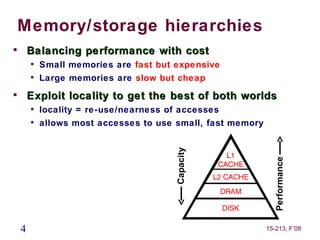

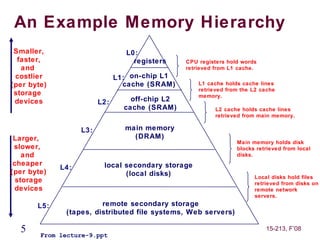

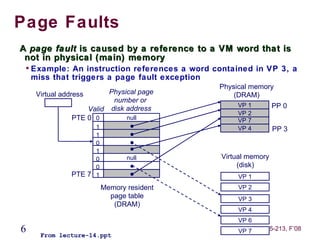

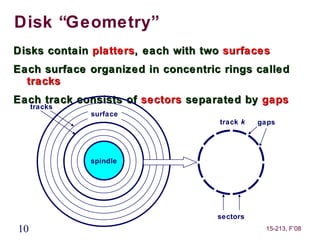

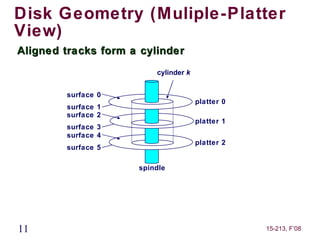

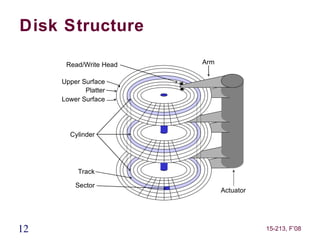

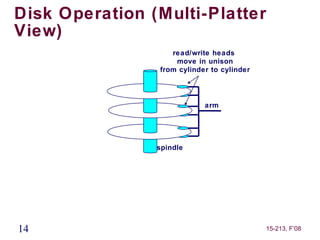

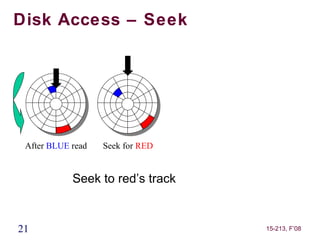

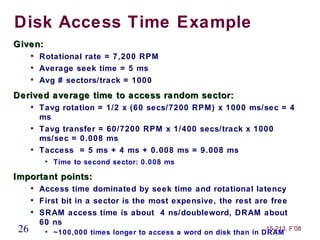

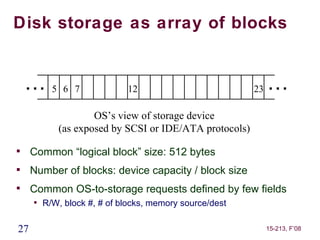

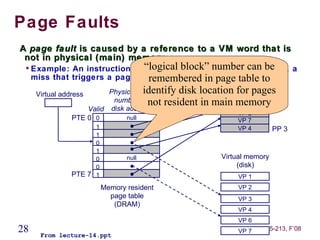

The document discusses disk-based storage technologies and how they fit within the memory hierarchy. It describes the components of a disk drive, including platters, read/write heads, actuators, and electronics. Details are provided on disk geometry, with tracks divided into sectors, and the steps involved in disk access, including seek time, rotational latency, and data transfer time.