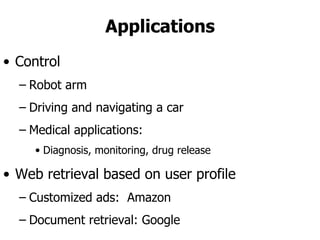

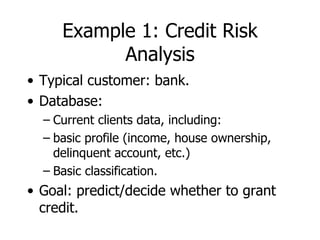

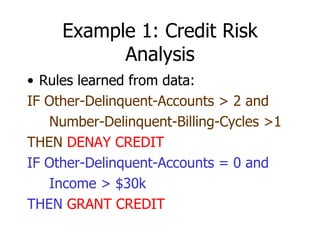

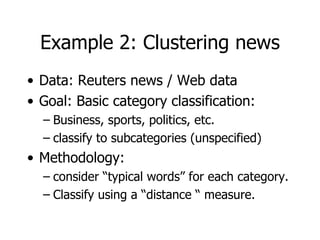

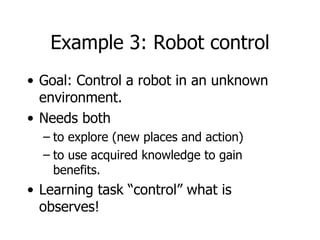

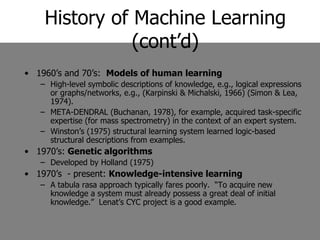

This machine learning foundations course will consist of 4 homework assignments, both theoretical and programming problems in Matlab. There will be a final exam. Students will work in groups of 2-3 to take notes during classes in LaTeX format. These class notes will contribute 30% to the overall grade. The course will cover basic machine learning concepts like storage and retrieval, learning rules, estimating flexible models, and applications in areas like control, medical diagnosis, and document retrieval.

![Predictions and Loss Model quadratic loss Predict a “real number” q for outcome 1. Loss (q-p) 2 for outcome 1 Loss ([1-q]-[1-p]) 2 for outcome 0 Expected loss: (p-q) 2 Minimized for p=q (Optimal prediction) recovers the probabilities Needs to know p to compute loss!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/machine-learning-foundations-course-number-03684034014333/85/Machine-Learning-Foundations-Course-Number-0368403401-26-320.jpg)

![The basic PAC Model Unknown target function f(x) Distribution D over domain X Goal: find h(x) such that h(x) approx. f(x) Given H find h H that minimizes Pr D [h(x) f(x)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/machine-learning-foundations-course-number-03684034014333/85/Machine-Learning-Foundations-Course-Number-0368403401-28-320.jpg)

![Basic PAC Notions S - sample of m examples drawn i.i.d using D True error (h)= Pr D [h(x)=f(x)] Observed error ’(h)= 1/m |{ x S | h(x) f(x) }| Example (x,f(x)) Basic question: How close is (h) to ’(h)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/machine-learning-foundations-course-number-03684034014333/85/Machine-Learning-Foundations-Course-Number-0368403401-29-320.jpg)

![Bayesian Theory Prior distribution over H Given a sample S compute a posterior distribution: Maximum Likelihood (ML) Pr[S|h] Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) Pr[h|S] Bayesian Predictor h(x) Pr[h|S] .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/machine-learning-foundations-course-number-03684034014333/85/Machine-Learning-Foundations-Course-Number-0368403401-30-320.jpg)