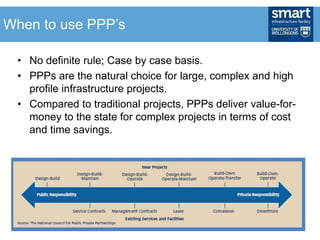

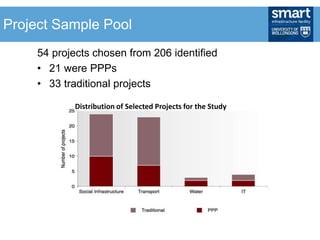

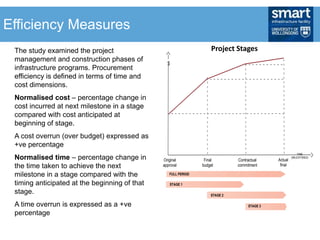

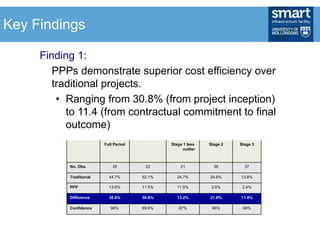

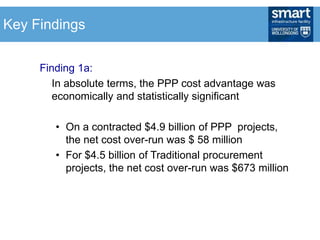

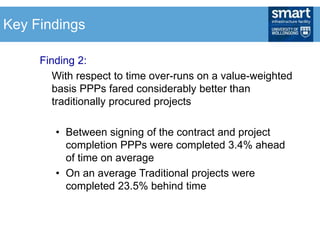

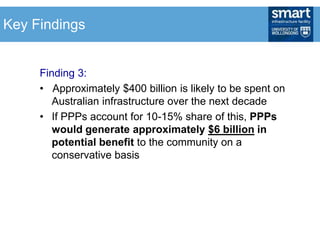

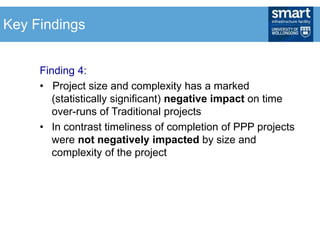

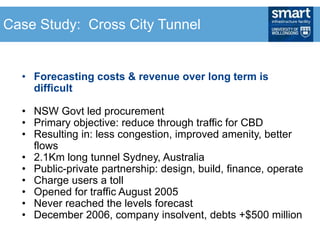

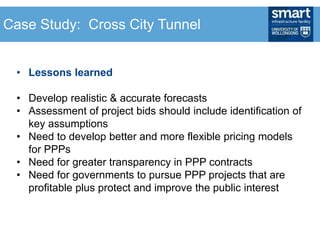

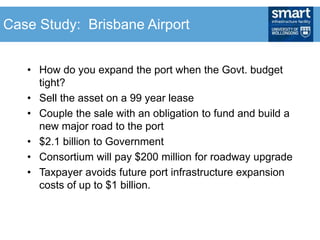

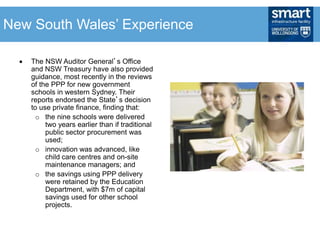

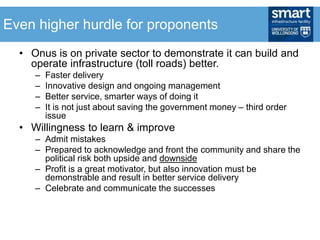

The document discusses Australia's experience with public-private partnerships (PPPs) in infrastructure. It finds that PPPs have led to more cost-efficient projects compared to traditionally procured projects, with cost overruns 30-11% lower. PPPs also saw fewer time overruns, completing projects an average of 3.4% ahead of schedule compared to 23.5% behind for traditional projects. Case studies of specific PPP transport projects show they were delivered on time and on budget, providing benefits to the community, while highlighting lessons learned around realistic forecasting and ensuring public interest is protected.