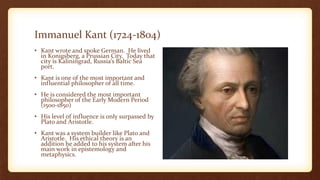

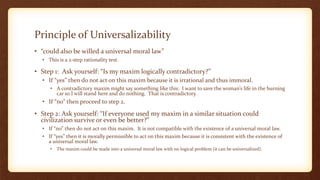

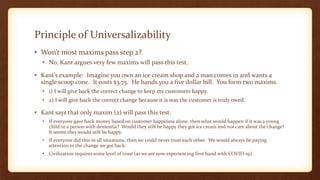

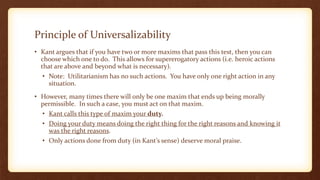

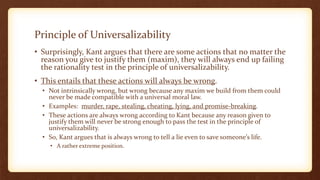

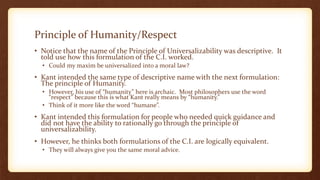

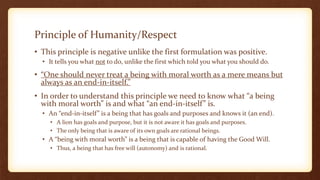

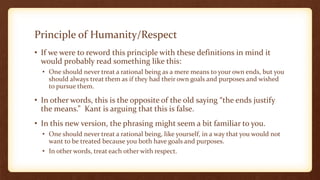

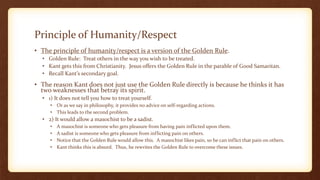

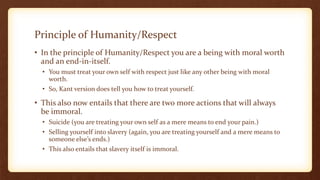

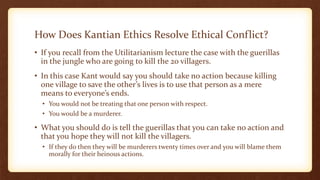

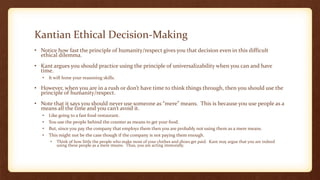

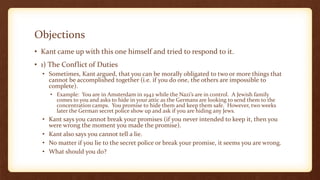

Kantian ethics, founded by Immanuel Kant, is a deontological ethical theory emphasizing duty over consequences and aimed at creating a fully rational moral framework. Central to Kant's ethics are the concepts of the good will, categorical imperative, and the principles of universalizability and humanity, which guide moral decision-making and the treatment of rational beings. Kant argues that ethical actions must respect individuals as ends-in-themselves, and any action that cannot be universalized or treats beings merely as means is inherently immoral.