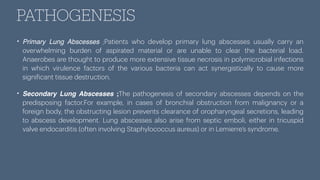

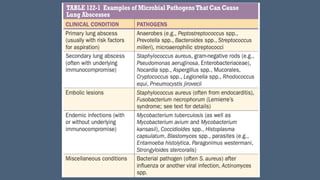

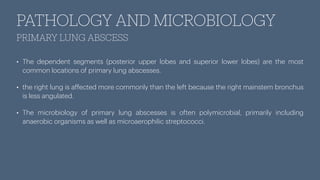

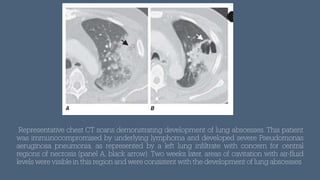

Lung abscesses result from microbial infection leading to lung tissue necrosis and are categorized as primary (80% of cases) or secondary; the former from aspiration and the latter associated with existing health conditions. The condition primarily affects middle-aged men and is linked to aspiration risks, with clinical presentations resembling pneumonia but may include foul-smelling sputum in anaerobic cases. Diagnosis involves imaging and culture, while treatment often includes clindamycin, with complications ranging from recurrence to life-threatening conditions and the need for surgical intervention in severe cases.