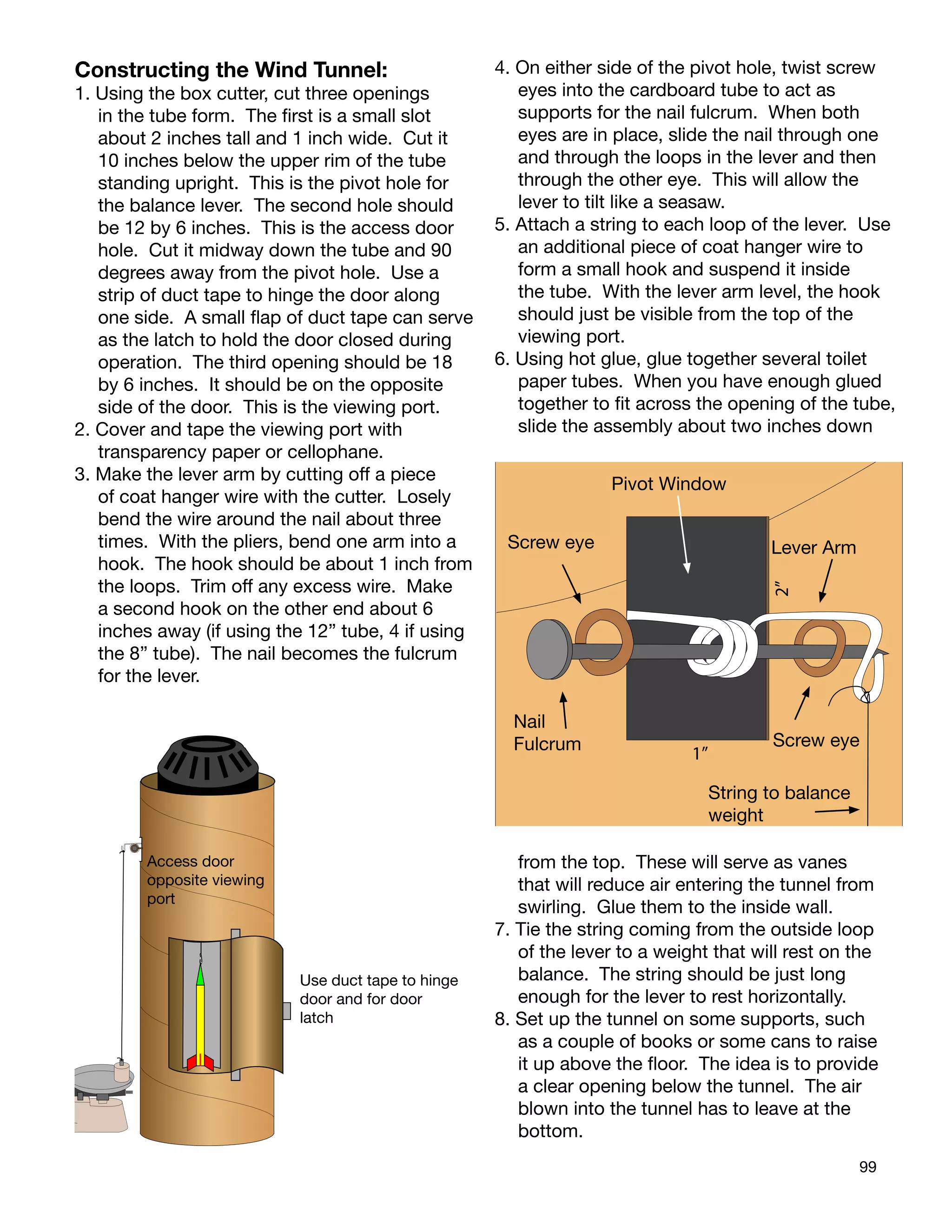

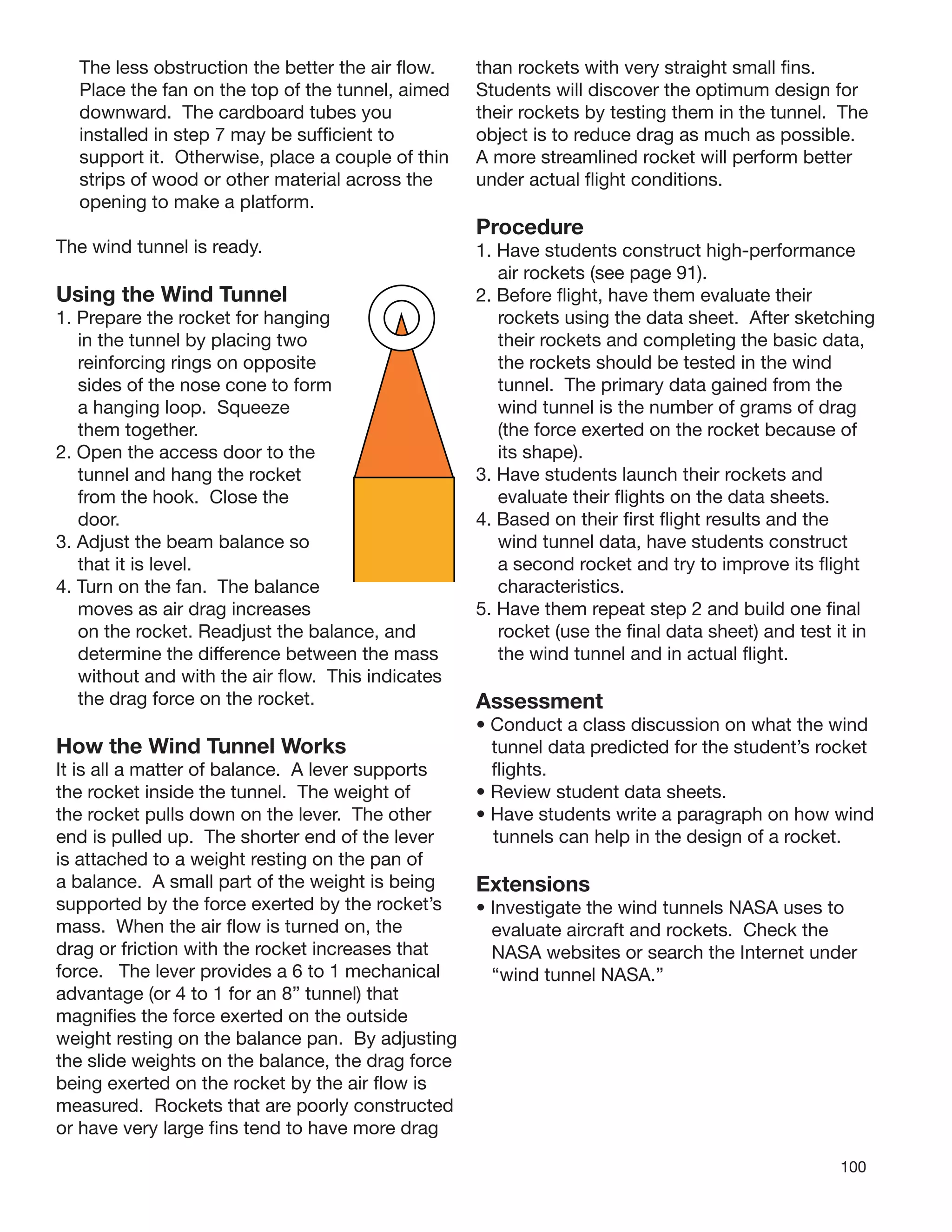

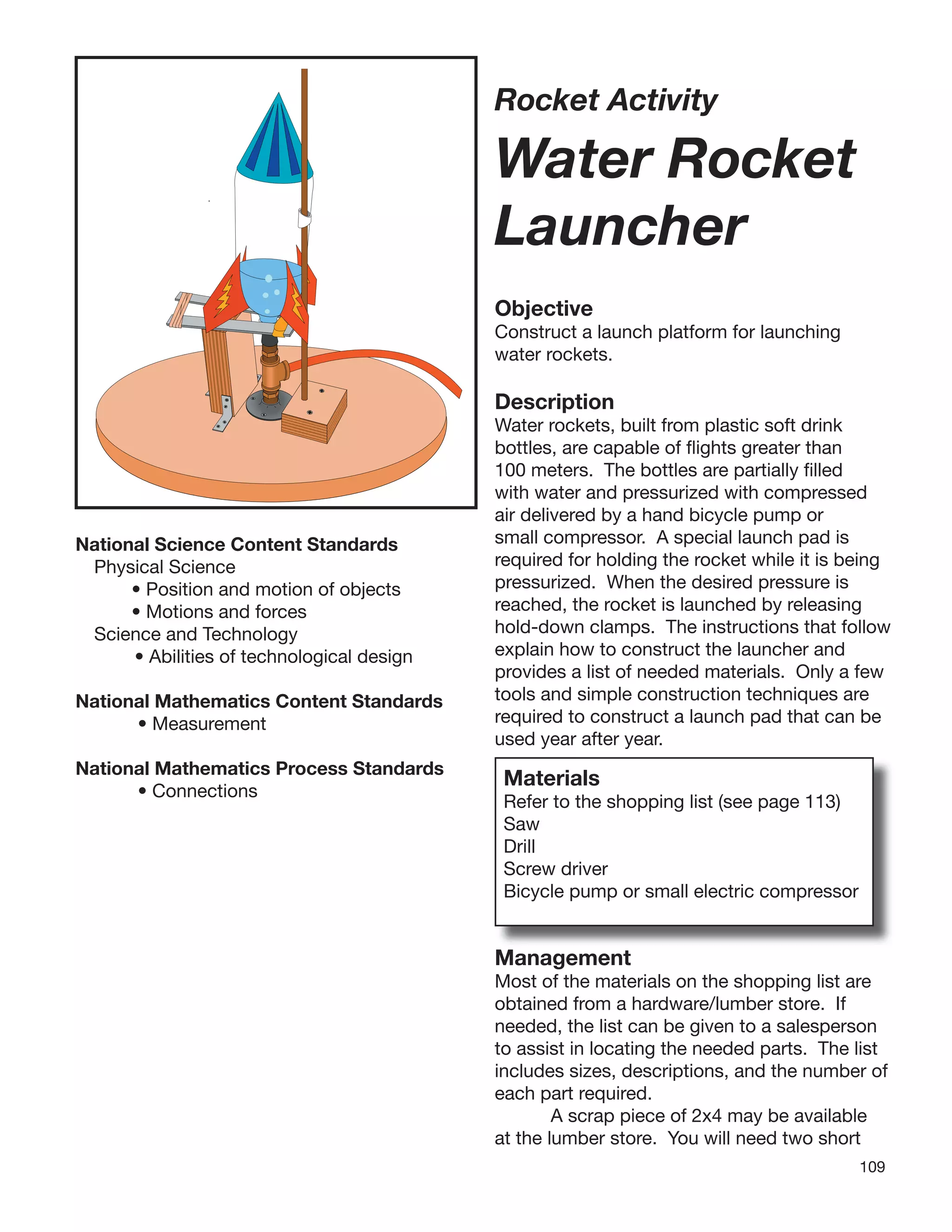

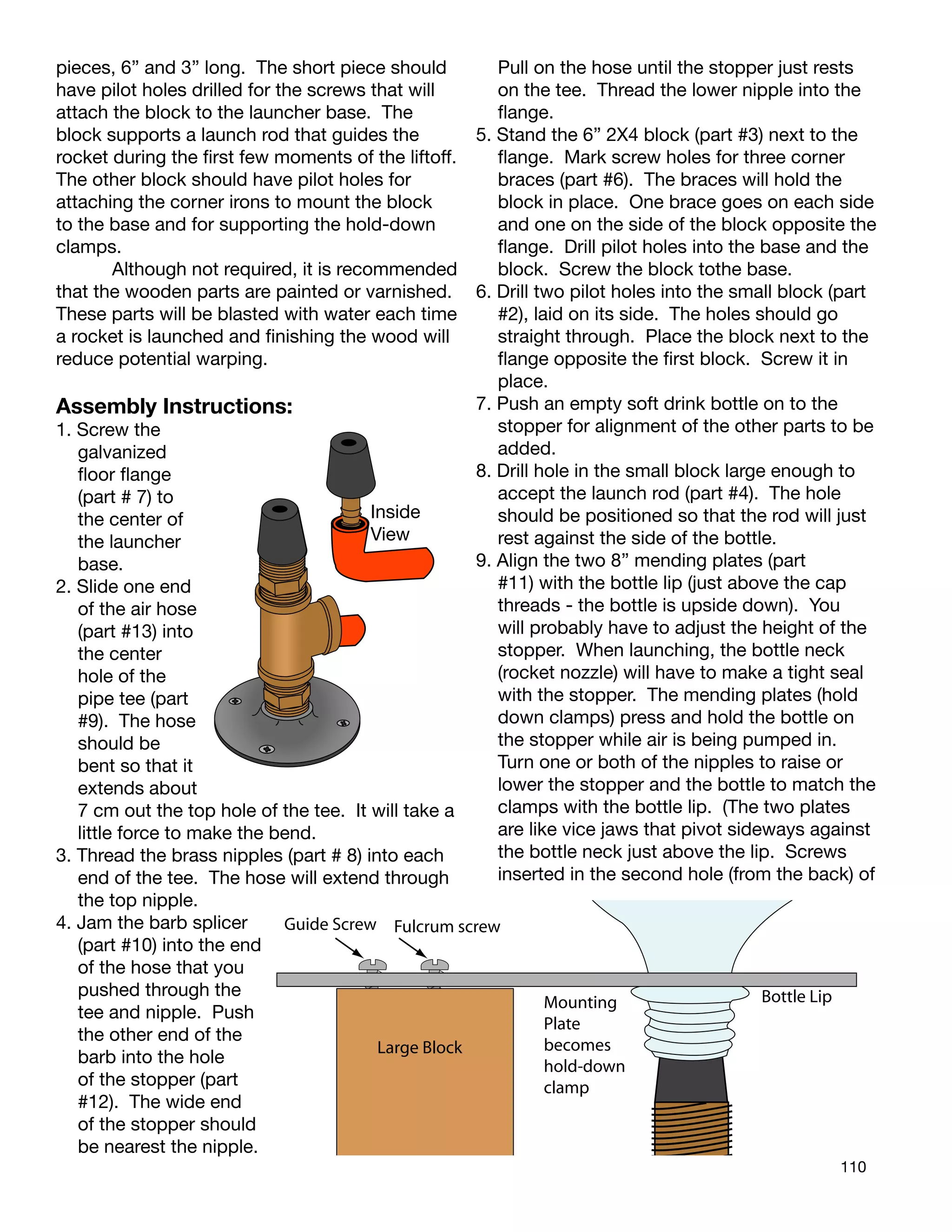

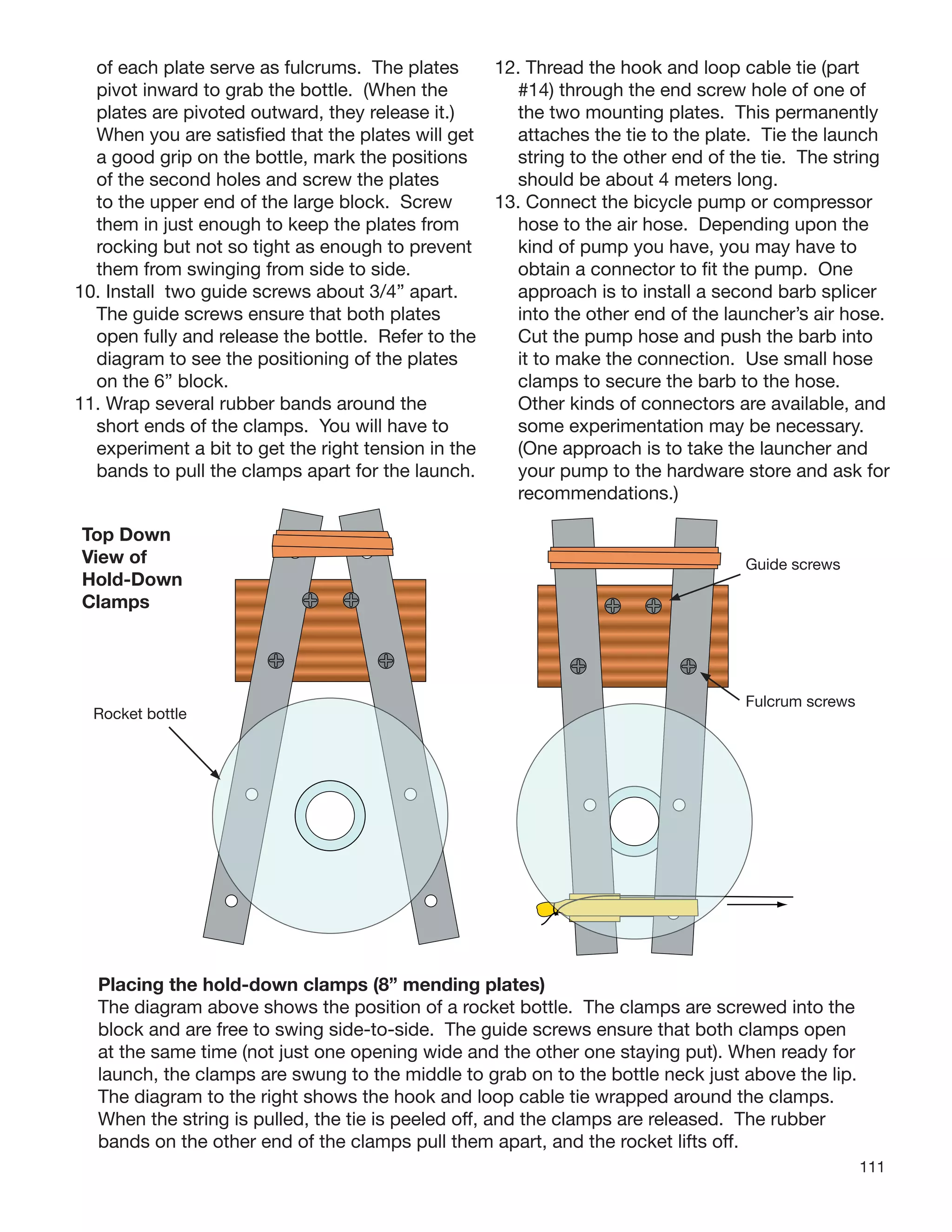

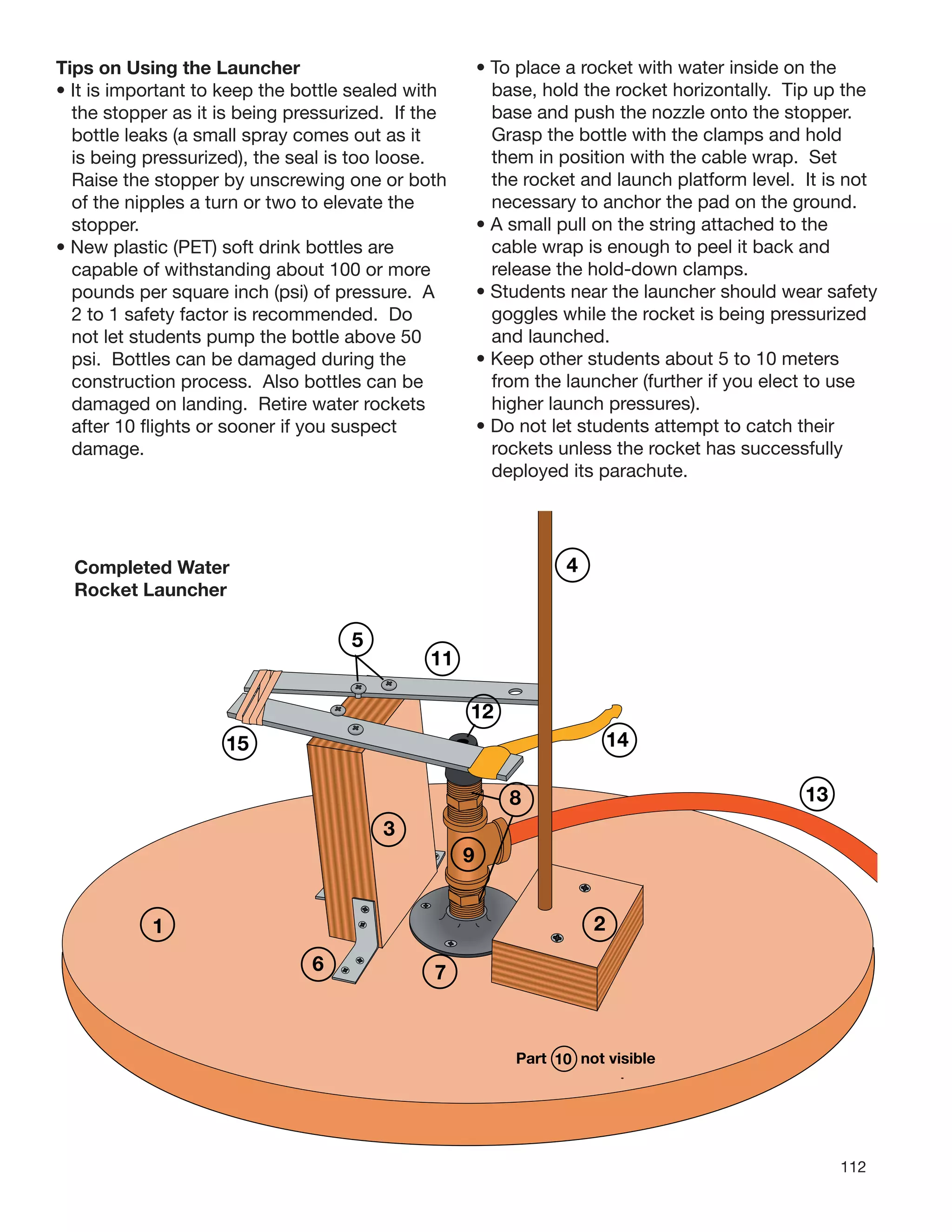

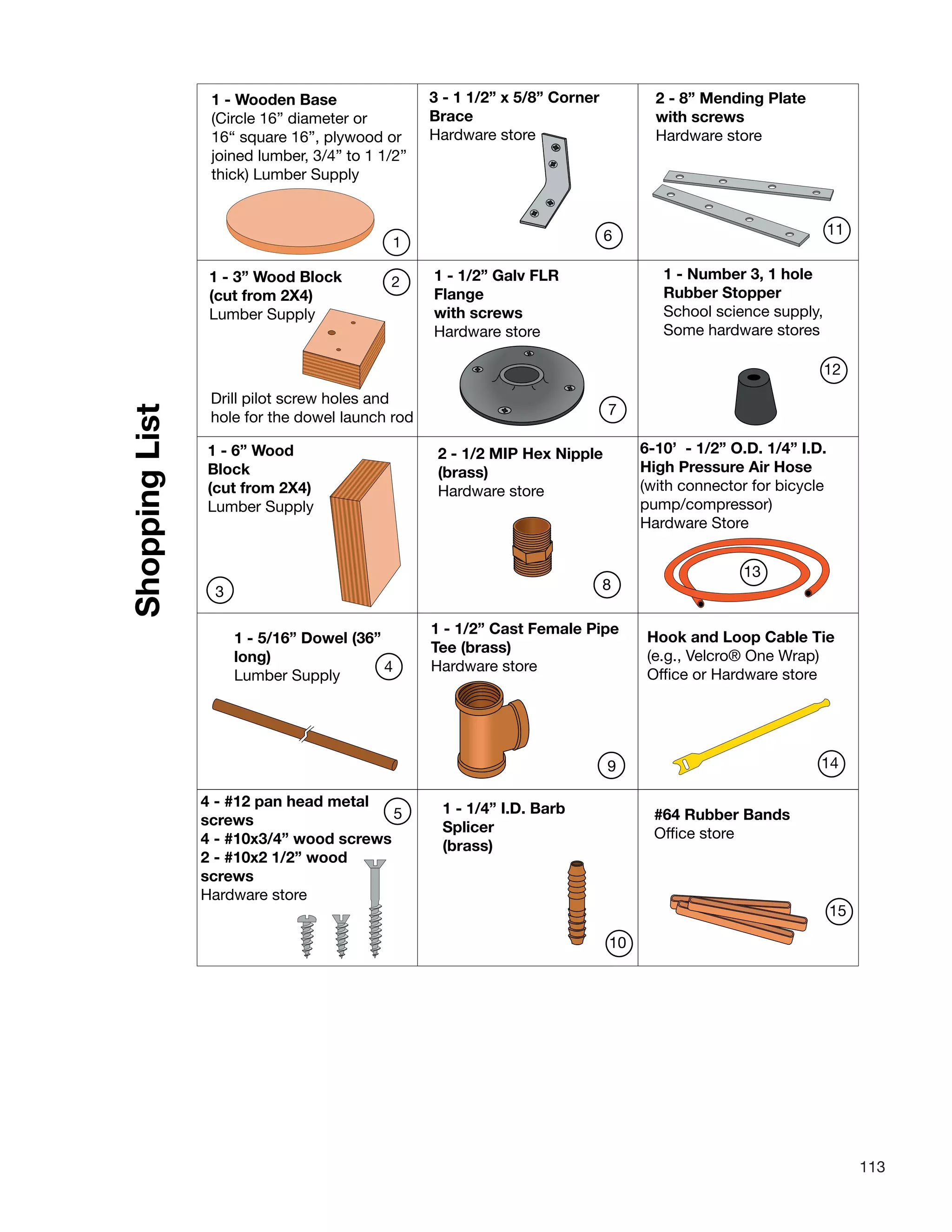

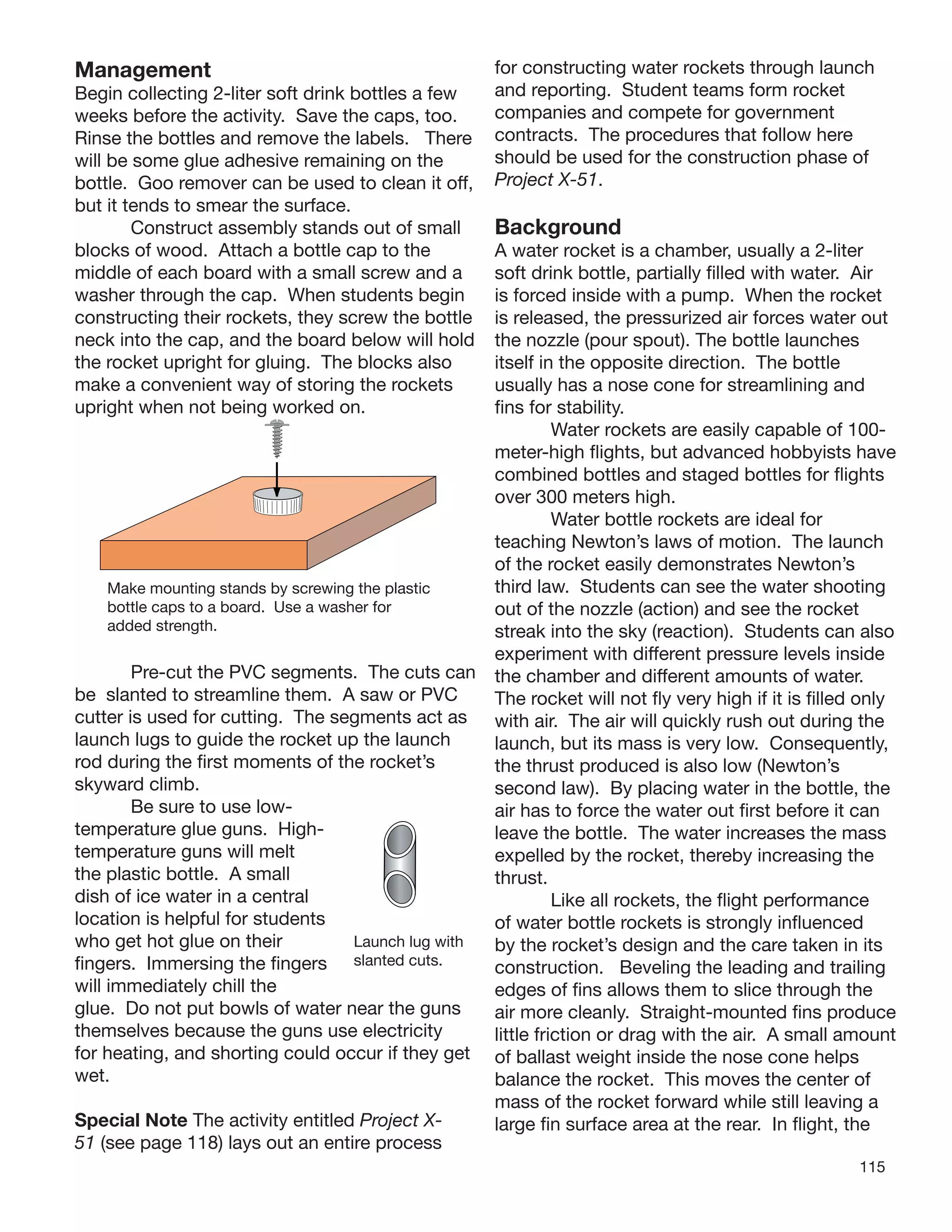

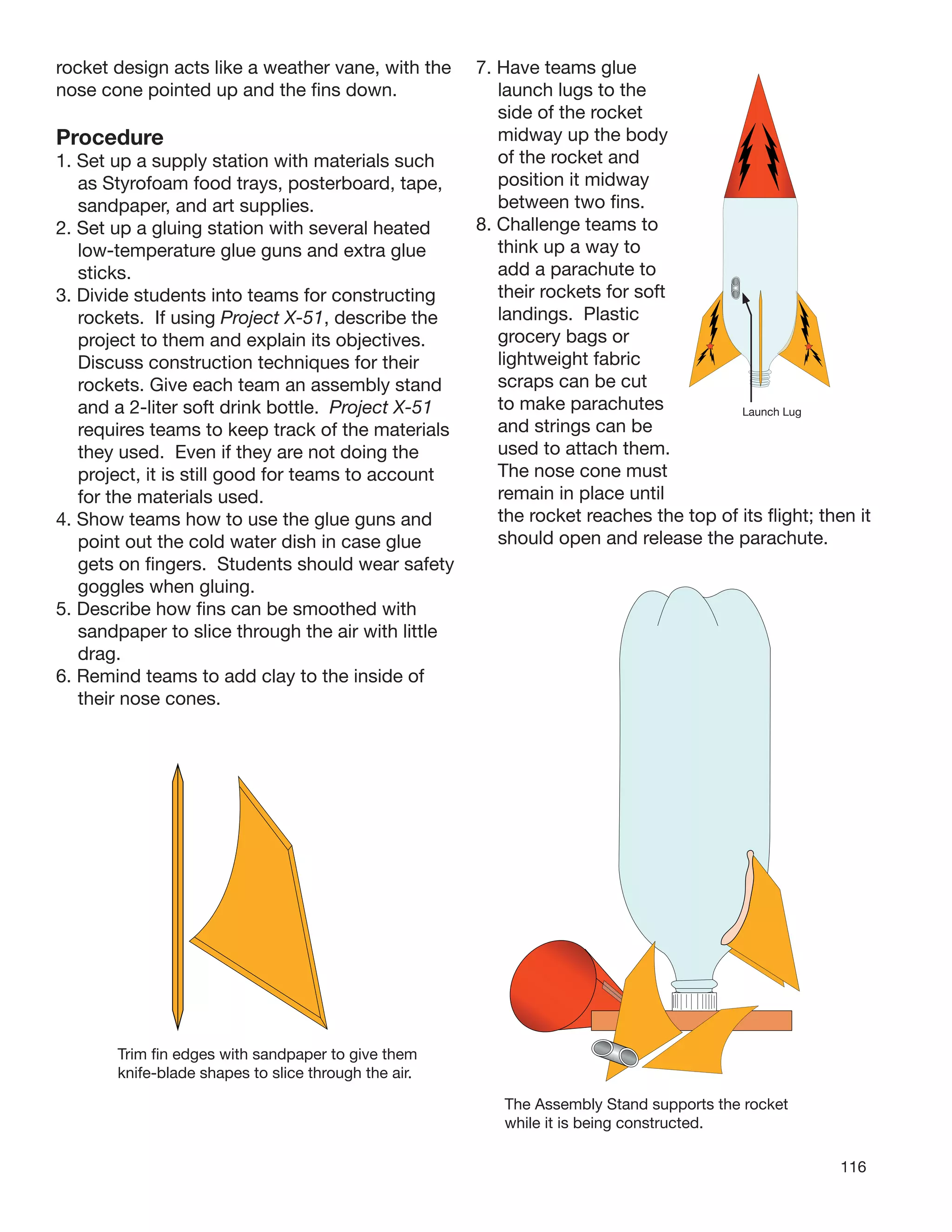

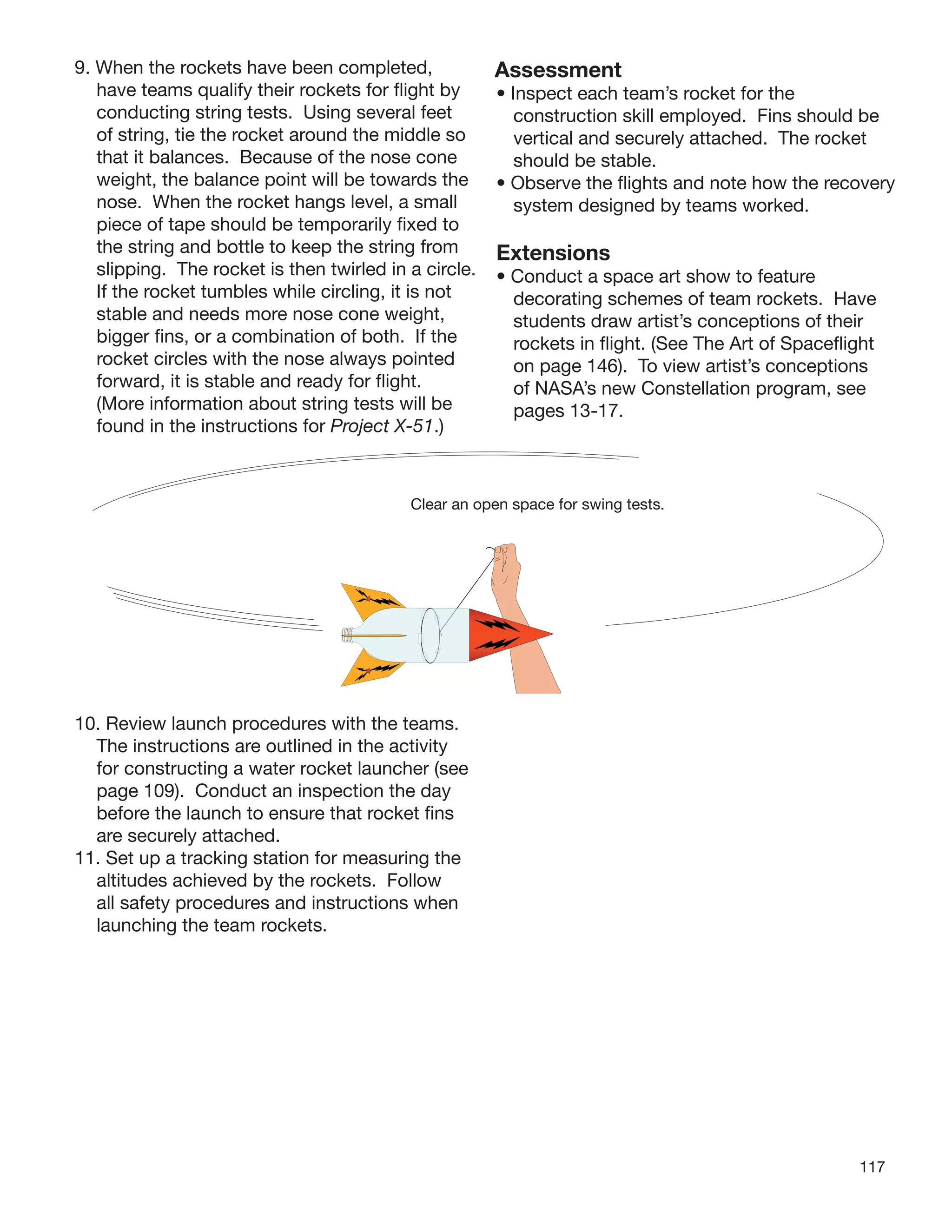

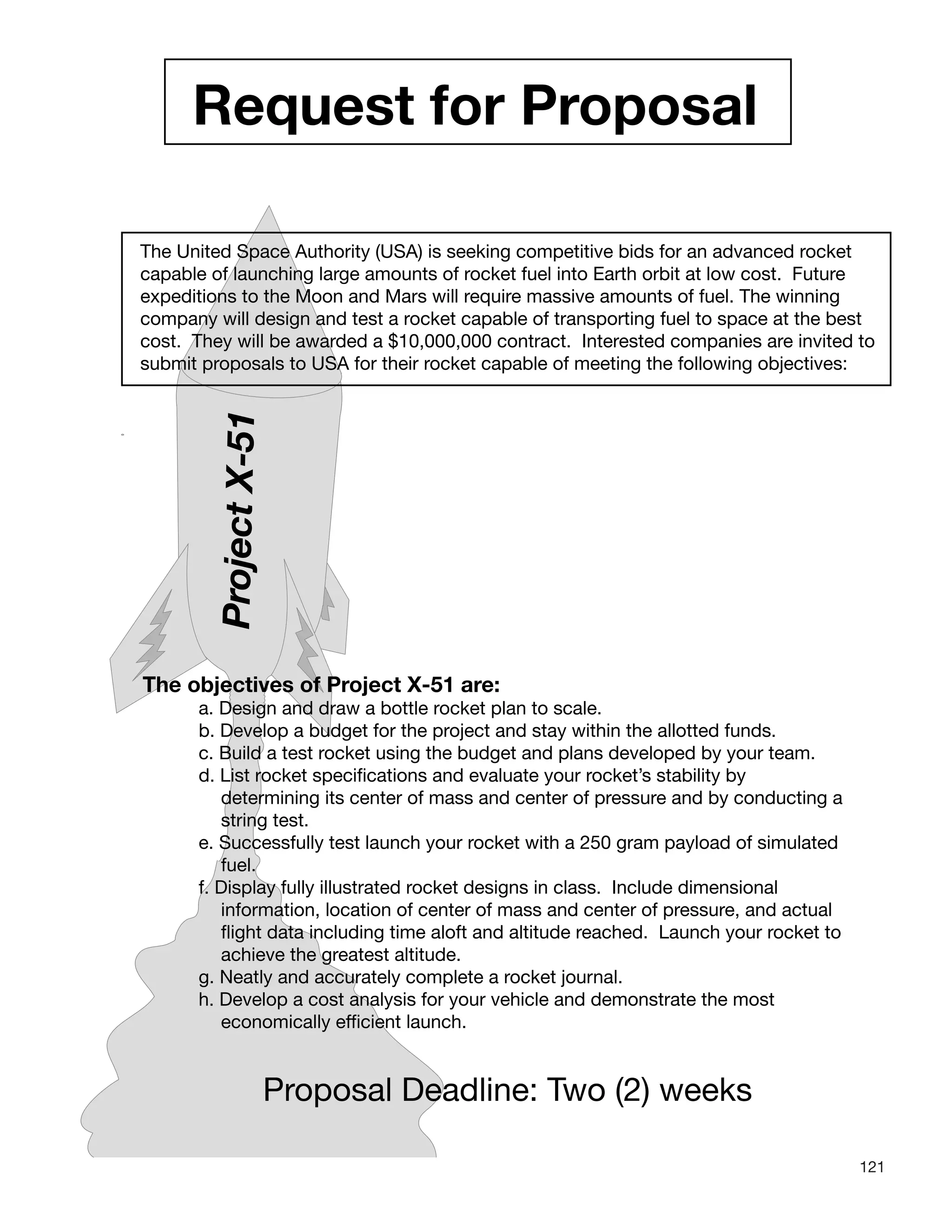

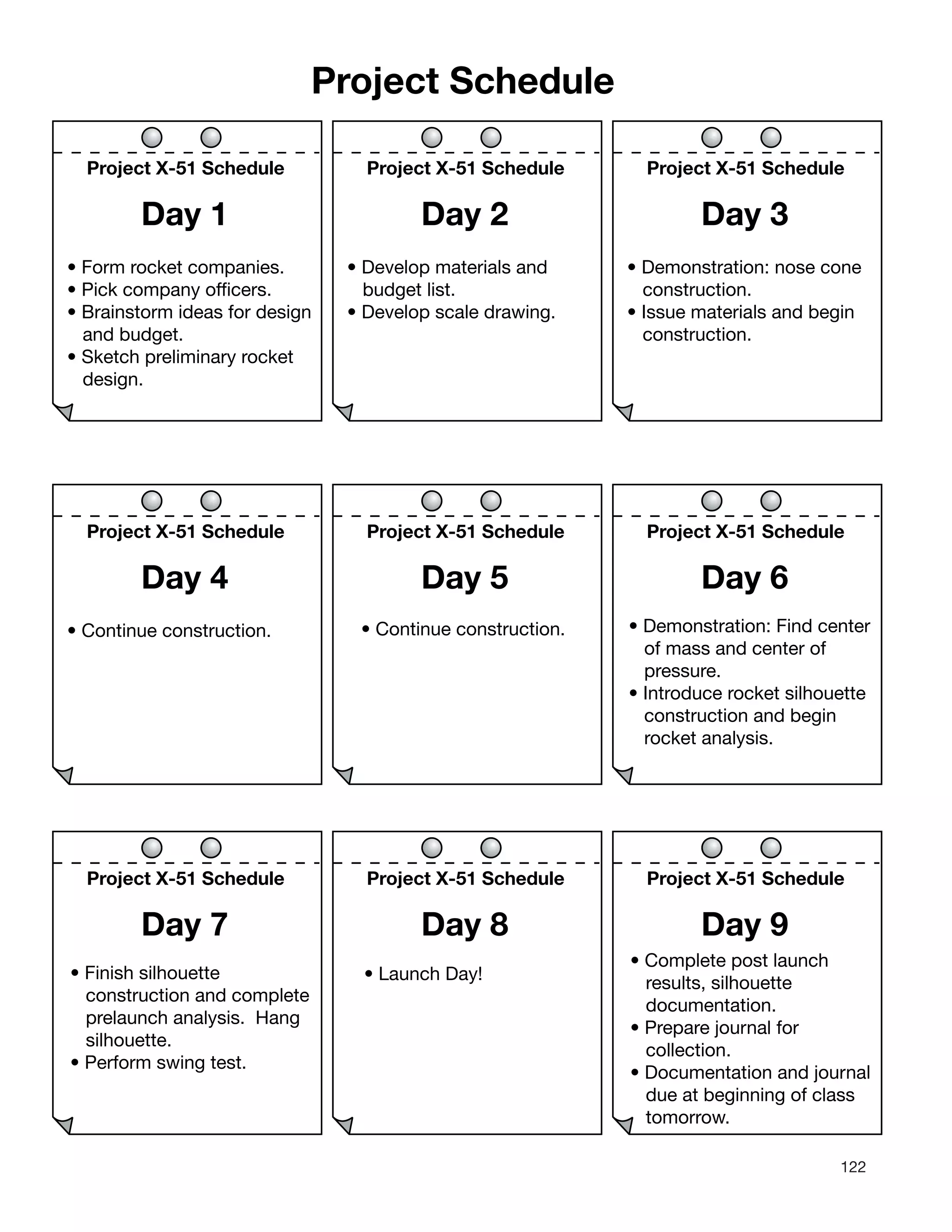

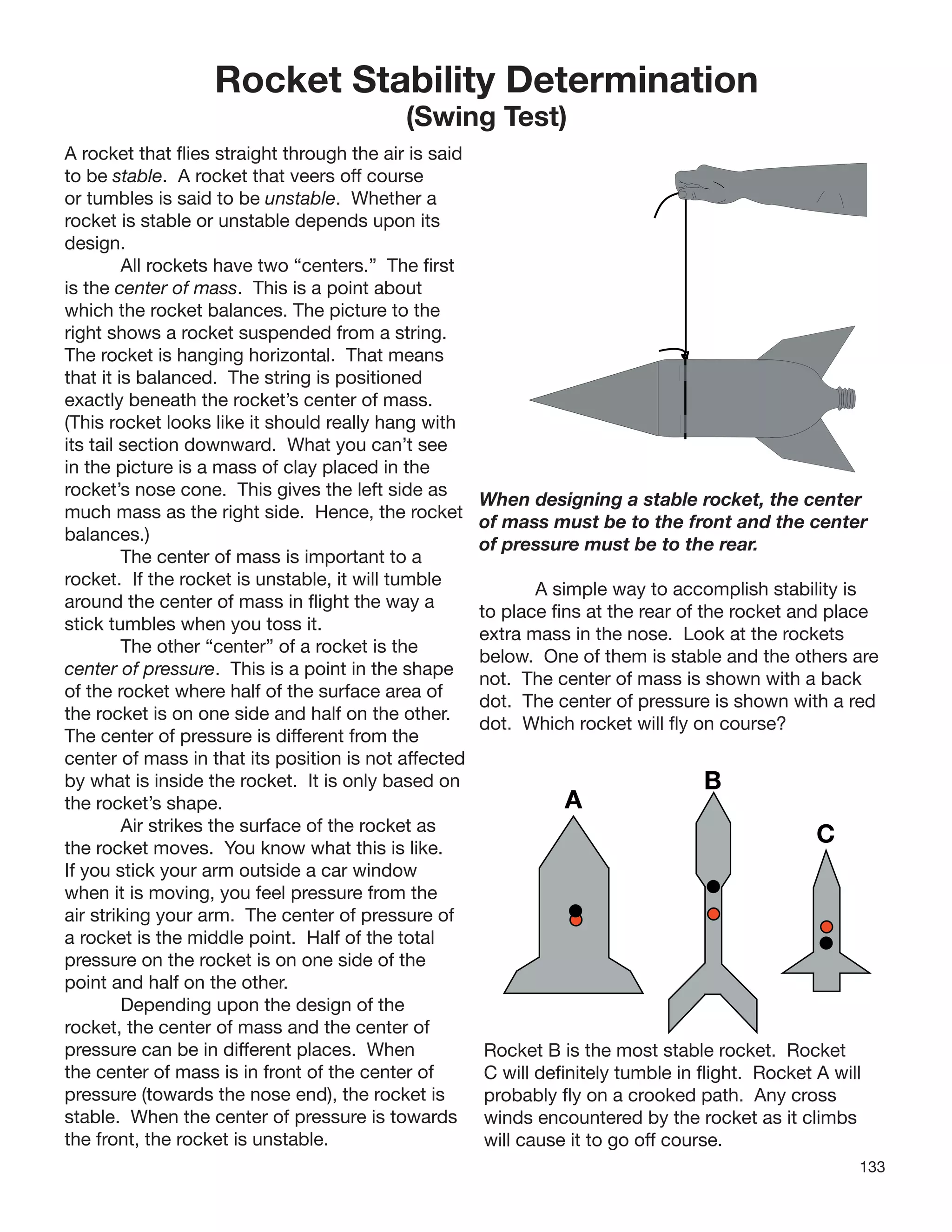

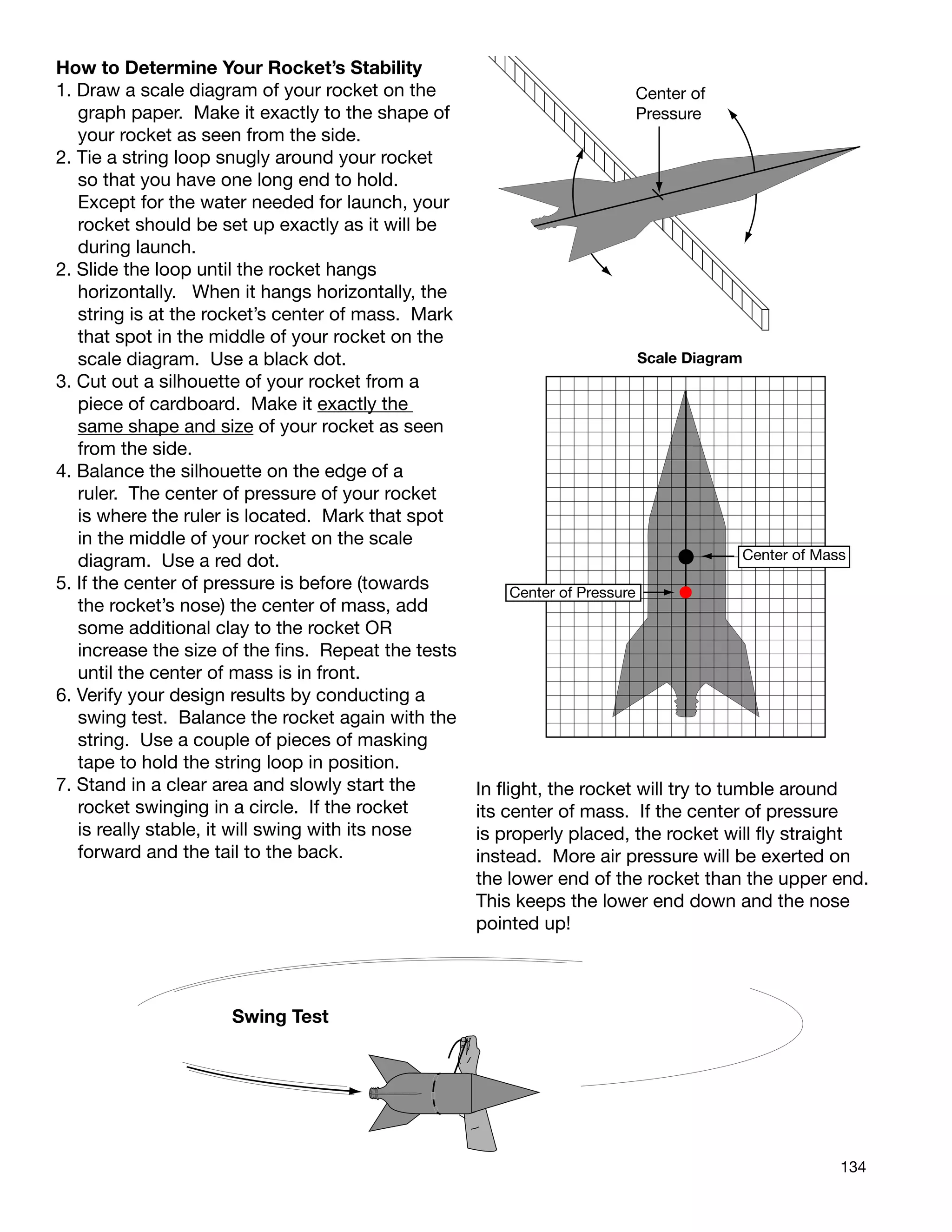

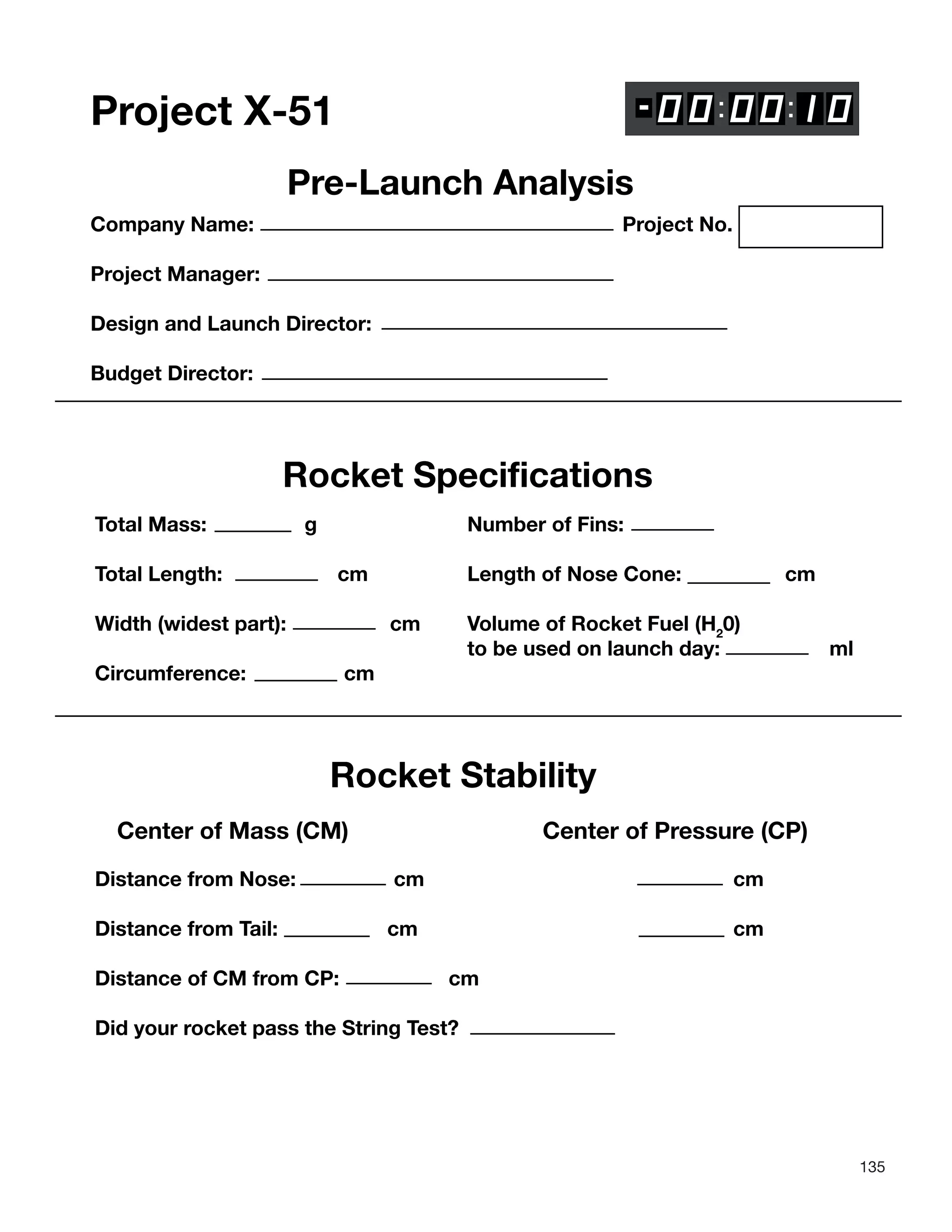

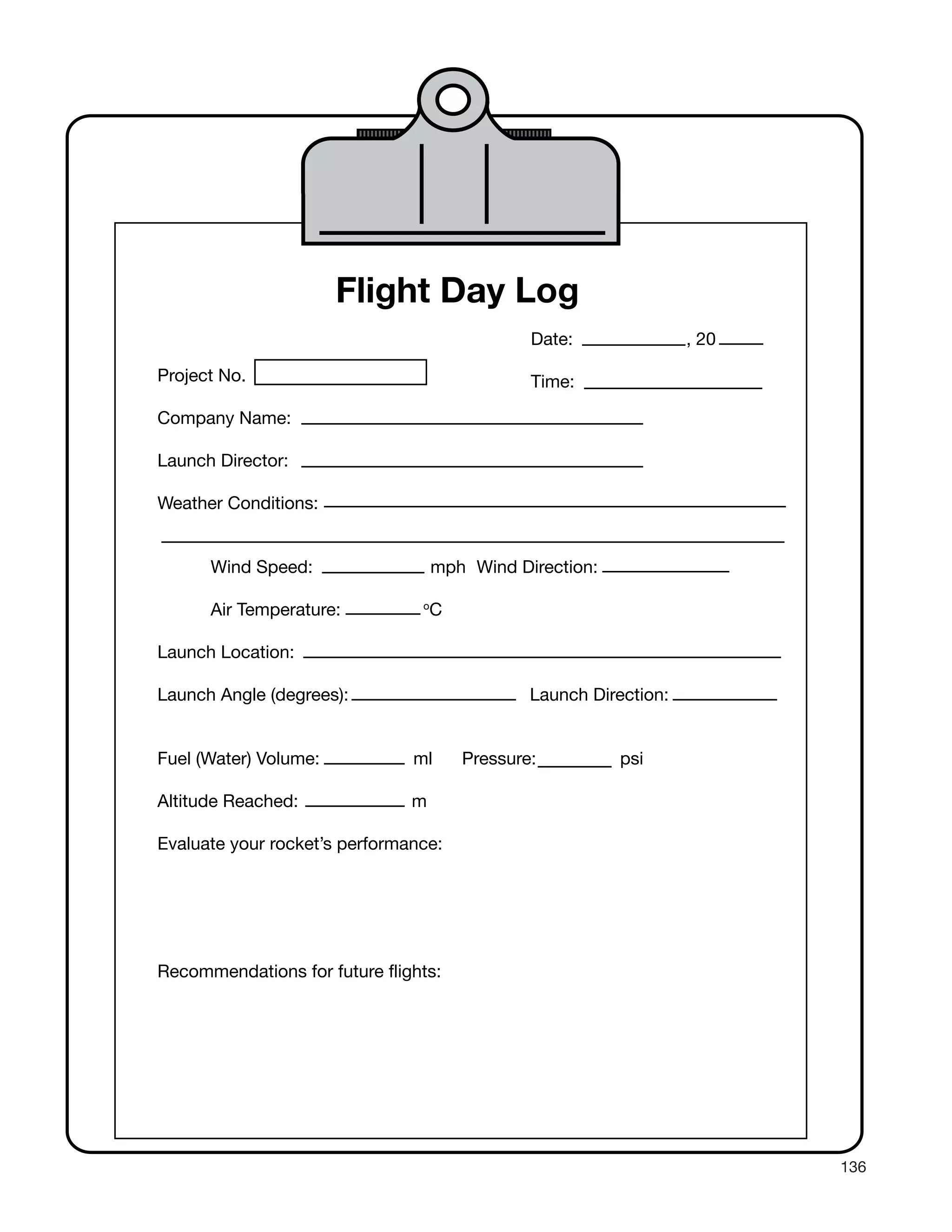

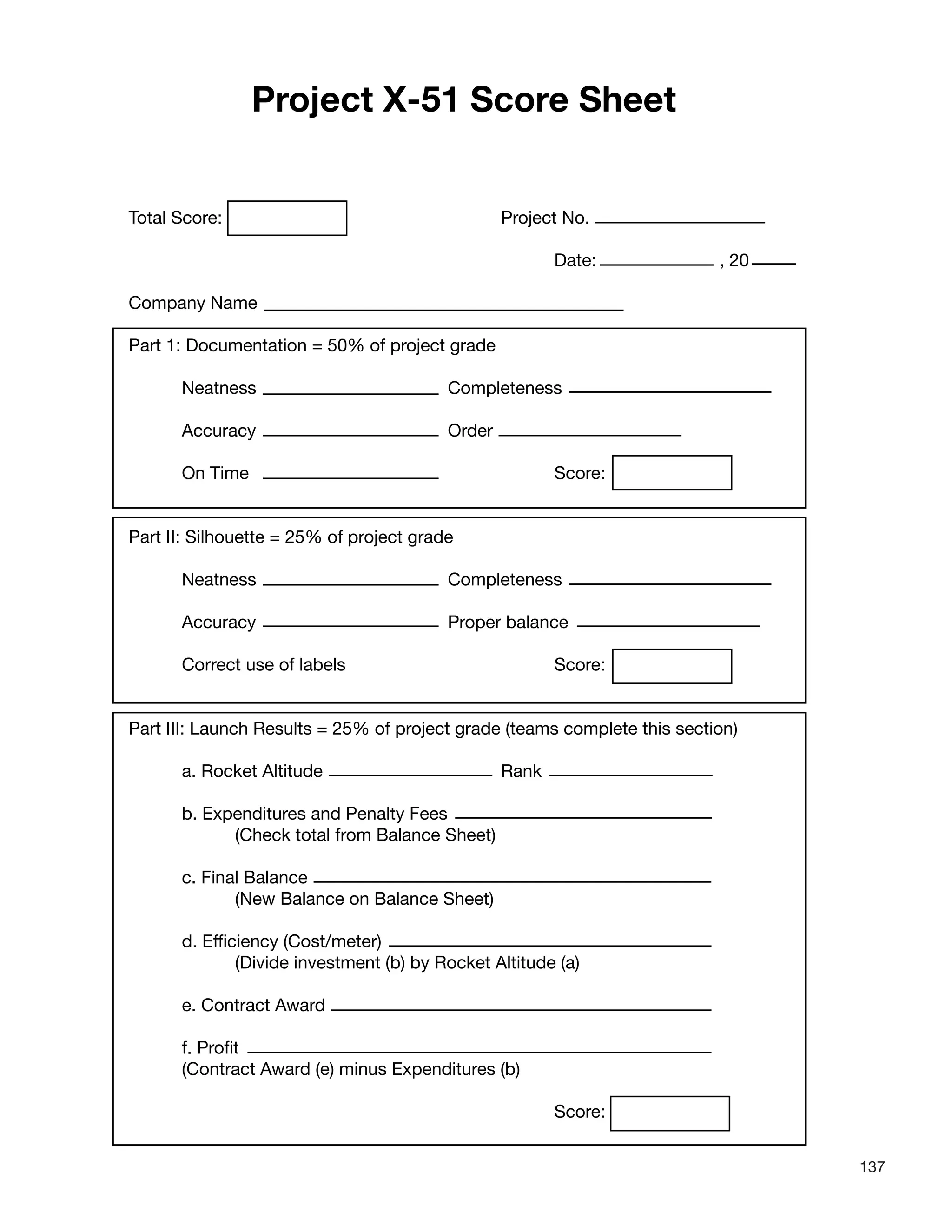

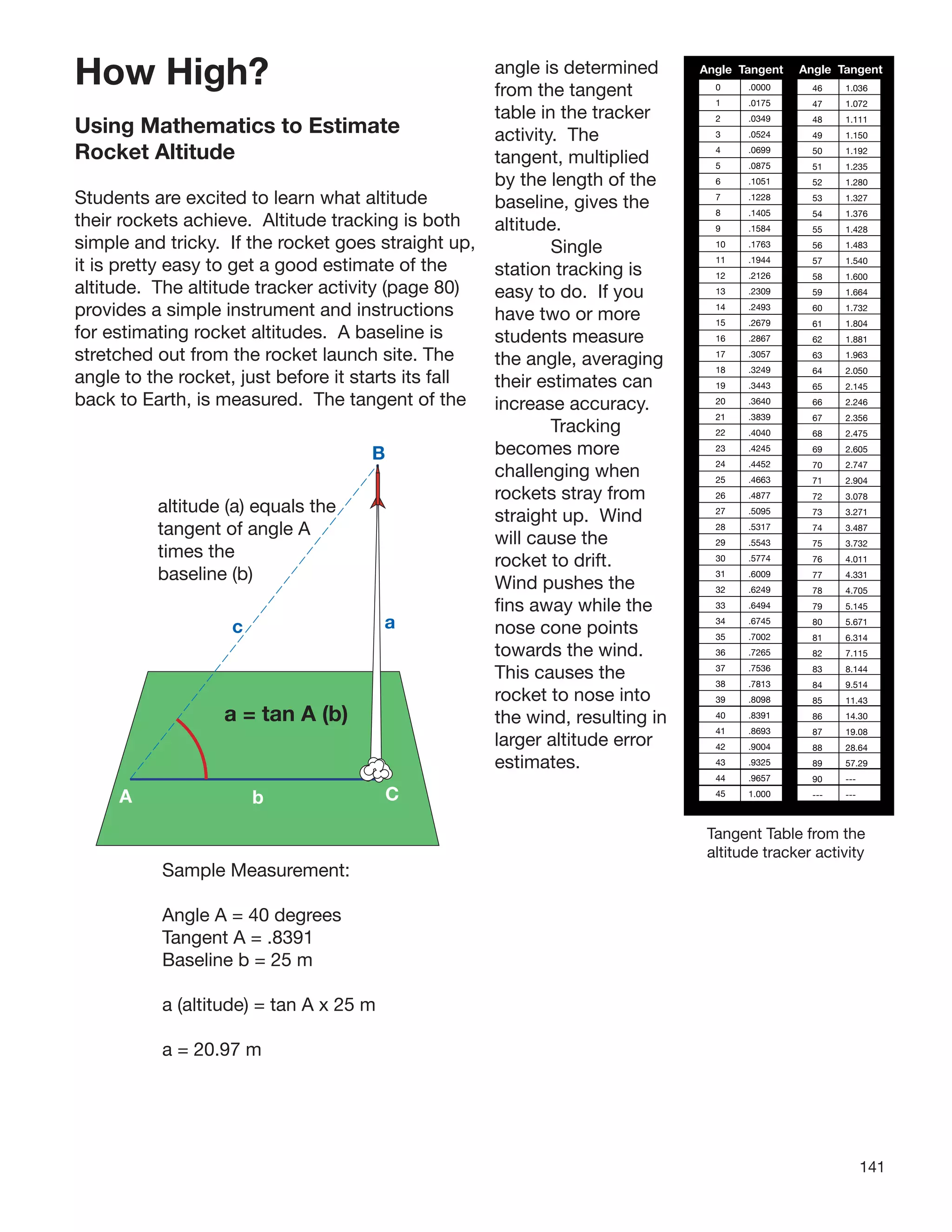

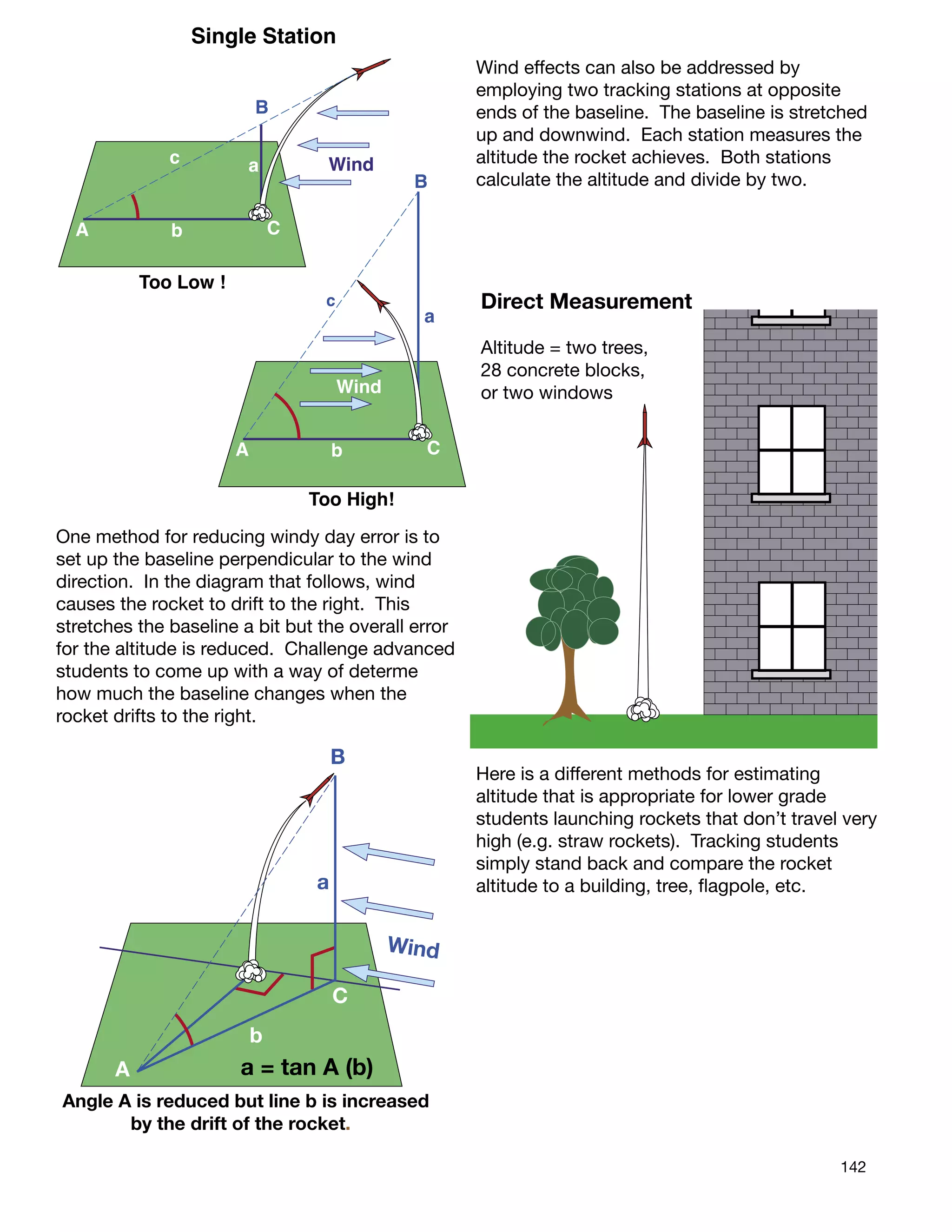

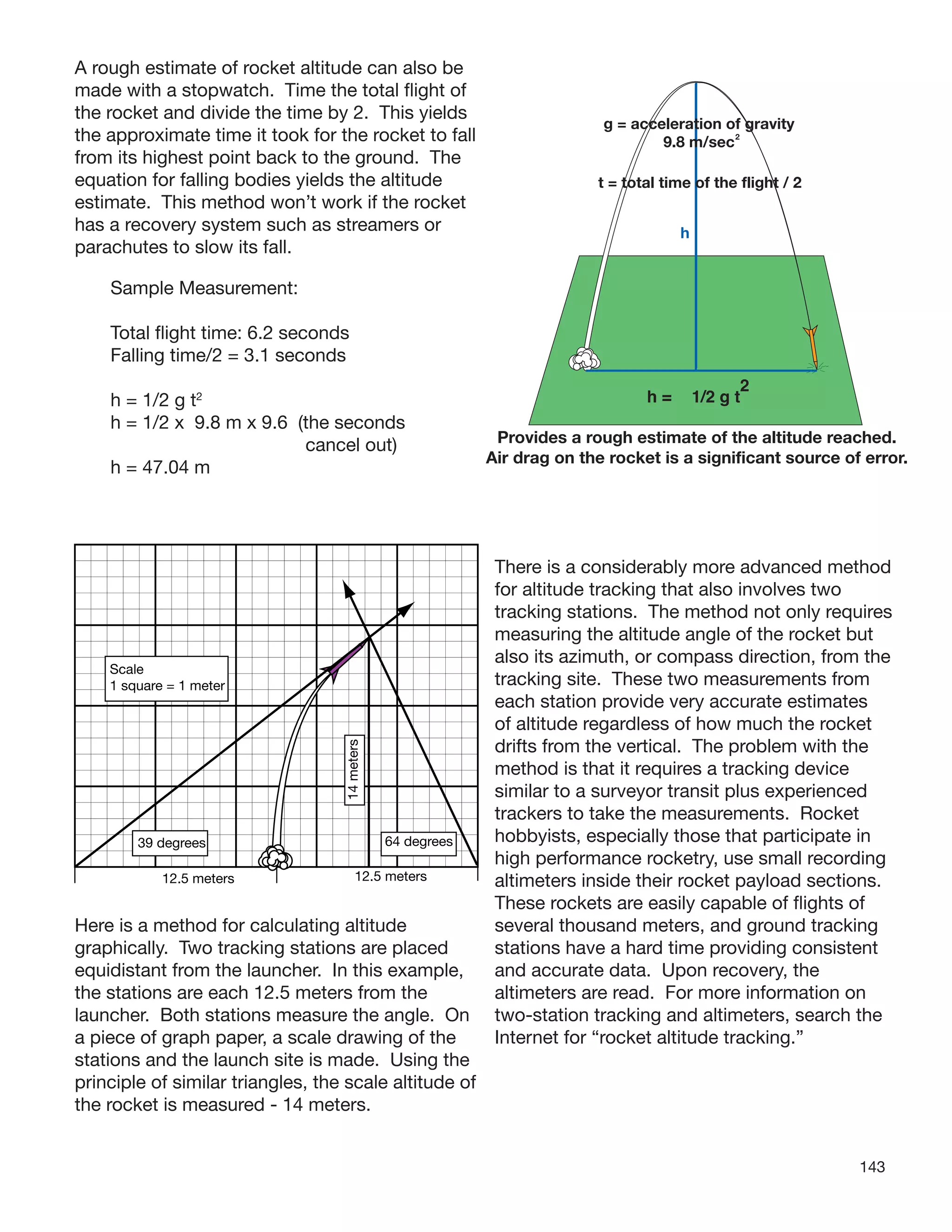

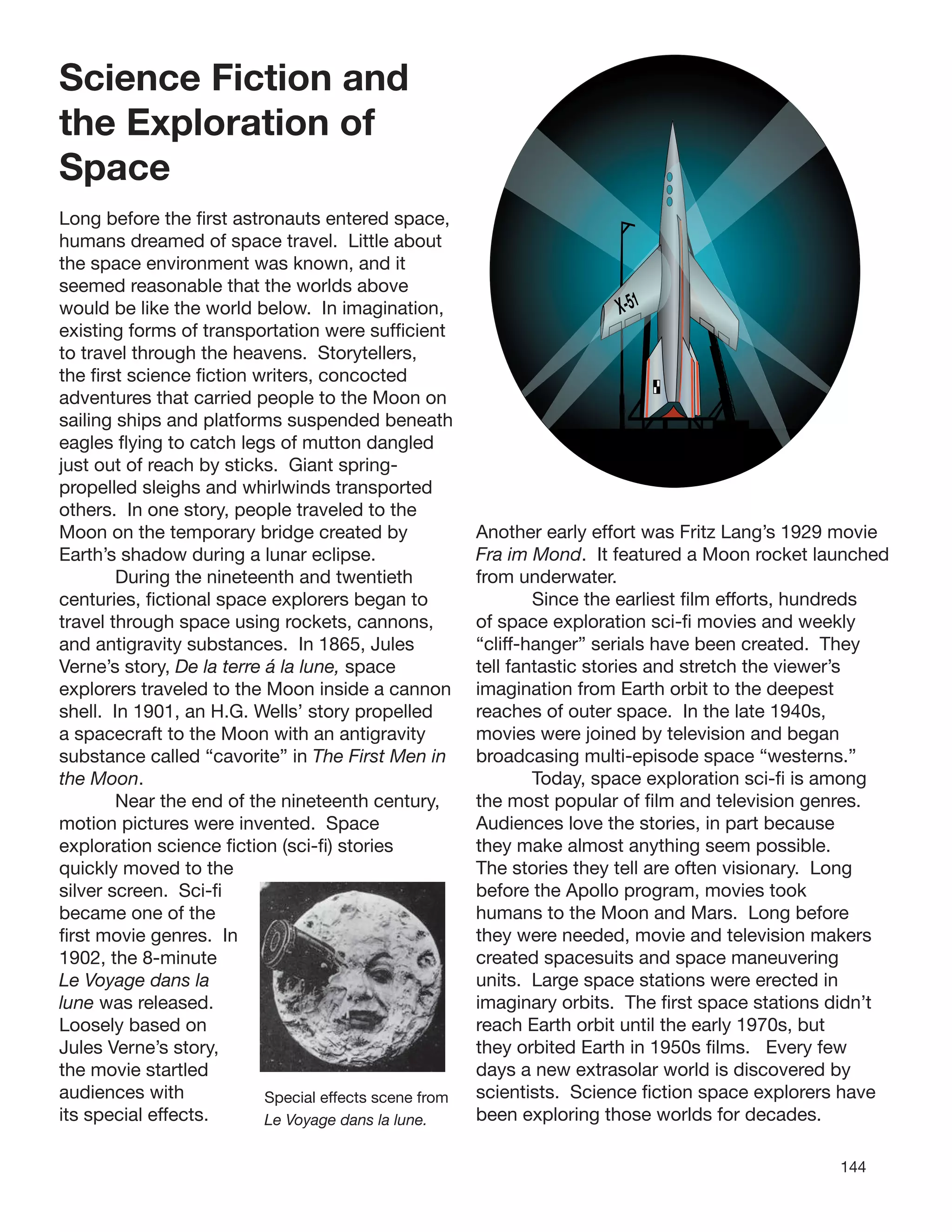

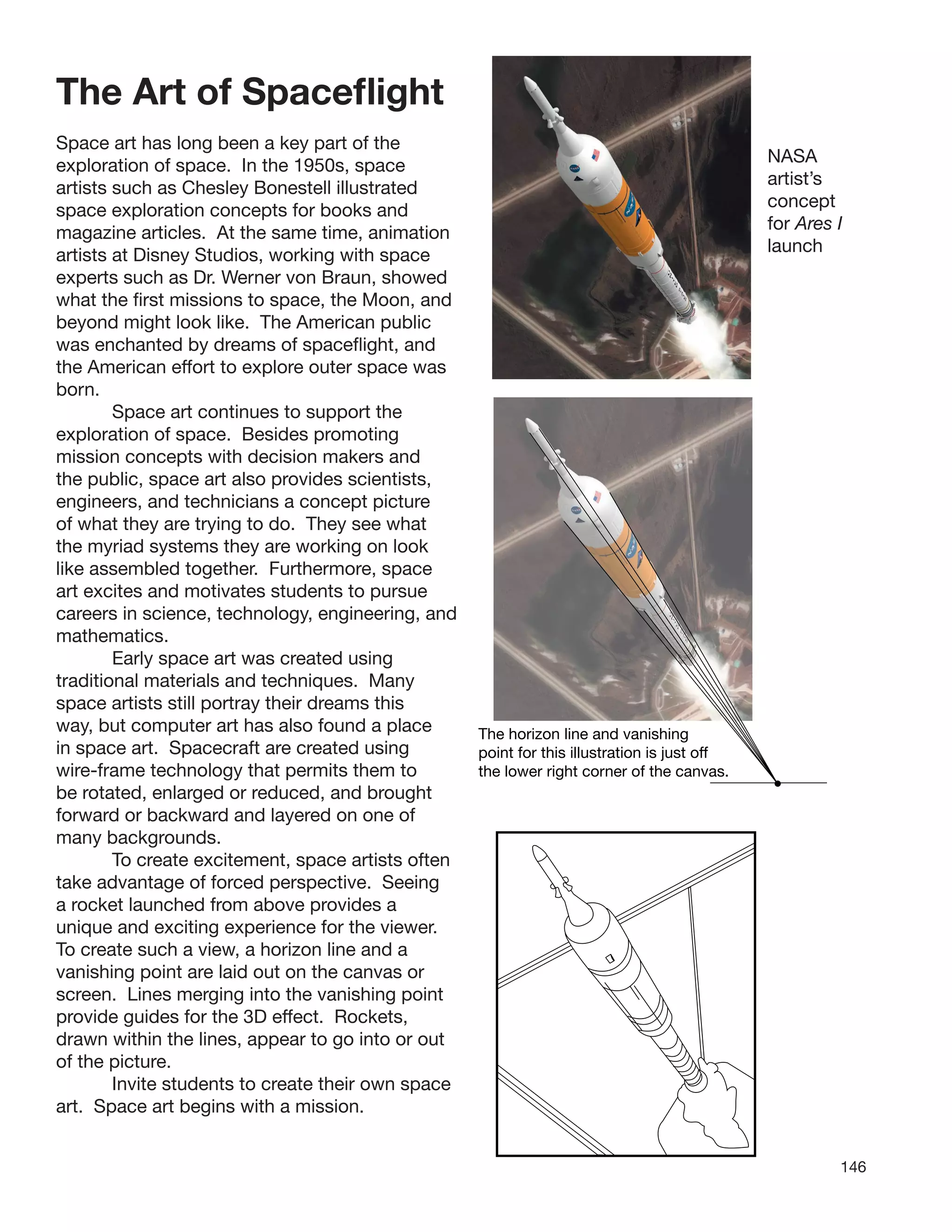

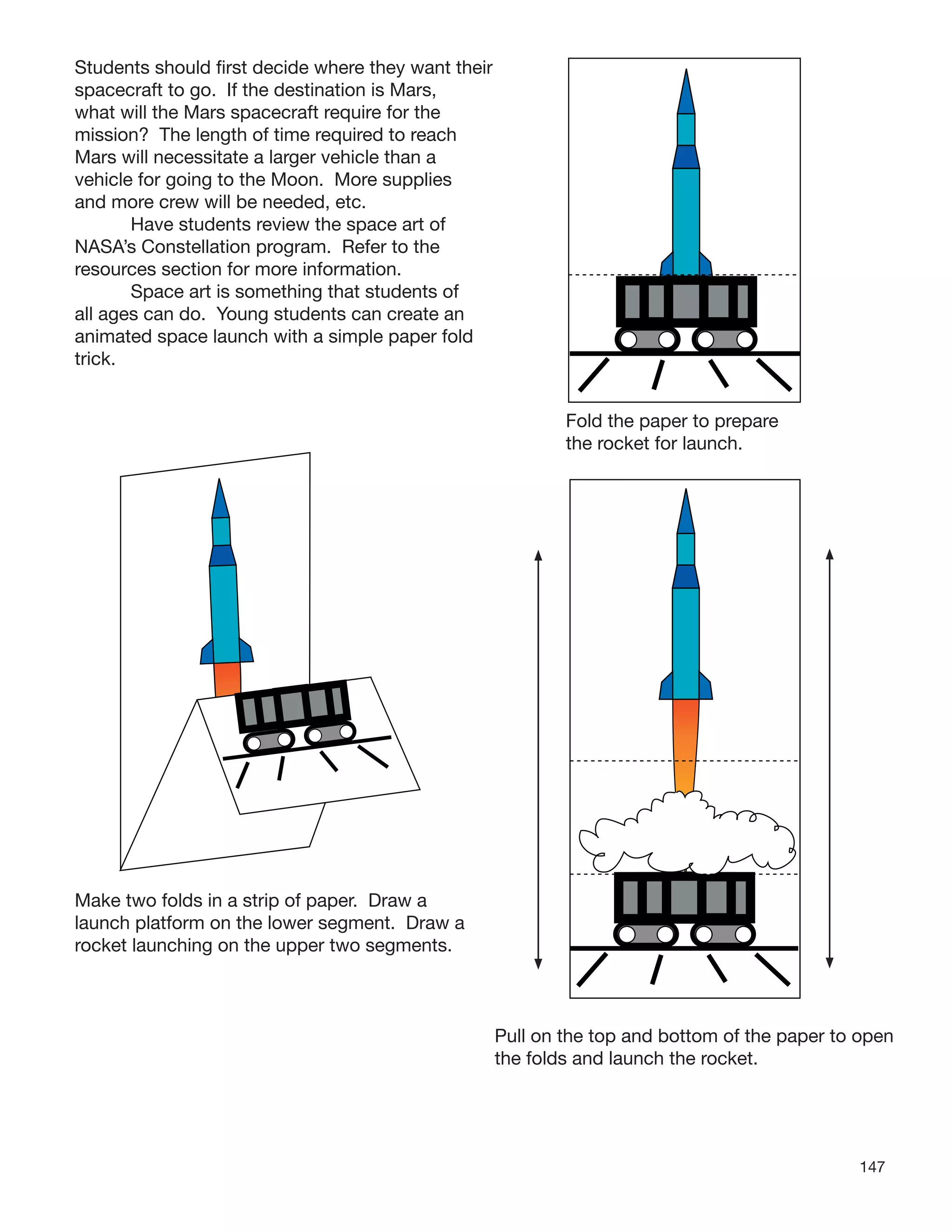

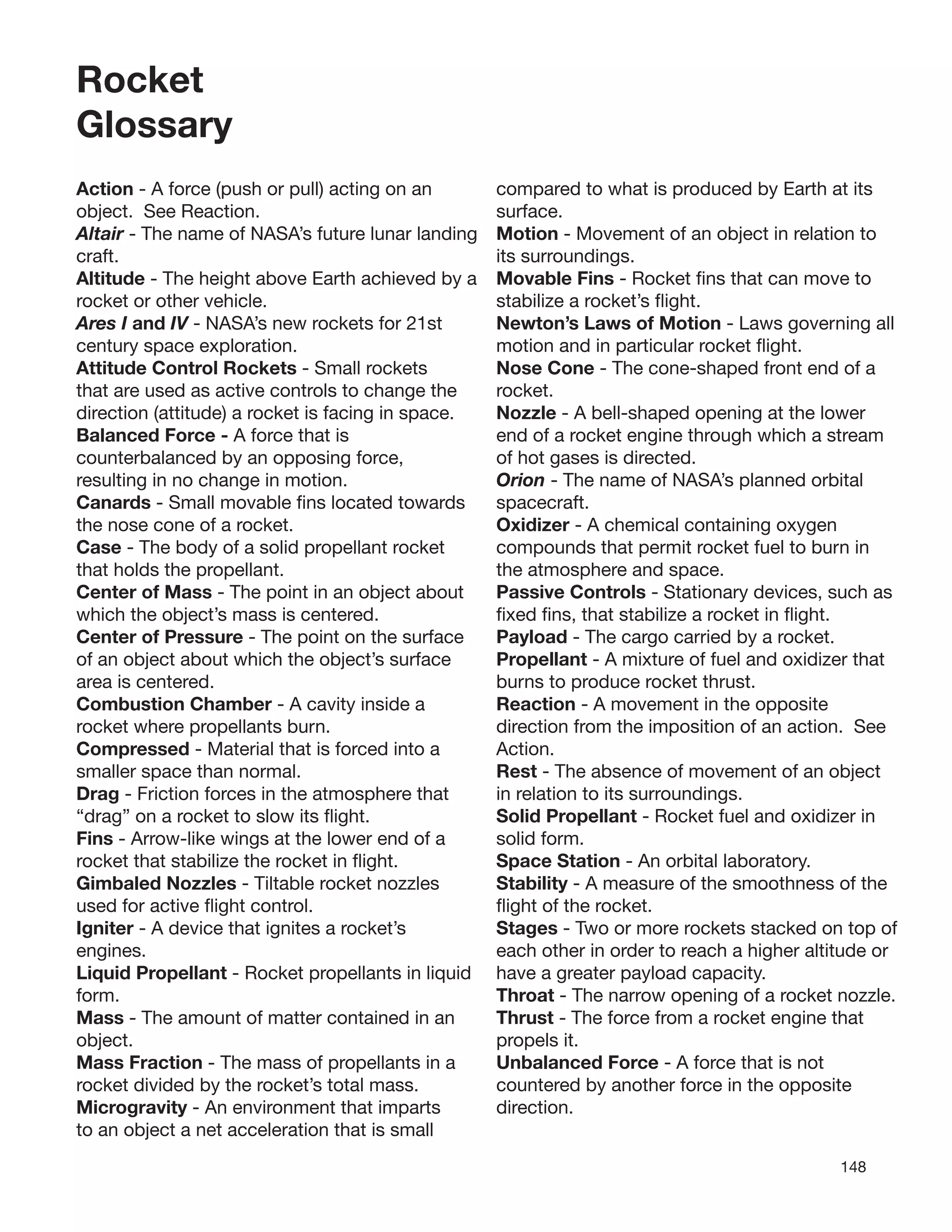

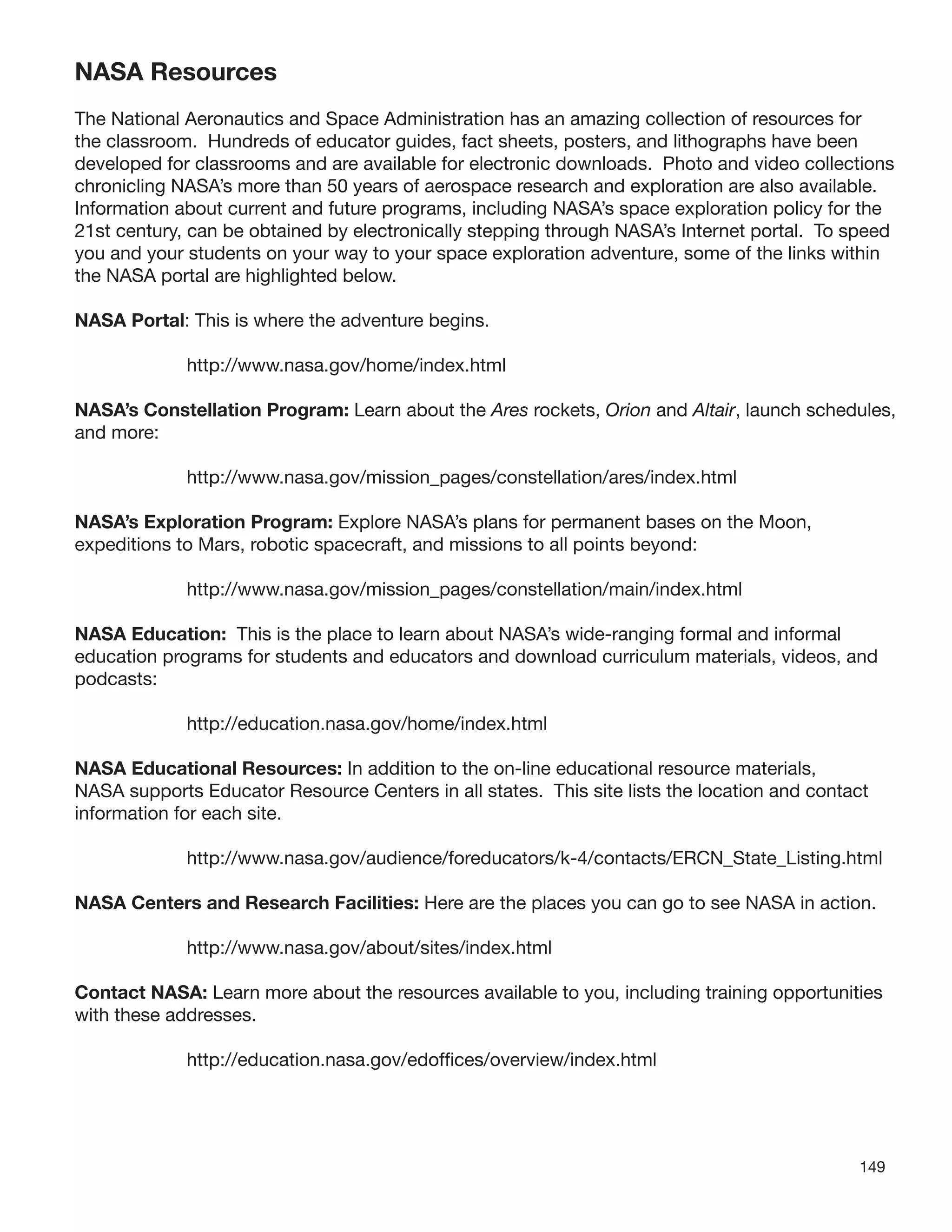

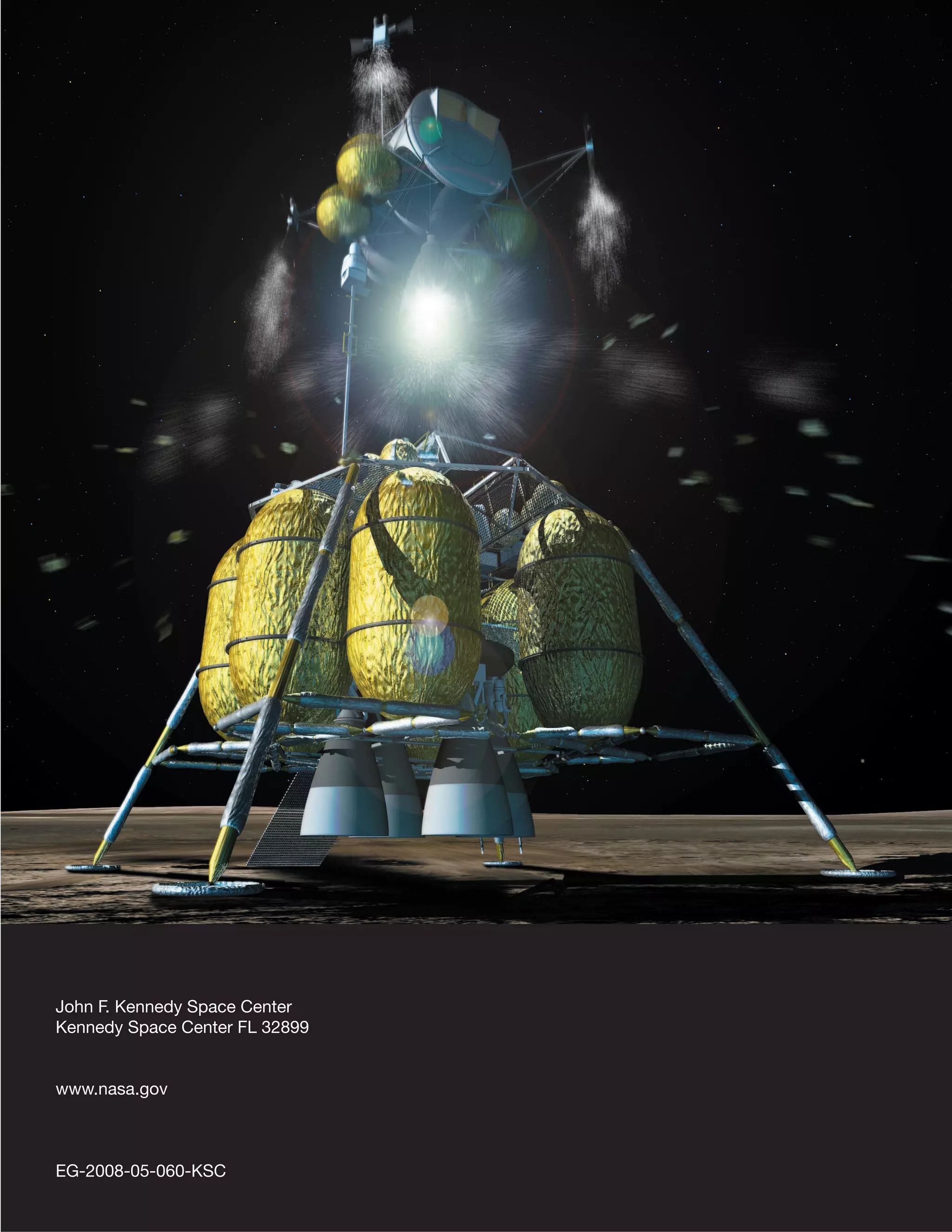

The document is an educator's guide by NASA focused on teaching students about rockets through dynamic activities that align with education standards in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. It outlines the history of rocketry, NASA's space exploration policy, and includes hands-on activities reflecting Newton's laws of motion. The guide aims to inspire future generations in the fields of space exploration and rocket science.