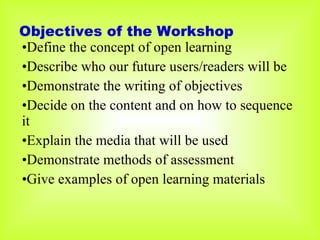

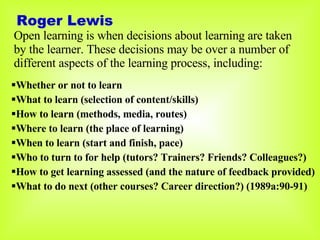

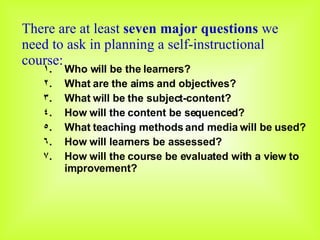

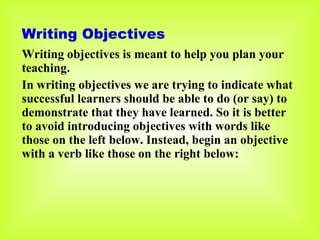

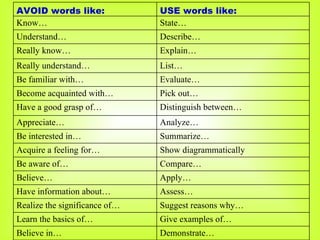

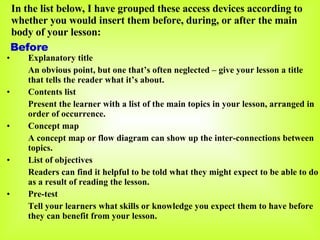

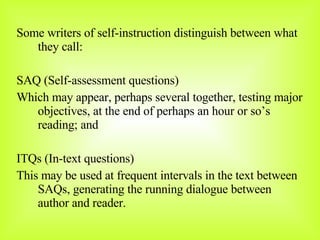

The document provides guidance on developing open learning materials. It defines open learning as enabling self-directed learning where the learner has control over various aspects of the learning process. It recommends asking seven questions when planning a self-instructional course, including the learners, objectives, content, sequencing, teaching methods, assessment, and evaluation. Tips are provided on writing objectives, deciding content, writing lessons, and including features before, during, and after lessons to support self-directed learning.