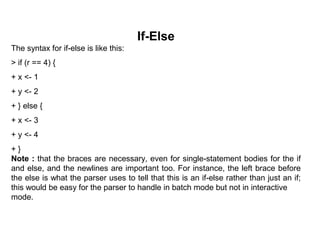

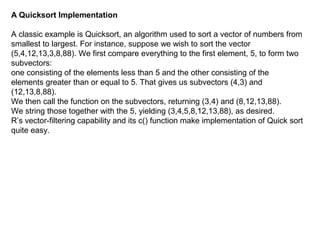

This document discusses basic loops and functions in R programming. It covers control statements like loops and if/else, arithmetic and boolean operators, default argument values, and returning values from functions. It also describes R programming structures, recursion, and provides an example of implementing quicksort recursively and constructing a binary search tree. The key topics are loops, control flow, functions, recursion, and examples of sorting and binary trees.

![Control Statements

Loops

Basic Structure

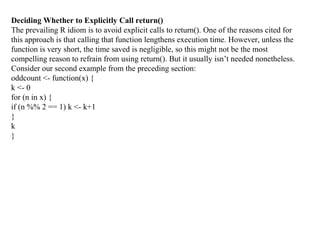

In our function oddcount() the line

for (n in x) {

will be instantly recognized by Python programmers. It of course means that

there will be one iteration of

the loop for each component of the vector x, with n taking on the values of those

components.

In otherwords, in the first iteration, n = x[1], in the second iteration n = x[2], etc.

For example:

> x <- c(5,12,13)

> for (n in x) print(nˆ2)

[1] 25

[1] 144

[1] 169

C-style looping with while and repeat are also available, complete with break:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-4-320.jpg)

![> i <- 1

> while(1) {

+ i <- i+4

+ if (i > 10) break

+ }

> i

[1] 13

Of course, break can be used with for too.

Another useful statement is next, which instructs the interpreter to go to the next

iteration of the loop.

Usage of this construct often allows one to avoid using complexly nested if-then-

else statements, which make the

code confusing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-5-320.jpg)

![Looping Over Nonvector Sets

The for construct works on any vector, regardless of mode. One can loop over a

vector of file names, for

instance. Say we have files x and y with contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

and

5

12

13

Then this loop prints each of them:

> for (fn in c("x","y")) print(scan(fn))

Read 6 items

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6

Read 3 items

[1] 5 12 13

R does not directly support iteration over nonvector sets, but there are indirect

yet easy ways to accomplish

it. One way would be to use lapply()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-6-320.jpg)

![get(), as in the

following example. Here we have two matrices, u and v, containing statistical data,

and we wish to apply R

linear regression function lm() to each of them:

> u

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 1 1

[2,] 2 2

[3,] 3 4

> v

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 8 15

[2,] 12 10

[3,] 20 2

> for (m in c("u","v")) {

+ z <- get(m)

+ print(lm(z[,2] ˜ z[,1]))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-7-320.jpg)

![Call:

lm(formula = z[, 2] ˜ z[, 1])

Coefficients:

(Intercept) z[, 1]

-0.6667 1.5000

Call:

lm(formula = z[, 2] ˜ z[, 1])

Coefficients:

(Intercept) z[, 1]

23.286 -1.071

The reader is welcome to make his/her own refinements here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-8-320.jpg)

![These values change to 1 and 0 in arithmetic expressions, e.g.

> 1 < 2

[1] TRUE

> (1 < 2) * (3 < 4)

[1] 1

> (1 < 2) * (3 < 4) * (5 < 1)

[1] 0

> (1 < 2) == TRUE

[1] TRUE

> (1 < 2) == 1

[1] TRUE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-11-320.jpg)

![No Pointers in R

R does not have variables corresponding to pointers or references like those of,

say, the C language. This can make programming more difficult in some cases.

(As of this writing, the current version of R has an experimental feature called

reference classes, which may reduce the difficulty.)

For example, you cannot write a function that directly changes its arguments.

>>> x = [13,5,12]

>>> x.sort()

>>> x

[5, 12, 13]

Here, the value of x, the argument to sort(), changed. By contrast, here’s

how it works in R:

> x <- c(13,5,12)

> sort(x)

[1] 5 12 13

> x

[1] 13 5 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-18-320.jpg)

![qs <- function(x) {

if (length(x) <= 1) return(x)

pivot <- x[1]

therest <- x[-1]

sv1 <- therest[therest < pivot]

sv2 <- therest[therest >= pivot]

sv1 <- qs(sv1)

sv2 <- qs(sv2)

return(c(sv1,pivot,sv2))

}

if (length(x) <= 1) return(x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-21-320.jpg)

![Extended Example: A Binary Search Tree

stored 8 in the root—that is, the head—of the tree. Its two child nodes contain 5

and 20, and the former itself has two child nodes, which store 2 and 6.

> x <- newtree(8,3)

> x

$mat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] NA NA 8

[2,] NA NA NA

[3,] NA NA NA

$nxt

[1] 2

$inc

[1] 3

> x <- ins(1,x,5)

> x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-23-320.jpg)

![$mat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 NA 8

[2,] NA NA 5

[3,] NA NA NA

$nxt

[1] 3

$inc

[1] 3

> x <- ins(1,x,6)

> x

$mat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 NA 8

[2,] NA 3 5

[3,] NA NA 6

$nxt

[1] 4

$inc

[1] 3

> x <- ins(1,x,2)

> x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-24-320.jpg)

![$mat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 NA 8

[2,] 4 3 5

[3,] NA NA 6

[4,] NA NA 2

[5,] NA NA NA

[6,] NA NA NA

$nxt

[1] 5

$inc

[1] 3

> x <- ins(1,x,20)

> x

$mat

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] 2 5 8

[2,] 4 3 5

[3,] NA NA 6

[4,] NA NA 2

[5,] NA NA 20

[6,] NA NA NA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-25-320.jpg)

![$nxt

[1] 6

$inc

[1] 3

What happened here? First, the command containing our call newtree(8,3) creates

a new tree, assigned to x, storing the number 8. The argument 3 specifies that we

allocate storage room three rows at a time.

The result is that the matrix component of the list x is now as follows:

[,1] [,2] [,3]

[1,] NA NA 8

[2,] NA NA NA

[3,] NA NA NA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-26-320.jpg)

![NOTE This example is for the purpose of demonstrating recursion. R’s own sort

function,

sort(), is much faster, as it is written in C.

qs <- function(x) {

if (length(x) <= 1) return(x)

pivot <- x[1]

therest <- x[-1]

sv1 <- therest[therest < pivot]

sv2 <- therest[therest >= pivot]

sv1 <- qs(sv1)

sv2 <- qs(sv2)

return(c(sv1,pivot,sv2))

}

if (length(x) <= 1) return(x)

Without this, the function would keep calling itself repeatedly on empty vectors,

executing forever.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/loopsandfunctionsinr-181101062724/85/Loops-and-functions-in-r-28-320.jpg)