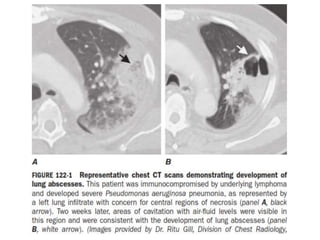

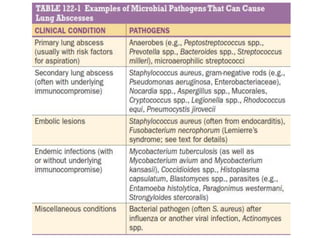

Lung abscesses are cavitary lung lesions caused by microbial infection. They can be primary, arising from aspiration of oral bacteria, or secondary, caused by an underlying condition impairing lung defenses. Primary abscesses are often polymicrobial and anaerobic, located in dependent lung regions. Secondary abscesses involve a broader range of pathogens depending on the host's condition. Symptoms may resemble pneumonia initially but become more chronic. Imaging identifies cavitary lesions while microbiological testing guides targeted antibiotic therapy, sometimes with drainage for large abscesses.