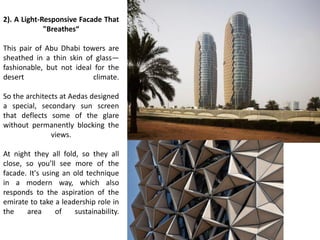

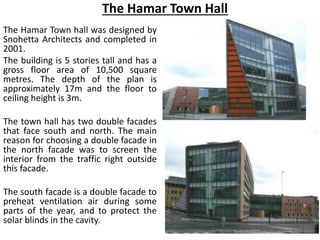

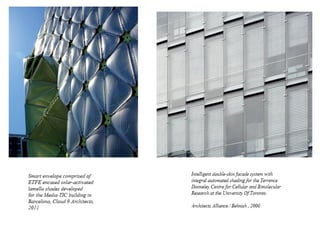

The document discusses intelligent building envelopes as environmental filters that adapt to outdoor conditions, particularly in hot arid climates. It highlights various innovative facade technologies such as energy-producing algae walls, light-responsive facades, and air-purifying materials, emphasizing their importance for occupant well-being and energy efficiency in modern architecture. The summary includes examples of notable buildings employing these intelligent strategies to address energy consumption and improve comfort.