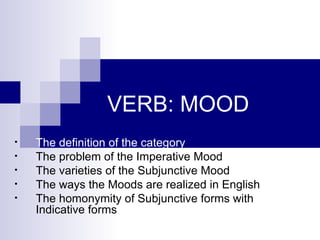

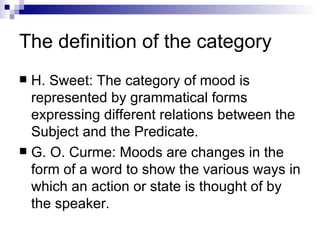

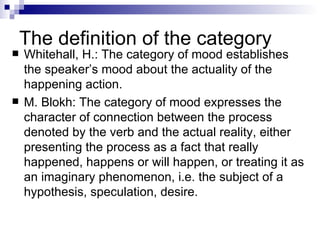

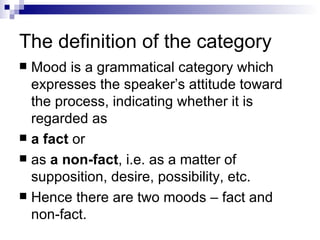

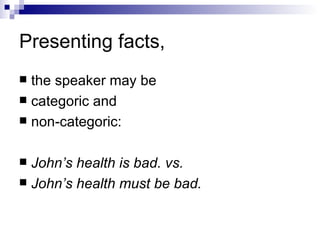

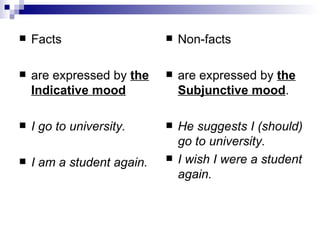

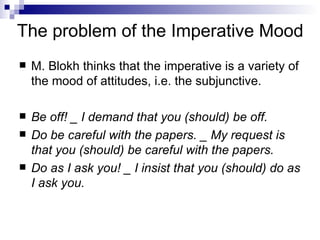

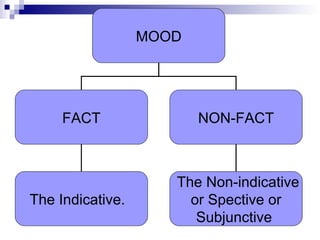

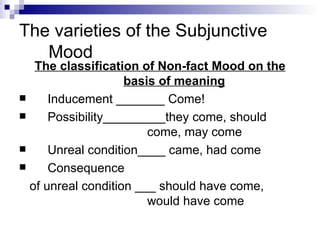

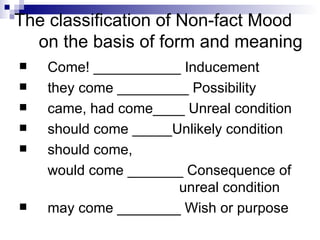

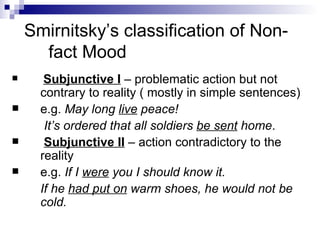

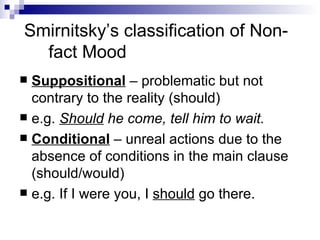

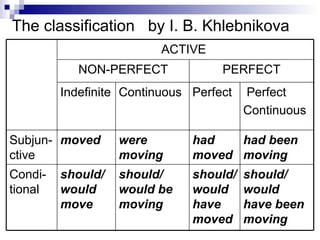

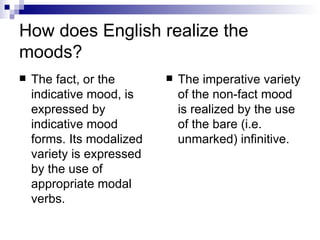

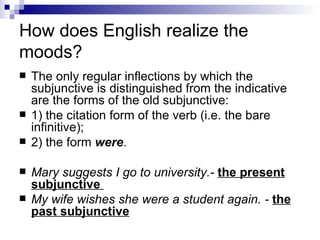

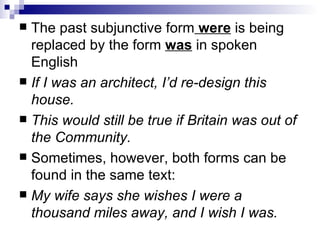

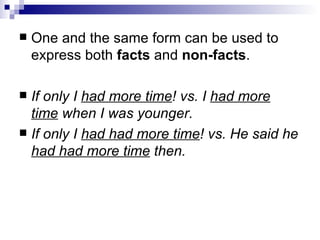

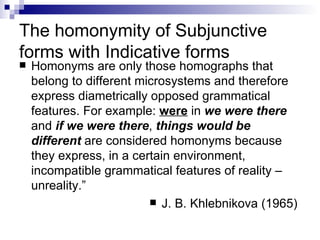

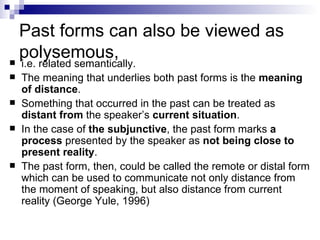

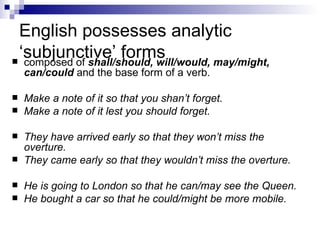

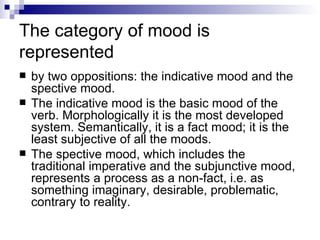

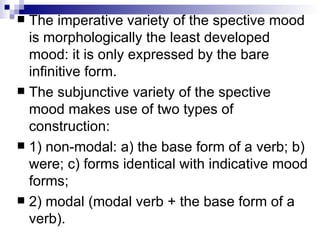

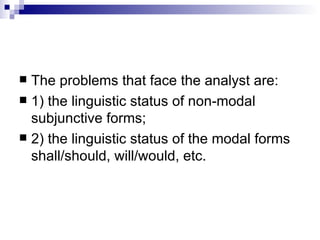

The document discusses the category of mood in the English verb. It defines mood as a grammatical category that expresses the speaker's attitude toward the process or action, indicating whether it is regarded as a fact or non-fact. The indicative mood expresses facts, while the subjunctive and imperative moods express non-facts. The subjunctive mood can be further divided into varieties based on meaning and form. The document also discusses how moods are realized in English and some issues surrounding their analysis.