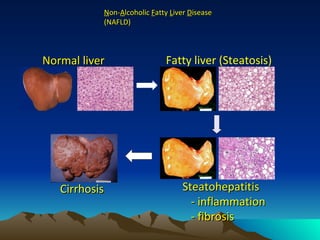

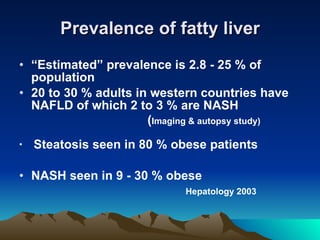

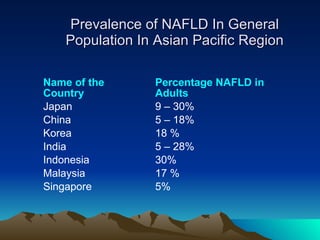

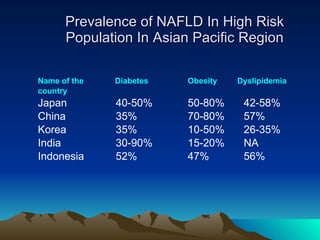

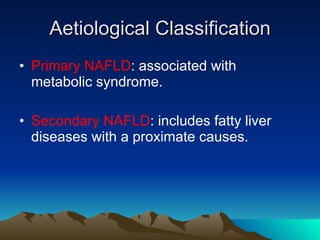

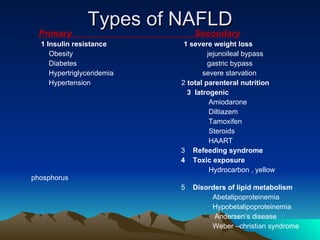

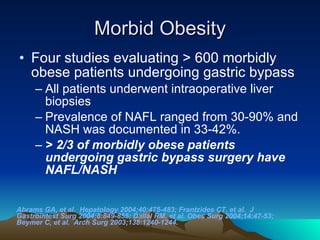

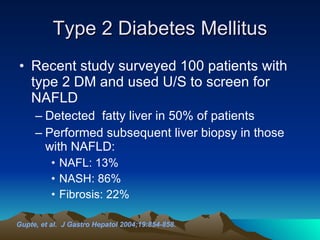

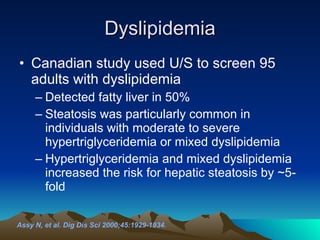

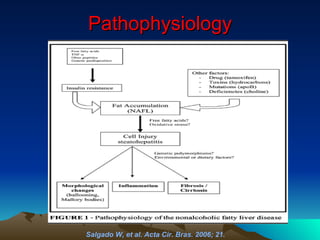

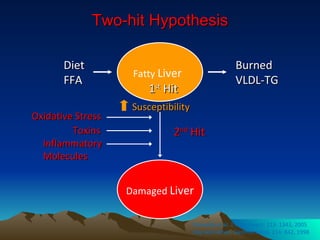

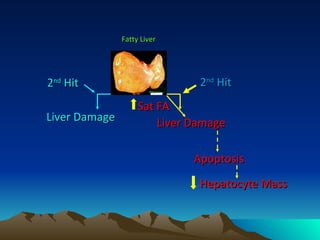

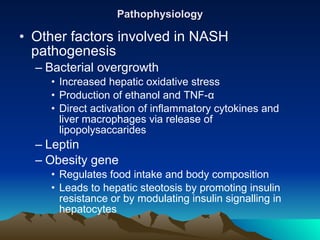

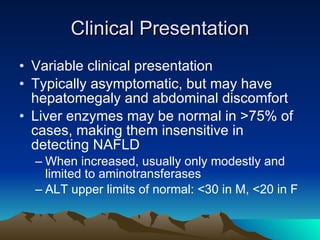

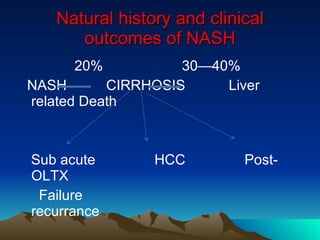

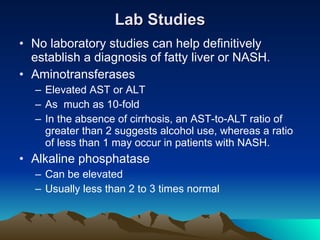

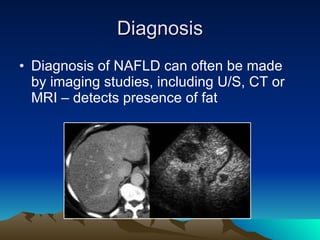

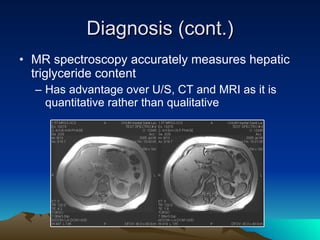

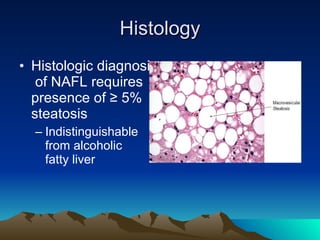

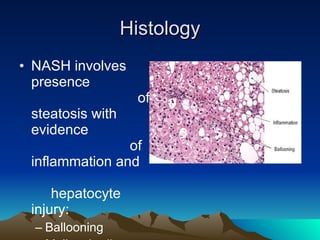

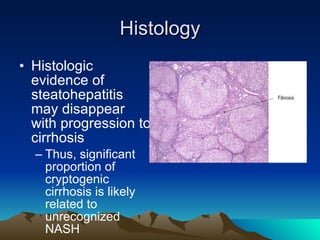

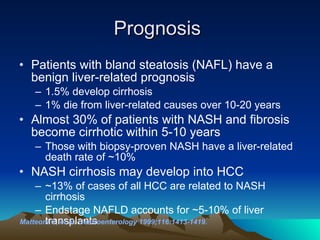

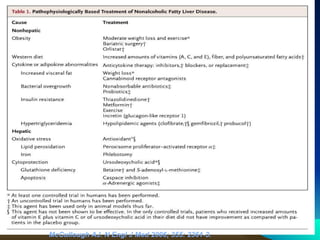

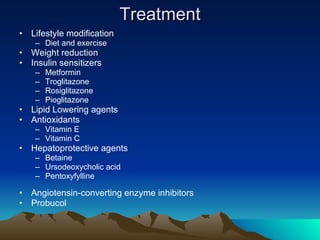

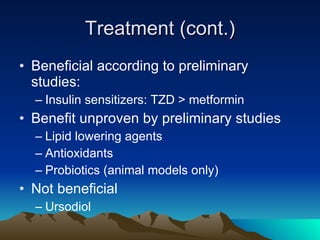

The document discusses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which includes a spectrum of conditions from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis. NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. The prevalence of NAFLD is increasing globally and varies from 5-30% in different regions. Diagnosis requires imaging and liver biopsy. Treatment focuses on lifestyle modifications and medications to improve insulin resistance.