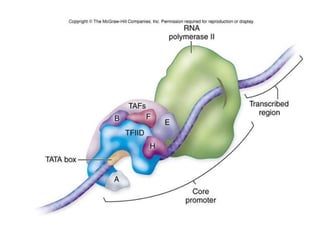

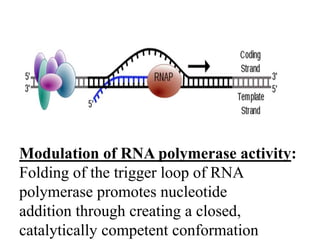

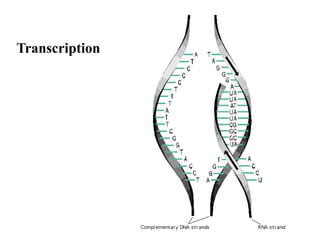

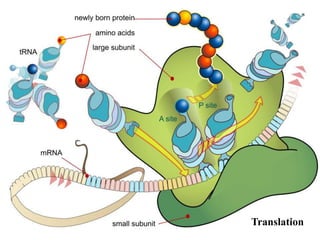

RNA polymerase is the enzyme that controls transcription by unwinding DNA, building an RNA strand based on the DNA template, and proofreading as it adds nucleotides to improve accuracy. It makes an error about once per 10,000 nucleotides. Gene expression involves two main phases - transcription of DNA into mRNA and translation of mRNA into protein by ribosomes. Regulation of gene expression modulates these processes to control when genes are expressed. Post-translational modifications further process proteins after translation through additions like phosphorylation, glycosylation and lipidation that influence protein structure and function.