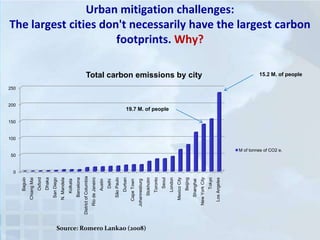

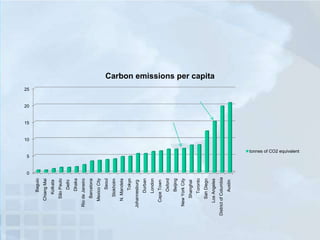

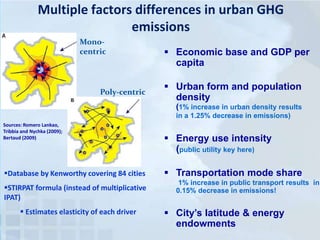

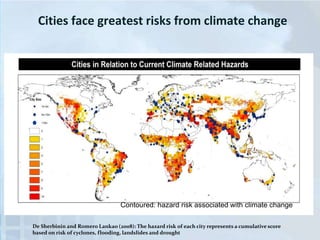

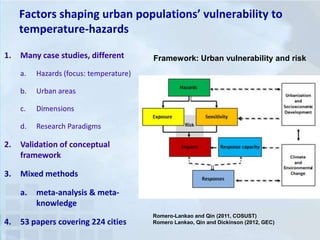

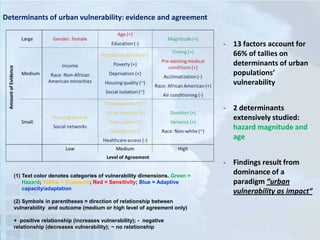

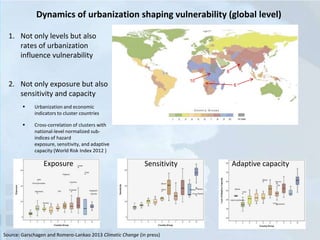

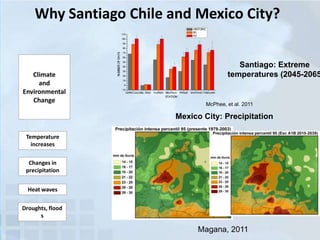

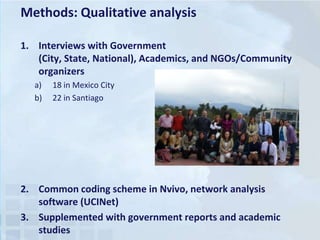

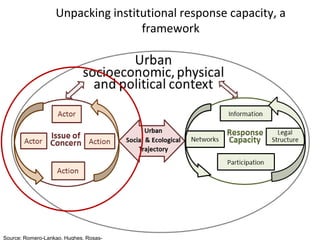

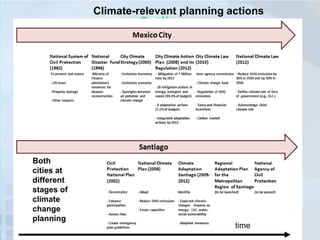

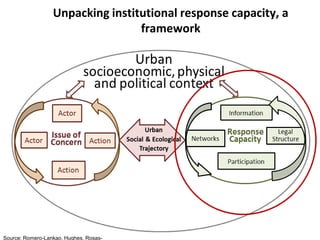

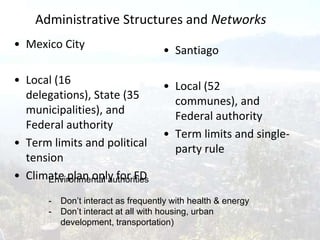

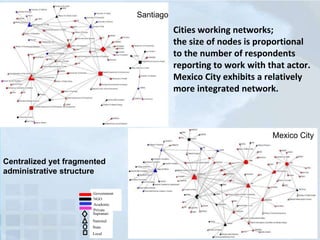

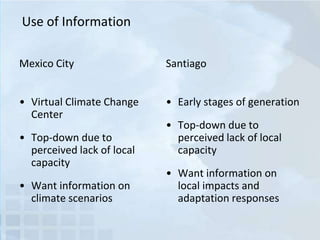

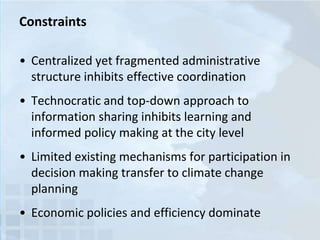

This document discusses enhancing cities' roles in transitioning to sustainability and resilience. It examines the dynamics of urbanization that influence urban emissions, vulnerability and risk. It also looks at cities' institutional capacity to reduce emissions while improving resilience. The document analyzes total and per capita carbon emissions for various cities, finding the largest cities don't always have the largest footprints due to factors like urban form, population density, transportation modes and energy use intensity. It also discusses how cities face different risks from climate change impacts. Finally, the document examines institutional response capacity for climate change in Mexico City and Santiago, Chile, finding they have different administrative structures, use of information, participation mechanisms, opportunities and constraints.