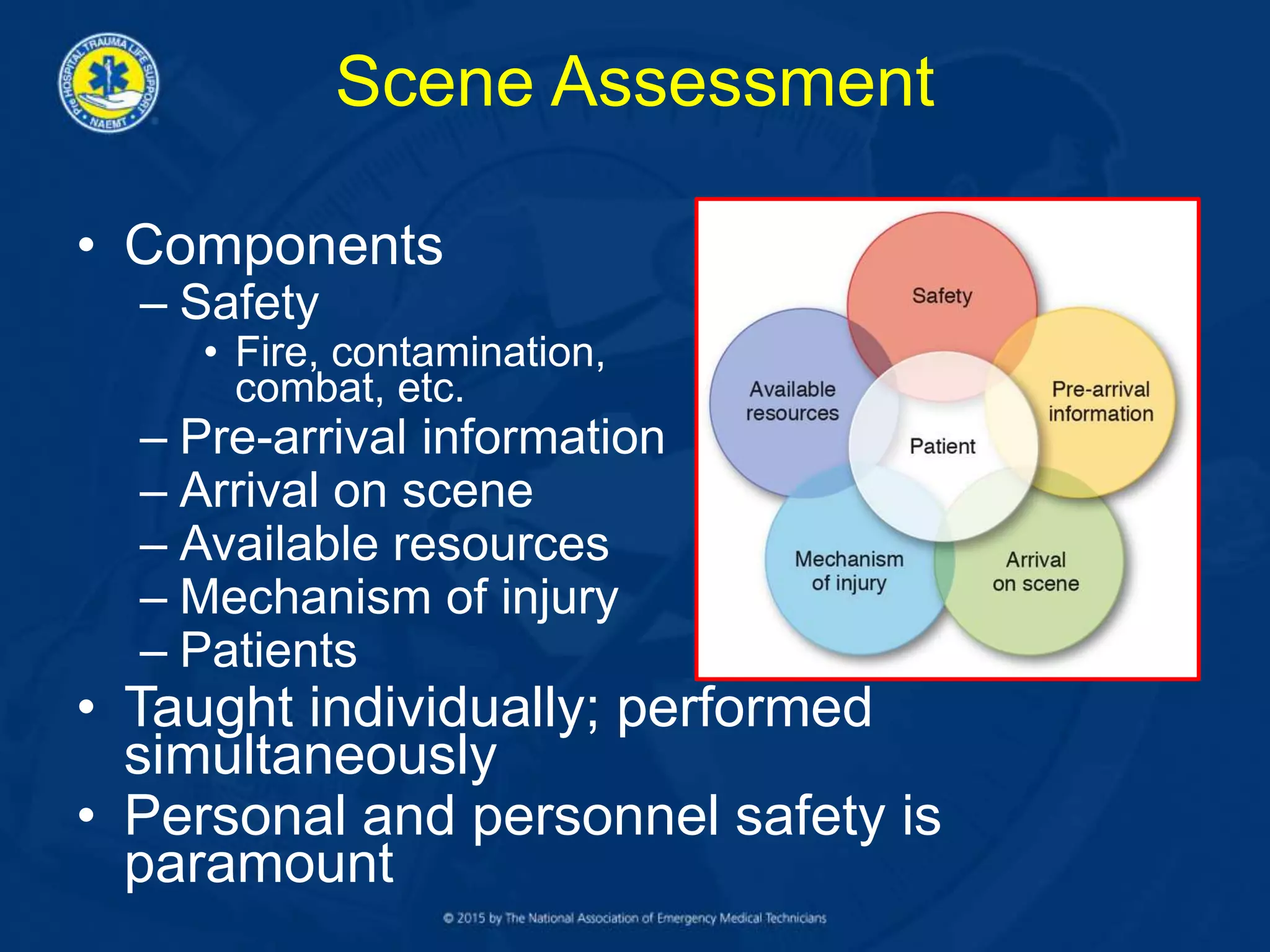

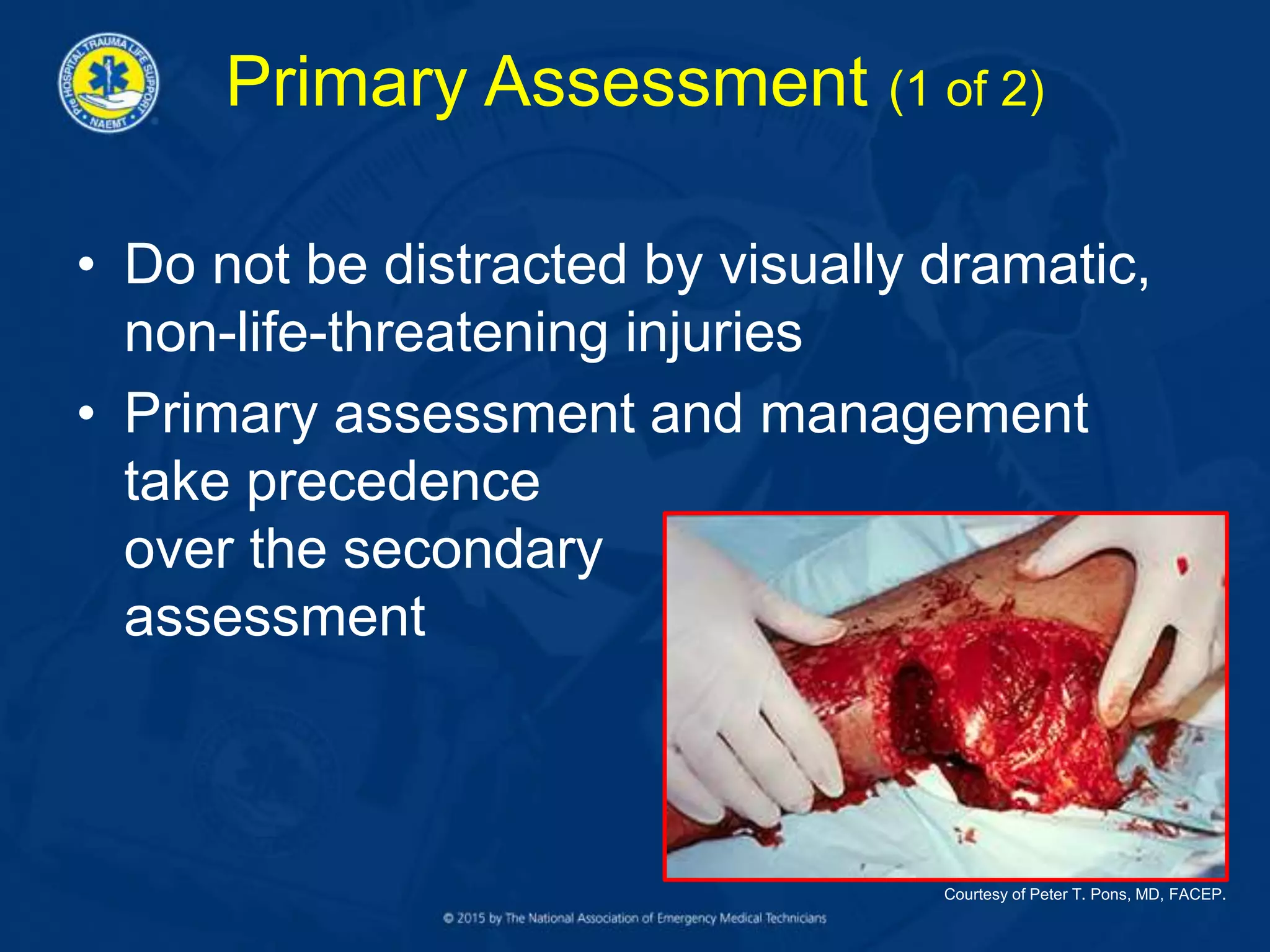

Scene assessment involves evaluating safety, pre-arrival information, arrival on scene, available resources, and mechanism of injury. The primary assessment evaluates airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and environment/exposure to identify life-threatening conditions. This assessment determines if the patient is sick, not yet sick, or not sick. Based on these assessments, the responder decides if immediate transport is needed, if further assessment is required, how to package the patient, the transport method, and receiving facility.