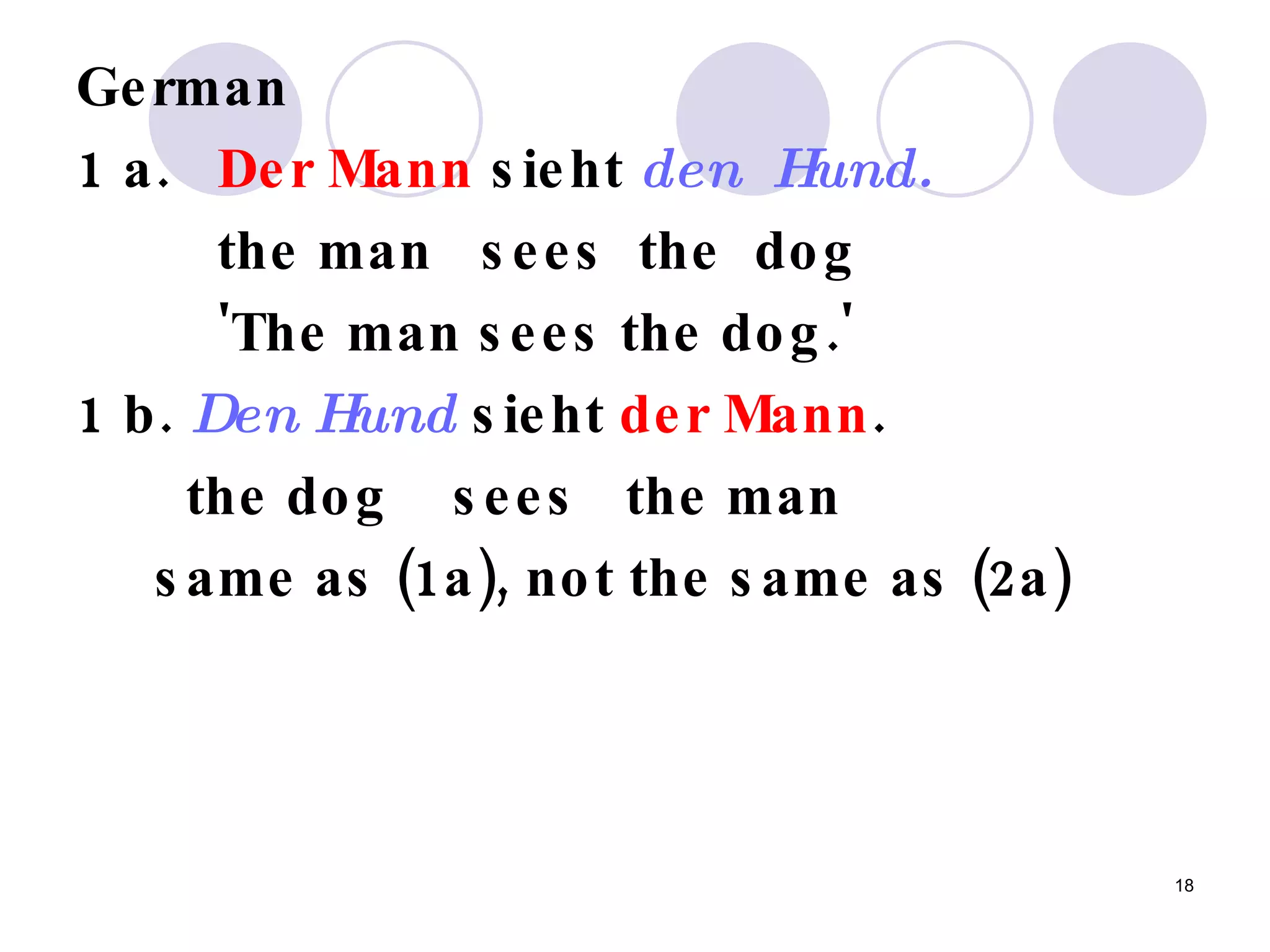

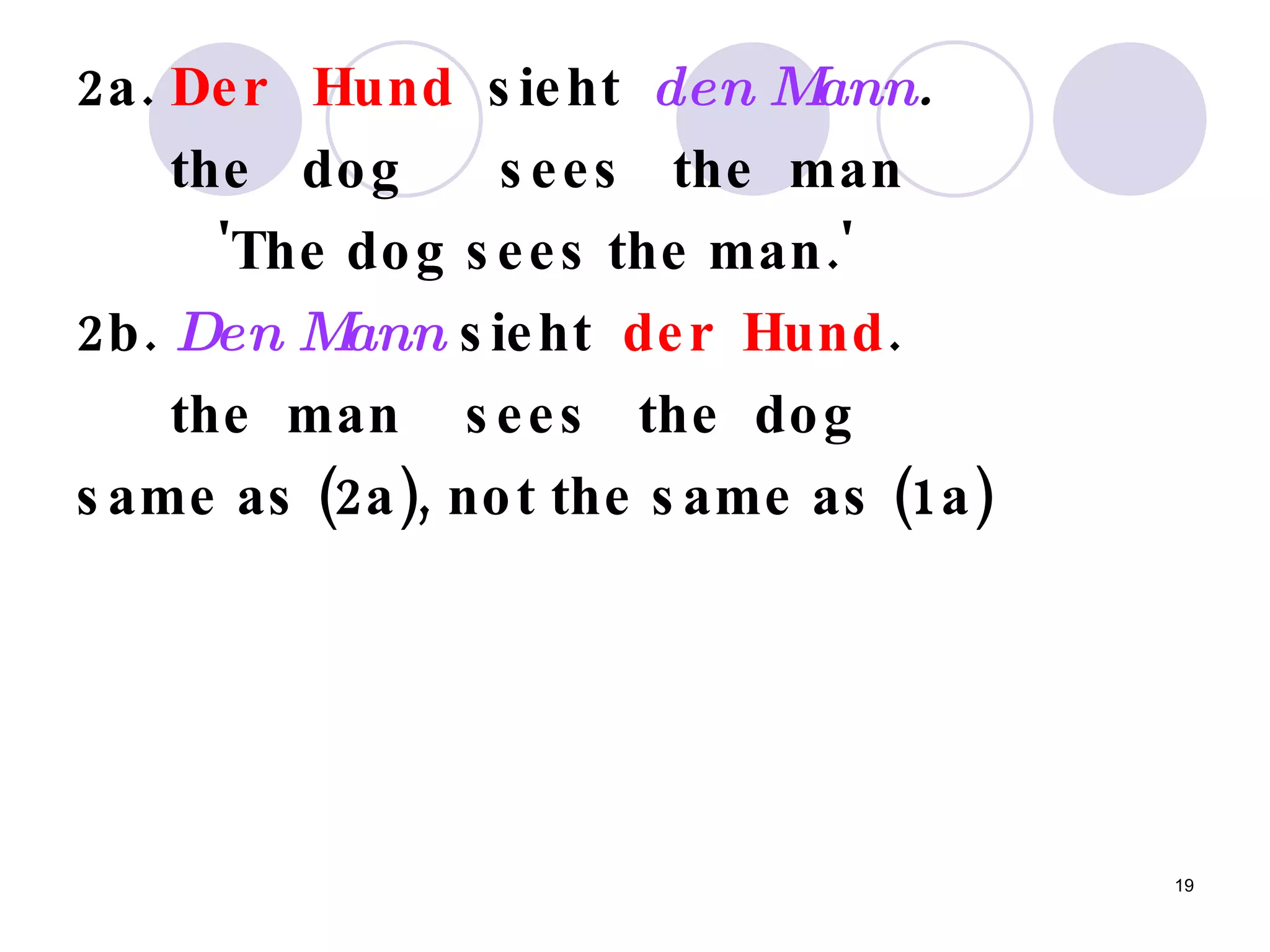

Cases express the grammatical function of nouns and pronouns in languages like Latin, German, and Finnish through inflectional endings. While modern English has lost most cases except in pronouns like "who" and "whom", other languages use cases like nominative, accusative, dative, and others to distinguish subjects, objects, and possessors based on their role in a clause. Cases help identify grammatical relations when word order is flexible, as in German sentences where subjects can precede or follow verbs.