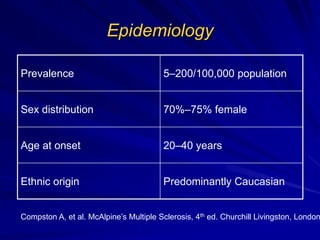

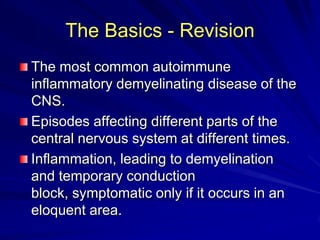

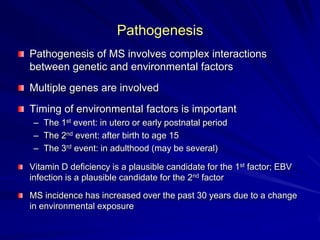

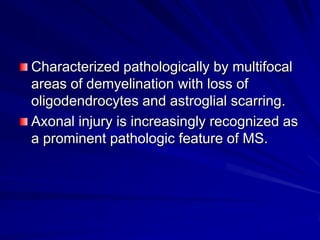

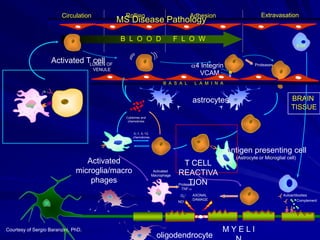

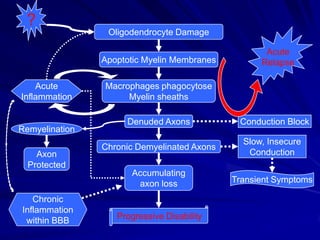

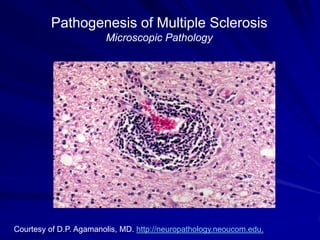

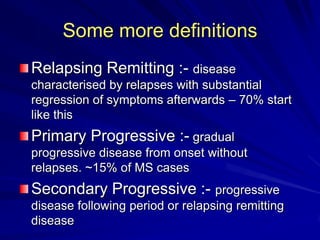

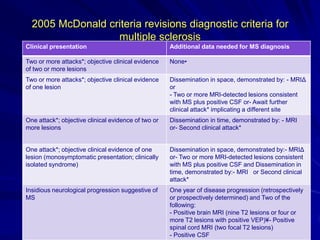

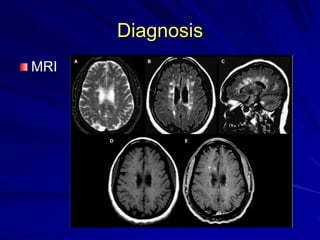

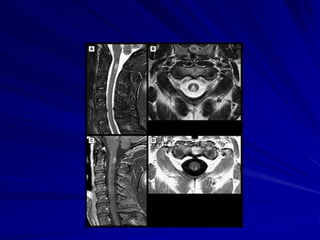

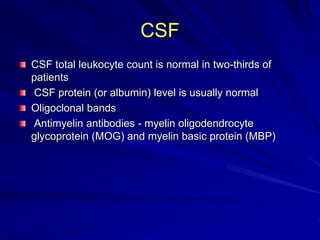

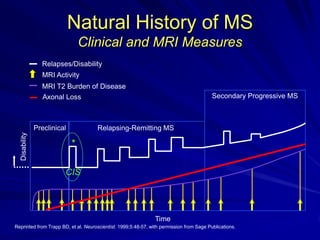

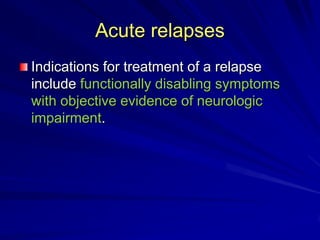

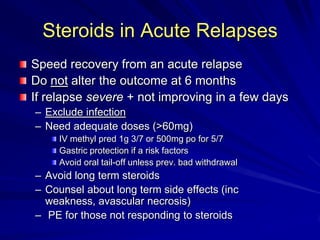

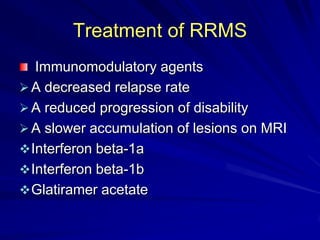

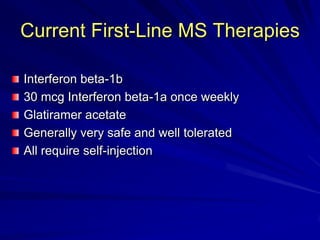

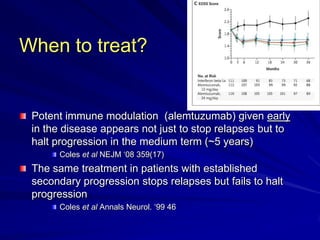

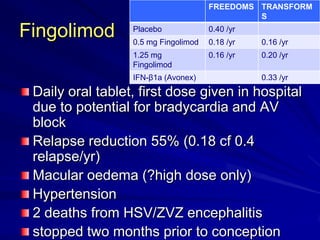

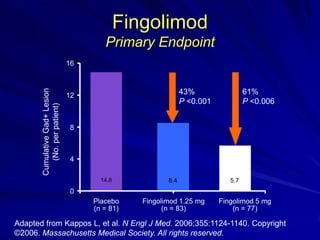

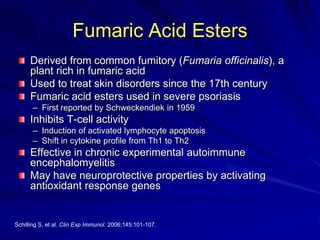

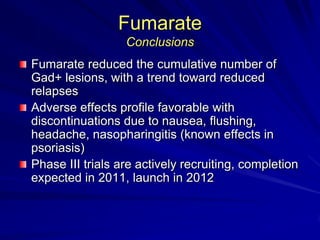

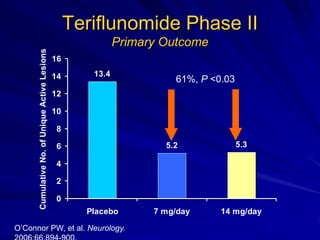

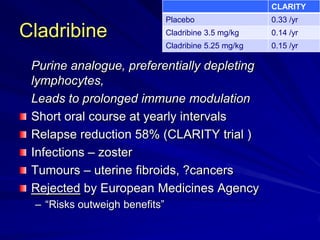

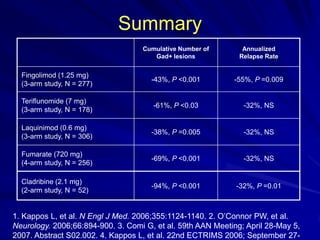

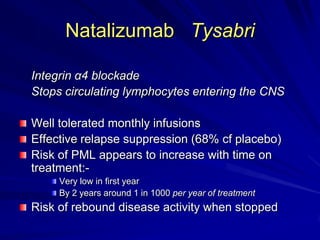

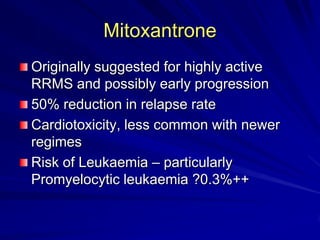

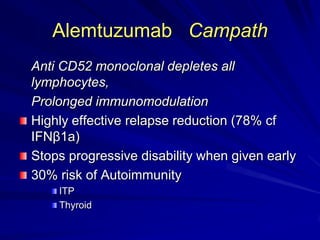

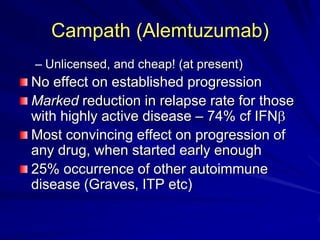

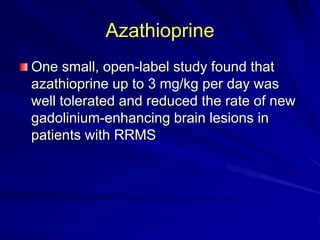

This document provides information on multiple sclerosis (MS), including its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment options. It summarizes that MS is the most common autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system characterized by inflammation and demyelination in the brain and spinal cord. Current first-line treatments for relapsing-remitting MS include interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, fumarate, teriflunomide, natalizumab, mitoxantrone, and alemtuzumab, which aim to reduce relapse rates and progression of disability.