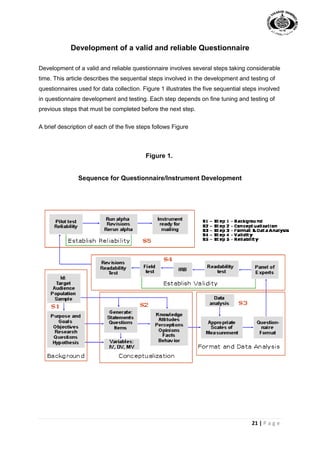

The document discusses validity and reliability of measuring instruments. It defines key terms like measurement, instruments, reliability and validity. There are different types of reliability including test-retest, parallel forms, inter-rater and internal consistency reliability. Validity refers to how well a test measures what it aims to measure. There are different types of validity like face validity and construct validity. Developing valid and reliable questionnaires involves assessing validity and reliability, considering different approaches to validity, and developing questionnaires through various steps.