Respiratory failure is a syndrome characterized by the inability of the respiratory system to adequately exchange gases, classified into hypoxemic (Type I) and hypercapnic (Type II) forms. Common causes include acute lung diseases and underlying conditions affecting the central nervous system, respiratory muscles, and airways. Effective management involves identifying and treating the underlying cause, with severe cases often requiring mechanical ventilation and intensive care support.

![ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS

SYNDROME(ARDS)

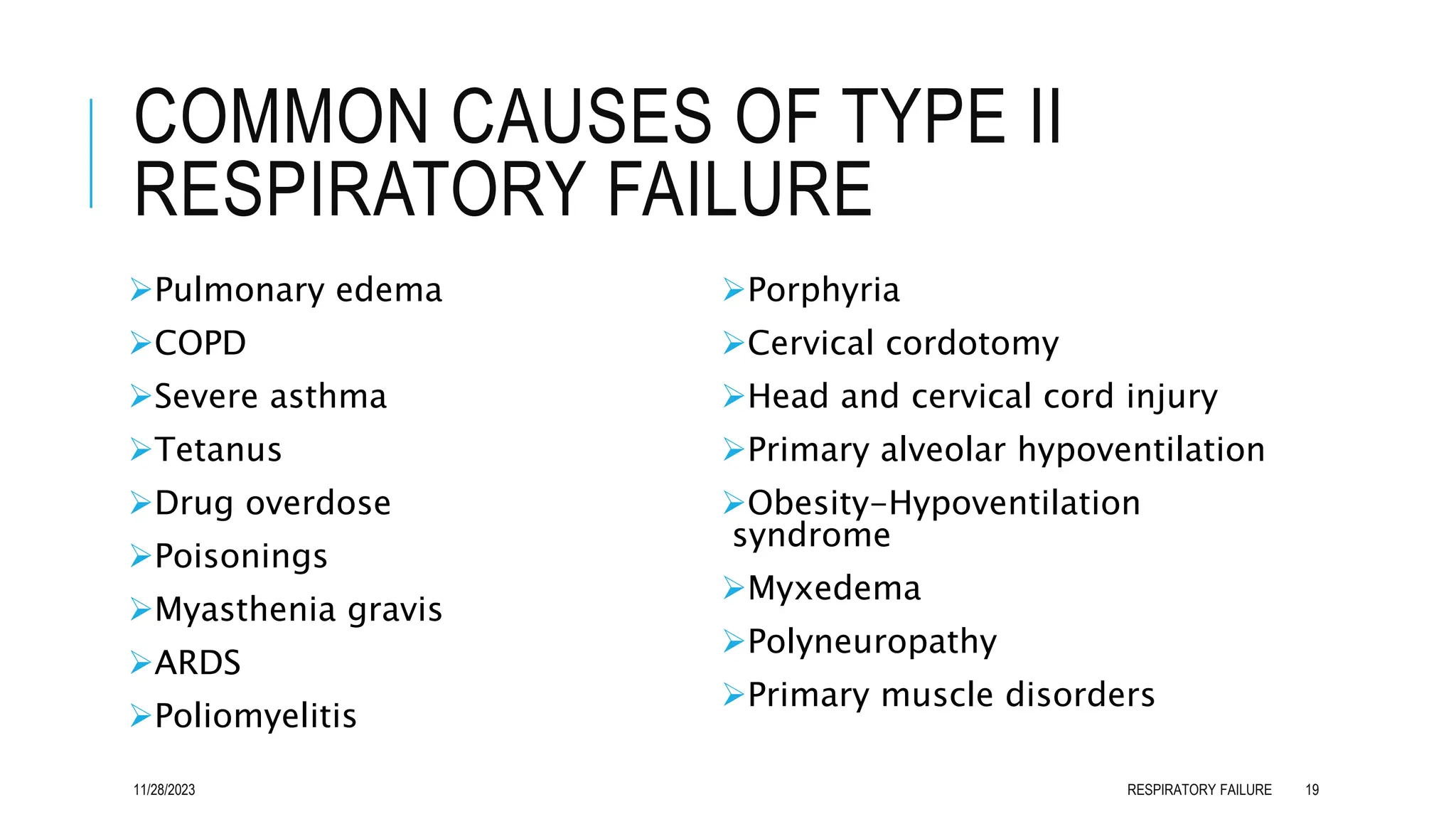

Criteria for the diagnosis of ARDS include the following:

Clinical presentation - Tachypnea and dyspnea; crackles upon auscultation

Clinical setting - Direct insult (aspiration) or systemic process causing lung

injury (sepsis)

Radiologic appearance - 3-quadrant or 4-quadrant alveolar flooding

Lung mechanics - Diminished compliance (< 40 mL/cm water)

Gas exchange - Severe hypoxia refractory to oxygen therapy (ratio of arterial

oxygen tension to fractional concentration of oxygen in inspired gas

[PaO2/FiO2] < 200)

Normal pulmonary vascular properties - Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

lower than 18 mm Hg

11/28/2023 RESPIRATORY FAILURE 23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/respiratoryfailure-kdamuda-231128090440-4814d091/75/MANAGEMENT-OF-RESPIRATORY-FAILURE-23-2048.jpg)

![REFERENCES

IJ Clifton, DAB Ellames, Respiratory Failure in Davidson’s principle and practice of Medicine 24th Ed., Chapt. 17, pp.

483-485

Vincent SM, Eman S, Abdulghani S, Bracken B: Respiratory Failure, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Jan

2023 accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526127/

Ata Murat Kaynar, Respiratory Failure, Medscape@emedicine.com

Khan NA, Palepu A, Norena M, et al. Differences in hospital mortality among critically ill patients of Asian, Native

Indian, and European descent. Chest. 2008 Dec. 134(6):1217-22.

Moss M, Mannino DM. Race and gender differences in acute respiratory distress syndrome deaths in the United

States: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data (1979- 1996). Crit Care Med. 2002 Aug. 30(8):1679-85.

Guideline] Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, Hess D, Hill NS, Nava S, et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice

guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017 Aug. 50 (2)

[Guideline] Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of

Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Available at https://www.esicm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SSC-COVID19-GUIDELINES.pdf.2020;

11/28/2023 RESPIRATORY FAILURE 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/respiratoryfailure-kdamuda-231128090440-4814d091/75/MANAGEMENT-OF-RESPIRATORY-FAILURE-35-2048.jpg)