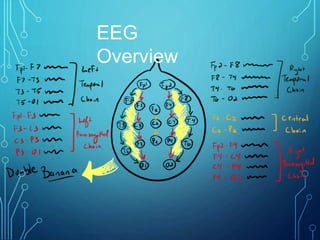

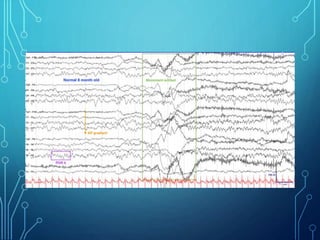

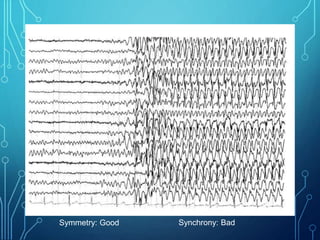

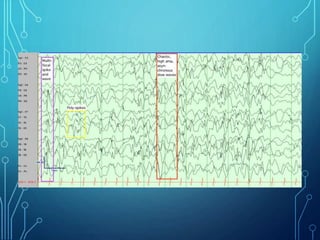

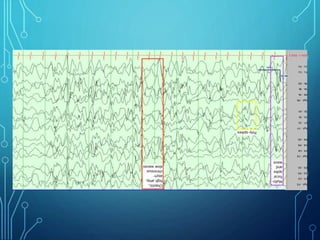

- Infantile spasms, also known as West syndrome, is a specific type of epilepsy seen in infants characterized by infantile spasms, hypsarrhythmia on EEG, and developmental regression or delay.

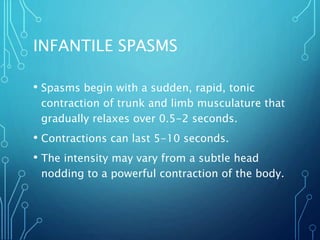

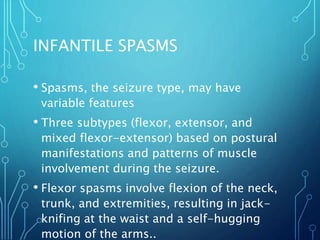

- It represents 2% of epilepsies and typically presents between 4-6 months of age. The condition was first described in 1841 and involves sudden flexion or extension of the trunk and limbs.

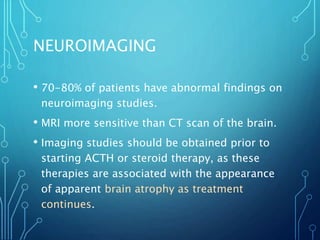

- Evaluation involves neurological exam, imaging (often MRI), metabolic testing, and characteristic EEG findings of hypsarrhythmia. Treatment aims to stop spasms and normalize EEG typically within 2-4 weeks using ACTH/steroids as first line. Prognosis depends on

![TREATMENT

• First-line treatments (ie, ACTH, prednisone,

vigabatrin, pyridoxine [vitamin B-6])

• USA natural, porcine ACTH (ACTHAR) -- $$$$$$

• Europe tetracosactide, synthetic -- $

• Second-line treatments (ie, benzodiazepines,

valproic acid, lamotrigine, topiramate,

zonisamide)

• Combo?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/infantilespasms-creed-231024212150-ef34837a/85/Infantile-Spasms-ppt-44-320.jpg)