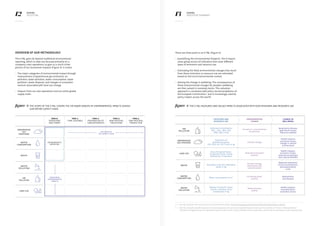

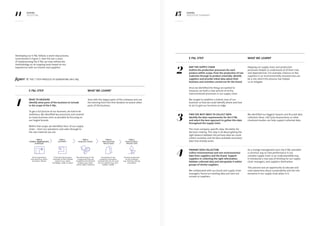

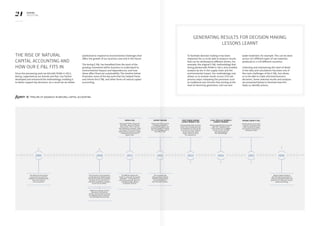

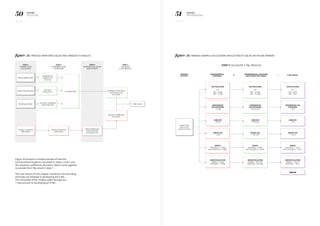

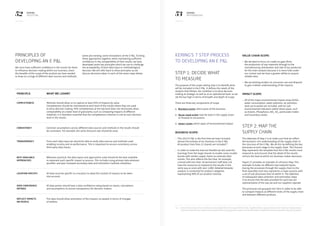

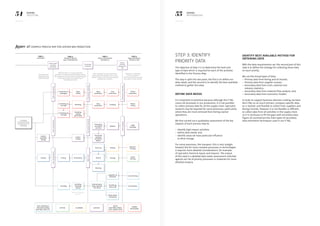

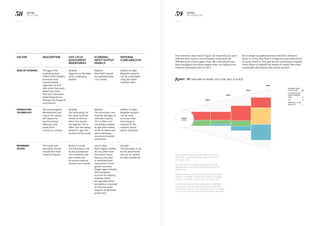

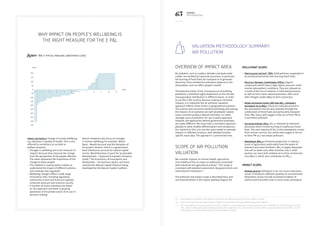

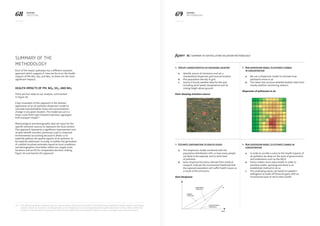

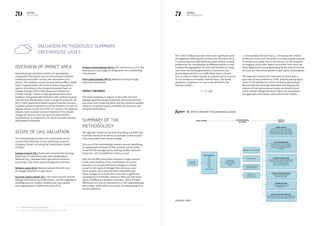

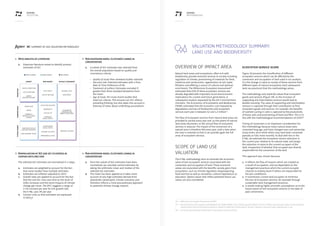

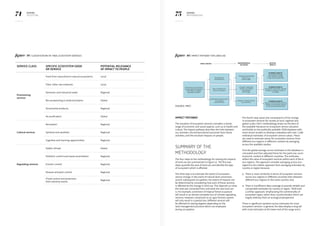

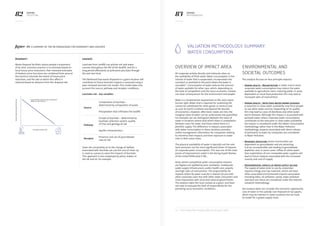

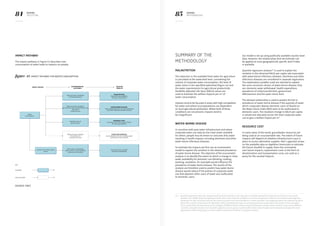

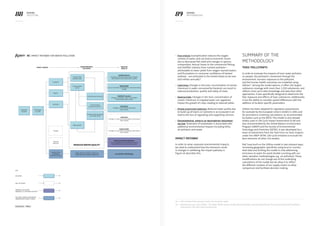

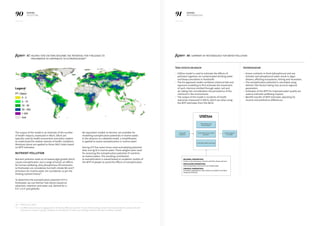

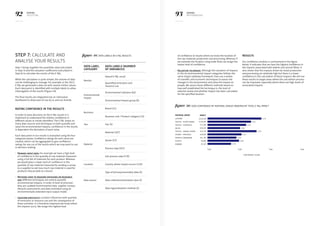

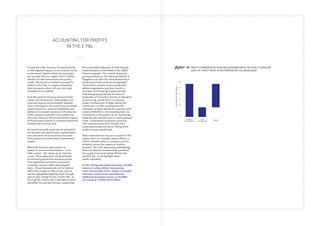

Kering developed the Environmental Profit and Loss account (e P&L) to measure its environmental footprint across its brands' supply chains, highlighting impacts on natural capital and driving sustainable business practices. By quantifying environmental costs in monetary terms, Kering aims to inform decision-making and foster innovation while sharing its methodology to promote corporate natural capital accounting. The e P&L underscores the importance of integrating environmental considerations into business strategies to mitigate risks and enhance sustainability.