Raising the efficiency of educational services

The document discusses raising the efficiency of educational services through three main points:

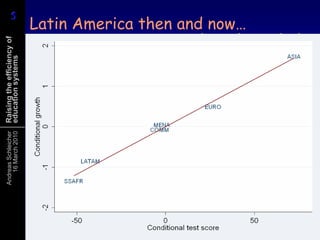

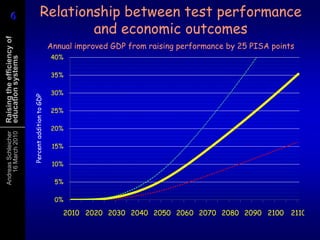

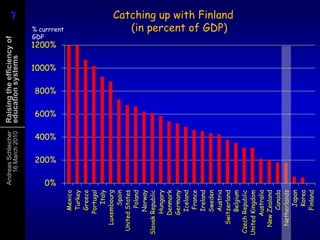

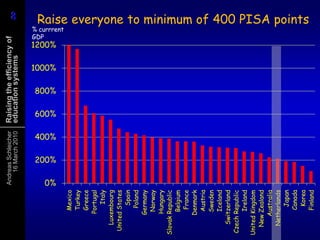

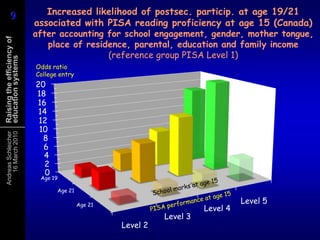

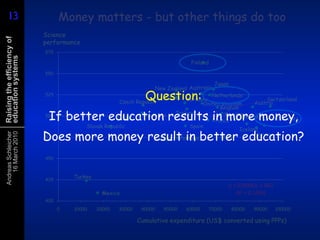

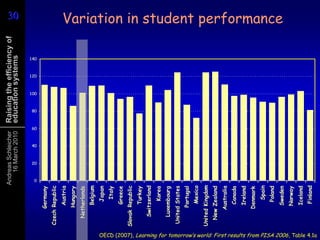

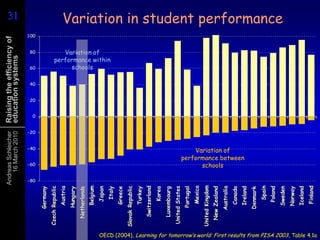

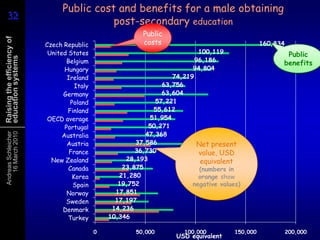

1) Improving student performance and linking higher performance to greater economic outcomes. Even modest improvements could have large economic benefits.

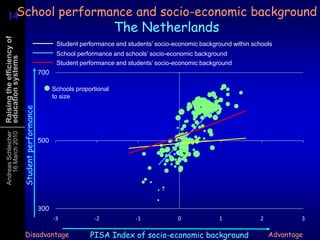

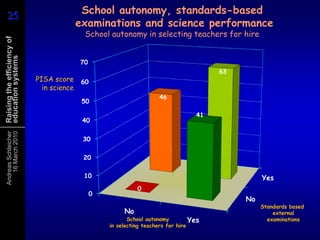

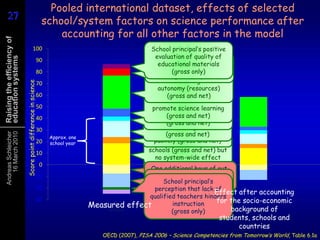

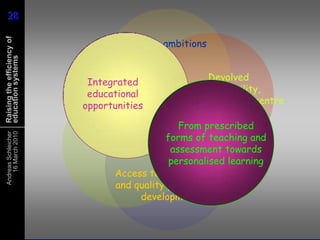

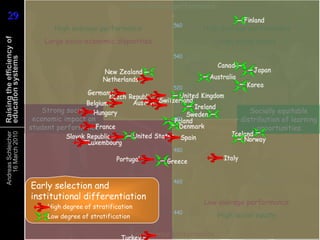

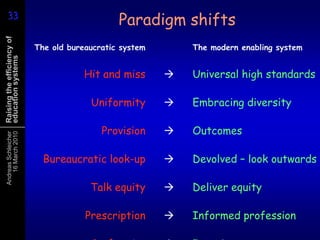

2) International examples show that greater school autonomy, use of standards, and focus on science learning are associated with higher performance.

3) Successful systems also attract and retain great teachers, have high expectations for all students, and provide access to best practices and professional development.